March 2007

Monthly Archive

Wed 21 Mar 2007

After posting my comments on

Charles Einstein after his death, I mentioned to Bill Pronzini that as I remembered it, he was the one who’d told me to read Einstein’s first crime novel,

The Bloody Spur. We’re speaking 30 to 35 years ago, mind you. Here’s Bill’s reply:

Re Charles Einstein: I may in fact have recommended The Bloody Spur to you; I’ve been known to champion it. Really excellent novel made into an equally excellent film. Nowhere to Run, the film made from Blackjack Hijack, is surprisingly good for a made-for-TV flick; Marcia and I watched it recently and were impressed by the quality of the script, the depth of characterization, and the performances. David Janssen, in one of his last films, is outstanding.

Re the Mike Shayne movies: I have a VHS tape of The Man Who Wouldn’t Die. Haven’t watched it a while, but as I recall, the story is only loosely based on Rawson’s No Coffin for a Corpse, using some of the novel’s trappings and plot elements but not the clever “impossible” gimmick. It’s not among the best of the celluloid Shaynes: too talky, too wisecracky and silly, though it does have some effective H’wood atmospherics (howling storm, weird old house, grave-digging in the dead of night, etc.) “Gus, the Great Merlini” does indeed make a brief appearance; the character runs a magic shop that Shayne visits for information.

Tue 20 Mar 2007

Jiro Kimura, who has now owned and operated The Gumshoe Site for 11 years, reports that legal-thriller writer Lelia Kelly lost a long battle with breast cancer on March 13th. She was only 48.

According to information on her website, Ms. Kelly, a banker for 15 years, left the world of finance in 1998 and turned to writing instead. Her first two books are included in Crime Fiction IV: 1749-2000, by Allen J. Hubin. A third title has since been added to her bibliography, all in her Atlanta-based Laura Chastain series:

KELLY, LELIA (1958-2007)

* * Presumption of Guilt (NYC & London: Kensington, 1998, hc)

* * False Witness (Kensington, 2000, hc)

* * Officer of the Court (Kensington, 2001, pbo)

In her first appearance, Presumption of Guilt, Laura Chastain is a senior associate at a prestigious Atlanta law firm, but when the situation arises, she is surprised to discover she is good at criminal defense work, which is far from being a specialty of the firm.

According to the Booklist review of the book: “After she successfully defends the son of a corporate client against highly publicized rape charges, an Atlanta policeman strolls into her office, asking for help with charges that he killed a suspected child molester in custody at a police station. Despite management’s misgivings, Laura’s supervisor, poetry-spouting Tom Bailey, supports her desire to take the tabloid-ready, racially divisive brutality case.”

By the time False Witness appeared, Laura had become an assistant DA, giving up her former (and much higher paying) position. Publishers Weekly described the story thusly: “Wealthy Christine Stanley has been murdered in her upscale Atlanta residence, leaving behind two shocked and bewildered children. Suspicion falls upon her husband, financial manager James T. Stanley, even though his alibi seems airtight (he was out of town on business).” Laura is also said to have a “a sweet, low-key romance.”

In Officer of the Court, according to one reviewer on Amazon.com: “Lelia Kelly’s heroine once more surprises the reader by not following any pre-established rules of the game as a prosecutor. Kelly presents the interesting point of view, of what a prosecutor faces, when he/she knows the person on trial is really innocent of the crime. Chastain follows her own moral code, and not necessarily what the law, or the pattern of activities we have allowed to surround the law, dictates.” As of this date, all six reviewers on Amazon have given the book the maximum five stars out of five.

A fourth book was promised, but in a letter she posted on her website in October 2002, Ms. Kelly saddened her readers by saying that her cancer had returned. There would be a wait, she said, before Laura’s next case could be told. Sadly, it appears that the next chapter was not to be.

Tue 20 Mar 2007

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

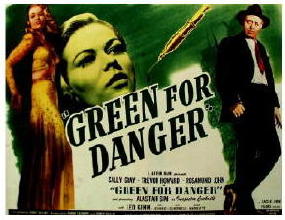

The centenaries have come thick and fast lately: Woolrich in 2003, Fred Dannay and Manny Lee in ‘05, John Dickson Carr last year. Now we celebrate one of the great masters of English detective fiction, Christianna Brand. She was born Mary Christianna Milne in Malaya – on December 17th of, as if you hadn’t guessed, 1907 – began writing whodunits a couple of years after the start of World War II, and is best known as the author of Green for Danger (1944), a classic of fair-play detection set in a military hospital in Kent during the Blitz.

