March 2007

Monthly Archive

Mon 26 Mar 2007

FLY AWAY GIRL. Warner Brothers, 1937. Glenda Farrell, Barton MacLane, Gordon Oliver, Hugh O’Connell, Tom Kennedy.

It must have been Glenda Farrell Day sometime last year at Turner Classic Movies, or at a minimum, Torchy Blane Day, since I’ve just discovered that I taped a complete sequence of the Torchy films that day, all eight of them. I watched a few of them last year, decided I didn’t want to overdose on them, put them aside – and promptly forgot about them until a couple of days ago when I came across them again.

This one’s number two in the series, in case you’re counting. I can’t exactly tell you what the appeal is with these movies, since the mystery plots are kind of sappy and so are the characters, to tell you the truth. It’s been a while since I watched the first one, Smart Blonde (1937), so I’d rather you didn’t quote me on this, but I have the feeling that the detective element was the strongest in that one, before the comedy became more and more significant. Since it’s also the only one that was based on a Frederick Nebel pulp fiction story, I think I’m safe enough in saying so.

Torchy Blane is an ace newspaper reporter, and she must have been quite a model for plenty of young girls in the late 30s and early 40s, because she is an ace, female or not. Her boy friend (or fiancé, more or less) is Lt. Steve McBride (Barton MacLane), who has an ordinary mind for police work and who (therefore) is no match for Torchy. You might consider him lunk-headed, but I think that is why Tom Kennedy is in these movies, as Sgt. Orville Gahagan, a poor poetry-spouting sap who lives for nothing more to use the siren whenever he’s whisking McBride off to the next scene of the crime. Gahagan makes McBride look positively Holmesian in comparison.

The plot in this particular episode in their lives centers around the murder of diamond merchant in his office, but Torchy’s choice for the killer, a reporter with a rich father, seems to have an iron-clad alibi. When her candidate for a killer takes an around-the-world tour as a newspaper stunt, Torchy talks her editor into allowing her to tag along, hence the title.

Actually, I do know what the appeal is for these movies. It’s Torchy herself, or rather Glenda Farrell who plays her: fast-talking and fast-thinking, brassy without being bold, funny and wisecracking, but her mind on only one thing, her story. The photo of her that you see above didn’t come from this movie. I couldn’t find any, I’m sorry to say, but I thought this publicity still would do fairly well in its place.

Sun 25 Mar 2007

After Vince Keenan and I finished our email conversation on Mike Shayne and the actors who have played him over the years, I didn’t think it was going to take long for Vince to go through all four films on the first DVD set, once I knew they were in his hands, and I was right. Even though not especially looking the part, Lloyd Nolan was very impressive in the role, he says, making me all the more anxious for my copies to get here in the mail.

I’ll have to send you over to his blog, though, but it’s only a click away and it’s well worth the trip.

Vince also sent me an email about the Mike Shayne radio show I set up a link to. His response: “I listened to the Shayne radio show and enjoyed it quite a bit. Jeff Chandler may look nothing like that portrait of Shayne, but he’s got the attitude down pat. And that ending — what a corker!”

Given that kind of reaction, I figured I ought to do something about it. If you go this OTR Archives page, you will find links to around 30 or 35 of them. Just click and play, or download and burn to CDs if you wish. I haven’t listened to the sound quality of all of these, but the higher the Kbps, the better, I think — try those in the column furthest to the right first. Jeff Chandler’s the star in all but the first one (from 1946) and the last (from 1953).

Sun 25 Mar 2007

A few months ago I was asked if I had any information on writer Mary McMullen, who wrote nineteen mysteries between 1952 and 1986, when she passed away. Most of these books were published by Doubleday’s Crime Club imprint and can be generally classified as being in the “malice domestic” genre. Without a series character to maintain readers’ interest in her stories, she’s on the verge of being forgotten, but no one writes that many works of crime fiction without having had a substantial following at the time.

What’s the most interesting about Mary McMullen, perhaps, is her family. When I did a bibliography for mystery writer Helen Reilly following Michael Grost’s excellent analysis of her crime fiction, I said:

Helen Reilly [nee Kieran]. Married to artist Paul Reilly, mother of four daughters, including mystery writers Ursula Curtiss and Mary McMullen. Her brother, James Kieran, also wrote mystery fiction.

Helen Reilly’s primary character was Inspector Christopher McKee. In Mike’s essay on her, he considers the McKee books as very early police procedurals, but he also connects her work up with the Black Mask style of writing, in the hardboiled pulp tradition.

My impression of Ursula Curtiss’s books is that they are much like her sister Mary McMullen’s, but stronger on the suspense. If you’ve read any of them recently, though, and can tell me otherwise, I’d surely like to be corrected. Ursula Curtiss is listed in CFIV as the author of 22 novels and one collection of short stories, the books appearing at regular intervals between 1948 and 1985.

Besides James Kieran, the brother mentioned above, there was another well-known member of the family, John F. Kieran, the sportswriter who was a long-time panelist on radio’s Information Please in the 1940s, among other accomplishments.

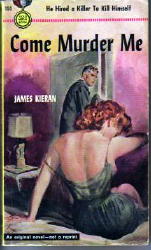

James Kieran’s impact on the world of mystery fiction is small, but the reason will soon become clear. He has only one entry in CFIV, as follows, in slightly expanded form:

KIERAN, JAMES (1911-1986)

* * Come Murder Me. Gold Medal #150, 1951, pbo. Reprint: Gold Medal #419, 1954.

