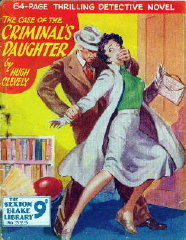

HUGH CLEVELY – The Case of the Criminal’s Daughter

Sexton Blake Library #323; The Amalgamated Press. Paperback. No date given.

As it says, this slim (if not flimsy) 64-page digest-sized paperback comes with no bibliographic information, but luckily for those with Internet access, help is just a few keystrokes away. There is a website devoted to all things Sexton Blakian, and where the link will take you, you will discover that this is #323 of the Third Series of the Sexton Blake Library. The stories appeared monthly; this is the one that came out in November, 1954. And the illustrator responsible for the cover art was none other than Reginald (Heade) Webb.

This being only the first Sexton Blake novel I’ve read in some 20 years, and the second overall, there’s no way I will talk in any general way about the character, nor should I, except to say that he, Sexton Blake, appeared as a character in over 3000 stories written by some 200 authors over a period of well over a century.

As for Hugh Clevely, well, first of all, he was one of the 200 authors who wrote stories about Sexton Blake, but of course you knew that, or you should have. According to Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, however, he only wrote 10 other Sexton Blakes, at least in novel form. His overall writing career spanned the years from 1928 to 1955 and includes a list of 35 novels under his own name, one co-written with Edgar Jepson. Only four of these novels have been published in the US.

As Tod Claymore, he wrote another eight mysteries, all with a series character named Tod Claymore. According to W. O. G. Lofts and Derek Adley’s website The Crime Fighters, “He [Claymore] had been a Wimbledon tennis player and a wing commander during the war, then switched to writing, with detection as a hobby.” Some of these books were imported or published in this country as Penguin paperbacks, the green ones.

Returning to the books Clevely wrote under his own name, the series characters that appeared in them were Chief Inspector Williams, Maxwell Archer, J. D. Peters, and John Martinson. According to a New York Times review of a film based on one of the Maxwell Archer books, the latter was a “famed fictional private detective whose greatest pleasure in life is to second guess Scotland Yard…” The occupations of the other series characters remain either unknown or quite guessable.

So Clevely was an experienced mystery writer when he started doing the Sexton Blake books, which were all written toward the end of his career. All eleven of them appeared in the four-year period from1952 to 1955. Does the experience show? It does and as the saying goes, it doesn’t.

The plot of the case in point, that is to say the book in hand, is a complicated one, and the pace is a lively one, but there’s a considerable amount of what is generically called sloppiness in the details, making you wonder if it were written too fast for a market that didn’t offer very much in compensation.

The criminal in the title is a circus performer (billed as The Great Costello) who once spent some time in jail, but who now is worth a considerable amount of legitimate money. His brother is a ne’er-do-well who is currently in a jam with some British style hoodlums. Add in the fact that Pat Costello, the acrobat, does not know he has an American daughter, but after his death by misadventure – deliberate – the fact of her existence – and that she is on a schoolgirls’ trip in Europe – means a lot to everyone who’s involved. There is also a not-so-small matter of some missing diamonds, and there (without going into further details) you have the basis for a decent if not overly rousing mystery for private enquiry agent Sexton Blake, his assistant Tinker, and Inspector Fosdyke to solve.

The details that the author works into the story, a rather pulp-like yarn, help to make the story more of a something than it is, along with a few twists in the tale that I frankly didn’t see coming. It was more than enough for me to start searching out more of the entries in Sexton Blake’s long history, but –

– some of the details don’t fit, or they clash with other ones. The conversation that Blake has with newspaper journalist Peter Grayson on page 26, for example, makes it seem that he had never heard of the girl Josie Benson before, whereas on page 23 the same two gentleman had a long conversation about the very same girl, and what Grayson should do to contrive to meet her. On page 53 Grayson and the girl are being held captive in a Martello Tower, he in a handcuff that severely restricts his range of motion – yes, that’s the kind of thriller this is – but the handcuff is never mentioned again, nor is there any restriction on his range of motion, when it comes time to attempt an escape.

And yes, of course, such a point in time does come, and not too soon at that.

— May 2006

GILBERT CHESTER – The Man Who Wouldn’t Quit.

Sexton Blake Library #74; Amalgamated Press. Paperback. No date stated.