I got to meet her when she was around 70 and quickly discovered that she was as perfect in the role of the dotty English lady as was Basil Rathbone playing Holmes. Who can ever forget the MWA dinner where she was asked to present one of the Edgar awards? “The nominees are: Emily Smith, James Quackenbush….Hahaha, Quackenbush, what a funny name!” The audience, except perhaps for poor Quackenbush, was left rolling in the aisles.

On my first visit to England, to serve as an expert witness at a trial in the Old Bailey during the summer of 1979, Christianna and her husband Roland Lewis, one of England’s top ear-nose-and-throat surgeons, took me to dinner at Simpson’s in the Strand, the famous old eatery where one tips the server who carves your roast beef tableside. A few years later I edited Buffet for Unwelcome Guests (1983), the first collection of her short stories published in the U.S. On my next visit to England after the book came out I could hardly lift my suitcases, which were packed to bursting with copies for her. She died on March 11, 1988, and everyone who knew her still misses her.

The 1946 movie version of Green for Danger, starring Alastair Sim as the insufferable Inspector Cockrill and featuring superb English actors like Trevor Howard and Leo Genn, has long been considered one of the finest pure detective films ever made, but it’s been very hard to access over here until just a month or so ago when, in a miracle of perfect timing, it was released on DVD. If you love the classic whodunit but have never seen the film nor read the book, you have a double treat in store.

The tale of fair-play detection has become a dying art, but each of two recent issues of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine has featured at least one specimen worthy of the Golden Age. Jon L. Breen’s “The Missing Elevator Puzzle” (February 2007) is quite simply the finest short whodunit with an academic setting that I can recall reading, with a puzzle that might have fazed Ellery himself: Why was a visitor to the campus, just before being murdered, searching for the elevator in a building that had none?

“The Book Case” (May 2007) by Dale Andrews and Kurt Sercu not only has two authors like the Queen books themselves but returns to center stage their most famous detective, physically frail but mentally spry at age 100, as he tackles a murder with a dying message composed of copies of his own novels. Readers who aren’t well up on those novels are likely to get lost in this tale, but if you’re at home in the canon you’ll have a high old time trying to beat the centenarian sleuth to the solution.

In most centenary celebrations the subject is dead, but there’s one coming up in just a few months where the honoree is still with us – and, so I’m told, doing well for a 99-year-old. He claims to have written a number of short whodunits published under a pseudonym in his student years but his real significance for us lies in his extensive writing about the genre over several decades and in his connection with the supreme master of pure suspense fiction.

I am referring of course to Jacques Barzun, distinguished professor at Columbia University, co-author of the massive Catalogue of Crime, and, in the early 1920s, Columbia classmate of Cornell Woolrich, who quit college in third year when his first novel sold.

My first contact with Dr. Barzun was back in the late Sixties when I arranged to include one of his essays in my anthology The Mystery Writer’s Art (1970). In April 1970, while I was working on Nightwebs (1971), my first collection of Woolrich stories, he invited me to his Columbia office and we spent most of an afternoon talking about what the university was like almost half a century earlier when he and Woolrich were undergraduates together and sat next to each other for several courses.

We corresponded off and on for several years. After translating from the French (a language I had never studied) an essay about Georges Simenon’s pre-Maigret crime novels, I presumed on my acquaintanceship with Barzun and asked him to look over my draft before I sent it in to The Armchair Detective. He made many small corrections, one of which I still vividly remember: I had rendered a line from an early Simenon as “Marc’s bottle was empty” which he changed to “The bottle of marc was empty,” pointing out to me that marc is a cheap French brandy. But on the whole he was hugely pleased with my translation, saying that he was “truly amazed” that I had done it without ever having taken a French course and that it was “certainly better than much advanced student work in a Romance Language Department.”

