Sat 2 Jun 2007

Review: PHILIP MacDONALD – The Rasp.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews[6] Comments

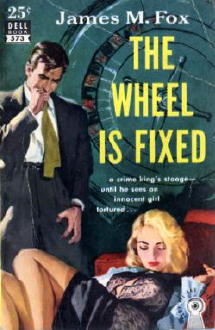

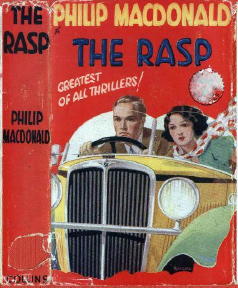

PHILIP MacDONALD – The Rasp

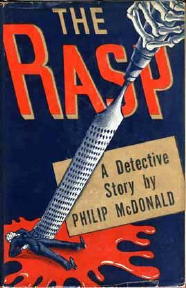

British hardcover: Collins, 1924 (see photo). US hardcover: Dial Press, 1925. Hardcover reprints (US): Scribner’s (S.S.Van Dine Detective Library), 1929; Mason Publishing Co., 1936 (see photo). Contained in Three for Midnight (with Murder Gone Mad and The Rynox Murder), Nelson Doubleday, 1962. Paperback reprints (US): Penguin #586, 1946; Avon G1257, 1965; Avon (Classic Crime Collection) PN268, 1970; Dover, 1979; Vintage, June 1984 (see photo); Carroll & Graf, 1984.

There was a British film based on the novel that came out in 1932, and Philip MacDonald also wrote the screenplay. According to IMDB, the featured players that appeared in the movie were Claude Horton (as Anthony Gethryn), Phyllis Loring (Lucia Masterson), C.M. Hallard (Sir Arthur Coates), James Raglan (Alan Deacon), Thomas Weguelin (Inspector Boyd), Carol Coombe (Dora Masterson) and Leonard Brett (Jimmy Masterson). If you think you’d like to see this on DVD sometime soon, so would I, and so would a lot of other people. This is a “lost” film, with no known copies in existence.

I hadn’t realized it before this, but MacDonald was involved in a good number of other movies, all as author of the original story, as screenwriter, or — as also with Rynox, also made in 1932 — both. I’ll go into some of the other fare at some other time, but the good news for Rynox is that after also having been lost for 40 years, it turned out to only have been misplaced. A print was discovered in 1990 after 50 years in the Pinewood Studios vaults, acquired by the National Film Archive and transferred onto safety film. Is it on DVD yet? Probably not, but maybe?

As for the book itself, now that my usual opening digression is over, a nice copy of the British first in jacket will set you back, I am sure, a figure in the low four-digit range. If all you care to do is to find a copy to read, you shouldn’t have to pay more than three or four dollars. Although I have several other editions, the one I just read was the 1984 edition from Vintage Books, and as far as the story’s concerned, there was still plenty of value left.

As a Haycraft-Queen Cornerstone title, there may be more value from historical perspective than there is from a pure story point of view, although I was certainly entertained all of the way through. On the other hand, most readers of contemporary detective fiction will probably not get all that far into it, if they even pick it up in the first place.

This was MacDonald’s first book. It was therefore also obviously the debut of his long-time detective character, Colonel Anthony Gethryn. Gethryn’s career started fast, with ten recorded cases between 1924 and 1933, then one in 1938, followed by a long gap until The List of Adrian Messenger came out in 1960. (There may have been some shorter fiction that appeared in the interim, but during the war years, there was very little if anything that MacDonald produced in the way of mystery fiction.)

To most mystery readers day — to return to the thought I was having a paragraph or so before — a book that was written in 1924 is going to appear as a period piece, stodgy, if not out-and-out primitive. The “rules” of detective fiction were still being formalized — what constituted “fair play” and all that goes with it. This comment does not apply to thrillers, for which authors had other objectives.

Working largely without a “Watson” to bounce his ideas off of, Gethryn notices a lot of things but often keeps them to himself, or at least the significance of them, which helps to explain the necessity of the entirely remarkable 46 page letter that Gethryn writes to the police afterward, laying out in immaculate detail all of his thought processes as he worked his way through the case.

Let me repeat that. Forty-six pages. Is there a denouement longer than this to be found in any other work of detective fiction?

Dead, you may (at last) be interested in knowing, is a noted member of the government. A cabinet minister, in fact, a fellow named John Hoode. The murder weapon is the titular woodworking tool. The place, the study in Hoode’s country residence. The suspects are primarily the few friends, relatives, staff and servants who were also in attendance that fateful evening, as Gethryn soon eliminates The Woman in the case, to his relief, for he has become madly infatuated with her. She is Mrs. Lucia Lemesurier, a widow — her previous husband apparently being eliminated in the movie version — as soon as he meets her it is with an all-but adolescent passion that renders him near speechless in her presence.

Accused by the C.I.D. is Hoode’s secretary, Alan Deacon, to whom all of the evidence seems to point. This includes the most damning: his and only his fingerprints were found on the woodmaking murder weapon. There is a good summation of the facts against Deacon on page 121. Gethryn demurs, however, and reassures the gentleman’s lady friend that all shall be well.

Another detective writer’s creation is mentioned on page 43, where Gethryn declaims somewhat unhappily:

For the most part, however, Gethryn putters about most happily, this game of investigation invigorating him no end, ending days of malaise after his return from the war (the first one). Most of Chapter Two is a mini-biography of Anthony Ruthven Gethryn, for those who would like to know more, but in essence he is the well-to-do bored genius, who needs the incentive of a murder to be solved to be at ease with himself.

At least that’s his persona in this, his first appearance. Whether, like Ellery Queen, he changed over the years, at the moment I cannot tell you. Perhaps you can tell me.

PostScript: I found another quote that I intended to include, and I didn’t. I can’t find an appropriate place to put it now, without interrupting whatever train of thought I was riding at a particular juncture, so I’ll put it here. What this seems to do is reinforce several of the ideas I was working on, especially toward the end of what I was saying. From pages 111-112, with Gethryn visiting Lucia in her drawing room:

“You,” said Lucia, “ought to be asleep. Yes, you ought! Not tiring yourself out to make conversation for a hysterical woman that can’t keep her emotions under control.”

“The closing of the eyes,” Anthony said, opening them, “merely indicates that the great detective is what we call thrashing out a knotty problem. He always closes his eyes you know. He couldn’t do anything with ’em open.”

She smiled. “I’m afraid I don’t believe you, you know. I think you’ve simply done so much to-day that you’re simply tired out.”

“Really, I assure you, no. We never sleep until a case is finished. Never.”

PostScript #2. I really do not know what to make of the cover of the paperback edition that I read.

UPDATE [06-02-07] I’ve belatedly decided to include a list of all of the Gethryn novels. UK editions only, but the US titles are given if they were changed. Taken from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

* The White Crow (n.) Collins 1928 [England]

* The Link (n.) Collins 1930 [England]

* The Noose (n.) Collins 1930 [London]

* The Choice (n.) Collins 1931 [England] US: The Polferry Riddle

* The Wraith (n.) Collins 1931 [England; 1920]

* The Crime Conductor (n.) Collins 1932 [London]

* The Maze (n.) Collins 1932 [London] US: Persons Unknown

* Rope to Spare (n.) Collins 1932 [England]

* Death on My Left (n.) Collins 1933 [England]

* The Nursemaid Who Disappeared (n.) Collins 1938 [London]

* The List of Adrian Messenger (n.) Jenkins 1960 [London]