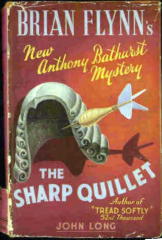

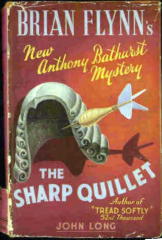

BRIAN FLYNN – The Sharp Quillet. John Long, hardcover, no date stated (1947). No US edition.

You’ll have to fasten your seatbelts, because I’m going to begin this review with a list of Brian Flynn’s mysteries, and it’s going to be a long one. Taken from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, these are the British titles only. Most of these were published only in England, but those preceded by (**) did have US editions.

The detective in every one of these works of crime fiction is a chap named Anthony Bathurst, and since he’s in the book at hand, there will be more about him in a minute. At the present time, there’s no year of death given for his author, Brian Flynn, and I’ll ask a couple of people what they might know about that. First, though, the list of titles:

FLYNN, BRIAN (1885- ) An accountant in government service, a lecturer in Elocution and Speech, an amateur actor.

** The Billiard-Room Mystery (n.) Hamilton 1927.

** The Case of the Black Twenty-Two (n.) Hamilton 1928.

** The Mystery of the Peacock’s Eye (n.) Hamilton 1928.

** The Five Red Fingers (n.) Long 1929.

* Invisible Death (n.) Hamilton 1929.

** The Murders Near Mapleton (n.) Hamilton 1929.

** The Creeping Jenny Mystery (n.) Long 1930.

** Murder En Route (n.) Long 1930.

* The Orange Axe (n.) Long 1931.

* The Triple Bite (n.) Long 1931.

* The Edge of Terror (n.) Long 1932.

* The Padded Door (n.) Long 1932.

* The Spiked Lion (n.) Long 1933.

** The Case of the Purple Calf (n.) Long 1934.

* The Horn (n.) Long 1934.

* The League of Matthias (n.) Long 1934.

* Tragedy at Trinket (n.) Nelson 1934.

* The Sussex Cuckoo (n.) Long 1935.

** Fear and Trembling (n.) Long 1936.

* The Fortescue Candle (n.) Long 1936.

** Tread Softly (n.) Long 1937.

* Cold Evil (n.) Long 1938.

* The Ebony Stag (n.) Long 1938.

** Black Edged (n.) Long 1939.

* The Case of the Faithful Heart (n.) Long 1939.

* The Case of the Painted Ladies (n.) Long 1940.

* They Never Came Back (n.) Long 1940.

* Such Bright Disguises (n.) Long 1941.

* Glittering Prizes (n.) Long 1942.

* Reverse the Charges (n.) Long 1943.

* The Grim Maiden (n.) Long 1944.

* The Case of Elymas the Sorcerer (n.) Long 1945.

* Conspiracy at Angel (n.) Long 1947.

* Exit Sir John (n.) Long 1947.

* The Sharp Quillet (n.) Long 1947.

* The Swinging Death (n.) Long 1948.

* Men for Pieces (n.) Long 1949.

* Black Agent (n.) Long 1950.

* And Cauldron Bubble (n.) Long 1951.

* Where There Was Smoke (n.) Long 1951.

* The Ring of Innocent (n.) Long 1952.

* The Running Nun (n.) Long 1952.

* The Seventh Sign (n.) Long 1952.

* Out of the Dusk (n.) Long 1953.

* The Doll’s Done Dancing (n.) Long 1954.

* The Feet of Death (n.) Long 1954.

* The Mirador Collection (n.) Long 1955.

* The Shaking Spear (n.) Long 1955.

* The Dice Are Dark (n.) Long 1956.

* The Toy Lamb (n.) Long 1956.

* The Hands of Justice (n.) Long 1957.

* The Wife Who Disappeared (n.) Long 1957.

* The Nine Cuts (n.) Long 1958.

* The Saints Are Sinister (n.) Long 1958.

It certainly isn’t likely to mean anything, but Mr. Flynn didn’t do anything like slow down toward the end of his writing career, did he? Sixteen books between 1951 and 1958, after reaching the age of 66. One might guess that he’d retired from his day job (see above).

