Wed 10 Aug 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS Part 5.2: Theatre of Crime (UK).

Posted by Steve under Columns , TV mysteries[8] Comments

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 5.2: Theatre of Crime (UK)

British television in the 1950s and 1960s seemed to be choking itself on claustrophobic, heavily-theatrical studio-based plays (often live, sometimes taped). The BBC seemed shackled to the home theatre approach while newcomer ITV (from late 1955) tended to favor young TV writers (the provocative Armchair Theatre, ITV, 1956-74, for example) alongside somewhat wild and adventurous themes (the early Honor Blackman period of The Avengers, ITV, 1961-69).

Themes or strands, usually explained by the title, such as The Villains (ITV, 1964-65), Blackmail (ITV, 1965-66) and Seven Deadly Sins (ITV, 1966) or by a general heading like Suspense (both ITV, 1960; and BBC, 1962-63) were very much in style during the 1960s, but I have disregarded many of these because they represent nothing more than simple crime-and-comeuppance yarns. It is sad to consider that over a decade later such predictable collections as the 1978 ITV series Scorpion Tales didn’t improve the British TV genre very much.

The mid-1960s even saw a brief fascination with the fogbound period of Gaslight Theatre (BBC, 1965) and Mystery and Imagination (ITV, 1966; 1968; 1970). At the same time reveling in the Victorian-era police procedurals of Sergeant Cork (ITV, 1963-64; 1966-68) or penetrating the pea-soupers of Sherlock Holmes (BBC, 1965).

Here I have focused on the more obvious or more interesting genre anthologies shown on UK television during the past half century. (Some of them may even be found on DVD via Amazon-UK or NetworkDVD.)

One of the earliest was Tales from Soho (BBC, 1956), Berkeley Mather’s less-than-serious take on the notorious central London area. A curious point of interest to emerge from this lightweight collection, however, was one Chief Detective Inspector Charlesworth (played by John Welsh) who went on to his own series. Now featuring Wensley Pithey as Scotland Yard Detective Superintendent Charlesworth, the series was called Big Guns (BBC, 1958). Mather followed up with Charlesworth at Large (BBC, 1958) and Charlesworth (BBC, 1959).

Something of an unexpected pleasure, Hour of Mystery (ITV, 1957) was hosted by the fearsome Donald Wolfit. Among the episodes were “The Man in Half Moon Street” (with Anton Diffring), “The Woman in White”, Emlyn Williams’ “Night Must Fall” and “A Murder Has Been Arranged”, and Ivan Goff & Ben Roberts’s “Portrait in Black” (filmed in 1960 by Universal).

Armchair Mystery Theatre (ITV, 1960; 1964-65) was the summertime replacement for the long-running Armchair Theatre and featured stories by Michael Gilbert (“The Blackmailing of Mr. S.”, 1964), Julian Symons (“The Finishing Touch”, 1965) and Mary Belloc Lowndes (“The Lodger” (1965).

British-made (at MGM British Studios) for producer Herbert Brodkin’s Plautus Productions (US), the filmed anthology Espionage (NBC/US and ITV/UK, 1963-64) was one of the more intelligent contributions to the then-raging 1960s spy cycle. The Larry Cohen-scripted “Medal for a Turned Coat” (starring Fritz Weaver) remains a particular favorite with this writer.

BBC’s mid-1960s anthology Detective (BBC, 1964; 1968-69) has in the eyes of fans achieved almost legendary status, perhaps due in great part to this 45-episode series being “missing believed wiped.” For now, I’ll list just a few episodes that gave rise to some fascinating series:

The episode “The Drawing” (1964), scripted by Gil North [Geoffrey Horne], featured North-country Detective Sergeant Cluff (played by Leslie Sands) and soon became the rather leisurely but enjoyable Cluff (BBC, 1964-65). The episode “The Speckled Band” (1964), needless to say, went on to become Sherlock Holmes (BBC, 1965) with Douglas Wilmer as Holmes and Nigel Stock as Watson; Peter Cushing took over as Holmes for a 1968 revival of the series. A third episode to spin-off from the anthology was “The Case of Oscar Brodski” (1964), from the works by R. Austin Freeman, and became the series Thorndyke (BBC, 1964) with Peter Copley as the methodical Doctor Thorndyke; this series, too, appears to be “missing believed wiped.”

