MORTON WOLSON – The Nightmare Blonde

Pocket, paperback original; 1st printing, April 1988.

This book escaped a lot of notice when it came out, or at least that’s what I strongly suspect. Reading just the cover and the blurb at the top – “It was murder. A Hatchet Job.” – I think the average reader would have thought that this was just another horror novel of the blood and gore variety, both of which were very popular at the time. Nor would the name of the author have meant anything to anybody.

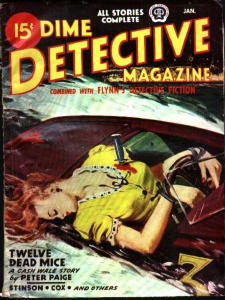

But what if I told you that Morton Wolson was the real name of 1940s pulp writer Peter Paige, creator of the private detective Cash Wale? Or at least I think that Wale was a PI, but I may be wrong and someone will have to tell me.

In any case, Peter Paige wrote a slew of detective stories for magazines like Black Mask, Detective Fiction Weekly and Dime Detective – mostly the latter, I believe – until disappearing from sight about the same time as most of the pulps died, in the early 1950s. Most of them were, by all accounts, fairly ordinary. Paige is a not a name which comes to many people’s mind when it comes to pulp detective fiction. Myself, I know the name, and I know Cash Wale, his primary series character, but as far as any single story is concerned, I can’t think of a single plot line, I have to say, and reluctantly so as I do.

When I asked veteran researcher Victor Berch to see what he could come up with as far as either Paige or Wolson was concerned, he did his usual amazing sleight-of-hand and came up with a couple of interesting items. In the Los Angeles Times of January 7, 1946, there was a short item with the following headline: Writer, Held for Beating Wife, Says She Beat Him:

Morton Wolson, 32, detective story writer under the name of Peter Paige, was in the San Pedro Jail yesterday facing a charge of wife beating… Mrs. Wolson [Ruth, age 23] charged that he husband struck her in the face during an argument… Wolson, in jail … denied the charges and declared that he was merely trying to defend himself.

Accompanying the article, not much longer than the excerpt above, are separate photos of both Wolson and his wife, who is shown feeding their baby with a bottle. (The headline of the item that follows on the same page is: Jeanne Crain and Mother Reconciled.)

Besides the work he did for the pulps as Peter Paige, Wolson had two stories published under his own name. The first one appeared in the January 1954 issue of EQMM, a tale entitled “The Attacker,” and a little bit later, “The Glass Room,” was published in the September 1957 issue.

Wolson’s output may have been small under his own name, but “The Attacker” was good enough to be selected in David C. Cooke’s annual Best Detective Stories of the Year anthology for 1954, and more than that, to be picked up again by Allen J. Hubin’s Best of the Best Detective Stories: 25th Anniversary Collection in 1971. (Al did not remember this fact while he and I were corresponding a short while ago about Wolson, until I pointed it out to him.)

There is one entry for Wolson on www.imdb.com. A story he wrote was the basis for “Prime Suspect,” an episode of Jane Wyman Presents the Fireside Theater, telecast on 27 February 1958. A gent named Steve Fisher did the adaptation, and an actress named Nita Talbot appeared in it, whom I thought was tremendously good-looking at the time; the leading role was played by William Bendix, whom hardly anybody thought was good-looking at any time. Where the story may have been published earlier remains unknown.

The next time Victor came across Wolson’s name in a newspaper was in the New York Times for March 29, 1970, in an advertisement for a special “Manager’s” sale being held by Furniture-in-the-Raw, an outfit with five stores in the New York City area. I’ll quote the relevant detail:

Our Queens store mgr. Morton Wolson says “If it doesn’t sell at these prices it can’t be sold.”

Nothing more seems to have put Wolson in the news or in any sort of spotlight until the publication of The Nightmare Blonde in 1988, and then, as I alluded to earlier, the book seems to have come and gone without much notice. At the moment there seems to be two copies available on the Internet, one from Alibris in the $3.00 range, and one from England in the $30 range. It is dedicated to his wife Gaye, so it is clear that the earlier one did not last.

But before getting to the main event, perhaps you’ve started to wonder. Wolson was born in 1913 (making his age as reported in the LA Times correct), and he died in 2003. You also may be beginning to wonder about this book he wrote in 1988, when he was 75, and whether it is any good or not.

My answer, in a word, is “yes,” but if I may, I’d also have to say that it’s a qualified response, and I’ll get to that soon. Remember now that it was marketed as a horror novel, which in a strong but not overpowering sense it is, as the murder to be solved is that of a family of four, killed by someone with a very sharp axe.