About this time, Victor Berch, whom I’d asked for assistance on the original inquiry about Mary McMullen, sent me the following email:

I was following the discussion about Mary McMullen, and when the subject of James Kieran came up, I decided to look into him. Don’t ask why. Maybe, it’s because he’s a Gold Medal author and I have the two printings of

Come Murder Me (GM 150 and 419).

[In Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV] James Kieran’s dates [are given] as 1911-1986. I think this is the wrong James Kieran. Out of curiosity (more likely habit), I decided to check with the Copyright Office. Come Murder Me was first registered March 7, 1951. The copyright was renewed Feb. 15, 1971 by Mrs James Kieran. his wife. Then the thought crossed my mind “Why should his wife had to renew the copyright if he was still alive?

Anyhow, the record also gave her full name as Dagmar N. Kieran along with the Mrs. James Kieran appelation. So, I ran a check on her. She was born May 10, 1908 and died Sep. 22, 1985 according to [Social Security records].

However, there is another data base that I sometimes check. It lists people coming in to the USA from foreign ports, both citizens and aliens. The data taken from passports usually give the name of the person, the birth date, place of birth and present address.

And so I found Dagmar N. Kieran and her husband James M. Kieran returning from a trip to Curacao Dec. 7, 1936. James M. Kieran’s birth date was given as September 23, 1901, born in NYC. A check through the NY Times led me to an extensive obituary, which I’ll send along [soon]. He died January 12, 1952. So, his dates and full name should be Kieran, James Michael, Jr., 1901-1952.

He died, that is to say, only year after his only mystery novel was published. As for his family, a brief article in Timemagazine also mentions the Kierans (December 25, 1939):

The Kierans are an active family. John writes sports for the

New York Times, and knows all once a week on radio’s

Information Please; Leo writes aviation for the

Times; Larry works in the Manhattan Surrogate’s office; Helen Kieran Reilly writes detective stories. And there is James M. Kieran, moody, outspoken, firm in his leftish ways, who until last week was Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s press secretary at $5,400 per year.

Last week hot-tempered Mayor LaGuardia announced that he had fired hot-tempered Jim Kieran. “He called me a guinea ———–,” said the Little Flower. “What else could I do?” City Hall ferrets had their own idea of what the row was about: Franklin Roosevelt’s devoted friend Jim Kieran was outraged “because the Mayor lately has buttered up Herbert Hoover.”

Impulsive Mr. LaGuardia quickly regretted his anger, tried to get word to Jim Kieran that all was forgiven. The other Kierans said they had no idea where Jim was. Friends thought they knew. When the Kierans let their Irish get the better of them, they generally retire to Helen’s Connecticut farm to cool off.

Some excerpts from the NY Times obituary for James Kieran will follow, one of them toward the end very interesting, especially if true. It does not seem as though the statement would be in the obituary, if it were not. Of course the degree of involvement is not specified, and it may have been minimal. But here, read for yourself:

Mr. Kieran spent almost all of his newspaper career as a member of the staff of the

New York Times. He came to work in 1923, was a member of the night re-write staff, and then was switched to the political staff. […] He resigned from the

Times in the winter of 1937 to be press secretary to the late Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia.

[After his leaving La Guardia] he entered the public-relations business for a period. […] More recently he collaborated with a sister Helen Reilly, one of the country’s well-known mystery story writers, in a number of books, and also was an author in his own right.

If anyone knows more, we’d love to know about it.

Sun 25 Mar 2007

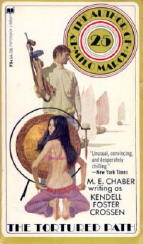

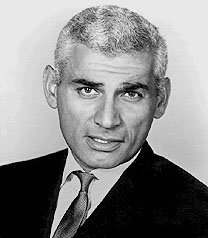

KENDALL FOSTER CROSSEN – The Tortured Path

Permabook M4099; paperback reprint, June 1958. Hardcover edition: E. P. Dutton, June 1957. One chapter appeared earlier in Stag Magazine under the title “The Treatment.” Later paperback edition: Paperback Library 64-706, 1971, as by “M. E. Chaber writing as Kendall Foster Crossen.”

That last byline is rather strange, if you think about it. Kendall Foster Crossen was the author’s real name, and M. E. Chaber was the name he used to write his “Milo March” novels. Paperback Library had been publishing these in uniform editions, all with hugely attractive covers by Robert McGinnis. They must have done well with them, because they when they ran out of Milo March’s adventures to print, to capitalize on Chaber’s popularity, they started doing some of Crossen’s other work in the same numbered format, including this one and several he wrote as by Christopher Monig.

Milo March was basically an insurance investigator, but he also had connections with the CIA, and his adventures took him all over the world. [For more on March, check out his page on the Thrilling Detective website.]