In the early Eighties I became involved with Nacht Ohne Morgen (Night Without Morning), a documentary on Woolrich for German TV, and arranged for the director, Christian Bauer, to interview Barzun. They talked for almost an hour but only about a minute of footage found its way into the finished film. I obtained an audiotape of the entire interview and quoted from it extensively in my own Woolrich book First You Dream, Then You Die (1988). If Jacques Barzun had not been still alive and well and blessed with a vivid memory, we would know so much less about a key period in Woolrich’s life. For that gift to the genre and for countless others, merci beaucoup. May his hundredth birthday be a joyous one and not his last.

Mon 19 Mar 2007

THE BAT, by Mary Roberts Rinehart

Mary Roberts Rinehart’s character called “The Bat” appeared in many formats over the years. Not only did “The Bat” make a lasting impression and appear in many venues, but Bob Kane, creator of the second most famous comic book character, the Batman, has been quoted as saying that the inspiration for his hero came from “actor Douglas Fairbanks’ movie portrayal of Zorro, and author Mary Rinehart’s mysterious villain ‘The Bat.’”

This post has been put together from a variety of sources, the first being Michael Grost’s Classic Mystery and Detection website, from which is gleaned the following information about the early career of mystery author Mary Roberts Rinehart:

The Early Novels 1904-1908

The career of Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1957) can be broken up into a series of phases. The first was her pulp period (1904-1908), where she wrote her first three mystery novels and a mountain of very short stories. These stories have never been collected in book form, and are inaccessible today. The first two novels are classics, however, and are probably her best works in the novel form.

The Man in Lower Ten (1906) and The Circular Staircase (1907) are the earliest works by any American author to be still in print as works of entertainment, not as “classics” or “literature.” These novels, which combine mystery and adventure, show Rinehart’s tremendously vivid powers as a storyteller.

From the same page, but skipping over a few sections:

The Bat

The Bat is a stage adaptation of Rinehart’s The Circular Staircase, written in collaboration with Avery Hopwood, the writer of popular Broadway comedies with whom Rinehart had collaborated before. The Bat introduced some new plot complexities into the original novel, especially a master criminal known as “The Bat.” It also includes plot elements reminiscent of her first Saturday Evening Post story, “The Borrowed House” (1909). The Bat shows Rinehart at the height of her powers, and in fact is her greatest work. A work of great formal complexity, The Bat is one of the few mystery stage plays to have the dense plotting of a Golden Age detective novel. Moreover, the formal properties of the stage medium are completely interwoven with the mystery plot, to form intricate, beautiful patterns of plot and staging of dazzling complexity.

According to the online Broadway database, The Bat ran for 867 performances between August 23, 1920 and September 1922.

Film director Roland West next made two versions of the play, a silent film The Bat (1926), and a sound film The Bat Whispers (1930).

Following the links will lead you to the IMDB pages for each.

His discussion is far too lengthy to repeat here, but Mike Grost goes into considerable detail in discussing director Roland West’s cinematic techniques in both of these movies, plus a number of his other films. If you’re interested in the early days of movie making, Mike’s website once again is well worth the visit.

Returning to the play itself, Mike continues by saying:

Rinehart and Hopwood’s play can be found in the anthology

Famous Plays of Crime and Detection (1946), edited by Van H. Cartmell and Bennett Cerf, along with other outstanding plays of its era. (This book also contains good plays by Roi Cooper Megrue, Elmer Rice, George M. Cohan, and John Willard.) In 1926, a novelization of

The Bat appeared, apparently written by poet Stephen Vincent Benét with little input from Rinehart. This novel version usually appears in paperback under Rinehart’s name, without any mention of Hopwood or Benét. I read this novelized version first, and confess I prefer it to the script of the play itself.

It should also be noted that the play itself was later published by French, in a 1932 softcover edition.

In 1959 The Bat was once again made into a film, this one starring Vincent Price and Agnes Morehead. Of this version, one viewer says: “I found this to be an inventive and disingenuous endeavor full of red-herrings and wrong turns. Figure this one out for yourself. Puzzle the clues, weed out the characters set here as distractions, look past the deliberate contrivances and solve the mystery on your own.”

By total coincidence, the way coincidences happen, as I was in the process of tracking down the details of all these various incarnations of the character, author Mary Reed sent me the following review of The Bat, the novel based on the play. I think it’s great when a plan comes together like this.

