Fri 26 Feb 2010

HAD I BUT KNOWN AUTHORS #1: ANITA BLACKMON, by Curt J. Evans.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Pulp Fiction[6] Comments

by Curt J. Evans

In Murder for Pleasure, the essential 1941 study of the detective story as a literary form, Howard Haycraft listed ten women authors who constituted what he called the “better element”of the so-called HIBK, or Had I But Known, school of mystery fiction, which was founded by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1958) over three decades earlier with the publication of her hugely popular debut novel, The Circular Staircase (1908).

The Had I But Known school of mystery fiction, as it was so dubbed by (mostly male) mystery critics after the term was used by Ogden Nash in a satirical 1940 poem, typically included mysteries with female narrators given to digressive regrets over the things they might have done to prevent the novel’s numerous murders, had they only been able to see the dire consequences of their inaction.

Haycraft’s list of the ten premier Rinehart followers includes several names still fairly well-known to genre fans today, namely Mignon Eberhart, Leslie Ford and Dorothy Cameron Disney, but also more obscure names as well.

Three of these writers, Charlotte Murray Russell and the sisters Constance and Gwenyth Little, have recently had works reprinted and resultingly undergone some reader revival, but the remaining four, Anita Blackmon, Margaret N. Armstrong, Clarissa Fairchild Cushman and Medora Field, remain almost entirely forgotten.

Over the next few weeks I plan to highlight genre work by these forgotten HIBK authors. I begin with Anita Blackmon.

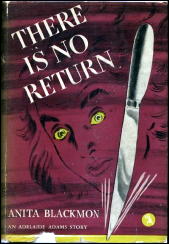

Anita Blackmon (1893-1943) published two mystery novels, Murder a la Richelieu (1937) and There Is No Return (1938). In the United States, both of Blackmon’s mysteries were published by Doubleday Doran’s Crime Club, one of the most prominent mystery publishers in the country.

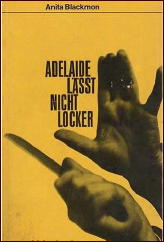

Murder a la Richelieu was published as well in England (as The Hotel Richelieu Murders), France (as On assassine au Richelieu) and Germany (as Adelaide lasst nicht locker), while There Is No Return was published in England also (under the rather lurid title The Riddle of the Dead Cats).

In classic HIBK fashion, Blackmon employed a series character in both novels, a peppery middle-aged southern spinster named Adelaide Adams (and nicknamed “the old battle-ax”).

In the opening pages of Adelaide Adams’ debut appearance, Murder at la Richelieu, Anita Blackmon signals her readers that she is humorously aware of the grand old, much-mocked but much-read HIBK tradition that she is mining when she has Adelaide declare, “had I suspected the orgy of bloodshed upon which we were about to embark, I should then and there, in spite of my bulk and an arthritic knee, have taken shrieking to my heels.”

Yet, sadly, Adelaide confides, “there was nothing on this particular morning to indicate the reign of terror into which we were about to be precipitated. Coming events are supposed to cast their shadows before, yet I had no presentiment about the green spectacle case which was to play such a fateful part in the murders, and not until it was forever too late did I recognize the tragic significance back of Polly Lawson’s pink jabot and the Anthony woman’s false eyelashes.”

Well! What reader can stop there? Adelaide goes on with much gusto and foreboding to relate the murderous events at the Hotel Richelieu, a lodging in a small southern city (clearly Little Rock, Arkansas; see below). Adelaide is a wonderful character: tough on the outside but rather a sentimentalist within, given to the heavy use of cliches yet actually rather mentally acute.

The life in and inhabitants of the old hotel are well-conveyed, the pace and events lively and the mystery complicated yet clear (and at the same time played fair with the readers). Perhaps most enjoyable of all is the author’s strong sense of humor, ably conveyed through Adelaide’s memorable narration.

Blackmon clearly knows that HIBK tales frequently are implausible and even silly in their convolutions and she has a a lot of fun with the conventions. Readers should have a lot of fun as well. Murder a la Richelieu emphatically deserves reprinting.

Blackmon’s follow-up from the next year, There Is No Return, is less successful. This tale finds Adelaide coming to the rescue of a friend, Ella Trotter, embroiled in mysterious goings-on involving spiritual possession at a backwoods Ozarks hotel, the Lebeau Inn (in fact the novel could well have been called Murder a la Lebeau).

