REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

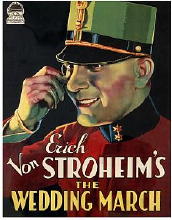

THE WEDDING MARCH. Paramount; 1928. George Fawcett, Maude George, Erich von Stroheim, George Nichols, ZaSu Pitts, Fay Wray. Erich von Stroheim, director; screenplay by von Stroheim and Harry Carr. Photography by Hal Mohr, Buster Sorensen, and Ben Reynolds; art direction by Richard Day and von Stroheim. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

After the cost overruns of The Wedding March and withdrawal of funding before von Stroheim was able to complete Part II as he had planned it, he essentially ended his directing career with Queen Kelly (1929, also incomplete). But what a tribute to his extraordinary skill the first part of The Wedding March is!

Von Stroheim was, of course, popularly known as The Man You Love to Hate, but his role as Prince Nicki von Wildeliebe-Rauffenburg is almost sympathetic. He’s expected to marry properly (that is, a rich wife) but he falls in love with crippled musician Mitzi Schrammell (Fay Wray), much to his (and her) parents’ dismay.

He woos the besmitten Mitzi in a flowered bower where she finally succumbs to his charms, then summarily abandons her when he goes along with his parents’ ambitions (to replenish the family coffers, constantly depleted by the family’s spendthrift ways) and, at the film’s climax, marries Cecelia Schweisser (ZaSu Pitts), the daughter of a wealthy merchant.

The magic of the film (aside from the fine performances) is in von Stroheim’s detailed portrait of an ancient aristocracy largely going to lavish seed, hedonistic and opportunistic, interested only in perpetuating its indolent way of life.

Prince Nicki seems to show some promise of breaking with his class, but if he is to marry a commoner, she must pay for the privilege of marrying him.

Nicki and Mitzi first meet at an elaborate outdoor ceremony where the equestrian Prince is parading with his company in a reel that’s filmed in beautiful two-strip color. If only the quality of the print were as good for the black-and-white sequences that make up most of the cinematography. By the last reel, the print is almost unwatchable, washed out, grainy, with the intertitles unreadable.

One of the Cinevent attendees I was talking to blamed the poor quality on the fact that the print screened was 16mm. My friend Charlie Shibuk has seen a good print of the film and told me that William Everson found his 16mm print to be of quite acceptable quality. It would seem that better prints are available, and I wonder if anyone screened this print before scheduling it.

In addition, the writer of the program notes claims that although von Stroheim began to film part II, the film was taken away from him and given to Josef von Sternberg, who put together a poor version. He further claims that Henri Langlois, of the French Cinematheque, allowed his print to deteriorate.

Charlie has told me that the writer was wrong on both counts. Von Stroheim did, in fact, edit a version of Part II (at the end of which Nicki tries to atone for his rejection of Mitzi), and the French print was destroyed in a fire. So it would seem that the von Stroheim legend endures, a mixture of fanciful fiction and fact.

EDITORIAL COMMENT. For a three-minute glimpse of the wedding march itself — in color — see this YouTube clip.