A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

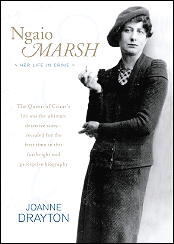

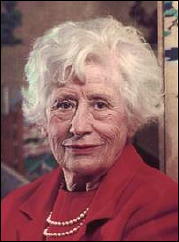

JOANNA DRAYTON – Ngaio Marsh: Her Life in Crime. HarperCollins, Australia, hardcover, January 2008; softcover, 2009.

The first biography of Ngaio Marsh following Margaret Lewis’s Ngaio Marsh: A Life (1991, reprinted by Poison Pen Press, 1998), is this book by Joanna Drayton. Published by HarperCollins of New Zealand, it is evidently unavailable for direct purchase in the United States, providing, perhaps, further evidence that big publishers are losing interest in marketing Golden Age British authors in the their greatest potential market (Christie and Sayers excepted).

In Britain, Harper recently has reprinted Marsh’s ouevre in three-volume, 800-plus page ominbuses; yet in the U.S. no new edition has been seen, I believe, since the late 1990s, about a dozen years ago. This is a shame, because I notice from Amazon.com reviews that Marsh seems to be more positively received in the U.S. than in Britain; and in New Zealand, Marsh’s home turf, she has been, according to Joanne Drayton, largely forgotten as a writer. (Rather amazingly, considering that she must be, one would think, the country’s best-selling native author.)

Perhaps this explains why it has been hard to find reviews for Drayton’s book, which was published two years ago. When one compares the publicity in Britain given to the 2008 biography of Agatha Christie (the first substantive new one in nearly twenty-five years), Laura Thompson’s Agatha Christie: An English Mystery, with the paucity of that afforded Ngaio Marsh: Her Life in Crime, the contrast is striking. It’s too bad, because Ngaio Marsh unquestionably is one of the most significant writers of classical mysteries associated with Britain’s Golden Age of detective fiction.

Yet, while I would have liked for Drayton’s book (and resultingly Ngaio Marsh) to have received more attention than it did, I have mixed feelings about how much it has added to the prior work on Marsh by Margaret Lewis.

First, a comment on physical aspects of the two books. HarperCollins designed an excellent, striking jacket, attractive endpapers and chapter headings and even provided a built-in book marker in the manner of Library of America, all of which is quite nice to see (though, as is often the case today, the paper is too thin and the print too light and indistinct, especially in contrast with the Poison Pen Press edition of Lewis’s book).

However, I was rather amazed to see that the Drayton book, though it has notes and a select bibliography, is lacking an index! I find that quite irritating.

Going on — finally — to the subject matter, I find the Drayton book superior to the Lewis in some ways, inferior in others. On the negative side, Drayton’s book seemed less informative on Ngaio’s youth and her parents, especially her father, than Lewis’s. I felt I learned more about Marsh’s home influences and family background from Lewis.

Drayton gives much more information about Marsh’s life in the theater, but then Lewis writes a great deal about this as well. (I admit these sections of both books I skimmed over.)

On the other hand, Drayton’s discussions of Marsh’s detective novels are superior to those by Lewis. This was an area I felt Lewis rather skimped, given the importance of this work. (Let’s be honest: would two biographies of Ngaio Marsh have been published had Marsh not been a very successful mystery author.)

Nonetheless I was not fully satisfied with Drayton’s discussion of the books. She never really integrates themes throughout Marsh’s work, so the whole thing comes off as interesting in spots, but piecemeal (the discussions of the later books from the last fifteen years of Marsh’s life are less thorough as well — or are the books just less interesting?). Drayton provides a better Golden Age context for Marsh’s writing, yet it’s really just the four “Crime Queens” yet again.

The sole focus on the Crime Queens is somewhat ahistorical in my view. For most of the Golden Age, there were two reigning Crime Queens: Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers.

Allingham didn’t really fully emerge in her resplendent royal robes until the trio of Flowers for the Judge (1936), Dancers in Mourning (1937) and The Fashion in Shrouds (1938), I would say.

And Marsh was not well recognized until after her trio of Artists in Crime (1938), Death in a White Tie (1938) and Overture to Death (1939).

Even then, Marsh was only picked up by a big U.S. publisher, Little, Brown and Company (publishers of J. J. Connington), after Overture to Death was published; and it was Little, Brown who secured Marsh’s crown safely on her head with Surfeit of Lampreys (1940/41), still today generally considered her best book.

So while Allingham and Marsh were Crime Queens, their reigns commenced during the waning of the Golden Age. (Arguably, they had something to do with that waning, at least if by “Golden Age” we mean a period when the puzzle was considered the keystone of the detective novel — it’s clear many readers read Marsh and Allingham more as novels of manners than as pure detective novels.)

