Sat 30 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: JAMES M. CAIN – Double Indemnity.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Authors , Crime Films , Reviews[4] Comments

JAMES M. CAIN – Double Indemnity.

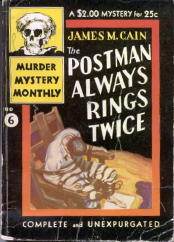

Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #16; paperback original, 1943. First published in Liberty magazine in 1936 as the eight-part serial “Three of a Kind.” First hardcover edition: included in Three of a Kind (Knopf, 1944) with “Career in C Major” and “The Embezzler.” Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and paperback, including Avon #60, 1945 (shown).

Film: 1944, with Barbara Stanwyck & Fred MacMurray; adapted for the screen by Raymond Chandler and Billy Wilder.

James M. Cain wrote of “the wish that comes true … I think my stories have some quality of the opening of a forbidden box, and that it is this rather than violence, sex or any of the things usually cited by way of explanation that gives them the drive so often noted.”

Double Indemnity employs this same technique, already displayed in The Postman Always Rings Twice, with dazzling ease. Cain, making a quick buck writing a magazine serial in 1936, did not realize it at the time, but he was at the top of his form. Employing skillful, scalpel-like first-person narration, Cain tells his tale of love and murder from the point of view of a lover and murderer.

Insurance man Walter Huff becomes embroiled in a plot to kill a beautiful woman’s husband. In addition to the sexual and financial incentives, Phyllis Nirdlinger manages to play upon Huff’s boredom and his pride – he knows the insurance game inside and out, and figures with his expertise he can beat it.

The husband is murdered, according to Huff’s plan, without a hitch. But Huff is dogged by Keyes, a claims agent who also knows the insurance game inside and out. Huff begins to realize Phyllis is untrustworthy and just possibly insane, and falls in love with Lola, the daughter of the murdered man by a previous wife, who had very probably been yet another murder victim of Phyllis’s.

Double Indemnity is a murder mystery turned inside out: We are forced inside the murderer’s skin, only to find it uncomfortably easy to identify with him, and then share his paranoia as the world crumbles piece by piece around him.

Huff is a white-collar worker and he’s smart – smart enough to sense early on just how major a mistake he’s made. His sense of his own frailty and wrongdoing makes him a truly tragic protagonist, as does his sense of loss: “I knew I couldn’t have her and never could have her. I couldn’t kiss the girl whose father I killed.”

Cain liked to explore the workings of businesses, and he never did it better than in Double Indemnity, through the characters of Huff and Keyes. But he also gave the pair an understated shared understanding of humanity (an aspect broadened in the widely respected Billy Wilder-directed, Raymond Chandler-scripted film version of 1944).

In their final confrontation, Keyes says to Huff (renamed Neff in the film), “This is an awful thing you’ve done, Neff,” and Huff/Neff only says, “I know it.” And when Keyes says, “I kind of liked you, Neff,” Huff/Neff says, “I know. Same here.”

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.