Review of THE BAT: The Novel, by Mary Reed

Everyone in the city, from millionaires to the shady citizens of the underworld, goes in fear of The Bat, a cold-blooded loner whose crimes range from jewel theft to murder and whose calling card is a drawing or some other form of expression of bathood.

We meet wealthy, elderly, and independent spinster Miss Cornelia Van Gorder, scion of a noble family and the last of the line. An adventurous spirit, at 65 and comfortably situated, she still longs for a bit of an adventure. It maddens her to think of the sensational experiences she is missing as she contemplates that “…out in the world people were murdering and robbing each other, floating over Niagara Falls in barrels, rescuing children from burning houses, taming tigers, going to Africa to hunt gorillas, doing all sorts of exciting things!” Why, she’d love to have a stab at catching The Bat!

Her wish is granted when she takes a house in the country for the summer and discovers it is located some twenty miles from an area where The Bat had committed three crimes. She is soon in the thick of mysterious events, including anonymous threatening letters, lights failing, a face at the window, and Lizzie Allen, her personal maid for decades, convinced she saw a strange man on the stairs. Most of the servants decamp, leaving Miss Van Gorder to manage with just a butler and Lizzie.

More characters appear: Miss Van Gorder’s niece Dale Ogden, Brooks, the new gardener, local medical man Dr Wells, Detective Anderson, and Richard Fleming, nephew of Courtleigh Fleming, deceased owner of the house and once president of a bank which has just failed. There is talk Mr Bailey, its cashier, has stolen over a million dollars. A man is shot and an unknown party is deduced to be hiding somewhere on the rambling premises. More than one person in the house is concealing facts, and the rising storm outside underlines the increasing fear and tension within.

Who is trying to scare Miss Van Gorder away and why? What if anything did Lizzie see on the staircase? Are any of the strange goings-on connected with the missing money? Who fired the shot? There is much flitting in and out of the doors and windows of a living room lit most of the time only by candle and firelight before everything is cleared up.

The Bat is an excellent example of an old dark house mystery, with enough obfuscation to keep the reader guessing, although one or two surprises are less well concealed. The menacing atmosphere events create in the house is conveyed and sustained well. I found it a light, diverting read which held the interest without taxing the attention too much. The Bat is an excellent cold-night-outside read, and indeed, although I know whodunit, I would not mind seeing the play!

Etext at http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext00/thbat10.txt

Mon 19 Mar 2007

Just a quick note to let you know that the covers to the Phoenix Press mysteries are now complete through 1946. Check out the latest additions here.

Sat 17 Mar 2007

PATRICIA SPRINKLE – Death on a Family Tree

Avon, paperback original; 1st printing, January 2007.

Here’s an author who’s been writing mysteries for quite a while, and (this may come as no surprise) this is the first one of hers that I’ve read. From the author’s website and a few other sources, including Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, I’ve come up with what I believe is a list of the books she’s done. Note that in some cases her byline is Patricia Houck Sprinkle.

Sheila Travis Series: In Murder at Markham Sheila has been recently widowed and is working for a diplomatic training center in Chicago. Assisting her in solving crimes is her Aunt Mary, who hails from Atlanta, where Sheila frequently goes back to visit. In the third book in the series, Sheila moves back there permanently.

Murder at Markham. St. Martin’s, hc, October 1988. Worldwide, pb, October 1992. Silver Dagger Mysteries, trade pb, revised, December 2001.

Murder in the Charleston Manner. St. Martin’s, hc, May 1990. Worldwide, pb, April 1993. Silver Dagger Mysteries, trade pb, August 2003.

Murder on Peachtree Street. St. Martin’s, hc, April 1991. Worldwide, pb, October 1993.

Somebody’s Dead in Snellville. St. Martin’s, hc, August 1992. Worldwide, pb, July 1994.

Death of a Dunwoody Matron. Doubleday, hc, April 1993. Bantam, pb, August 1994. Bella Rosa Books, trade pb, December 2005.

A Mystery Bred in Buckham. Bantam, pbo, October 1994. Bella Rosa Books, trade pb, January 2007.

Deadly Secrets on the St. Johns. Bantam, pbo, August 1995. [Note: This book is extremely scarce. There are only five copies offered for sale on Amazon, for example, with the lowest price being $44.50 for a copy in “good” condition.]

