Tue 26 Aug 2008

THE LONG WAIT. United Artists, 1954. Anthony Quinn, Peggie Castle, Gene Evans, Mary Ellen Kay, Shawn Smith, Dolores Donlon, Charles Coburn. Based on the novel by Mickey Spillane. Director: Victor Saville.

In a comment that he left following my review of the movie The Guilty, based on the novelette “He Looked Like Murder,” Walker Martin commended me on comparing and contrasting the film version with Cornell Woolrich’s original story.

I wish I could always do it, but usually it doesn’t work out that way. If I’ve just seen the movie, the book is nowhere to be found. If I’ve just read the book, finding a copy of the film is another question altogether.

Case in point, and another small confession. If I’ve ever read The Long Wait as a novel, it was so long ago (50 years maybe) that if I did, I’ve forgotten it. And if I did read it, the other voice in my head says, how could I have possibly forgotten it?

This last statement was prompted by the post that appeared just before this one. If I ever read a book anything like the one Bill Crider talks about, I think it would have stuck in my memory forever.

Not being able to find my own copy of The Long Wait, I thought that Bill’s review would serve the purpose almost as well. Probably better, but I won’t tell him that.

But before I being telling you about the movie, you might want to take a look at a short clip of the movie I found on YouTube. It’s the opening few minutes, in which you see Anthony Quinn being picked up as a hitchhiker, the fiery accident that follows, and a brief glimpse of the next scene, with Quinn in a hospital with his hands completely bandaged.

He also has amnesia and no idea of who he is, where he was going, and more importantly, where he was coming from. A prankster, though, with hardly the best intentions in mind, sends him back to Lyncastle, where he’s known as Johnny McBride – and where also a wanted poster proclaims him wanted for murder.

If you read Bill’s review again, you’ll get the idea that the book runs generally along the same lines. I don’t see Anthony Quinn as a “Johnny McBride,” however. His face and that name simply don’t match. I don’t say that he’s miscast, exactly, but I also don’t see him as the girl magnet he becomes as soon as he returns back to Lyncastle. (The police, by the way, have a problem matching him up with their fingerprint evidence. Due to the accident he was in, he no longer has fingerprints.)

In any case, from here on in, I’ll be reviewing the movie, not the book. There is more actual violence in this film than in most noirs – with one early scene standing out in particular, when McBride is trussed up and about to be thrown into a 200-foot-deep quarry, and ends up alive – and the three hoodlums all dead.

And another one later which has to be seen to be believed – and I’ll get back to that later. There is also an elaborate detective story going on as well, or actually a pair of them. First of all, the question is, who’s the real killer? But the second, and the more interesting, is who of the four woman who McBride becomes involved with is his old girl friend, Vera West?

McBride’s memory is gone, of course, and since Vera’s had plastic surgery done before she came back, no one else knows who she is either. Well, one man knows, but he’s killed, shot to death early on. Working against McBride all the way is Servo (Gene Evans), the gangster who practically owns the town. (Evans was last seen by me as the leader of the pack of thieves doggedly hounding the trail of Clint Walker and Roger Moore in Gold of the Seven Saints, reviewed here back in July.)

You do have allow some license to the screenwriter in working all of this into a sensible plot, let alone go down smoothly. (My copy of the film is unfortunately one that originally had color commercials for a California used car dealer in it, and whoever cut them out did not do a very good job of it. Some transitions are jarring, and I am slightly suspicious of them, thinking that maybe some small bits and pieces have been removed.)

There is one long scene in this movie that makes definitely worth watching, even if all you can find is a crummy copy. That’s the one that comes toward the end, with Quinn as McBride tied in a chair in the middle of an empty warehouse, and Peggy Castle as Venus (one of the possible Vera’s) with her feet bound and her hands tied in front of her as she works herself slowly across the floor to him on her elbows, with Servo laughing and deriding her efforts the entire way.

Beautifully photographed in glorious black-and-white, with lots of deep shadows and contrasting areas of light, this is a scene that will stick in your mind for a long time. The movie’s hard to find copies of, but it does exist. It has some flaws, but I hope I’ve made you want to see it. I don’t think you’ll regret it.

PostScript: I sent an advance copy of this review to the previously mentioned Mr. Crider, hoping to come full circle, if possible, and let him compare the film (unseen by him) with the book. His reply, short but succinct: “The quarry scene’s in the novel, and the scene you mention at the end is (probably) much more violent in the novel, a real torture scene.”

I don’t know about you, but I think I’m going to have to find a copy of the book, and soon.

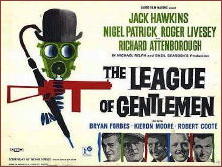

THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN. Allied Film Makers / J. Arthur Rank. 1960. Jack Hawkins, Nigel Patrick, Roger Livesey, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, Kieron Moore, Terence Alexander, Norman Bird, with Robert Coote, Nanette Newman & Oliver Reed (the latter uncredited). Screenplay: Brian Forbes; based on the novel of the same name by John Boland. Director: Basil Dearden.

THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN. Allied Film Makers / J. Arthur Rank. 1960. Jack Hawkins, Nigel Patrick, Roger Livesey, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, Kieron Moore, Terence Alexander, Norman Bird, with Robert Coote, Nanette Newman & Oliver Reed (the latter uncredited). Screenplay: Brian Forbes; based on the novel of the same name by John Boland. Director: Basil Dearden.