Mon 13 Apr 2020

PI Stories I’m Reading: RAYMOND CHANDLER “Wrong Pigeon.â€

Posted by Steve under Stories I'm Reading[4] Comments

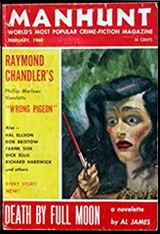

RAYMOND CHANDLER “Wrong Pigeon.†Short story. PI Philip Marlowe. First magazine publication in Manhunt, February 1960. Previouslypublished, possibly in abridged form, in a British newspaper as “Marlowe Takes on the Syndicate.†Later reprinted as “Philip Marlowe’s Last Case†in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (January 1962) and as “The Pencil” in Argosy (September 1965). Collected as “The Pencil†in The Smell of Fear (H. Hamilton, UK, 1965). Reprinted in Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe: A Centennial Celebration, edited by Byron Preiss (Knopf, 1988) and as “Wrong Pigeon†in The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carroll & Graf, 1988), among others. TV adaptation: As “The Pencil†on Philip Marlowe, Private Eye, 16 April 1983 (season 1, episode 1), starring Powers Boothe.

And with all of that, I’ve still probably missing something obvious. It was, as the title of the story as it appeared in EQMM, PI Philip Marlowe’s last case, Raymond Chandler having died in 1959, and it’s a good one. Marlowe takes on a job for a guy who wants to get out of the mob, but there’s been a pencil drawn through his name, and he knows the syndicate does not take defections lightly.

It’s a fool’s task, but the promise of $5000 upon completion of a successful escape has a loud way of talking, and that’s in 1959 money. And Marlowe is no fool. He knows that there’s a reason why the job is done so easily. He’s right, of course, and you should be. too, the reader.

It’s been a long time for me to get around to reading this one, and I’m glad I did. I don’t know what the general opinion is of this story, but I think Chandler was still in fine form when he wrote it. The story is light and breezily told, but when it comes down to it, Marlowe is as hardboiled as private eyes really ought to be, especially when it comes to dealing with the syndicate. Very enjoyable.