MacLaren Yarbrough Series: In the first book in the series, MacLaren is a wife of Judge Joe Riddley Yarbrough, a magistrate for the state of Georgia. In the second book, after her husband is shot, and two other people are murdered, MacLaren not only solves the crimes, but she takes over his position on the bench as well. After the first two novels were published by a Christian press, the rest of the series were published as mass-market paperback originals.

When Did We Lose Harriet? Zondervan, pbo, November 1997.

But Why Shoot the Magistrate? Zondervan, pbo, September 1998.

Who Invited the Dead Man? Signet, pbo, July 2002.

Who Left That Body in the Rain? Signet, pbo, December 2002.

Who Let That Killer in the House? Signet, pbo, October 2003.

When Will the Dead Lady Sing? Signet, pb, June 2004.

Who Killed the Queen of Clubs? Signet, pbo, March 2005.

Did You Declare the Corpse? Signet, pbo, February 2006.

Guess Who’s Coming to Die? Signet, pbo, February 2007.

The Family Tree Series:

Death on the Family Tree. Avon, pbo, Jan 2007.

Sins of the Fathers. Coming in October 2007.

From Ms. Sprinkle’s website she says about her work in progress: “Now I am deep in the tenth, and probably last, MacLaren Yarbrough mystery, What Are You Wearing To Die?” Which strongly suggests, of course, that she’s in the midst of shifting gears. Future mystery adventures will be concentrating Katharine Murray, a middle-aged Atlanta housewife who’s well-off and somewhat pampered, and whose first brush with crime in any form Death on the Family Tree is.

The book begins on her 46th birthday, which she’s spending alone and which, unbeknownst to her, is her last day in her old comfortable life. Her children have moved out, and her husband Tom is out of town. Opening a box left to her by her recently departed Aunt Lucy, she finds two unusual items in among the junk: an ugly bronze necklace dating from the mid-1800s from Halstatt, Austria, and a diary, written in German and dating from a far more recent 1937.

As she begins some genealogical researching she soon discovers relatives that she never knew she had, that there are secrets in her family she had never been told about, and that the diary means something to someone who will stop at nothing to possess it. You may have guessed that about the latter.

Also re-entering her life is a former boy friend, one she’d unceremoniously dumped before she married Tom, who is blissfully unaware that his absence in this crucially important time is his wife’s life is as serious as it is. Make that totally oblivious. (Speaking from a man’s point of view, he is a blithering idiot, and if he doesn’t watch out, he will deserve what he will most certainly get in the next book in the series.)

Forgive me. I had to get that out of my system. It takes a while for all of Katharine’s family, her friends, and her friends’ families straightened out in the reader’s mind, and there surely are a lot of them, family, friends and relatives, that is. Katharine herself is prone to talking too much to all of them about her finds, and almost everyone else she meets. This was a tendency that this reader found almost intolerable, especially when all of this excessive talking leads to her being chased by cars, break-ins at her home, and eventually worse: several murders.

It is soon clear (or it was to this reader) who is responsible for all of this nefarious activity, but Katharine, who even toward the end of the book still has not learned much about this Brand New World she is in, walks straight into the hands of the enemy, as if without a thought in her head.

I don’t usually start yelling at characters in the mystery fiction I am reading, but I did this time. Perhaps that means that I cared? Perhaps so.

Sat 17 Mar 2007

If I followed his instructions correctly, my son-in-law says the M*F blog “is now mobile ready. Access mysteryfile.com/blog/ from your web capable mobile device and you’ll get a specially formatted page with all the same info.”

I’d try it out myself, but I don’t even own a cell phone yet. If it works where you are, let me know.

Sat 17 Mar 2007

I don’t know if I can do this, but I’m going to give it a try. I recently came across an episode of the 1940s Ellery Queen radio program that I hadn’t heard before, and maybe I can make it available to you here. The sound isn’t very good, but I think it’s listenable.

Clicking on this link should start it playing. You can also download it and play it later. If all goes well.

[UPDATE] 03-18-07. Not having been informed of any difficulties, I’m assuming that everyone who’d like to has been able to listen. I shall, more than likely, do this again. For example, I’ve just come across an Australian radio series called Carter Brown Mysteries. As part of the introduction to the first story, interviewed is none other than Carter Brown himself. I’ll make it available here as soon as possible.