Even while the legendary anthology Detective was enchanting grateful viewers, BBC’s Story Parade (1964-65) was lurking in the background with Ira Levin’s “A Kiss Before Dying” (1964) and, more importantly, Isaac Asimov’s “The Caves of Steel” (1964). This latter story featured the fascinating detective partnership of Elijah Baley (Peter Cushing) and the robot R. Daneel Olivaw (John Carson); depressingly, the original episode is said to no longer exist.

Outside of the 1960-63 Maigret series, BBC’s other celebration of Georges Simenon was captured in the non-Maigret collection Thirteen Against Fate (BBC, 1966). The collection was a stately-paced human condition drama, focusing on an individual in an unusual predicament; mercifully, the majority of these episodes have recently been rediscovered.

Leaning more on the horror and supernatural element, ITV’s very atmospheric Mystery and Imagination during the mid-1960s also found time to feature, among other dark mystery tales, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1966), Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Body Snatcher” (1966) and “The Suicide Club” (1970), and Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Uncle Silas” (1968).

Non-Sherlock Holmes stories made up Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (aka The Short Stories of Conan Doyle; BBC, 1967), a 13-part collection of stories ranging from the horror-fantasy of “Lot 249” to “The Mystery of Cader Ifan”. For the most part, the stories were dramatized by TV writer John Hawkesworth, who went on to immortalize Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock Holmes in the 1980s.

The series called Armchair Thriller (ITV, 1967) lasted a relatively short time but in its slight existence did manage to present Jack Trevor Story’s “In the Name of the Law” among its mere five outings. However, a more notable series under the same title (ITV, 1978; 1980) presented the six-part “A Dog’s Ransom” (1978) from the book by Patricia Highsmith, and the six-part “Quiet as a Nun” (1978) based on a book by Antonia Fraser (the first of a series of books that was spun-off as the 1983 series Jemima Shore Investigates for ITV). A six-part serial of Lionel Davidson’s “The Chelsea Murders” was also produced but not shown on UK TV until an edited version (condensed to 104 minutes) was broadcast in 1981. The Davidson novel was published in the U.S. in 1978 as Murder Games.

Starting off as a small series of plays under the ITV Playhouse: Rogues’ Gallery banner in 1968, including the wonderfully bawdy “The Lives and Crimes of Jonathan Wild and Jack Sheppard,” a six-part series called simply Rogues’ Gallery evolved in 1969 (ITV), featuring doom-laden tales of highwaymen and Newgate Prison.

Being recorded on icy-cold videotape didn’t somehow diminish the fascination of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (ITV, 1971; 1973). Among the compelling dramas were William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki in “The Horse of the Invisible” (1971), Baroness Orczy’s Lady Molly of Scotland Yard in “The Woman in the Big Hat” (1971) and Jacques Futrelle’s Van Dusen in “Cell 13” (1973). This series represented one of the most interesting and enjoyable collections to appear on UK television.

Alternating between the woman-in-jeopardy story and the supernatural-fantasy, Brian Clemens’ Thriller (ITV, 1973-76) was a passable series of 65- and 75-minute mini-movies (albeit videotaped). Moments of enjoyment could be had in edge-of-the-seat dramas such as the would-be pilots “K is for Killing” (US: “Color Him Dead”; 1974), with Gayle Hunnicutt and Stephen Rea as a couple of amateur sleuths, and “An Echo of Theresa” (US: “Anatomy of Terror”; 1973) and “The Next Scream You Hear” (US: “Not Guilty”; 1974), the latter two with Dinsdale Landen as the likeable but overly confident private investigator Matthew Earp.

Anglia Television in association with 20th Century Fox Television produced Orson Welles’ Great Mysteries (ITV, 1974-75), with the slouch-hat-and-caped one hosting some intriguing presentations of Conan Doyle’s “The Leather Funnel” (1974), Wilkie Collins’s “A Terribly Strange Bed” (1974), and Dorothy L. Sayers’ “The Inspiration of Mr. Budd” (1975). The series was curiously reminiscent of Hammer Films’ teaming with 20th Century Fox in 1968 for the collection Journey to the Unknown which, in the latter instance, was resolutely geared to scare the living daylights out of the viewer.