Though Return opens with yet another splendid HIBK declaration in the part of Adelaide ( “As I pointed out, to no avail, when the body of the third disemboweled cat was discovered in my bed, had I foreseen the train of horrible events which settled over that isolated mountain inn like a miasma of death upon the afternoon of my arrival, I should have left Ella to lay her own ghosts”), the novel is less amusing than Richelieu, its character less interesting and its mystery less cogently presented and credible.

Yet it is still fun to encounter the old battle-ax one final time.

When Howard Haycraft published Murder for Pleasure in 1941, he clearly classed Blackmon as a major figure in the HIBK school, though she in fact had not published a mystery novel in three years. Two years later Blackmon would die at the age of fifty, and her fiction would be largely forgotten. I have discussed her genre work a bit, but have so far left unanswered this question: who was Anita Blackmon?

Anita Blackmon was born in 1893 in the small eastern Arkansas town of Augusta. The daughter of Augusta postmaster and mayor Edwin E. Blackmon and his wife, Augusta Public School principal Eva Hutchison Blackmon, both originally from Washburn, Illinois, Anita Blackmon revealed a literary bent from a young age, penning her first short story at the age of seven.

By all accounts, Blackmon grew up into a vivacious, attractive, outgoing young woman. The future novelist graduated from high school at the age of fourteen and attended classes at Ouachita College and the University of Chicago. Returning home from Chicago, she taught languages in Augusta for five years before moving to Little Rock, where she continued to teach school.

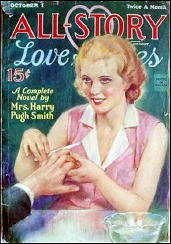

In 1920, Blackmon left teaching and married Harry Pugh Smith in Little Rock. The couple moved to St. Louis, where Blackmon had an uncle who served as a St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad vice president, and in 1922 Blackmon published the first of what would be over a thousand short stories. Blackmon’s short stories appeared in a diverse collection of pulps, including Love Story Magazine, All-Story Love Stories, Cupid’s Diary, Detective Tales and Weird Tales.

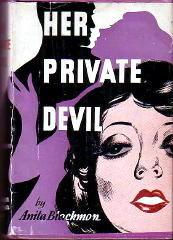

Blackmon began publishing novels in 1934 with a work entitled Her Private Devil, one that provoked some scandalized talk back in Augusta. Devil was published by William Godwin, a press, as described by Bill Pronzini, that specialized in titillating novels that pushed the sexual envelope of the day.

Godwin titles by other authors in the writing stable such as Delinquent, Unmoral, Illegitimate, Indecent, Strange Marriage and Infamous Woman give some idea of the nature of most Godwin fiction.

Blackmon’s book, which detailed the unhappy life of a southern small-town girl who gives into her strong sexual desires, is fairly bold, but by no means a “dirty” book. In actuality it is a serious study of a troubled young woman handled with considerable sensitivity and not especially explicit by today’s standards. Still, the book raised something of a stir in conservative Augusta, with some in the town expressing disapproval.

Over the next few years Blackmon published traditional, mainstream novels under the name Mrs. Harry Pugh Smith, some of which had been previously serialized, before concluding her run with her two mystery novels, published, like Her Private Devil, under her maiden name.

The best known of the Mrs. Harry Pugh Smith novels was Handmade Rainbows, a tale of middle class Depression-era life in small southern town very like Augusta. Part of the enjoyment one gets from Blackmon’s better novels stems from the author’s effective depiction of unique southern local color.

Blackmon’s Murder a la Richelieu clearly is set in Little Rock, where there was in fact a Richelieu Hotel, while There Is No Return is set far in the Ozarks. Certainly many Golden Age mysteries with Arkansas settings do not come to my mind!

Why Anita Blackmon produced no more Adelaide Adams mysteries in her last five years of life is a mystery itself. Blackmon died after a lengthy illness in a nursing home in Little Rock, where she moved after the death of her husband.

Perhaps under the circumstances she was not up to plotting and writing another full-length mystery novel, though she is said to have continued writing until shortly before her death. Though Blackmon’s mystery novel output is small, Murder a la Richelieu, at least, merits reprinting as a significant example of an HIBK tale.

Also worth noting are the many now-unknown short stories that Blackmon wrote, some of which (those published in Detective Tales) might well be of interest to mystery genre fans. Clearly, further delving is in order!

