Fri 6 Dec 2013

A Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: MAN AT LARGE (1941).

Posted by Steve under Action Adventure movies , Reviews[4] Comments

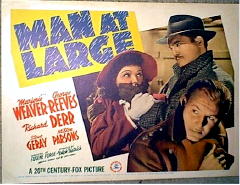

MAN AT LARGE. Fox, 1941. Marjorie Weaver, George Reeves, Richard Derr, Steve Geray, Milton Parsons, Spencer Charters, Lucien Littlefield, Elisha Cook Jr., Minerva Urecal. Director: Eugene Forde.

An un-sung little B-movie that seems at times like an episode of the old Superman TV show, starting off at a great metropolitan newspaper with a grouchy editor, a plucky girl reporter (Marjorie Weaver) and even a visit from George Reeves!

What follows is a tricky, fast-moving and mostly-fun farrago about the search for a fugitive German escapee from a Canadian POW camp (this was made before Pearl Harbor, but the movie doesn’t hesitate to peg the bad guys as Germans) on the run in the US.

Then a surprise as it quickly pivots into a game of cat-und-mouse between the FBI and a nest of spies preying on American cargo ships, who relay their secret messages in pulp-magazine stories written by a Master Spy.

Said spymaster is played by Steven Geray, an actor normally typed as milquetoasts, who seems to have a lot of fun here playing it sinister. And since he’s a writer for the pulps, Geray’s character is naturally a cultured tea-drinking man of affluence, living in a luxury apartment surrounded by servants—like all pulp writers of his day.

Obviously none of this can be taken seriously, and to their credit, Writer John Larkin and director Eugene Forde (both veterans of Fox’s Charlie Chan series) don’t try. Forde directs with an eye for pace, helped out by the photography of Virgil Miller, who heaped atmosphere into Universal’s Sherlock Holmes series and Larkin fills his script with twists and jokes, both surprising and funny.

He also “borrows†heavily from Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps, with our hero suspected of murder after hearing a vital clue gasped out by the victim, a search for a clandestine group known as “The 21 Whistlers†a bit in a noisy music hall, and even some by-play with handcuffs on the hero and heroine.

To Larkin and Forde’s credit though, there’s also a dandy and highly original climax with Reeves and Weaver stalked through a locked apartment by a sharp-shooting blind man.

The result is a film that’s easy to like, and over-and-done-with before you notice it’s gone, considerably enlivened by the playing of Reeves, who looks here like an actor on the verge of stardom, and Ms Weaver, Fox’s all-purpose perky B-movie queen, whose lively thesping never quite lifted her from the low-budget rut — with the astonishing exception of her role as Mary Todd in John Ford’s Young Mr Lincoln.