But what it really, really is, when you really get down to it, is a detective novel in a very traditional sense. It’s also a tough, middle-class sort of novel, and hard-boiled at about the same level as, for example, a Ross Macdonald novel, not to forget to mention that it’s quite definitely noirish in a way as well.

Let me explain that last sentence right away. Dan Warden, the leading character, is the former chief of police in Oregon City, a town somewhere along the Pacific Ocean where the story takes place, who had recently been fired for beating up a newspaper columnist’s nephew and being chewed out in print by that very same newspaper columnist. After coming out of a 24-hour drinking binge, about which he remembers nothing, he discovers that it is (no surprise here) the newspaper columnist who has been murdered, along with the three remaining members of his family.

Which makes Dan Warden the number one suspect, no matter how close his friendship with the police commissioner is. At the same time as Warden is discovering how badly his life has been suddenly turned upside down and inside out, he makes a friend – saving her life, to be precise, as she (a blonde) tries jumping off the end of Fisherman’s Wharf, but miscalculating badly as she does so. Allow me to insert a long quote right about here, taken from pages 17 and 18:

“I’m really all right,” she said. “The problem was not being able to talk it out. There was nobody I could really talk to. I had to keep it inside me. Like a nightmare that wouldn’t leave me alone. Do you know what I’m trying to say?”

“Sure,” Dan said, his arm around her waist, urging her along. For the first time he realized that she had a slender, almost lithe, waist, and he felt a tug of sexual excitement, followed by a flush of shame that he should even note such a thing in this vulnerable woman. “I know,” he said. “It’s like you couldn’t get out of the mirror.”

They were moving very slowly. She put her face against his chest and through the fabric said, “Do you know what it’s like to be two people? I mean two separate people — and one doesn’t know what the other is thinking or doing except in dreams now and then, and you don’t understand the dreams?”

“I know all about it,” he told the droplets in her blond hair.

Her eyes probed his.

“Don’t joke with me, please!”

“Scout’s honor,” he said, urging her toward Bayfront Street. “Me, I just had a twenty-four hour memory gap. And while I can remember staring at myself in a lot of bar mirrors, and awakening once on a strange back porch the other side of town, and seeing a sudden blinding flash of light, and walking several hundred miles through this rain, I have no idea where I left my hat or coat or parked my Chevy, or who I punched, or who punched and scratched me. I have not even the dimmest idea of even seeing the man I’m supposed to have either punched to death or killed with a hatchet.”

Kay Mullins (that’s her name) has had psychological problems dealing with children in the past, and now two of them are dead, and the reason for emphasizing that she is a blonde, as I did a just a moment ago, is that several blonde hairs have been found at the scene of the murders.

It takes Dan most of the rest of the book to investigate the crimes while trying to stay ahead of the new police chief, who still considers him to be his primary suspect, while keeping Kay stable and discovering just how many blondes just happened to be in and around the area of the victims’ home, including Kay herself.

Part of the investigation includes visiting a camp of the local branch of the White Knights of America and at least three brothels of increasing degrees of sophistication, and some low spots as well. It’s a tough, rough story at times, and while it tends to start rambling a little, it still provides about four hours of pure entertainment, or at least it did for me, flawed only – here comes a qualifier – by the inescapable unlikelihood of one too many fairly uncommon events, all happening at the same time and in the same place.

But while the laws of probabilities, still enforced in every state in the union, say that the juxtaposition of so many blondes in one focal point of chaos, could not and should not have happened, what Wolson does is not easy. He makes the book flow well enough, and smoothly enough, that you (the reader) don’t (and can’t) stop to think about it while you’re in the process of reading, and read it you will.

As the identity of the killer becomes increasingly clear, and Wolson does a more than creditable job in disguising the solution to the murders for as long as he can – and even longer than he had a right to, truth be said – the chills begin as well, intellectually as well as (without trying to give anything away) deep down inside the reader’s bones somewhere.

Nor is the book over even then. For noir fans everywhere, lift a glass to a pulp writer past. This one’s for you.

— written in September 2006

UPDATE: Victor Berch has come up with some more information on Wolson’s life. Why don’t I simply let him have the floor:

“About the only thing I can add are some vital statistics: Morton Wolson was born the son of Joseph and Zina Wolson on June 9, 1913 in New York. He died January 4, 2003 in Laguna Hills, CA. Might have been living in Mission Viejo as that seems to be the latest phone record. At the time of his death, he was married to a woman named Gaye (last maiden name unknown). She was born February 1, 1927 and died Aug 30, 2005. It is highly possible that Morton was not his original name as he is listed in the 1920 US Census as Mortimer. He may have thought that was too sissified of a name and decided to call himself Morton, which is the name he used for Social Security purposes. Oh, his parents were immigrants from Russia. He also had a brother, Robert.”