As for “The Income Tax Robbery,” here is what Francis M. “Mike” Nevins, the world’s leading expert on Ellery Queen, has had to say, as excerpted from a couple of emails:

“I won’t be able to listen to that EQ radio play till the next time I go in to school, but the original air dates were March 12 and 14, 1942. I was told years ago that a cassette copy was available for listening at the Library of Congress. That copy I assume is the source of whatever you came across.”

During 1942, the Ellery Queen program was broadcast twice, the earlier date for West Coast listeners, the second date for those on the East Coast. The stories were the same but different “armchair detectives” were used, either in the studio or on call by telephone. The programs stopped before the ending so that these guests could be asked to solve the crime at the same time that Ellery did. (They were often correct.) Scripts were by Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. The cast included Carlton Young as EQ, Santos Ortega as Inspector Queen, Ted de Corsia as Sgt. Velie, and Marian Shockley as Nikki Porter.

Here’s Mike again, in an email I received today:

“I came down to school for a while this morning and played ‘The Income Tax Robbery.’ What you have is clearly the East Coast version, broadcast March 14, 1942. The full name of the mayor who served as guest armchair detective by telephone was Howard W. Jackson.”

[UPDATE] 07-22-07. I never did get around to transcribing that on-the-air interview with Carter Brown. This morning, though, Toni Johnson-Woods came to my rescue. She posted a comment to this blog entry which I’ve upgraded to a new post of its own. You’ll find it here, along with MP3 links to the complete first story of the series, a four-parter called “Call for a Columnist.” Toni also supplied me with a link to another episode entitled “Swimsuit Sweetheart.” Go take a look. And listen.

Fri 16 Mar 2007

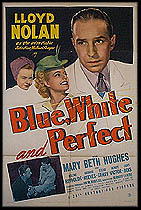

Vince Keenan, my mystical master in all matters movie-wise, recently mentioned on his blog a soon-to-released boxed set of DVDs that is simply said, a must-not-miss. Available on March 20th is a boxed set of four Michael Shayne films from the forties that I have not seen in a long, long time, if ever.

All four of them star Lloyd Nolan, whom you’d never go too far wrong by casting him as a semi-down-on-his heels private eye, but as Vince says, the perfect fellow would have been Ken Tobey.

Contained in this set are:

Michael Shayne, Private Detective. 1940. This is one of the very few Mike Shayne movies that was actually based on a Mike Shayne novel. I’ve not checked to see how many of the rest of them were, but in this case it was Dividend on Death (Holt, 1939). [Note that Crime Fiction IV is in error on this point, and a statement to that effect has been made in the online Addenda to the Revised Edition, Part 12.]

The Man Who Wouldn’t Die. 1942. Credit is given to the Brett Halliday characters, but the novel it’s based on was Clayton Rawson’s No Coffin for the Corpse, a classic Great Merlini “locked room” mystery. Having never seen this film, and I’m very eager to, I don’t know how much of the plot line has been preserved, but for what it’s worth, way down in the IMBD credits is Charles Irwin as “Gus, the Great Merlini” (uncredited).

Sleepers West. 1941. This one’s based on Frederick Nebel’s mystery novel, Sleepers East. I don’t know. You tell me.

Blue, White and Perfect. 1942. Credit for the characters was once again given to Brett Halliday, but the story the movie’s based on was actually written by Borden Chase. It didn’t appear in book form until it came out as a 1947 digest paperback entitled Diamonds of Death (Hart K-2). The first appearance of the story was probably as a serial in one of the pulp fiction magazines in the 1930s.

As much as I’d like to, I can’t review the movies now, but the odds are that I will, as soon as I’m able. Let’s go back to Vince’s comment that the perfect gent to play Michael Shayne would be Ken Tobey. (Looking back, I see that I’ve been assuming all along that you know who Mike Shayne is, and who Brett Halliday was. I didn’t intend to go into it here, and I won’t, but what I will do to send you to Kevin Burton Smith’s Thrilling Detective PI site, and trust to your good judgment to come back. It’s a gamble on my part, because I know from experience that you could easily get lost and spend days on end there, if you’re not careful.)

