Mon 13 Jul 2009

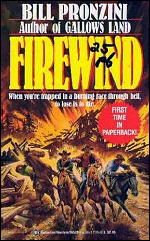

JACK FOXX – Wildfire. Bobbs-Merrill, hardcover, 1978. Reworked and republished as Firewind, as by Bill Pronzini: M. Evans, hardcover, 1989; paperback reprint: Ballantine, 1990.

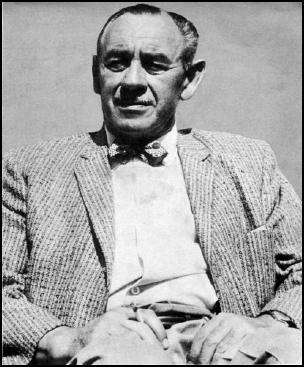

When I recently uncovered my review of Wildfire, by Jack Foxx, and posted it here on the blog, I was surprised to learn that the author, Bill Pronzini, had “reworked” the novel and republished it as Firewind. I don’t think I knew this before, or if I did, I’d forgotten and the fact that there was a second version had vanished from memory.

Now here’s the really strange thing. I could not determine from my review of Wildfire (and could not remember) the time period in which it took place, but I was reasonably sure that it was an present day affair. But when I saw the cover of the paperback edition of Firewind, it was obvious that the latter was an out-and-out western novel. Could I have been wrong about Wildfire?

Nothing on the Internet was of any assistance, nor of course could I find my copy of Wildfire (the first book, in case I’m starting to lose you, which I’d really rather not do). The only solution was to ask the man himself, Bill Pronzini, that is. If he didn’t know, who would?

And of course he did. He’ll take over from here:

Very nice review of Wildfire, which I missed seeing when it first appeared; I’m pleased that you found it to be a suspenseful read. Firewind is a reworking of Wildfire, but not merely a reissue under a different title.

Although the basic storyline and general progression are similar in both versions, Wildfire has a contemporary setting and Firewind a historical one, and the characters and their motives and interactions are different.

I wasn’t satisfied with the way Wildfire turned out, but it wasn’t until a few years after it was published that I realized why: the story works better as a “western” and should have been written as such in the first place.

So when Sara Ann Freed, who was editing M. Evans’ western line in the late 80s, asked me to do a second book for her (after The Last Days of Horse-Shy Halloran), it gave me an opportunity to transform Wildfire into Firewind. The latter is much the better of the two.

As to the Jack Foxx name, which you also asked about, I chose it for two reasons. The minor is that it’s short and punchy, both surname and given name just four letters; the major is that I’ve always considered the letter “X” something of a lucky talisman.

Long-time readers of my work might note that I often give characters names containing an “x”.

Pronzini’s “X” file. One of my many quirks, on and off the printed page.