NOTE: Information on Anita Blackmon’s life was drawn from Woodruff County Historical Society, Rivers and Roads and Points in Between 3 (Fall 1975), pp. 21-22 and interviews with Rebecca Boyles and Virginia Boyles. Special thanks for his generous help to Kip Davis, Augusta City Planner.

Bibliography (Short Fiction; Incomplete) —

BLACKMON, ANITA

* * Glory That Flamed, (ss) Four Star Love Magazine Mar 1937

* * The High Heart, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Jun 28 1927

* * Love’s Precious Secret, (ss) Sweetheart Stories Feb 17 1926

* * The Mystery of Tip Top Inn, (sl) Sweetheart Stories Apr 14 1926

* * Under Another’s Name, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Dec 2 1925

* * With Hearts Aflame, (nv) Sweetheart Stories Mar 3 1926

SMITH, MRS. HARRY PUGH

* * Angel Face, (ss) Love Story Magazine Nov 27 1926

* * The Book of Death (nv) Weird Tales, Nov 1924

* * The Burnt Offering (?) Mystery Magazine, Aug 1 1922

* * Carnival Man, (ss) All-Story Love Stories Apr 15 1933

* * Chained [Part last of ?], (sl) All-Story Love Stories Nov 30 1935

* * Cheated, (ss) Cabaret Stories Jan 1929

* * The Colonel’s Daughter, (ss) Sweetheart Stories May 20 1930

* * A Cottage for Two, (ss) All-Story Dec 14 1929

* * The Devil’s Signet, (ss) Love Story Magazine Oct 31 1925

* * Double Motive (?) Detective Classics June 1930

* * Fettered, (ss) Love Story Magazine Sep 25 1926

* * Firecracker Kathy, (nv) All-Story Love Stories Jul 1 1932

* * Flower of Dusk, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Jun 12 1929

* * The Gay Deceiver, (ss) Love Story Magazine Oct 29 1927

* * Ghost Between [Part last of ?], (sl) All-Story Love Stories Feb 16 1935

* * Her Snobbish Dude, (ss) Far West Romances Jan 1932

* * The Hermit (?) Detective Tales Nov 16/Dec 15 1922

* * The Hindu, (ss) Detective Tales Feb 1923

* * An Interrupted Engagement, (ss) Love Story Magazine Dec 18 1926

* * The Jeweled Pin (?) Detective Tales Apr 1924

* * Jezebel, (ss) Breezy Stories Mar #2 1925

* * Little Lost Bride, (ss) Sweetheart Stories Jul 1935

* * Long Live the King!, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Dec 12 1928

* * Love at Last, (ss) Love Story Magazine Jan 2 1926

* * Love by Accident, (ss) All-Story Love Stories Apr 1 1933

* * The Love Fued, (ss) Love Story Magazine Nov 20 1926

* * Love’s Upward Trail, (ss) Love Story Magazine Jul 30 1927

* * The Marriage of Michael Malloy, (nv) All-Story Love Stories Mar 23 1935

* * Marry for Love, (ss) Sweetheart Stories Mar 1937

* * Marry Him If You Dare!, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Jan 30 1937

* * Maybe It’s Love, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Sep 19, Sep 26, Oct 3, Oct 10, Oct 17, Oct 24 1936

* * My Lady’s Dressing-Table, (vi) Breezy Stories Feb 1923

* * Object, Matrimony, (ss) All-Story Love Stories May 15 1933

* * One True Love [conclusion], (sl) All-Story Love Stories Sep 8 1934

* * The One-Track Heart, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Jan 18 1936

* * The Pride of Darcy, (ss) Love Story Magazine Nov 21 1925

* * Ranch Paradise, (nv) Street & Smith’s Far West Romances Jun 1932

* * The Sting of the Scorpion, (ss) Action Stories Feb 1923

* * A Tangled Skein, (ss) Love Story Magazine Mar 27 1926

* * The Town’s Bad Boy, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Mar 13, Mar 20, Mar 27, Apr 3 1937

* * With This Ring, (nv) All-Story Love Stories Jun 15 1932

* * The Yellow Dog (?) Detective Tales Oct 16 1922

SOURCES: The FictionMags Index; Mystery, Detective & Espionage Fiction, 1915-1974, Cook & Miller.