Fri 20 Feb 2015

A Sci-Fi Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: ATTACK OF THE ROBOTS (1966).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , SF & Fantasy films[8] Comments

ATTACK OF THE ROBOTS / CARTES SUR TABLE / CARTAS BOCA ARRIBA. Spéva Films / Ciné-Alliance / Hesperia Films S.A., French-Spanish, 1966. Eddie Constantine, Françoise Brion, Fernando Rey, Sophie Hardy. Written by Jean-Claude Carriere. Directed by Jesus Franco….

…which I guess answers the question, “What would Jesus direct?â€

Actually this is a surprisingly light and enjoyable thing to come from Jesus (aka “Jess†for American consumption) Franco, who more typically did sex-and-gore epics like Revenge of the Alligator Ladies and Lust for Frankenstein. It helps that it was written by Jean-Claude Carriere, a frequent collaborator with Luis Bunuel and the screenwriter of such trifles as Borsalino and Viva Maria.

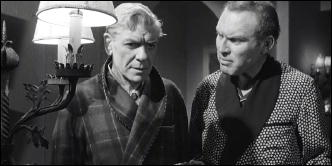

It also helps that Eddie Constantine stars, and lends his compelling screen presence to a role suited perfectly to him. For those of you not in on it, Constantine was an American actor who hit the big time as a night club singer in France and went on to star in a whole bunch of “B†action movies, usually as Lemmy Caution and most famously in Jen-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965).

Here he plays a retired Secret Agent named Al Pereira (or Carl Peterson, depending on the dubbing) called back into the field by his superiors to check out assassinations committed by individuals apparently under the influence of what’s known in the genre as Some Diabolical Mind Control. And he isn’t on the job for much longer than a few bites of popcorn before he’s run into oriental masterminds, seductive ladies, furtive guys-who-know-too-much and the odd bruiser just looking for a fight.

All this comes off much better than it deserves, thanks mostly to Constantine’s brutal charisma. Projecting a screen persona somewhere between Humphrey Bogart and the Creature from the Black Lagoon, he lumbers gracefully across the screen, and somehow convinces you that yes, he really is that tough.

The story lumbers a bit too, I’m afraid — not so much a story as a succession of fights and chases, but writer Carriere does what he can with it. Some of the repartee is genuinely funny, there are a couple of amusing twists (as when a squad of killer robots and a gang of Chinese assassins prepare to ambush our hero in his room and suddenly discover each other’s presence) and we even get an oriental mastermind with a sense of humor.

Perhaps no film should need so many redeeming features, but this one somehow carries it off, and if you’re in the mood for something mindless, it fills the time very pleasantly.