Here’s a picture of Mike Shayne that was used on the covers of tons of 1950s Dell paperbacks. I’m not sure, but I suspect that the artist responsible was Robert Stanley. I’m sorry that it’s rather small, but it was only used in the corner of the covers.

Now here’s one of Lloyd Nolan. I can’t at the moment guarantee that this comes from one of the Mike Shayne movies, but I think it does. It’s the right vintage, at least:

Maybe he needs a hat and a cigarette drooping out of his lip, but I don’t see a resemblance.

Here’s one of Hugh Beaumont. Before he became famous as Beaver’s dad, Hugh Beaumont remained fairly non-famous by playing the part of Mike Shayne in five films cranked out for PRC between 1946 and 1947. (Will these show up on DVD some day?)

He isn’t bad, but it’s tough to tell, since all we see in this photo is his profile, but if you think about the Beaver’s show, and think Mike Shayne, do you get the same disconnect that I do?

Mike Shayne was also the star of aTV show for one season on NBC, 1960-61. I was away at school then, and didn’t have time for TV, so I never saw it. I believe some of the shows are available on DVD, and if so, that’s one more item I’ll have to addto my next Amazon purchase. I also just realized that I didn’t mention that Richard Denning was the star. Here’s his likeness:

Do you know what? As the years went on, I think the producers and the casting personnel were getting closer.

Vince said Kenneth Tobey was the man, though, and I’m in full agreement. What do you think?

[UPDATE] 03-19-07. A few typos have been corrected in the essay above, and several questions of a bibliographic nature have been answered, requiring a bit of revising here and there. This is now (um) the current version. Thanks again to Vince Keenan for allowing me to play on his ground.

Fri 16 Mar 2007

Jamie Sturgeon recently sent me a couple of emails about some of the obscure authors who’ve been discussed here. I’ve been remiss in not posting them earlier, but here at last they are. The first one concerns the inquiry about Arthur J. Rees.

Steve,

I wonder if Arthur J. Rees emigrated to Australia to live with his two sisters and died there? His last book, The Single Clue, although set in England, was published only in Melbourne in 1940.

Best Wishes,

Jamie

Jamie, I hadn’t noticed that, and thanks. I’ve added the information to the list of Rees’s books in that previous post. There’s also a lengthy gap between that book and his previous one, which came out in 1934. There’s probably an explanation, but at this late date, it would be awfully hard to find someone who’d know.

Jamie’s second email refers to the post I did on Ramble House Books as soon as I learned that Fender Tucker was reprinting a couple of mysteries by British author Rupert Penny:

Hi Steve,

Noticed your mention of Rupert Penny. Did you know about his pseudonym Martin Tanner? See Al’s Addenda Part 5 on CrimeFictionIV.com. Penny is also mentioned in Geoff Bradley’s CADS Supplement Private Passions Guilty Pleasures, where Martin Edwards’ Private Passion/Hidden Gem are the books by Rupert Penny. Martin Edwards says that Penny (Thornett), after he gave up writing crime fiction, became a leading figure in the British Iris Society, editing its yearbook.

Best Wishes,

Jamie

You can follow the link to find Jamie’s information on Penny as Martin Tanner, but to save you the click of the mouse, here it is below. I believe that the years of birth and death for Thornett are new also.

TANNER, MARTIN. Pseudonym of Ernest Basil Charles Thornett, 1909-1970. Other pseudonym: Rupert Penny, q.v.

Cut and Run. Eyre, 1941 (correcting publisher and date)

Perhaps it’s clear from the title and Jamie’s mention of it what Private Passions Guilty Pleasures consists of, but if you go here you will learn more, and if you are like me, you will learn enough to know that it’s a must have.

In short, however, in celebration of the 50th issue of Geoff Bradley’s printed zine called CADS, 87 crime writers, critics, fans and CADS contributors responded to the topic of what authors and what mysteries they have secretly (perhaps) enjoyed the most. Their comments were then compiled and published in booklet form separate from CADS #50, but mailed along with it.

I don’t know if Jamie intended for me to mention it or not, but he’s one of the contributors, along with Martin Edwards, Colin Dexter, Reginald Hill and Peter Lovesey, to name but a few.

CADS is short, by the way, for Crime and Detective Stories.

« Previous Page — Next Page »