Tue 17 Aug 2010

Review: HERBERT FLOWERDEW – The Villa Mystery.

Posted by Steve under Crime Fiction IV , Pulp Fiction , Reviews[8] Comments

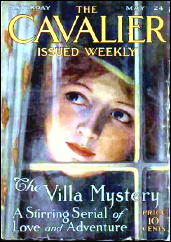

HERBERT FLOWERDEW – The Villa Mystery. Brentano’s, US, hardcover, 1912. First published in the UK: Stanley Paul, 1912. Serialized in The Cavalier, May 24 through June 21 1913. Also available online here and in various POD editions.

Before I discovered this book online and in various Print on Demand editions, I saw the title and author in this blog’s recent checklist of “Serials from Argosy Published As Books†and found a copy of the Brentano’s hardcover edition without too much difficulty. For less than twenty dollars in fact, which is one heck of a lot cheaper than finding a complete set of the five issues of The Cavalier which it appeared in.

Of course, it does me no good to brag about this, not when you can read it online for free.

But should you? Can an obscure mystery or detective novel written in 1912 be worth the time and effort? My answer’s yes, given certain conditions, and I’m about to tell you why.

The story’s definitely an old-fashioned one – how could it not be? – and if you have an allergy to old-fashioned stories, you might as well stop reading this review right now. It begins with a young girl, totally destitute, making her way to a former friend of her dead father, a wealthy man who has refused to repay a loan.

But now that she has found the IOU, which had gone missing, she hopes to persuade him to repay his debt — but he refuses to listen to her, requiring her to return in the morning. He has no time to listen to her now. She leaves, but then returns to watch through the window of the study where she saw him earlier before entering once again, leaving the IOU and making off with a suitcase of money she has decided is rightfully hers.

In making her way back to the train station, however, she is accosted by one man and rescued by another. In the way that the world worked back in 1912, the latter is the stepson of the man whose debt to Elsa Armandy has been repaid in such an unorthodox fashion.

In another of the ways that the world worked back in 1912, Nehemiah Grayle is soon found dead, possibly a suicide (or so the butler claims) but more probably not. Compounding Esmond Hare’s deepening dilemma, for he believes the girl’s story (and she is most attractive) is that to remove her from suspicion means incriminating his own mother, now estranged from the dead man.

There is a local detective in charge of the case, but it is on Hare’s shoulders that solving the crime falls. But this is a story of romance as much as it is one of detective work, with much missing of connections as the characters move here and there and do not stay where they are supposed to stay, mostly because of revelations and stories not quite believed or not told in timely enough fashion.

And all the while staying out of the hands of the police, especially Elsa, but Esmond also, who fears he may say and reveal too much if he is questioned further.

Delicious, I say. They don’t write stories like this very much any more. But what’s even better is that there really are some even more delightful twists and turns in the detective side of things, including a final explanation which is really quite clever, almost as clever as one found in the best of the Golden Age of Detective stories.

It’s just a little awkward in the telling, I have to confess, and there are some even clumsier aspects of the clues and what the characters make of them earlier on, in their naively old-fashioned way, so it’s with these caveats that I do recommend you read this one.

Bio-Bibliographic Notes: There are 16 books listed for the author in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, but nine of them are indicated with a hyphen as being only marginally criminous.

Herbert Flowerdew died in 1917 at the age of only 51. If he’d lived longer, perhaps he’d have taken this book as a stepping stone to a more significant mystery writing career, but that alas, we’ll never know.