Heading off to see what Google says, with the author having such a common name, it was quickly discovered that any kind of effective search was going to have to be done on Bathurst the character, rather than Brian Flynn the author. And — there’s nothing to be found. All that comes up are books by Flynn for sale from various dealers’ catalogues. Other than what Al Hubin has provided for him in his entry in CFIV, there’s not a single website providing information on either author or character to be found, not one citation, nothing. (That’s about to change, however, isn’t it?)

Obviously Brian Flynn was no rival to Agatha Christie, but why has he so drastically dropped out of sight? Were his books so indifferently or badly written? On the basis of one example, I’d say no, but on the basis of the very same example, I’d have to agree (if asked) that the style of story is outdated, or at least its ending is. The detective work is essentially sound, although the reader is not made privy to all that Anthony Bathurst knows.

And I see that I’m writing this review wrong end to, and so to right this wrong, let me jump back to the prologue, in which a defendant in court is sentenced to die (and does), but so does the entire jury, all twelve individuals, wiped out in a rocket bomb attack and preceding the defendant to death. I don’t think I’ve ever read that in a book before!

At some length of time later, more deaths begin occurring, the first being that of Nicholas Flagon, a justice on the panel that denied the appeal of the defendant in the prologue. Which is why I so strongly dislike prologues, if I may bring this small rant out into the open one more time. I hate knowing facts and information that the detectives on the case do not have. I don’t enjoy it, I don’t like watching bright policeman and even brighter private detectives work their way through investigations on a case that doesn’t really begin (for me) until they’ve caught up to where I already am, due to the wisdom imparted to me when I didn’t really want it.

End of rant. Dr. Harradine and the local Inspector, a man named Catchpole, are the first on the scene. Tied around the shaft of the dart that has just killed its victim is a slip of paper that says, “A nice sharp quillet. Ay!”

Off to the dictionary go I, and wouldn’t you? A quillet is not a small pen, as suggested on page 30, but: “An evasion. In French ‘pleadings’ each separate allegation in the plaintiff’s charge, and every distinct plea in the defendant’s answer used to begin with qu’il est; whence our quillet, to signify a false charge, or an evasive answer.” Emphasis on “a false charge.”

The policemen on the case, and Anthony Bathurst, do not get back to this point until page 111, so OK, I did some investigating on my own and learned something before they did. I’m not contradicting myself, in terms of what I said about prologues just moments before. I think that this is acceptable, isn’t it?

As for Anthony Lotherington Bathurst, he enters the scene on page 50, when he’s asked by Commissioner Kemble of Scotland Yard to add his expertise to the men on the ground (so to speak) where the victim was killed, their efforts seemingly going nowhere. Bathurst agrees — there’s nothing like a good solid case of mystery to work on — and together with Chief Detective-Inspector MacMorran he makes his way to the otherwise sleepy village of Quiddington St. Phillip, just in time for another death to have occurred.

From this you may thinking that Bathurst is just another policeman highly regarded for solving crimes, but he is not. He’s a private detective. PI’s in the US have seldom had this kind of respect for their abilities as those who plied their trade in England. Perhaps Bathurst should be called a private inquiry agent, along the lines of a Sherlock Holmes. The name of the profession makes all of the difference in the world.

By page 113 Bathurst has decided that he knows who the killer is, but (of course) he has no proof. On page 174 he explains, but he fudges a little, in my opinion, for back on page 113, as he relates it later, all he had were the same four suspects that the reader had, with only a high probability as to which of the four it was likely to be.

Coming in between is a matter of filling in of the details, plus a long stretch of about 25 pages’ worth of unadulterated thriller-like behavior in which the next projected victim of the killer must be protected and the reader (literally) comes along only for the ride. Which is to say that if the reader were kept informed of what is happening, he (or she) would also know who it was the victim is being protected against.

If that makes any sense at all. In any case, everything works out fine, and handshakes all around are the order of day. While Flynn was no rival to Christie or any of the other names you’re a lot more familiar with, in my opinion neither does he deserve to be forgotten. There are some scenes in this book, well-described, that will linger in memory for a while, including the prologue, and yes, I’d read another adventure of Mr. Bathurst at any place and time that you say, other than the break of dawn.

— January 2007