Sun 24 Apr 2022

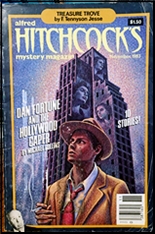

PI Stories I’m Reading: MICHAEL COLLINS “Dan Fortune and the Hollywood Caper.â€

Posted by Steve under Stories I'm Reading[2] Comments

MICHAEL COLLINS “Dan Fortune and the Hollywood Caper.†PI Dan Fortune. Short story. First published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, November 1983. Collected in Crime, Punishment and Resurrection (Donald I. Fine, 1992) as “The Woman Who Ruined John Ireland.†Reprinted in Silver Screams: Murder Goes Hollywood, edited by Cynthia Manson & Adam Stern (Longmeadow, paperback, 1994).

Dan Fortune is hired by a young woman, a file clerk for a company in midtown Manhattan, who lives a life on the borderline between real life and movieland fantasy. She looks like Gloria Grahame, and there are times when she thinks she is. She is having an affair with the manager of a small used bookstore whom at times she believes he is John Ireland. When she is shot at, she comes to Dan, convinced that her lover’s wife, Grace Kelly, is the one responsible.

Before he has solved the case, she even has Dan doing it. Here below is a list of the movie stars who play a part in the investigation, even briefly. I hope I haven’t missed any. It would make one hell of of a movie, wouldn’t it?

John Ireland

Grace Kelly

Alan Ladd

Elliott Gould

Ingrid Bergman

Bonita Granville

Dick Powell

Robert Mitchum

Robert Ryan

Burt Lancaster

Jack Nicholson

Robert Montgomery

Dan Duryea