Tue 2 Oct 2012

A Western Book! Movie!! Review by Dan Stumpf: SHOWDOWN CREEK / FURY AT SHOWDOWN (1957).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western Fiction , Western movies[22] Comments

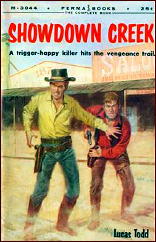

LUCAS TODD – Showdown Creek. Macmillan, hardcover, 1955. Toronto Star Weekly Novel, newspaper supplement, Saturday 19 November 1955. Permabook M-3044, paperback, 1956

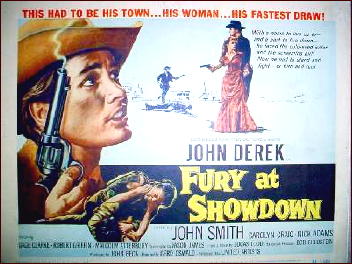

FURY AT SHOWDOWN. United Artists, 1957. John Derek, John Smith, Carolyn Craig, Nick Adams, Gage Clarke, Robert Griffin. Screenplay: Jason James, based on the novel Showdown Creek, by Lucas Todd. Director: Gerd Oswald.

Showdown Creek is the kind of spare, gritty tale that Westerns should aspire to. Researching this, I can find no other book attributed to Lucas Todd, the author, nor any bio/bibliographic background on him, but perhaps that’s as it should be for a book that celebrates the outcast as this once does.

As the story opens, Brock Mitchell is trying to ramrod a one-horse ranch for his broken-legged Uncle Ben and live down a reputation as a smart-ass hellion. Uncle Ben has arranged financing to get him through lean times, but the deal’s hit a snag, and nobody seems to know what the delay is —- until Mitchell learns that Chad Deasey, an ex-con with a grudge against him, has hit town and put up a respectable front, tied in with the most prominent local lawyer (soon to turn up dead) and persuaded the town banker to put the brakes on Uncle Ben’s deal, apparently just to ruin him and repay Mitchell for killing Deasey’s brother in a fair fight back in Brock’s gun-toting days.

It’s pretty standard stuff for a Western: crooked banker, shady lawyer, upright hero handy with a gun, honest ranchers and even a purty blue-eyed widder woman trying to understand it all. Author Todd seems to know something about moving cattle around (not all western writers do) and he puts it across as he ladles out the more standard ingredients into his prairie stew, giving Peters a hot-headed sidekick and adding something about the railroad coming through.

But he also tinges all this with an almost intangible feel for the dilemma of a flawed man painfully misunderstood. Every fight, shoot-out and unsolved crime echoes not only in physical violence but also in the looks Brock gets from the good citizens of Showdown Creek: the rumors, conversations broken off when he enters a room, and his increasing isolation from a community he needs.

It’s intriguing stuff, and if it never quite rises to the level of Camus, the sense of alienation is still strong enough to lift this above the run-of-the-range shoot-’em-down and linger in the memory.

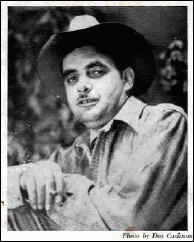

Showdown Creek was filmed, appropriately enough, by Gerd Oswald, himself something of a Hollywood pariah, who was given only five days and a cast of unknowns and no-talents to do the job —- the only two players you ever heard of in this movie are John Derek and Nick Adams, so you see what I mean about the acting.

The marvel is that Fury at Showdown emerges as a tight, deeply-felt tale of guns, cattle and youthful angst.

Given the low budget and tight schedule, Fury at Showdown is necessarily a town-bound western, rarely leaving the claustrophobic confines of office, saloon and jail for the free range that now seems more like a false promise than the reality of the West.

Somehow, though, that only helps convey the sense of constriction felt by the hero (or supposedly felt; this is John Derek acting, remember) as he struggles to reach some wide open plain of the soul, free of the town’s censure.

That sounds like tall boots for a B Western to fill, but writer Jason James tweaks the story significantly — in his version, Chad Deasey has always been a respectable citizen and it’s Brock Mitchell who’s the ex-con, just released from jail for killing Deasey’s brother — and director Gerd Oswald puts it across with well-judged camera work and a sense of pace that never falters.

Fury at Showdown never got much attention, and it’s far from ideal, but definitely worth your time.