FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

If there’s ever a biography of Ellery Queen—not of the detective character but of the cousins Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee who created Ellery and also used his name as their joint byline—the following incident from Fred’s life deserves to be included.

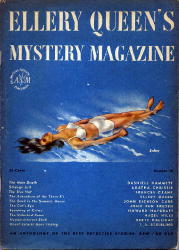

The first part comes mainly from one of the long introductions that he wrote for each story published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine during its early years; the follow-up was unearthed by radio historian Martin Grams, Jr. and will appear in one of his forthcoming books.

In the spring of 1946, soon after being discharged from the Army at the end of World War II, Dashiell Hammett arranged with “a certain school of social science in New York City” to offer a Thursday evening course on mystery fiction aimed at writers and writer wannabees.

At this time Fred’s main tasks in life were keeping EQMM afloat and, after his wife’s death from cancer, raising two young sons. He read the announcement of Hammett’s course and was impelled by curiosity to attend the first session, on May 2.

Hammett invited him on the spot to co-teach the course and Fred agreed, each two-hour stint followed by “all-night bull-and-brandy sessions” between those giants of crime fiction. At the end of the May 16 class a young woman named Hazel Hills Berrien approached Fred and offered him the manuscript of a story she had begun writing after the first session.

Fred, as always, suggested certain changes — “in the character of the detective, in the plot construction, and in the title,” he said later—but when they were made to his satisfaction, he bought the tale, which appeared in EQMM for September 1946 as “The Unlocked Room” by Hazel Hills.

Then as now, magazines appeared on the stands some time before the publication month listed on their front covers, and the September EQMM had been available at least for a few weeks before August 31, 1946. That evening’s episode of the popular ABC radio series The Green Hornet was called “Death in the Dar” and dealt with a civil servant accused of embezzlement who is found shot to death in a room with the door locked and the window bolted. Newspaper publisher Britt Reid, a.k.a. the Green Hornet, rejects the obvious theory of suicide and eventually proves that the man was murdered.

Hazel Hills Berrien wrote ABC four days after the broadcast, admitting that she hadn’t heard the episode but claiming she’d been told by a friend that it “bore a peculiar resemblance to a recently published short story of mine.”

In this and several subsequent letters, each more threatening than the last, she demanded a copy of Dan Beattie’s script but refused to send ABC’s lawyers a copy of her story.

Eventually Fred heard of the dispute and, on October 11, wrote to Green Hornet creator George W. Trendle, promising a copy of September’s EQMM and asking in return for a copy of Beattie’s script.

Four days later and after reading “The Unlocked Room,” Trendle replied to Fred, rejecting any allegation of plagiarism but saying: “[H]ad Miss Hills handled the matter as diplomatically as you have, I think a copy of our script would have been in her hands long ago.”

A later letter to Fred from Green Hornet attorney Raymond Meurer made the same point: “[W]e regret that the matter was handled so clumsily by Miss Hills…. [H]ad we received the request originally from you, we would not have hesitated a moment in supplying the script.” The tempest in a teapot quickly blew away since the only similarity between Hills’ story and the Hornet script was that both involved a murder in a locked room with a gimmicked window.

As far as I know Hills never wrote another story, certainly none published in EQMM.

Among the reprints in the EQMM issue that contained Hills’ story was one by Agatha Christie (“Strange Jest,” a Miss Marple tale originally published in 1941), again with an introduction by Fred Dannay, this one quoting a stanza from one of Christie’s poems.

It comes from “In the Dispensary,” which was included in her collection The Road of Dreams (Bles, 1925):

From the Borgias’ time to the present day, their power

has been proved and tried:

Monkshood blue, called aconite, and the deadly cyanide.

Here is sleep and solace and soothing of pain—

courage and vigour new;

Here is menace and murder and sudden death—in these

phials of green and blue.

Okay, so it’s doggerel. Thanks anyway, Fred, for giving me this item for my column’s Poetry Corner more than sixty years ago!

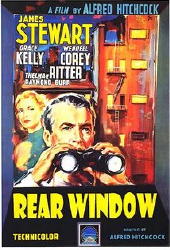

John Michael Hayes (1919-2007) never wrote a mystery novel or short story but, thanks mainly to his screenplays for several Alfred Hitchcock films, most notably Rear Window (1954) and the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), his memory remains green for us.

I recently had occasion to read a deposition Hayes gave in August 1991 in connection with some litigation over Rear Window and was delighted to find some information about Hitchcock’s connection with Cornell Woolrich that I believe has never appeared in print.

Among the six tales brought together in the second collection of Woolrich’s short fiction (After-Dinner Story, as by William Irish, 1944) were “Rear Window” (first published under Woolrich’s own name in Dime Detective, February 1942, as “It Had To Be Murder””) and “The Night Reveals” (first published in Story Magazine for April 1936).

Hitchcock was interested in both. Shortly after Hayes began working on the Rear Window screenplay, “Hitch asked me…if I would read [“The Night Reveals”] and comment on it because he had [had] a choice between the two stories and wanted to know if he’d made the right choice. And I said he certainly had because “Rear Window” lent itself to intense suspense material and intense personal relationships which the other story didn’t.”

Still and all, “The Night Reveals” is also marked by powerful suspense scenes and an intense relationship—between insurance investigator Harry Jordan and his wife, who he comes to suspect is a compulsive pyromaniac—and it’s a shame Hitchcock didn’t at least use it as source for an episode of his TV series. Preferably one directed by himself.