Sat 19 Jun 2010

Archived Review: SIMON GREEN – Hawk and Fisher.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Reviews , Science Fiction & Fantasy[4] Comments

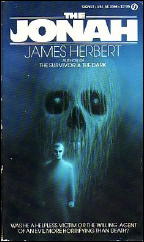

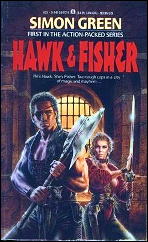

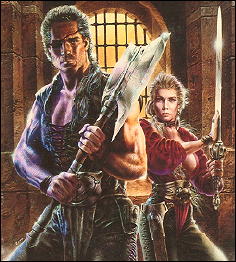

SIMON GREEN – Hawk and Fisher. Ace, paperback original; 1st printing, September 1990. Reprinted in Swords of Haven: The Adventures of Hawk & Fisher, an omnibus edition containing the first three books in the series; see below. Penguin/Roc, July 1999; trade ppbk, June 2006.

It is quite remarkable how you can come across the most interesting sorts of things when you least expect them. No one looking for the best locked room mystery written in 1990 (I wager to say) would ever in their right mind pick this book up to read — looking as it does as the latest variation of the Conan-based fantasy-action series that clog the science fiction shelves in every Waldenbooks store in the country.

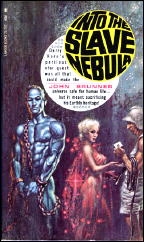

Hawk and Fisher (male and female, and married to each other) are two captains of the guard in the dark city of Haven, on some unknown world at some unknown time, where magic works, and vampires, werewolves and succubi abound. (He has a patch over one eye, and she wears a shirt that exposes an ample amount of bosom, as well illustrated on the front cover.)

They are both tough, and even more remarkably, they are both honest, a rarity in Haven.

After disposing of a particularly bothersome vampire, they are asked to investigate the stabbing of an important reformist councilor in his locked bedroom. The crime could not have been committed by a magical spell, as first suspected, as the dead man wore an amulet about his neck designed especially to ward off such attacks.

Being a reformist in local politics means that the victim had many enemies, but the only ones who could have killed him are trapped in the house with him. Thus what this resembles, in perverse but strangely believable fashion, is an exceptionally good isolated county manor caper, complete with false trails, red herrings, and fine old-fashioned detective work.

The solution to the crime, reasonably intricate, is meticulously worked out as well. I can’t see any flaws in the story, which certainly triggered all the right responses in me. I don’t know how easy it will be for you to get your hands on a copy, but since several more in the series have appeared in the meantime, it’s possible Ace may have kept them all in print. Highly recommended.

And from later on, from the same issue of Mystery*File:

SIMON GREEN – Winner Takes All. Ace, paperback original; 1st printing, January 1991.

The second in Green’s “Hawk & Fisher” series. The first, Hawk & Fisher, was an extremely pleasant surprise — a well-written locked room mystery taking place in a world of pure fantasy.

This new adventure of the two married members of the Guards is pure politics, however, as election time is nearing. Lots of swords, lots of evil sorcery, lots of action. Entertaining, but still a disappointment in not living up to expectations.

The Hawk & Fisher series:

Hawk & Fisher. Ace, September 1990.

Hawk & Fisher: Winner Takes All. Ace, January 1991.

Hawk & Fisher: The God Killer. Ace, June 1991.

Hawk & Fisher: Wolf in the Fold. Ace, September 1991

Hawk & Fisher: Guard Against Dishonor. Ace, December 1991.

Hawk & Fisher: The Bones of Haven. Ace, March 1992.

The six books were reprinted in two omnibus editions. The first is so mentioned above. The second grouping of three titles was entitled Guards of Haven, Penguin/Roc, ppbk, November 1999; trade ppbk, June 2007.

Editorial Comments: The artwork is so finely detailed it does not show up well in normal-sized images; hence the blow-up, as you see!

Also, George Kelley has just reviewed the two omnibus editions of Hawk & Fisher books on his blog. You can read his comments by following this link.