Sat 7 Jun 2008

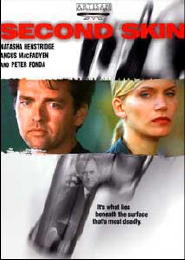

SECOND SKIN. 2000. Natasha Henstridge, Angus Macfadyen, Liam Waite, Peter Fonda. Directed by Darrell James Roodt.

Opening scene: the front of a shabby-looking bookstore, in what is apparently a small Californian beach town. A stunning blonde approaches, enters. From inside, as the owner looks up, her thin white dress is nearly translucent in the sunlight.

She’s looking for a job, but he – a dissheveled-looking fellow not dissimilar to all of the semi-seedy bookstore owners of every shop you’ve ever been in, right? – he doesn’t know that yet. She browses the shelves. “You’ve got some original editions, here,” she says. “Hammett, Thompson, Cain. That’s a nice collection.

“Some of the new ones are good, too,” she goes on, having waited in vain for a response more expressive than a shrug. “Ellroy, Block, Kent Harrington.” The bookstore guy doesn’t recognize the last one. “Who’s that?”

“Dia de Los Muertos,” she murmurs. “The Day of the Dead.”

What an opening! You won’t be able to see the whole scene without finding a copy of the movie on DVD – not difficult to do – but you can see part of it in the trailer for the film. Go here, but please come back.

Why there is a trailer made for a movie that was never released to the theaters, I’m not sure, but maybe for cable TV? It’s a pretty good representation of the film, too, although most of the violence that’s in the film is shown in this short teaser – but not all.

It seems that Crystal Ball – that’s her name, played to icy perfection by former model Natasha Henstridge – is new in town, has no friends, and business is so bad for Sam Kane – that’s his name, played to rumpled perfection by Irish actor Angus Macfadyen – that doesn’t need anybody to work for him. Intrigued, however, he takes her address and phone number …

… and as she is standing outside his shop as she is leaving, she’s hit by a car, by a hit-and-run driver who doesn’t stop. When she wakes up in the hospital, Sam standing by, she does not remember him, does not remember anything. Amnesia.

It seems she has some secrets. Visiting her place on the beach, Sam finds a gun under her pillow. Someone is also following her trail, a nasty piece of work named Tommy G (Liam Waite) complete with tattoos and nifty knack with both guns and knives. Meanwhile, Sam has his own problems and his own secrets. Plagued by a blackmailer, he …

Hold on, hold on. Too much story. If you’ve read this review this far, you’ll want to watch this movie yourself. Beautifully photographed, this neat little neo-noir tale of crime, secrets and surprises sometimes goes over the top, and in general may try just a little too much, but sometimes excesses with the right kind of intentions can be forgiven.

I did, at least, and I do recommend the movie to you. Most of the people commenting on IMDB didn’t know what to make of the film. Too many cliches, they say, and they may be right, but for me, they’re the right kind of cliches. For me, I might say that the film is a little too violent – and there is one cliche it definitely does not include. Most crime thrillers like this make it seem all too easy to kill someone with only your bare hands and a belt. This one does not.

Getting back to the people commenting on IMDB. They did not like the ending all that much. Obviously knowing the cliches of neo-noir films like this one sadly does not mean that they know what neo-noir films are all about – what on earth does noir mean? – and the ending of this one is a beauty.

Some of them also claim that the ending came from nowhere. Obviously they were not watching all the way through, as I certainly knew that something was happening that was not immediately explained – and I readily confess that I did not know exactly what – and the ending, a near perfect one, came as no surprise to me. (Well, just a little.)

I do not know why films like this are not shown in theaters anymore – well, actually I do. Nobody would come to see them. There must be money to be made, though, in making them and releasing them only on DVD and cable TV, and relying on the fact that word of mouth will catch up to them and a profitable time will be had by all. I hope so.

Using a line that I’ve closed many a movie review with before, if this sounds like your kind of movie, it is.