Sun 25 Oct 2009

Reviewed by William F. Deeck: HUGH AUSTIN – The Milkmaid’s Millions.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Crime Fiction IV , ReviewsNo Comments

William F. Deeck

HUGH AUSTIN – The Milkmaid’s Millions. Charles Scribner’s Sons, hardcover, 1948.

This is the second and apparently last in the “Sultan’s Harem” mysteries. The Sultan is Wm (that’s the way he spells it) Sultan, the only surviving member of Sultan, Sultan & Sultan, counselors at law.

Wm is thirty-five years old, but talks and thinks as if he were in his seventies. His staff, all female and thus “the harem,” treats him as if he were their grandfather, though his secretary appears to regard him as a possible swain.

Wm’s main interest in life is compiling his late uncle’s “Life & Letters.” His staff is typing up the forty-second chapter of the second volume, which seems to comprise the twenty-seven thank-you letters the uncle sent for presents received on his fourteenth birthday.

One shudders to think what the other forty-one chapters in volume two might consist of, and volume one doesn’t bear thinking about at all.

One of Wm’s few clients has prepared a codicil to his will, having recently discovered a direct descendant, and Wm is called upon to prove the bona fides of the new family member. Shortly after Wm arrives at the client’s home, however, the testator is murdered.

The investigators think that Wm did it, evidence arises that Wm probably didn’t do it, and then new developments seem to demonstrate that he did indeed do it.

Wm’s harem, who were responsible for his getting involved in the mess, arrives on the scene to vamp some of the suspects and rig some evidence so that Wm will not be convicted of the crime. Those who enjoy the pedantic and stuffy, mixed with the preposterous, will find this novel delightful. The crime’s rather good, too.

Bibliographic Data. [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.] —

AUSTIN, HUGH. Pseudonym of Hugh Austin Evans.

It Couldn’t Be Murder (n.) Doubleday 1935 [Peter Quint]

Murder in Triplicate (n.) Doubleday 1935 [Peter Quint]

Murder of a Matriarch (n.) Doubleday 1936 [Peter Quint]

The Upside Down Murders (n.) Doubleday 1937 [Peter Quint]

The Cock’s Tail Murder (n.) Doubleday 1938 [Peter Quint]

Lilies for Madame (n.) Doubleday 1938.

Drink the Green Water (n.) Scribner 1948 [Wm Sultan (Sultan’s Harem)]

The Milkmaid’s Millions (n.) Scribner 1948 [Wm Sultan (Sultan’s Harem)]

Death Has Seven Faces (n.) Scribner 1949.

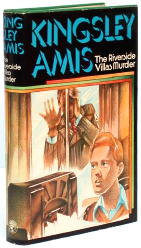

Peter Quint was a lieutenant in the New York City police department. The small cover image of The Cock’s Tail Murder seen above (by Artzybasheff) is the only one of Austin’s books that I’ve been able to come up with so far in jacket. No other information about the author, other than his real name, seems to be known.

[UPDATE] Later the same day. British bookseller Jamie Sturgeon has just supplied me with another cover, this one for The Upside Down Murders. It came from a Grosset reprint, but both he and I believe it to be the same as the Crime Club edition. Art by Duggaru:

[UPDATE #2] 10-26-09. Thanks to the combined efforts of Victor Berch, Jamie Sturgeon and Al Hubin — and Google! — it has been learned that Hugh Austin Evans was born in 1903 and died in 1964.