Major Kim Locke, the primary protagonist in The Tortured Path, had even more direct connections with the CIA, and I’ll go into the details in a minute. First, though, here’s a list of the books he appeared in, taken from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

LOCKE, MAJOR KIM

* Kendell Foster Crossen:

o The Tortured Path (n.) Dutton 1957 [China]

o The Big Dive (n.) Dutton 1959 [England]

* Clay Richards:

o The Gentle Assassin (n.) Bobbs-Merrill 1964 [Cuba]

Why the switch in bylines, I don’t know, but it may have had something to do with the switch in publishers. The Big Dive is scarce; it was never reprinted in paperback, and at the moment, there are only two copies of the hardcover edition offered for sale on the Internet. While The Gentle Assassin never had a paperback edition either, it is fairly common in hardcover. It’s also easily available in a three-in-one Detective Book Club edition.

Here are the first couple of paragraphs from The Tortured Path, which will give you more information about Major Locke’s background. It will also supply you with a glimpse of the author’s writing style, or so it’s my intention:

“It started out like any other day in Washington. I’d been cooling my heels there for three months. I was theoretically on duty but I hadn’t anything to do for that length of time. The first month was fine, but then I began to get a little tired of it. I didn’t have an assignment, but I was supposed to check in three times a day. After three months, just checking in was beginning to interfere with my drinking. One thing you can say about Washington – the hunting in the cocktail bars was fine.

“The name is Kim Locke. Major, U. S. Army, permanently attached to the Central Intelligence Agency. Cloak and dagger stuff. But the only cloak I’d ever seen was worn by a blond adagio dancer and the only time I’d been near a dagger was when I was in the OSS during World War Two. There’d been a Yugoslavian partisan who had a dagger; we’d used it to slice the chickens we caught at night and roasted in coals. So it wasn’t like in the books; no willing broads willing to do anything to get your secrets. But it was a living – if you can call being in the Army living.”

His assignment? To get himself caught by the Chinese Communists, be brainwashed and undergo any other form of torture they might devise for him, and then rescue an American officer who has secrets that mustn’t fall into enemy hands.

Which he does. End of book. Well, not quite, but almost. Getting in is far too easy, getting out is another matter, sort of the scorched-earth approach, if you ask me, crude but effective. Crossen has a quiet, breezy style of story-telling, beginning (as you will have seen) with page one onward. The resulting adventure is readable in about a night or two. It is also largely forgettable in about the same length of time.

Sat 24 Mar 2007

ON THE ISLE OF SAMOA. Columbia, 1950. Jon Hall, Susan Cabot, Raymond Greenleaf, Al Kikume. Directed by William A. Berke.

Jon Hall made a career out of making movies (and television shows) taking place in jungles, deserts, and South Seas islands, and obviously this is one of them. Checking out his biography on IMDB, among other items of interest I learned that he was of Swiss/Tahitian descent, and that his mother was a Tahitian princess, and I believe that explains a lot.

And which makes a movie like this one right up his alley, except that as a B-movie it rated a sub-B budget and (as the old saying goes) it probably escaped rather than being released. Hall is also a villain, which is hard to take, given that I remember him most as the star (and hero) of Ramar of the Jungle on TV, episodes of which I believe are available on DVD. I’ve hesitated in picking them up, however, as I’ve been disappointed before in watching what was wonderful when I was ten or twelve and might not be quite so wonderful today.

As badly-tempered Kenneth Crandall in this short film, barely over 60 minutes long, he flees the successful burglary of a nightclub in Australia in a stolen plane, only to crash on an uncharted island during a hurricane (which was more likely a typhoon, if anyone had taken the time to check). The island is inhabited by beautiful women, strong men and one aged missionary (Raymond Greenleaf), who does his best to convince Crandall to renounce his evil ways. But even with the beautifully vacuous Moana (Susan Clarke) as a love interest, Crandall stays remarkably thuggish and unpersuaded.

The only suspense in this film is how long he will resist. To avoid giving away the ending, let me suggest to you that he may never see the error of his ways, and he dies before his heart (and mind) ever softens at all.

Sat 24 Mar 2007

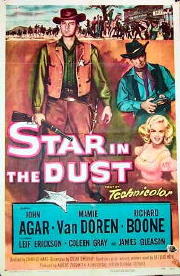

STAR IN THE DUST. Universal, 1956. John Agar, Mamie Van Doren, Richard Boone, Leif Erickson, Colleen Gray, James Gleason, Terry Gilkyson, Harry Morgan. Based on the novel Law Man (Ballantine #51, 1953) by Lee Leighton (Wayne Overholser). Directed by Charles F. Haas.

A “B” western, perhaps, but it packs a lot of drama into its 80 minutes. Folksinger Terry Gilkyson, soloing on his guitar, frames the story from time to time, the tale of a bad man named Sam Hall (Richard Boone), who is to be hanged at sundown at the end of the single day in which the this film takes place.

But why is a review of a western movie here in the first place, on a website dedicated to crime and mystery fiction, you may ask. And I reply, in almost every western, whether in print or on film, there is a crime, and as a bonus, there is often a crime to be solved.

The mystery in this case is, who hired Sam Hall to kill three farmers who (the ranchers say) crossed over the creek into their lands? The sheriff (John Agar), who’s been staying neutral and keeping the peace, has his own battles to fight, trying to live up to his father’s reputation on the job, for one, and salvaging his wedding to the sister (Mamie Van Doren) of the banker (Leif Erikson) who’s the head of the cattleman’s association (see below).