We also get the usual W. H. Auden stuff about how “normality was always restored” in Golden Age detective novels, etc. Well, that’s not true, but, hey, hopefully I’ll get my whack at this in print with the “Humdrum” books and the follow-up, more general survey I’m working on now.

Despite my carping, I’ll emphasize again that the discussion of Marsh’s detective fiction is more interesting in Drayton than in Lewis (though make sure you read Doug Greene’s introduction to Alleyn and Others: The Collected Short Works of Ngaio Marsh as well!).

Sometimes Drayton is a little ingenuous. She makes much of the “Marsh Million Murders” (this is a chapter title in her book), when, in 1950, I believe it was, Penguin reprinted ten Marsh titles in 100,000 printing runs. (Lewis noted this as well, but did not make such a fuss about it.)

Drayton references Howard Haycraft in Murder for Pleasure from nearly a decade earlier about how the average detective novel sold only 1500-2000 copies (because most were read through libraries, not purchased).

But Drayton is comparing apples and oranges to some extent here. Clearly, the Marsh Penguin deal is impressive, but Drayton needed to look at post-war paperback sales of other authors for a really accurate comparison. This was the time of the great paperback revolution and other authors, like, say, Spillane, Chandler and Stout were blowing them out in paperback too, surely.

I smiled a bit when Drayton wrote that Marsh’s output of ten novels in seven years was “extraordinary.” Well, it’s certainly not slacking, but it’s not extraordinary by genre standards of the time, as a look at the output of, say, Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Freeman Wills Crofts or John Street makes clear.

I was reminded of an old SCTV skit where Olivia Newton John gets booked on a talk show with some porn stars and when they find out she’s made nine films or what have you in her whole career, they scoff, telling her they make nine films in a month!

To be fair, however, Lewis had some odd moments too, like when she writes that The Nursing Home Murder is Marsh’s most popular book — can this really be right? there is no citation of this claim — and when she states that that in the U.S. after WW2 Marsh was “much preferred” to Agatha Christie, because people there no longer wanted to read about Hercule Poirot.

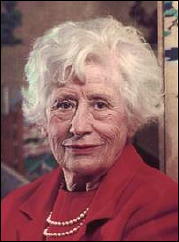

However, Drayton’s book is a biography, not a literary study, so presumably some people will be most interested in this book for what it tells us about Marsh’s personal life. The big story here is Drayton speculates about Marsh, having been a lesbian, something the previous biographer eschewed doing.

Marsh “was fiercely protective of her private life,” the jacket flap tells us, “No one knows better how to cover tracks and remove incriminating evidence than a crime fiction writer.” I find the “A-ha! we caught her out!” tone of this comment rather distasteful. To incriminate means to accuse someone of a wrongful act — surely HarperCollins did not mean to take the position that lesbianism is “wrongful.”

Be that as it may, Drayton writes more in depth about a life-long female friend of Marsh’s, Sylvia Fox, than did Lewis, who only mentioned Fox sporadically. Drayton says she left the matter of whether Fox and Marsh had a lesbian relationship for readers to decide, though I think it’s pretty clear from her book that she implies that they did.

The two women apparently took several trips together. Fox in 1963, when both women were in their late sixties, moved to a cottage that neighbored Marsh’s and a path was cut though a hedge so that they could conveniently visit each other.

When Marsh was nearing death she destroyed a lot of papers (that “incriminating” evidence?). When Fox died a decade after Marsh, her headstone was placed beside Marsh’s. “They were the closest of friends, companions and neighbours in life and will be for eternity,” Drayton concludes. (This is even the concluding line of the book.)

I had always wondered myself whether Marsh might have been a lesbian. I suppose Drayton’s book moves the ball somewhat in that direction; yet Marsh “always” denied she was a lesbian, according to Drayton and it’s certainly possible that the two women may merely have been close friends. Who knows?

The larger problem with Drayton’s book as a biography is that it never really gets us any closer to the personality of the woman than Lewis’s. (Indeed, Lewis may have been a bit better here.) Marsh was a very guarded person and thus a tough nut to crack in a biography.

Lesbianism does not seem to have been a theme of Marsh’s books, even implicitly. (There is a lesbian character in Singing in the Shrouds, whom, oddly, Drayton does not discuss.)

Gay men appear in her books, invariably, as I recall, as stereotypical “queen” types — amusing up to a point, but hardly different from conventional portrayals. In contrast with Mary Fitt, who definitely was a lesbian, and Gladys Mitchell, who has been said to have been one, I do not really get that “feel” from Marsh’s books.

Thus, while the matter of Marsh’s sexuality probably at this late date will never be resolved, I’m not sure how relevant it is to her analyses of her work anyway.

So, should you buy this book? If you have the Lewis already, I’d say it’s a judgment call. On the whole, I would say Drayton’s is the more interesting work, but the Lewis has some points in its favor as well. Meanwhile, there’s still room for a really definitive critical study of the woman’s book on crime, which to me are even more interesting than her “life in crime.”