Sun 24 Mar 2019

A Book! Movie!! Review by Dan Stumpf: ERNEST HAYCOX – Canyon Passage / Film (1946).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western Fiction , Western movies[7] Comments

ERNEST HAYCOX – Canyon Passage. Little Brown, hardcover, 1945. Pocket, #640, paperback, 1949. Many other reprint editions exist.

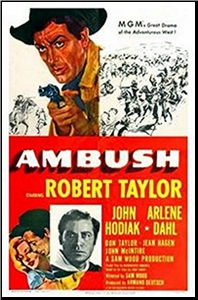

CANYON PASSAGE. Universal, 1946. Dana Andrews, Brian Donlevy, Susan Hayward, Patricia Roc, Ward Bond, Hoagy Carmichael, Lloyd Bridges and Andy Devine. Screenplay by Ernest Pascal, based on the novel by Ernest Haycox. Directed by Jacques Tourneur.

Ernest Haycox writes best about working men — miners, ranchers, or as here a freighter — made heroes by force of circumstance, set in communities that are not always right or just, but keep striving to get that way. Canyon Passage is the best example of this I’ve seen so far, not so much a carefully-plotted story as a series of interactions between fallible people bouncing off each other in an evolving milieu.

A book like this gets life from its characters, and Haycox gives us a colorful cast. Logan Stuart, the central character, is the solid, dependable sort to hang a story on; he has a hankerin’ for smart, tough Lucy Overmire, and she for him, but… well, Haycox puts it best, as Logan ponders to himself:

I credit Haycox with making these ill-turned relationships at least as interesting as the fights, murders and Indian raids that propel the story. He draws an interesting parallel between George Camrose — Logan’s friend betrothed to Lucy, and also a polished thief preying on his friends — and Honey Bragg, a murderous brute and near-outcast, also preying on the locals. Both are eventually punished by the mining camp they live in (and off) but in very different ways, and it’s this sense of Community as Character that gives Canyon Passage real depth.

Bragg gets his comeuppance at the hands of Logan Stuart, after the good people of the town have goaded them into a fight for no better reason than they wanted to see a battle royal. And Haycox writes us a dandy. Faced with the meaner, stronger, Bragg, Stuart starts the fight by cracking a bottle across his face, then smashing a chair over his head, then picking up the pieces of the chair and smashing them over his head, then picking up another chair…. You get the idea. It’s brutal and very real.

Camrose, on the other hand, gets tried by a Miner’s Court for the murder of a man whose poke he’s pilfered, found guilty on the basis of circumstantial evidence (He is in fact guilty as hell.) and locked up till the town can get around to lynching him—which puts Logan in the position of having to rescue his guilty buddy for the sake of the misguided Lucy.

Me, I woulda just sat back, seen him hanged, and moved in on Lucy myself, but that’s probably why I was never the hero of a Western. And I have to say Haycox rings in the Indian Raid that brings everything to a head and resolves the various conflicts without seeming a bit contrived.

Producer Walter Wanger made a fine job of filming this, hiring Jacques Tourneur, known for his horror flicks with Val Lewton, to direct, and dependable hack Ernest Pascal to stick close to the book. He also signed up sturdy leads Andrews, Donlevy and Hayward, and a host of dependable character actors, including Ward Bond as Bragg, Andy Devine as a homesteader, and best of all Hoagy Carmichael as an amiable minstrel.

The result is a film of considerable charm and surprising brutality. Like I say, writer Pascal stays close to the book, and director Tourneur gives us the beatings & killings with unflinching nastiness, done up in fairy-tale Technicolor by photographer Edward (Heaven Can Wait) Cronjager.

There is one point where the movie departs from the book though, and I think it’s an improvement. And since it’s at the ending, I’ll throw in a SPOILER ALERT!!

In the book, Logan Stewart helps his friend Camrose escape, but it does no good as he’s shot down shortly thereafter by one of his victims. Logan, having led the miners against raiding Indians, is forgiven by the town, mainly because they got their man anyway and no real harm done.

In the movie, however, Logan returns from injun-fightin’ to find that the good people of the town have burned down his store as retribution for his crime. Having chastened him, they are now willing to accept him back as a member of society in good standing. And Logan accepts it as a just punishment, ready to move on with his life.

It’s not a major story element, but somehow this moment, as directed by Tourneur, gets to the meat of what Haycox was saying in the book. I’m not sure I can put it into words, but it has something to do with a civilization not built on laws, religion, or even tradition, but on people. And therefore as good or bad as the best and worst of us.

As Walt Kelly used to say, “it’s enough to make a man think.â€