And (as fate would have it) this would-be brother-in-law is his leading suspect as well. It’s a tough job, but Sheriff Jorden seems up to it. You might think that Mamie Van Doren would be out of place in a western drama, but I certainly didn’t mind. It also seems to me that throughout his career James Gleason always played skinny old men, and at the age of 74, when he made this one, he’d finally grown into the part. Richard Boone may have made a better western villain than he did a western hero (Paladin), and even if you may not agree, he’s at his best (that is to say, his nastiest) in this one.

There are a few twists and turns in the tale, more than I expected, but as far as the identity of the man who hired the killer is concerned, unfortunately there is no twist at all. There’s plenty of full color action, though, for those who look for that in their westerns, including one sprawling fight between two ladies who are no ladies at the time at all, neither of whom is played by Mamie Van Doren, who is always very definitely a lady.

Fri 23 Mar 2007

The entry for Gertrude Walker in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, looks like this, or at least this is how it looked until this past week, supplemented slightly by the information on the paperback editions:

WALKER, GERTRUDE (1920- )

* * So Deadly Fair (Putnam, 1948, hc) [Minnesota]. Bestseller B105, digest pb, abridged, 1948. Popular Library 424, pb, 1952.

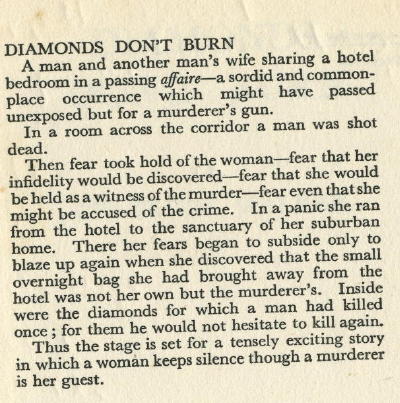

* * Diamonds Don’t Burn (Jenkins, 1955, hc)

* * The Suspect (Major, 1978, pb) [Los Angeles, CA]

So Deadly Fair has a modest reputation among fans of hardboiled mysteries, but otherwise is probably little known. I don’t remember seeing a copy myself, in any of its various editions, although it’s not uncommon, at least in paperback form, so I probably have.

From the blurb on the hardcover edition: “When the Minneapolis-bound freight train pulled out of the small Middletown, Minnesota, freight yard, it left behind it very little of importance: a few rolls of barbed wire, some packing cases, and me. And god knows I wasn’t important. I wasn’t important to anyone. Not even to myself.”

An investigation into both the book and the author began with an email from British bookseller Jamie Sturgeon to Al Hubin:

Al,

Whilst looking for info on Gertrude Walker I found the following on her on IMDB:

It says she married Charles Winninger who she met in 1932 when both were in Showboat. The year of birth you have in CFIV as 1920 seems unlikely to say the least.

I found some more on Gertrude Walker here. This message in [theYahoo group] Rara-Avis mentions a third book The Face of Evil, but I can’t find anything about this title.

Maybe the third book you have of hers listed as The Suspect is by a different Gertrude Walker?

Odd that her second book Diamonds Don’t Burn (the one I have) wasn’t published in the US.

Al sent the email on to me, along with his reply, and I’ll get back to that in a minute.

Taking a look at Walker’s credits in the film-making industry, the following caught my eyes, all more or less in the crime fiction genre:

Mystery Broadcast, 1943. “A radio detective (Ruth Terry) sets out to solve an old murder case, with the help of her sound man and another radio detective.” [Additional dialogue.]

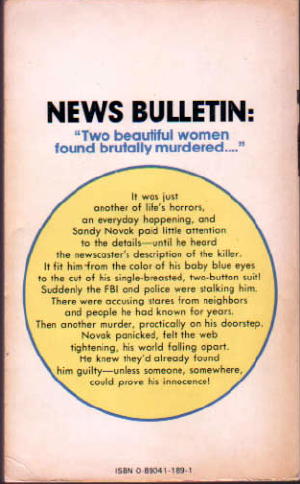

Whispering Footsteps, 1943. “A bank clerk in a small town returns home from a vacation in Indianapolis, and hears a story on the radio about a girl found murdered there. The description of the killer fits him exactly, and when two girls are murdered in his town, suspicion falls on him…” [Co-screenwriter.]

Silent Partner, 1944. “Reporters investigating the death of a friend begin to suspect that their newspaper’s editor may have been responsible for it.” [Screenwriter.]

End of the Road, 1944. “A crime writer believes that a man imprisoned for committing the notorious ‘Flower Shop Murder’ is innocent of the crime…” [Co-screenwriter.]

Crime of the Century, 1946. “Ex-convict Hank Rogers is searching for his brother Jim, a newspaperman, and becomes involved with a group of people trying to conceal the death of the president of a large corporation…” [Screenwriter.]

Railroaded!, 1947. “Sexy beautician Clara Calhoun, who has a bookie operation in her back room, connives with her boyfriend, mob collector Duke Martin (John Ireland), to stage a robbery of the day’s take.” [Original story.]

The Damned Don’t Cry, 1950. “The murder of gangster Nick Prenta touches off an investigation of mysterious socialite Lorna Hansen Forbes (Joan Crawford), who seems to have no past, and has now disappeared…” [Based on Gertrude Walker’s story, “Case History.”]

Insurance Investigator, 1951. “When a businessman who has had a double indemnity policy taken out on him dies mysteriously, his insurance company sends an undercover investigator to town to determine exactly what happened.” [Screenwriter and co-author.]

