REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

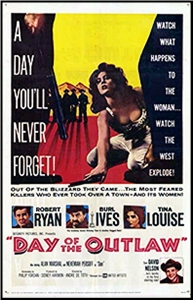

CHARLES O. LOCKE – The Hell Bent Kid. W. W. Norton, hardcover, 1958. Popular Library, paperback, 1958; reprinted. 1963. Ace, paperback, date unknown. Named at one time as one of the top 25 Western novels of all time by the Western Writers of America. Film: Released as From Hell to Texas (20th Century Fox, 1958) Don Murray, Diane Varsi, Chill Wills, R. G. Armstrong, Dennis Hopper. Directed by Henry Hathaway.

This Kid — Tot Lohman — was no murderer and was not penned up. He knew he had to stay on the place, the way I had fixed it with the sheriff. Also, he had killed Shorty Boyd in self-defense, although I think he made a mistake in not saying how it was done. The Boyds said Shorty had been shot. Lohman let it go that way. There was supposed to be more honor to it, if it involved a bullet. On both sides.

When Tot Lohman was probated to me, he had one thing on his mind. His family had been pretty well wiped out, except one brother and his father, who suddenly took consumption and seemed to be dying a slow death. The father, who had been a fine peace officer, pulled up stakes and went into the territory of New Mexico, looking like a skeleton that walked and leaving his son in Texas, which led to the shooting, if it was a shooting, that landed the boy on me.

Tot Lohman is only about eighteen, a fair hand with cattle, but gifted with his two loves, horses and guns. He’s a decent kid, hard luck, but hard luck isn’t unusual on the Staked Plains of West Texas, the Llano Estacado.

But life has just spun out of control for Tot because he killed a Boyd, and the Boyd was related to Hunter Boyd, and his son wild Tom Boyd, and neither will stand for the killing.

Tot wisely decides getting out of the country will be better than waiting for the Boyds. He heads for New Mexico looking for his father determined to put the Boyds behind him, but the Boyds are determined and want “justice,†and they will do anything to get it, including turning Tot Lohman, a big kid who just happens to be good with a gun into the Hell Bent Kid, a killer with a conscience and a growing list of white crosses in his wake.

I have a taste for Westerns, and bend to no one in my love of the more common pulp Western from Zane Gray to Louis L’Amour and the men and women who write them, but there is another kind of Western, the more literary model, the Western as novel, and not just story that I admire. It is no attack on the former to admire the latter.

It’s a sub-genre of the more popular form with a history in itself with familiar names like Owen Wister, Eugene Manlove Rhodes, Walter Van Tilberg Clark, Frederick Manfred, Dorothy Johnson, Wallace Stegner, Conrad Richter, Oakley Hall, Larry McMurtry, Cormac McCarthy, and now one I never knew about before, Charles O. Locke. Titles like The Oxbow Incident, The King of Spades, A Man Called Horse, Sea of Grass, Shane, The Last Hunt, Warlock, Blood Meridian, and Lonesome Dove are among its more famous examples.

As you might imagine, it’s rarer to discover a book in this category than in the more familiar form and a time to celebrate when you do.

The Hell Bent Kid is a pure example of the form. The plot may be straight out of a hundred pulp Western fantasies, but this is a novel and not just a tale. It is about the destruction of a young man forced to run and fight through brutal country against hard men who learn too late his almost mystical skill with a gun. It is about a good kid forced to become a killer, a decent young man who doesn’t want to be what his hunters make him into, who meets a girl, has a brief moment of normalcy, and is forced to take up the gun one last time.

“No more of this fooling around with scare-shots and cattle. I will shoot first from now on and will aim for one of two places, the head or the heart.â€

Amos looked at me a long time. “Well,†he finally said, “if you aim at either one, you kill a man as a rule, and you don’t have to prove to me that you can hit where you aim. I hope you get a bagful of Boyds. But in the end they’ll get you. Yep.â€

It’s the inevitability of Tot Lohman’s fate that makes this a novel and not just a well written pulp tale. The same story appeared in a thousand Western pulps and original paperbacks and still does today, but seldom written with the simplicity and human understanding of this version.

It’s no coincidence this one ends in Santa Rosa, New Mexico, though Tot Lohman is no Billy the Kid, and his fate isn’t met at the hands of a Pat Garrett.

After the noise there was dead quiet. The breeze had died. I looked once quick at the faces of the cattlemen and they were a study. Except Hunter who was smiling to himself so that, having known him thirty years, he visibly began to get small in my eyes and once he had seemed pretty big. Yes sir. For as I saw him smile, he seemed to shrivel down to less than a fraction of a man. Hunter couldn’t change. He was still a born winner and could even rake in life’s chips over the body of his dead son. Sometimes it takes a long time and a particular set of circumstances to catch up with a man.

There is no shortage of standard Western thrills here, but there hangs over the book a hint of Greek tragedy, of hard country written on men’s souls, and burned in women’s broken hearts and too short lives. As I said at the beginning I had never heard of this book or of Locke, but now I will look for his name and treasure this book.

Told in epistolary form, a long section in the middle by Tot himself, the book is as easy to read as any Western, it just has a little more to say than most, the difference between a great B Western film and John Ford, between blazing guns and the smell of gunsmoke and the exposed souls of the people involved.

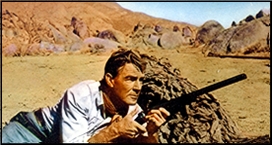

The Hell Bent Kid was made into a decent film in 1958, From Hell To Texas, directed by Henry Hathaway. It’s a pretty good little film aimed at focusing on younger stars, but it is a pale adaptation of the novel, much more a standard Western than the well-written novel this book is.