Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

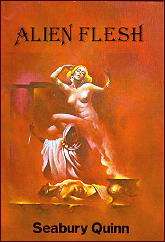

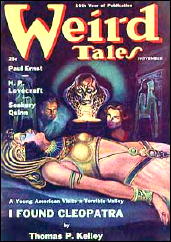

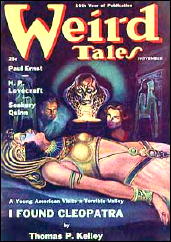

SEABURY QUINN – Alien Flesh. Oswald Train; hardcover, 1977. Introduction by E. Hoffman Price; illustrations by Stephen Fabian. Expanded from the short story “Lynne Foster Is Dead!”, Weird Tales, November 1938.

There is a type of book that can only be called a peculiar classic; not a work of great literature, and yet both memorable and remarkable. Inevitably such books are faintly redolent of the decadent, faintly touched with the strange; Huysman’s La Bas and Against the Grain are such books, so were the works of E. H. Visiak and William Beckford, so Mari Corelli’s The Sorrows of Satan, and James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen. Everything William Morris wrote falls under this umbrella and most of Lord Dunsany.

And so does Seabury Quinn’s Alien Flesh.

Seabury Quinn reigned supreme in the old pulp Weird Tales. The popularity of his tales of psychic sleuth Jules de Grandin and his Watson, Dr. Trowbridge, far surpassed the popularity of H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch or any of the other legendary names associated with the magazine. He even produced one genuine classic, the haunting Christmas story Roads (the legendary Arkham House edition illustrated by science fiction master Virgil Finlay is one of the most attractive books ever printed by a small press)..

Alien Flesh is a novel, written after Weird Tales glory days, in 1950 not long before the series of strokes that ended Quinn’s fiction writing career. He lived until 1969, but no longer churned out tales of vampires, werewolves, cults, and covens, and only one book like Alien Flesh. Not that there could be more than one book like Alien Flesh.

“For sweet God’s sake, who is she, Conover?”

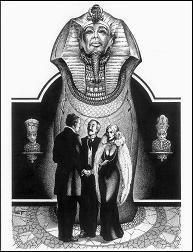

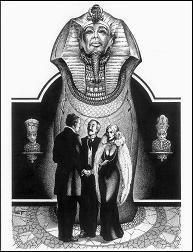

She came slowly toward them passed the rows of glassed-in mummy cases. She was not tall, but very slim, with the force maigruer of youth, and wore a daringly low-cut evening gown of midnight blue and a blonde knee length mink coat draped crosswise across her shoulders. Her eyes were amber and her honey colored hair was drawn back from a pronounced widow’s peak to be looped in a loose figure eight at the nape of her neck … she was like Clytie in a velvet gown, Titania in pearls and mink. If she had suddenly unfolded moth- wings and taken flight Arundel would not have been too much surprised.

Hugh Arundel, Egyptologist, attending a new Egyptian exhibit at a New York museum is introduced to the fabulous Madame Foulik Bey, Ismet.

And something draws Arundel to her, something in her strange manner, and stranger eyes, something he can’t quite put a finger on.

In short order his life revolves around her. She becomes the axis all aspect of his thoughts turn on. And at every turn a new mystery, her nature possessing, “as many facets as a diamond.”

And yet despite her obvious feeling for him she holds him at bay.

Finally he pushes her and she relents and tells him her story,

“Tell me what you know about Lynne Foster, especially what you know about him now,” he heard her saying.

Lynne Foster was a boyhood friend. They had gone to school together, dated together, both been fascinated with Egypt. Lynne Foster had disappeared in Cairo, possibly murdered.

“…Can you supply the ending of the story?”

“Here is the ending!” she knotted her small hands into fists and struck herself on the breast. Her head was thrown back, and her eyes were flushed with tears. “I am — or was — I don’t know which — Lynne Foster.”

And then she relates her — Lynne Foster’s — tale.

I did warn you this was a peculiar classic.

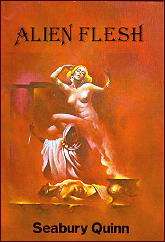

Lynne Foster in Egypt fell afoul of ancient sorcery, and in his western arrogance was punished. He was transformed, from the strong and tough minded young man to …

I rose, walked slowly toward the mirror, and the girl walked towards me with a cadenced, sensuous swaying of slim hips and pointed breasts. Arm’s length from the looking glass I halted and put out my hand. The mirror girl’s slim hand came up to meet mine, but instead of warm flesh I encountered cool hard glass. I turned to look behind me.

Besides me there was no one else in the room!

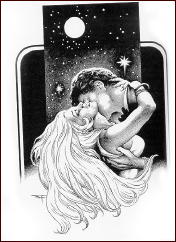

As you might imagine this could go wrong very quickly, and it is a testament to the old pulp master’s skills that it does not. He finds a fine balance between horror, humor, whimsy, unabashed Arabian nights, the erotic — suggested but never spelled out — and sensuality — the book drips with that — as he spins out the tale of the fortunes of Lynne Foster, now Ismet a simple harem girl.

Again, I said this was a peculiar book and it is difficult to convey to any reader how well Quinn handles this difficult theme without slipping into either soft porn or outright comedy. The book recounts Ismet’s adventures, her first touches of romance in her new body, her battle with the mind of Lynne Foster and the emotions of the woman Ismet, and her rise to riches and power using Lynne Foster’s masculine mind and Ismet Foulik’s feminine charms.

I’m not sure I buy the sweepingly romantic ending, but Quinn more than prepares you for it, and after all, Hollywood used to churn out this kind of fantasy with regularity — though usually in the form of Thorne Smith comedy such as Turnabout or I Married A Witch.

Here it is deadly serious, but handled so deftly that the giggles that could easily turn to guffaws and destroy the entire mood are held at bay (at least while you are caught in Quinn’s spell, I can’t answer for later) and the reader manages to stay with Quinn thanks to his sheer story telling skills.

Once he gets you on his side he keeps you there, and plays deftly with both the reader’s willingness to suspend disbelief and also the key to any storyteller’s success, the readers desire to see what happens next. Quinn knew how to spin a tale and keep the pages turning, and here those skills serve him well. This isn’t the sort of book that can survive much in the way of the reader stopping to meditate on the story.

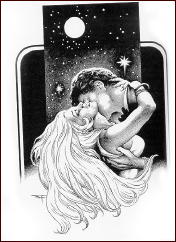

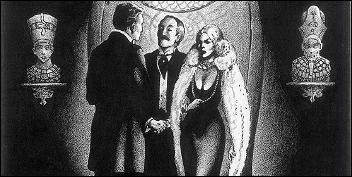

When this was reissued in 1977 by Oswald Train it came with an appreciative forward by Quinn’s friend and former pulp master E. Hoffman Price, a beautiful color cover by illustrator Stephen Fabian, and a full accompaniment of full page black and white illustrations also by Fabian. It’s a lovely little book and a perfect tribute to this most peculiar of peculiar classics.

I know many of you reading this description of the book, are going to say there is no way it could work in the form Quinn gives it, and no doubt it would not for many readers, but Alien Flesh, given half of a chance earns it’s place on that shelf of peculiar classics, and earns Quinn this much from me — I can’t think of another writer who could have pulled it off with half the charm, skill, and old fashioned pulp romanticizing.

If nothing else you turn each page just to see if he avoids the obvious traps — which he always does — and you reach the end glad to give him his choice of endings thankful for the memorable trip.

“… the past has lost all meaning — and all menace.”

And one more peculiar classic finds its way onto the shelves.