Once again the Sexton Blake website comes galloping to the rescue. This is #74 of the Third Series, published in June, 1944. The date being in the midst of World War II, and by some reckoning among the darkest days of the war, I wondered how scarce this book (thin, digest-sized, but 100 pages long) might be. I was right. There are no other copies to be found anywhere on the Internet, and while I do apologize, mine’s not for sale.

Gilbert Chester was the pseudonym of one H. H. Clifford Gibbons (1888-1958), whose total criminous output totaled approximately 100 novels, all but a handful of them Sexton Blakes, either anonymously or under his pen name, beginning in 1923 and continuing on through 1949.

And if I knew more, I’d tell you, but I don’t, so I’ll get right to the story this time. And what a great first chapter this story has! It’s one that’s designed to grab the reader right in from the start, or maybe I’m just a sucker for stories taking place on trains, beginning with a frightened girl who enters Fenton’s compartment just as the train is leaving the station. She hurriedly tells him that she’s going to bale out before the next stop and furthermore requests that if he’s ever asked, he should say that never saw her.

From page 4:

“Forget you’ve ever seen me.”

“I’m not the type to quit, I assure you.”

“Then you’re asking for trouble, sure enough. Well, are you going to play up?”

She jumps, and so (without much hesitation) does he. And of course he has no idea where they are or into what kind of trouble he’s leapt into.

Chapter Two can hardly compete with this, but it nearly does. Dropped off by the mysterious girl at Professor Barton’s home (where he had been heading) after a short hike and a longish drive in the dark, Fenton (a research scientist) is surprised to find himself in the morning a prisoner, with another young girl holding the key to his cell-like room.

Chapter Three. We have nearly forgotten about Sexton Blake by this time, speaking collectively for myself alone, but the author hadn’t. Another young lady calls on Blake to solve a problem for her – her bungalow is being tampered with. Someone has been entering and prowling about while she is away. By an invisible man, she claims. No one has seen anyone enter or leave.

It seems like a minor problem, but Blake takes the case, thinking her recitation too theatrical and wondering what could be behind such a fanciful tale. And of course, there is a surprise in store, and not only to Sexton Blake. On page 22 they discover a body in her locked and sealed home, riddled with lead – the body, that is.

If some care had been taken, this could have been quite a mystery to unravel, but Blake makes it look easy. With only a cursory examination, Blake suggests a solution – and a rather ingenious one – to Inspector Briggan after he shows up, and of course Blake’s right and I have no idea how he did it. But it certainly is ingenious.

In any case, no more details from me. You will have a find a copy of this book for yourself, if you’d like to know more. Suffice it to say that the opening three chapters are the best, but Chester certainly makes a more than competent story out of the rest of it.

Some additional comments, though: Chapter Six is a long, ten-page conversation between two of the characters (already alluded to) which manages to both be informative and entertaining and moves the plot along while at the same time not being a mere recitation of topics and events that each of the two participants already know. It’s a neat trick, if you (as an author) can do it. Try it sometime and see.

The weakest links in the chain of the narrative are (I sadly acknowledge) Sexton Blake’s own deductions, which consist almost entirely of whole cloth and gauze and mirrors, which is (I also admit) one heck of a way to run a railroad, um, detective novel. The gaps could have been fixed, but it is entirely to Mr. Chester’s credit that the story is still is as enjoyable as it is, even if they weren’t, and they never will be.

When I was a kid and growing up, I read a lot of Robert Louis Stevenson’s work, as did a lot of kids my age, but I never read The Wrong Box, nor have I rectified that omission any time since. It was published in 1889, which would have made it a contemporary novel instead the period piece it obviously was in 1966.

When I was a kid and growing up, I read a lot of Robert Louis Stevenson’s work, as did a lot of kids my age, but I never read The Wrong Box, nor have I rectified that omission any time since. It was published in 1889, which would have made it a contemporary novel instead the period piece it obviously was in 1966.

In 1947, it was Joan Leslie who was the star, one of a number of leading roles she had for smaller companies like Eagle-Lion, and her career lasted long enough, thanks to television, for her to be given a walk-on role in the remake as a guest at a party. She was full-faced and very pretty without quite being beautiful, but then again your opinion need not necessarily be the same as mine.

In 1947, it was Joan Leslie who was the star, one of a number of leading roles she had for smaller companies like Eagle-Lion, and her career lasted long enough, thanks to television, for her to be given a walk-on role in the remake as a guest at a party. She was full-faced and very pretty without quite being beautiful, but then again your opinion need not necessarily be the same as mine.