Some of these I’m sure you may have heard of, others most probably not, but they all seem to fit the category of black-and-white film noir, some more than others, of course. Walker also has a few miscellaneous credits in television, including a stint on The New Adventures of Charlie Chan (1958).

The IMDB link that Jamie provided actually leads to biography of Charles Winniger, long-time comedian and song-and-dance man. Here’s the key line: “Divorced from wife Blanche in 1951, Charlie subsequently married stage actress-turned-novelist and screenwriter Gertrude Walker whom he originally met on Broadway when he returned to “Show Boat” in 1932 (Gertrude played the role of Lottie).”

Here now is Al Hubin’s reply to Jamie, as sent on to me:

Jamie,

There is a Gertrude W. Winninger in the social security death benefits record, born 4/8/1902, died 6/1995 in Palm Springs, CA. I rather think that’s the author in question, and that I (or my original source) transposed a couple of digits into giving her a birth year of 1920. The fact that Charles Winninger died in Palm Springs seems to clinch it for me. What think ye?

The birth and death dates now having been established with a certainly, it was time, I thought, to take a closer look at the books she wrote.

The link Jamie provided to the “Rara-Avis” group was also the only one that I found that was of any great use. It was a message posted by Etienne Borgers, in response to another’s request for information about her. It reads as follows:

Gertrude Walker

I do not have complete facts or bio, but gathered the following:

– she was born in Ohio (date?)

– studied journalism in Columbus

– published critical articles about poetry and theatrical plays

– published articles about screen stars in magazines

– she was a comedian for a while in Hollywood (theatrical plays) and, later, even a singer

– wrote texts for stand-up comedians (during wartime)

– wrote scripts (and stories) for about 10 films (B-series) during the forties

– wrote for TV serials like The Californians and The New Adventures of Charlie Chan.

As far as I know, she wrote only 3 novels:

+ So Deadly Fair (1947)

+ Diamonds Don’t Burn (1955)

+ The Face of Evil (1978) which seems to be a novelization of her script for Whispering Footsteps (1943)

I read only the first one. Some American critics compared the novel to James Cain’s works at the time of first publishing.

She also wrote some short stories starting during her twenties.

I do not know if this helps.

E. Borgers: Hard-Boiled Mysteries http://www.geocities.com/Athens/6384

There’s some duplication of information here, so please forgive me for that. I haven’t yet looked into the short fiction that Walker may have written. Etienne’s mention of a book entitled The Face of Evil, one that Al Hubin didn’t seem to know about, was what attracted my attention the most. That the date (1978) was the same as the book The Suspect (Major, 1978) made me wonder if perhaps the two books were the same. Neither one showed up for sale on the Internet, but knowing that Bill Pronzini collects the paperbacks published by Major, I emailed him.

In a moment, the results of that inquiry.

In the meantime Jamie had sent me a scan of the jacket blurb for the book he had, the British hardcover, Diamonds Don’t Burn. My thought was that perhaps the British edition was simply retitling of the earlier US book, So Deadly Fair, but Jamie said no, the in book he had mentioned the first one by title. I think the scan is readable, and it looks as though the book itself would be worth reading. Why it was never published in the US is a question as yet unanswered.

An email reply from Etienne Borgers was in essence an apology that he hadn’t any more information about Walker than was posted earlier, but no matter. He had already posted more information about Gertrude Walker than was available anywhere else.

Etienne offered to double check with friends, but by this time, I’d heard back from Bill Pronzini. One of the questions I’d asked him is whether of not The Suspect, the 1978 paperback from Major, actually existed, there being no copies offered for sale on the Internet:

Steve:

Al is surely right that Gertrude W. Winninger and Gertrude Walker were one in the same individual, and that her correct birthdate is 1902, not 1920.

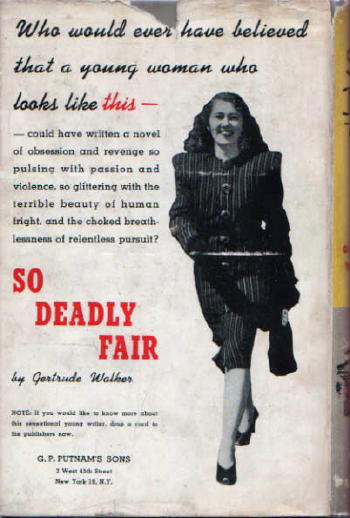

Attached is a photo of Gertrude Walker from the back jacket of her first novel, So Deadly Fair. The accompanying bio calls her “a young woman,” and the photo indicates the same, but my guess is that it’s just publicity hype and the photo an old one.

My copy of the book includes a separate publicity photo in which she looks older, closer to her age at the time the novel was published, 46.

The Suspect does indeed exist; attached are scans of the front and back covers. If it’s a novelization of a 1943 screenplay, it was definitely updated to the 70s milieu. I can’t say for sure, but The Suspect is probably a retitling, either by the author or Major Books, of a manuscript submitted as The Face of Evil. I don’t know of any novel by Walker or anybody else published in 1978 or thereabouts under the latter title.

Diamonds Don’t Burn and So Deadly Fair are definitely separate books. Fair is a sort of hardboiled and frenetic road novel that jumps from Minnesota to New York City and points in between and is narrated by a male protagonist named Walter Johnson.

