Mon 12 Feb 2024

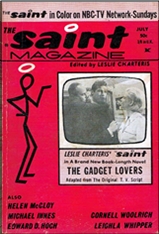

Diary Review: THE SAINT MAGAZINE July 1967.

Posted by Steve under Diary Reviews , Magazines[4] Comments

THE SAINT MAGAZINE. July 1967. Editor: Hans Stefan Santesson. Overall rating: ***

FLEMING LEE “The Gadget Lovers.” Simon Templar. Complete novel (73 pages), adapted from a teleplay by John Kruse. Russian spies are being murdered by exploding equipment, and naturally enough the Western allies are suspected. The Saint is sent to stop the assassination of a Colonel Smolenko, who turns out to be a woman. It is her idea to play the part of his secretary, as he becomes the target. The trail leads to Switzerland and to a monastery taken over by the Chinese. The handicaps of TV restrictions, and the required flashy beginning, are very well overcome. If the idea of a beautiful woman as a Russian officer can be accepted, the story becomes an interesting study of East meeting West. ****

MICHAEL INNES “Imperious Caesar.” John Appleby. First appeared in MacKill’s Mystery Magazine, April 1953. A malevolent professor commits suicide during a bloody Shakespearean production (4)

HELEN McCLOY “Through a Glass, Darkly.” Novelette. First appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, September 1948. Basil Wiling takes on the case of a woman who fears meeting her supernatural double. She has reason, for it is part of a plot to frighten her to death. Too many people take it too seriously, (2)

LEIGHLA WHIPPER “Death Comes of Chuchu Valente.” Miss Bennett [a recurring character], professional assassin, is hired to kill a Mexican bullfight announcer. Ridiculous. (1)

EDWARD D. HOCH “The Oblong Room.” Captain Leopold. An LSD religious experience leads to murder in a dormitory room. (3)

CORNELL WOOLRICH “Screen Test.” Jimmy Galbraith. First appeared in Dime Detective, November 1934, as “Preview of Death.”. A request for police protection fails as the heroine’s dress goes up in flames on the [movie] set, but the detective solves the case by watching the film rushes. A good story. (3)