Mon 29 Apr 2019

A Movie! Book!! Review by Dan Stumpf: THE BIG LEBOWSKI (1998) / ADAM BERTOCCI – Two Gentlemen of Lebowski.

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[10] Comments

THE BIG LEBOWSKI. Polygram, 1998. Jeff Bridges, John Goodman, Julianne Moore, Steve Buscemi, David Huddleston, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Tara Reid, John Turturro, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazarra, and Jon Polito. Written & directed by Joel & Ethan Coen.

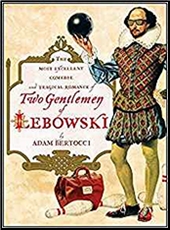

ADAM BERTOCCI – Two Gentlemen of Lebowski: A Most Excellent Comedie and Tragical Romance. Simon & Schuster, trade paperback, 2010.

Okay, so this time it’s a movie and the book inspired by it – or as Adam Bertocci would have it, the text of the play Shakespeare wrote after seeing it. Got that?

At this point there’s really no use going into a detailed synopsis or critique of The Big Lebowkski. It’s a cult film, which means you either love it or can’t imagine why anyone would. There’s enough lawlessness, detection and mayhem to qualify it for anyone’s list of crime films, but suffused throughout with so much deliberate quirkiness that the question of Whodunit seems completely irrelevant.

What strikes me about Lebowski though, is its compelling similarity to Robert Altman’s film of The Long Goodbye (UA/Lions Gate, 1973). Besides the obvious L.A. ambiance, both films feature protagonists seriously out of step with the world they inhabit, cast into convoluted plots which they — and we (and, I suspect, the writers) — only partly comprehend, adrift in an ocean of whackos, weirdoes and certified wing nuts, dancing with sudden death like a monkey on a high wire. Mark Rydell in Goodbye has Ben Gazarra as his counterpart in Lebowski, just as Sterling Hayden in the earlier film is mirrored by David Huiddleston in the later one. It’s as if the Coens saw Altman’s screwy classic when they were impressionable teens and never got over it.

Like I say, there’s been enough written about this film already, but I want to make note of the pitch-perfect performances of Philip Seymour Hoffman as an unflappable toady and John Turturro doing a dead-on impression of Timothy Carey as a mad bowler. Add Steve Buscemi as the kegler equivalent of Elisha Cook Jr, and you have an able supporting cast indeed — all blown off the screen by John Goodman’s perennial Nam Vet, Walter.

More than a decade after Lebowksi hit the screens, Adam Bertocci wondered in print what The Big Lebowski would have been like if written by the Bard of Avon. He even went so far as to write an afterword, detailing how Shakespeare might have seen someone else’s Elizabethan play of the story and stolen it (as playwrights of his time were wont to do—leading to flocks of Angry Bards) for his own Two Gentlemen of Lebowski.

I should say up front that this will appeal mainly to those who have some familiarity with the works we call Shakespeare’s. When Sam Elliott (I forgot to mention him, didn’t I?) says “Sometimes you get the Bear†one doesn’t automatically recall the stage direction from Winter’s Tale, “Exit, pursued by a bear.†But Bertocci does.

It will be lost on some. As will many (most?) of the other allusions. But no one should miss the author’s seriocomic “footnotes†explaining things like Cracked Cheeks (“Maps of the period depicted wind in the form of clouds blowing over the land and possibly on freshly-painted toes.â€) and Haters of Jewry (“Anti-semites. In Elizabethan England, a synonym for ‘everyone’.â€)

Cult items to be sure. Take them for all in all, we most likely shall not look upon their like again. But we can hope.