FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

If you’re interested in Cornell Woolrich and get Turner Classic Movies on satellite, I strongly suggest that, the next time it’s scheduled, you check out Blind Date (Columbia, 1934). It’s not based on anything Woolrich wrote and isn’t even a film noir, but this obscure little gem breathes the spirit of Woolrich’s early non-crime fiction like no other movie I’ve seen.

Ann Sothern stars as a young woman of Manhattan, supporting her parents and a kid brother and sister in the pit of the Depression. As in the country-western song she is torn between two lovers: her steady boyfriend (Paul Kelly), who is “shanty Irish” like herself, and the wealthy young playboy (Neil Hamilton) whom she met on the blind date of the title.

Anyone who’s familiar with the early Woolrich stories, and their recurrent theme that relationships and anguish are inseparable, is sure to feel that this movie must have been based on one of them.

(Homework assignment: read Woolrich’s 1930 tale “Cinderella Magic,” collected in my Love and Night, just before or after watching the movie.)

Even more amazing is the number of links between this film and Woolrich’s future. There’s a short and brutal scene at a dance marathon prefiguring the suspense master’s powerful 1935 tale “Dead on Her Feet.”

Second male lead Paul Kelly was to play the second male lead a dozen years later in the Woolrich-based “Fear in the Night” (1947).

The director, Roy William Neill, would later, and just before his death, helm Black Angel (1946), arguably the finest movie ever based on a Woolrich novel.

Even the title Blind Date figures in the Woolrich canon: first in his pulp story “Blind Date with Death” (1937), later as the new title for the 1935 story better known as “The Corpse and the Kid” and “Boy with Body” when, in 1949, Fred Dannay reprinted it in EQMM.

All these links are coincidences, of course, but what an eye-popping network of them!

Speaking of Fred Dannay, a Japanese film crew will soon be coming to America to make a documentary on Ellery Queen. Since this is the first segment of a projected series to be called The Great Mystery Writers, I assume (and hope) that the emphasis will be on Fred and his first cousin Manny Lee, not on the detective character whose name they chose as their joint byline.

I’m going to be involved in this project but exactly to what extent and in what capacity isn’t clear yet. For updates, stay tuned to this column.

Soon to be published by the ABA Press (that’s ABA as in American Bar Association) is an anthology entitled Lawyers in Your Living Room! which deals, as you must already have guessed, with the countless series about the legal profession that have graced or disgraced our TV screens for more than half a century.

As you also must already have guessed, I wrote the chapter on Perry Mason. There’s also a chapter on The Defenders, but most of the series discussed in the book are much more recent than Mason. For more details you needn’t wait for my next column, just google the title.

During much of the next week my eyes are going to be glued to the PDF of the second volume of The Dark Page, which I am checking over for author Kevin Johnson.

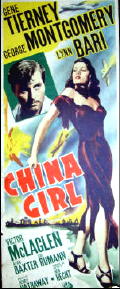

The first volume was a lavish coffee-table book dealing with those films noirs of the 1940s that were based on novels or short stories and with their literary sources.

The sequel covers the noirs of the Fifties and early Sixties and their literary sources, ranging from Dreiser and Hemingway and Graham Greene, through a slew of specialists in noir fiction — Horace McCoy, Steve Fisher, Dorothy B. Hughes, Ed McBain, John D. MacDonald, David Goodis and (need I mention?) Woolrich — to such long-forgotten pen wielders as Ferguson Findley and Willard Wiener.

Mickey Spillane, of course, gets full coverage. The choices of what films count as noir are at times quite unusual: The Bad Seed and the first version of Death of a Salesman are in, as is Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, but Psycho is out.

The illustrations aren’t part of my PDF but, if the first Dark Page volume is any indication, they’ll be stunning.

If you groove on Harry Stephen Keeler, the greatest nut who ever wrote a book, you’ll be pleased to hear that Strands of the Web, a collection that brings together the vast majority of his early short stories — not all because two or three remain lost — is about to be published by Ramble House.

Most of these tales were written between 1913 and 1916, when Keeler was in his early and middle twenties and just beginning to develop the webwork patterns of wild coincidence that were to become his trademark but the earliest story dates back to 1910 and the latest to 1962, a few years before his death.

You’ll find a few foreshadowings of his wacky webs now and then in this collection, but the prose is much more ordinary than the labyrinth sentences he eventually came to favor. The most noticeable influence on these stories is O. Henry, perhaps the most popular American short-fiction writer of all time, who died the same year Keeler first set pen to paper.

For more details, go to www.ramblehouse.com.