Best,

Bill

Here’s the front cover of the Major book. It’s obviously a tough book to find. If it’s on your want list, good luck to you!

But what’s more important is the back cover. Check the plot synopsis of the movie Whispering Footsteps up above, and read the back cover again:

Bingo. We have a match.

—

[UPDATE] 03-27-07. Excerpted from an email I received this morning from Victor Berch, suggestions which I’ve accepted with many thanks:

Steve:

You might want to consider adding these to Gertrude Walker’s repertoire:

1935–Mary Burns, Fugitive.

Had a minor acting role in this crime film.

1943–Danger! Women at Work

Described as a homefront comedy, but the hijacking of trucks is part of the plot. GW responsible for the story along with Edgar G. Ulmer.

1945–Behind City Lights.

Described as a crime drama with songs. GW responsible for the adaptation.

1946–My Dog Shep

Described as an animal and youth drama. (involves a kidnapping plot). GW was screenwriter.

Thu 22 Mar 2007

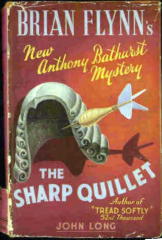

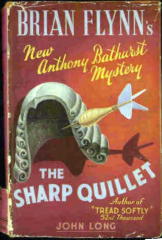

BRIAN FLYNN – The Sharp Quillet. John Long, hardcover, no date stated (1947). No US edition.

You’ll have to fasten your seatbelts, because I’m going to begin this review with a list of Brian Flynn’s mysteries, and it’s going to be a long one. Taken from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, these are the British titles only. Most of these were published only in England, but those preceded by (**) did have US editions.

The detective in every one of these works of crime fiction is a chap named Anthony Bathurst, and since he’s in the book at hand, there will be more about him in a minute. At the present time, there’s no year of death given for his author, Brian Flynn, and I’ll ask a couple of people what they might know about that. First, though, the list of titles:

FLYNN, BRIAN (1885- ) An accountant in government service, a lecturer in Elocution and Speech, an amateur actor.

** The Billiard-Room Mystery (n.) Hamilton 1927.

** The Case of the Black Twenty-Two (n.) Hamilton 1928.

** The Mystery of the Peacock’s Eye (n.) Hamilton 1928.

** The Five Red Fingers (n.) Long 1929.

* Invisible Death (n.) Hamilton 1929.

** The Murders Near Mapleton (n.) Hamilton 1929.

** The Creeping Jenny Mystery (n.) Long 1930.

** Murder En Route (n.) Long 1930.

* The Orange Axe (n.) Long 1931.

* The Triple Bite (n.) Long 1931.

* The Edge of Terror (n.) Long 1932.

* The Padded Door (n.) Long 1932.

* The Spiked Lion (n.) Long 1933.

** The Case of the Purple Calf (n.) Long 1934.

* The Horn (n.) Long 1934.

* The League of Matthias (n.) Long 1934.

* Tragedy at Trinket (n.) Nelson 1934.

* The Sussex Cuckoo (n.) Long 1935.

** Fear and Trembling (n.) Long 1936.

* The Fortescue Candle (n.) Long 1936.

** Tread Softly (n.) Long 1937.

* Cold Evil (n.) Long 1938.

* The Ebony Stag (n.) Long 1938.

** Black Edged (n.) Long 1939.

* The Case of the Faithful Heart (n.) Long 1939.

* The Case of the Painted Ladies (n.) Long 1940.

* They Never Came Back (n.) Long 1940.

* Such Bright Disguises (n.) Long 1941.

* Glittering Prizes (n.) Long 1942.

* Reverse the Charges (n.) Long 1943.

* The Grim Maiden (n.) Long 1944.

* The Case of Elymas the Sorcerer (n.) Long 1945.

* Conspiracy at Angel (n.) Long 1947.

* Exit Sir John (n.) Long 1947.

* The Sharp Quillet (n.) Long 1947.

* The Swinging Death (n.) Long 1948.

* Men for Pieces (n.) Long 1949.

* Black Agent (n.) Long 1950.

* And Cauldron Bubble (n.) Long 1951.

* Where There Was Smoke (n.) Long 1951.

* The Ring of Innocent (n.) Long 1952.

* The Running Nun (n.) Long 1952.

* The Seventh Sign (n.) Long 1952.

* Out of the Dusk (n.) Long 1953.

* The Doll’s Done Dancing (n.) Long 1954.

* The Feet of Death (n.) Long 1954.

* The Mirador Collection (n.) Long 1955.

* The Shaking Spear (n.) Long 1955.

* The Dice Are Dark (n.) Long 1956.

* The Toy Lamb (n.) Long 1956.

* The Hands of Justice (n.) Long 1957.

* The Wife Who Disappeared (n.) Long 1957.

* The Nine Cuts (n.) Long 1958.

* The Saints Are Sinister (n.) Long 1958.

It certainly isn’t likely to mean anything, but Mr. Flynn didn’t do anything like slow down toward the end of his writing career, did he? Sixteen books between 1951 and 1958, after reaching the age of 66. One might guess that he’d retired from his day job (see above).

Heading off to see what Google says, with the author having such a common name, it was quickly discovered that any kind of effective search was going to have to be done on Bathurst the character, rather than Brian Flynn the author. And — there’s nothing to be found. All that comes up are books by Flynn for sale from various dealers’ catalogues. Other than what Al Hubin has provided for him in his entry in CFIV, there’s not a single website providing information on either author or character to be found, not one citation, nothing. (That’s about to change, however, isn’t it?)

