Wed 22 Dec 2010

A Western Review by Dan Stumpf: DONALD HAMILTON – Smoky Valley (Book and Film).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western Fiction , Western moviesNo Comments

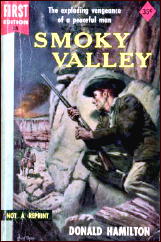

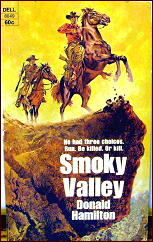

DONALD HAMILTON – Smoky Valley. Dell First Edition #18, paperback original; reprinted several times, first by Dell, then Fawcett Gold Medal.

◠THE VIOLENT MEN. Columbia, 1955. Glenn Ford, Barbara Stanwyck, Edward G. Robinson, Dianne Foster, Brian Keith. Based on the novel Smoky Valley by Donald Hamilton. Director: Rudolph Maté.

A while ago on this blog I mentioned a pleasing little Western called The Violent Men (Columbia, 1955), and last month I managed to seek out the book it was based on, Smoky Valley, by none other than Donald Hamilton.

It turned out to be a fun read, and no less interesting to see how it was re-jiggered for the movie.

Smoky Valley tells the brief story of John Parrish, a broken Civil War vet come west for his health, and it picks up just as the neighbors who nursed him to recovery are being forced off their land by a nasty rancher and his nastier son-in-law, who own that icon of the genre, The Biggest Spread In The Valley, and mean to make it bigger.

In the way of Western good-guys, Parrish avoids conflict as long as possible and even eats a certain amount of dirt before striking back with that cool, deadly efficiency a writer like Hamilton puts across so well.

Indeed, it’s Hamilton’s quiet-but-deadly prose that lifts this thing out of the ordinary. Hamilton knew about guns, horses and men, and he could structure a story to show off his skill with them.

This was translated very ably to the screen in the movie; one particularly remembers Brian Keith casually loading his gun while everyone else talks about settling this thing peaceably, or Parrish (Glenn Ford) coolly murdering a gunman — both scenes straight from Hamilton’s book, tautly written and ably filmed.

But the main difference between page and screen is Barbara Stanwyck. I don’t know what led Columbia to put Stanwyck in this film. Her character doesn’t appear in the book, but once she was in it, they had to build up a good part for her.

And they sure did. Playing the cattle baron’s dissatisfied trophy wife (starring again with Edward G. Robinson ten years after Double Indemnity) she projects her dominant personality against a back-drop worthy of her, somehow without overbalancing the story. Neat trick, that.

We still get the basic elements and the full flavor of Hamilton’s tight little novel, with the added attraction of a fine actress at her bitchiest, particularly in a definitive moment when she shows her love for her crippled husband by throwing his crutches in the fire as hes trying to escape a burning house.