The 13-part thriller anthology with stories connected by the theme of the telephone, Dial M for Murder (BBC/Warner Bros, 1974), was invested with more imagination (by producer Jordan Lawrence) than most contemporary thriller series. While some presentations were indeed tedious, most of the stories were simply dripping with suspense. One of them, Julian Symons’s “Whatever’s Peter Playing At?,” attracted the attention as being just a notch above the average.

Somehow you knew that when Tales of the Unexpected (ITV, 1979-86; 1988) was shown as Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected during its early years it was inevitable that “Man from the South,” “Mrs. Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat” and “Lamb to the Slaughter” would be included.

Thankfully, the series also drew on stories by Stanley Ellin, Bill Pronzini, John Collier, Henry Slesar, Ruth Rendell, Helen Nielsen, Peter Lovesey and Patricia McGerr among many others. Even so, the general feeling was that it had all been done much better before in Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Some of the stories in The Agatha Christie Hour (ITV, 1982) were just plain silly and embarrassingly dated but most, when taken on their own level, were unexpectedly rewarding. The stories featuring the delightful Maurice Denham as Parker Pyne who runs a sort of dream-fulfilment agency are among some of the best. One of these Pyne stories was “The Case of the Discontented Soldier,” about William Gaunt’s retired-but-restless military major who is given his own Bulldog Drummond adventure; Lally Bowers also appeared in this story as Mrs. Ariadne Oliver.

Based on the works by the title author, The Ruth Rendell Mysteries (ITV, 1987-2000) consisted of some of the author’s crime thriller tales as well as her Detective Inspector Wexford stories (the latter series starring George Baker). Among the non-Wexford episodes the series presented the three-part “Vanity Dies Hard” (1995), in which a lonely woman investigates the disappearance of her friend, the two-part “The Secret House of Death” (1996), where a woman becomes involved in the sudden death of the neighboring couple, and “Thornapple” (1997), featuring a young boy embroiled in poisonings and inheritance.

Rating as something of a disappointment was the nevertheless interesting-sounding Frederick Forsythe Presents (ITV, 1989-90), a short-run espionage drama based on stories by the title author. While all the components seemed in order with some fine directors (Tom Clegg, Lawrence Gordon Clark, Ian Sharp) and top-notch players (Beau Bridges, Brian Dennehy, Lauren Bacall, Tony Lo Bianco) the anthology suffered from the “too many chefs” syndrome of having too many producers and co-production companies.

A similar fate befell another interesting collection, Mistress of Suspense (ITV, 1990; 1992), based on six (hour-long) stories by Patricia Highsmith. Something to enjoy and savor became instead a jumbled concoction due to its myriad producers and co-production companies.

Murder in Mind (BBC, 2001-2003) was a diverting anthology of psychological crime dramas written by the brilliant Anthony Horowitz. The series turned out to be one of the true delights of genre TV. Horowitz composed such spellbinding stories as “Motive,” where a married couple believe they have committed the perfect murder; “Flashback,” in which a barrister “defends” the man he has framed for murder; and “Echoes,” where a woman investigates the past when a centuries-old body is found in her garden. Told from the detailed perspective of the hunted (the criminal) rather than the hunter (police), Murder in Mind may very well have been one of the high points of British television crime drama.

Although I’m sure there are many interesting anthologies that I’ve overlooked or have simply forgotten, the previous Parts and the above should be regarded simply as a general overview.

The next Crime & Mystery Part intends to survey The Black Mask Style, the late 1950s private eye phase of 77 Sunset Strip, Richard Diamond, Mike Hammer and Peter Gunn.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

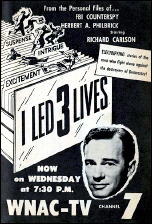

Part 5.0: Theatre of Crime (US).

Part 5.1: Theatre of Crime (Hours of Suspense Revisited).