Obviously Brian Flynn was no rival to Agatha Christie, but why has he so drastically dropped out of sight? Were his books so indifferently or badly written? On the basis of one example, I’d say no, but on the basis of the very same example, I’d have to agree (if asked) that the style of story is outdated, or at least its ending is. The detective work is essentially sound, although the reader is not made privy to all that Anthony Bathurst knows.

And I see that I’m writing this review wrong end to, and so to right this wrong, let me jump back to the prologue, in which a defendant in court is sentenced to die (and does), but so does the entire jury, all twelve individuals, wiped out in a rocket bomb attack and preceding the defendant to death. I don’t think I’ve ever read that in a book before!

At some length of time later, more deaths begin occurring, the first being that of Nicholas Flagon, a justice on the panel that denied the appeal of the defendant in the prologue. Which is why I so strongly dislike prologues, if I may bring this small rant out into the open one more time. I hate knowing facts and information that the detectives on the case do not have. I don’t enjoy it, I don’t like watching bright policeman and even brighter private detectives work their way through investigations on a case that doesn’t really begin (for me) until they’ve caught up to where I already am, due to the wisdom imparted to me when I didn’t really want it.

End of rant. Dr. Harradine and the local Inspector, a man named Catchpole, are the first on the scene. Tied around the shaft of the dart that has just killed its victim is a slip of paper that says, “A nice sharp quillet. Ay!”

Off to the dictionary go I, and wouldn’t you? A quillet is not a small pen, as suggested on page 30, but: “An evasion. In French ‘pleadings’ each separate allegation in the plaintiff’s charge, and every distinct plea in the defendant’s answer used to begin with qu’il est; whence our quillet, to signify a false charge, or an evasive answer.” Emphasis on “a false charge.”

The policemen on the case, and Anthony Bathurst, do not get back to this point until page 111, so OK, I did some investigating on my own and learned something before they did. I’m not contradicting myself, in terms of what I said about prologues just moments before. I think that this is acceptable, isn’t it?

As for Anthony Lotherington Bathurst, he enters the scene on page 50, when he’s asked by Commissioner Kemble of Scotland Yard to add his expertise to the men on the ground (so to speak) where the victim was killed, their efforts seemingly going nowhere. Bathurst agrees — there’s nothing like a good solid case of mystery to work on — and together with Chief Detective-Inspector MacMorran he makes his way to the otherwise sleepy village of Quiddington St. Phillip, just in time for another death to have occurred.

From this you may thinking that Bathurst is just another policeman highly regarded for solving crimes, but he is not. He’s a private detective. PI’s in the US have seldom had this kind of respect for their abilities as those who plied their trade in England. Perhaps Bathurst should be called a private inquiry agent, along the lines of a Sherlock Holmes. The name of the profession makes all of the difference in the world.

By page 113 Bathurst has decided that he knows who the killer is, but (of course) he has no proof. On page 174 he explains, but he fudges a little, in my opinion, for back on page 113, as he relates it later, all he had were the same four suspects that the reader had, with only a high probability as to which of the four it was likely to be.

Coming in between is a matter of filling in of the details, plus a long stretch of about 25 pages’ worth of unadulterated thriller-like behavior in which the next projected victim of the killer must be protected and the reader (literally) comes along only for the ride. Which is to say that if the reader were kept informed of what is happening, he (or she) would also know who it was the victim is being protected against.

If that makes any sense at all. In any case, everything works out fine, and handshakes all around are the order of day. While Flynn was no rival to Christie or any of the other names you’re a lot more familiar with, in my opinion neither does he deserve to be forgotten. There are some scenes in this book, well-described, that will linger in memory for a while, including the prologue, and yes, I’d read another adventure of Mr. Bathurst at any place and time that you say, other than the break of dawn.

— January 2007

Wed 21 Mar 2007

Noted comic book writer Arnold Drake died last week at the age of 83. Among his many accomplishments in that particular field were the stories he wrote for “Batman” in that hero’s early days; he was also the creator of the supernatural hero “Deadman” and the action team called “The Doom Patrol.”

Of the many comic book sites where the news of his passing was announced, Mark Evanier’s blog, with his personal insight into Mr. Drake’s career, may be the single best place on the net to learn more.

It was author Edward D. Hoch, however, who first spotted Arnold Drake’s name as being included in Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV. In an email sent first to Marvin Lachman, however, he wondered if it was indeed the same Arnold Drake. It was, as it turns out, the same man.

The entry is small, but it’s there. Here it is, as slightly revised over the last couple of days. After an afternoon of discussion, there has been an addition made, but we’ll get to that in a minute:

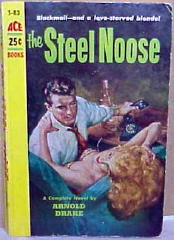

DRAKE, ARNOLD (Jack) 1924-2007. Joint pseudonym with Leslie Waller, 1923- , q.v.: Drake Waller, q.v.

The Steel Noose (Ace, 1954, pbo) [New York City, NY]

You may not be able to read the small print on the cover. It says along the top: “Blackmail – and a love-starved blonde!” The leading character is a hardboiled gossip columnist named Boyd McGee. (That there was only the one novel meant that McGee could never be upgraded to a series character.)

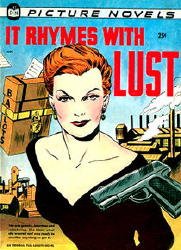

An new addition to Mr. Drake’s entry in CFIV was mentioned earlier. In 1950 Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller teamed up to produce what is generally considered to be the first “graphic novel,” a digest-sized paperback entitled It Rhymes with Lust. The interior black-and-white art was by the highly collected GGA artist, Matt Baker. (For the uninitiated, GGA = Good Girl Art.)

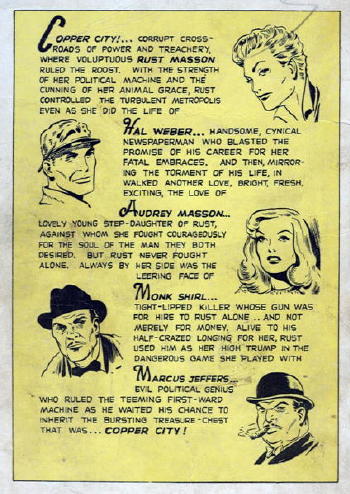

Is It Rhymes with Lust a crime novel? When I found my copy and skimmed through it, I described it to Al Hubin thusly: “The lady on the cover wants to run a copper town (her name is Rust) and she hires thugs and at least one killer (with a machine gun) to keep the miners in line; and there’s graft involved, and the cops.”

Machine guns and graft do not necessarily make a novel a work of crime fiction, of course. In this case they are incidental to the plot, and not the heart of the story itself. The back cover will make this clearer, I believe:

Marginal works like this are already included, but indicated by a dash, and in the Addenda #12 to the Revised Edition of CFIV, that’s how it’s now given:

WALLER, DRAKE Joint pseudonym of Leslie Waller, 1923- , q.v., and Arnold (Jack) Drake, 1924-2007, q.v.

-It Rhymes with Lust. St. John pb, 1950 (Graphic novel.)

It’s a minor footnote in the field of crime fiction, but as was indicated earlier, it made history in the world of comic books as the very first graphic novel. If you check the shelves at your favorite chain bookstore, you will see how large a statement that is.

Wed 21 Mar 2007

Hi Steve —

Just wanted to thank you for your recent M*F post about the Michael Shayne movies coming to DVD this week. The photos of all the actors who played the part are much appreciated, as is your support for my Kenneth Tobey idea. If only … As for the Sleepers West/Sleepers East business, your guess is as good as mine. I look forward to your reviews of the films.

www.VinceKeenan.com

Pop culture, high and low, past and present.

One day at a time.

Vince

I don’t know if you’d agree that the portrait of Shayne on the paperback covers is definitive, but since those are the Shayne’s that I read back when I was reading them, that’s the image that comes to mind when I think of Mike Shayne.

But, and it’s a big “but,” Jeff Chandler played Michael Shayne for a couple of years on the radio. Maybe I should do a follow-up and include his picture? Or not, since nobody ever saw this face in the role … ???

Steve,

I suppose I do think of that portrait of Shayne as definitive. It’s on the cover of every one of the novels I’ve ever read, and it’s featured prominently on all of the websites devoted to the character. Not that that necessarily means anything. A big reason why Kenneth Tobey struck me as perfect for the role is that he has red hair — which, of course, you couldn’t see in black-and-white.

Or on the radio, for that matter. Jeff Chandler still doesn’t strike me as quite right, either, but then I suppose I should listen to an episode or two of the show before deciding. Have you heard any of them? That is a great photo of Chandler …

I picked up the Shayne discs yesterday. Fox has put a dandy package together. Nice extras throughout. Last night I watched the first film in the series as well as a 17-minute feature on the history of the character. I feel bad that I ever implied anything negative about Lloyd Nolan, because he’s dynamite in the part. It’s not the Mike Shayne from the books — he’s more of a generic big-city P.I. — but Nolan fills out the role beautifully. I think this series will be rightly reevaluated in the wake of this release.

Vince

You asked and so here it is — a link to a Michael Shayne radio show with Jeff Chandler. This one’s from July 22, 1948, if the source I got it from is correct. The series is called The New Adventures of Michael Shayne, and was on the Mutual network from 1948 to 1950. An earlier series with Wally Maher as the star was on ABC between 1944 and 1947, and there was a later one on ABC again for the 1952-53 season. The star was Donald Curtis, or so I’m told, replaced by Robert Sterling.

The episode that the link leads to is #5 in the Jeff Chandler series, titled “The Case of the Hunted Bride.” In my opinion this was one of the better PI shows on the radio, and I think Chandler was very effective in the part. Whether he’s “Mike Shayne” or not is a whole other kettle of fish.

As for Lloyd Nolan, after your comments, I’m all the more anxious to get my set in the mail. If I’ve seen any of these Shayne films, it hasn’t been for 50 years, so who remembers?

Steve,

…As you might have guessed, I’ll be writing up a more in-depth look at the DVD set once I’ve watched all four films. At this rate, it will probably be sometime this weekend.

— And that’s it from here. Be sure to be looking for more of Vince’s comments on the Mike Shayne films — not here, but over on his own website. I’ll keep you posted. — Steve

« Previous Page — Next Page »