March 2007

Monthly Archive

Fri 16 Mar 2007

THE SCARLET CLUE. Monogram, 1945. Sidney Toler, Mantan Moreland, Benson Fong, Virginia Brissac, Ben Carter, Janet Shaw, I. Stanford Jolley [uncredited]. Director: Phil Rosen.

Tommy Chan: You know Pop, I’ve got an idea about this case.

Charlie Chan: Yes, well?

Tommy Chan: Well, I had an idea, but it’s gone now.

Charlie Chan: Possibly could not stand solitary confinement.

My brother and I used to watch these Monogram entries in the Charlie Chan series on television every Friday night when we were kids, and we sure got a hoot out of them — even, I’m sure, the earlier ones with Warner Oland as well. We had to keep the sound down, since our parents were sleeping in the downstairs bedroom then, so we sat as close to the screen as we could, and enjoyed the heck out of staying up late, because it didn’t happen often.

The funny thing is, I don’t remember any of them, only some general impressions. The crimes, the oddly stiff Sidney Toler, the interchangeable actors who played the number two or number three sons, and we wondered why Birmingham Brown (Mantan Moreland) wasn’t in all of them.

A major clue in this one is a bloody footprint found at the murder that occurs in the opening scene. The plot has something to do some radar plans that foreign agents want to steal, but because the scientific laboratory is in the same building, most of the action centers around a radio station where a relatively bad soap opera production has their on-the-air studio. (When Charlie visits the lab and is shown a wind tunnel with temperature and wind effects, we know immediately that the this same wind tunnel is going to play a large part of what happens later on. We are correct.)

The detection is minimal. I was steered to the most obvious guilty suspect as being the killer, but I didn’t have my head screwed on too carefully, I’m afraid. There are spies, stooges, blackmailers, and people in funny masks, enough to keep your eye off the fact that, as one obvious question among others, how was the elevator with its deadly surprise constructed? It must have been quite a feat, especially with nobody noticing.

I mentioned Mantan Moreland, the black comedian who later on got a bad rap, or so I’m told, for playing such broad comic relief in movies like this one. Actually, I think that he and Tommy Chan have more screen time than does Mr. Chan himself, and never a serious part of the investigation are they ever. (One wonders why a great detective like Mr. Chan would put up with … but, oh well, never mind.)

Moreland and fellow comedian Ben Carter do a couple of great turns in an old vaudeville bit called the “infinite” routine, wherein both men carry on a conversation something like this, with neither one ever quite completing all of their sentences:

“Why if it isn’t …”

“Yes, and I haven’t seen you since …”

“No, it was longer than that. Last time I saw you, you were …”

“Well, I’ve lost weight! And you lived in …”

“No, I’ve moved to …”

“That’s a bad neighborhood. How can you live there?”

and so on, and so on …

Afterward, a thoroughly befuddled Tommy Chan asks, “Who was that?”

Birmingham’s answer: “He didn’t say.”

Well, my brother and I thought it was funny. We also woke our parents up and we were sent to bed.

Thu 15 Mar 2007

WILLIAM MAGNAY – The Hunt Ball Mystery.

Ward Lock, UK, hc, 1918. Brentano’s, US, hc, 1918. Other later printings exist, including Aldine Mystery Novels #22, UK, 1927. Etext at the Gutenberg Project.

Give me a novel opening with a fellow arriving for a social gathering at a country house, and I’m as happy as the proverbial clam.

The Hunt Ball Mystery begins in just this fashion, and right away we are in crisis mode. Hugh Gifford discovers he is without evening clothes due to a mistake made by the guard unloading luggage. Gifford and his friend Harry Kelson are going to a Hunt Ball to be held that evening at Wynford Place.

The station master arranges for Gifford’s traps to be transferred to a down train at the next stop, although Gifford won’t get them until about ten. However, this still leaves time for him to attend the ball.

The two men share a fly to the Golden Lion Hotel with a stranger who mentions he is also staying there and will be going to the ball. Gifford sniffily decides the man is not of their class, a conclusion based largely on the other’s looks and manner. The man is Clement Henshaw, brother of Gervase, whom Gifford knows by repute as a fellow legal eagle.

Gifford insists Kelson goes on to the ball ahead of him, and Kelson and Henshaw depart. While waiting for his missing luggage, Gifford decides to stroll over to Wynford Place to take a look at its exterior. He returns two hours later, obviously having had a shock. Even so, he dons his now retrieved evening clothes and tootles off to the jamboree, where he makes the acquaintance of Dick Morriston, owner of Wynford Place, and Dick’s sister Edith.

Not long before four next morning the hotel landlord pops in to ask if the Hunt Ball is over as Henshaw has not returned. After encouraging the landlord to lock the doors against his missing guest, Kelson pours himself a drink and suddenly notices blood on his shirt cuff.

Then the missing Henshaw is found dead in a locked room with the key on the inside and an 80 feet drop from its window. The general consensus is Henshaw committed suicide. Gervase Henshaw, the dead man’s brother, disagrees, and so does the doctor who gives evidence at the inquest.

At this point the mystery gallops off in full cry after the fox of whodunnit, how, and why. Revelations follow concerning what upset Gifford on his nocturnal walkabout, whence came the blood on Kelson’s cuff, the solution to the locked room matter, and so on.

My verdict: I have long been a fan of the Country House Mystery and so was disposed to like The Hunt Ball. Alas, this particular visit to a rural estate was not too successful. The locked room solution is pedestrian and most readers will guess it. I found the characters unsympathetic and the police presented as inept, not least in overlooking a couple of clues — including one of a particularly glaring nature. Then too the introduction of an important witness was without previous hints of this person’s existence.

It may be this novel was intended as a spoof of the Country House Mystery, but all in all, I found The Hunt Ball Mystery something of a disappointment.

From Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, a chronological listing of Sir William Magnay’s other mystery fiction:

MAGNAY, [Sir] WILLIAM, 2nd baronet (1855-1917)

* The Fall of a Star (n.) Macmillan 1897.

* The Heiress of the Season (n.) Smith, Elder 1899. Appleton, US, 1899.

* The Pride of Life (n.) Smith, Elder 1899.

* The Man-Trap (n.) Smith, Elder 1900.

* The Red Chancellor (n.) Ward 1901. Brentano’s, US, 1901.

* The Man of the Hour (n.) Ward 1902.

* Count Zarka (n.) Ward 1903.

* -Fauconberg (n.) Ward 1905.

* -A Prince of Lovers (n.) Ward 1905.

* The Duke’s Dilemma (n.) Long 1906.

* The Master Spirit (n.) Ward 1906. Little, US, 1906.

* -The Amazing Duke (n.) Unwin 1907.

* The Mystery of the Unicorn (n.) Ward 1907. Street & Smith, US, 1910.

* The Pitfall (n.) Ward 1908.

* The Red Stain (n.) Ward 1908.

* A Poached Peerage (n.) Ward 1909.

* The Powers of Mischief (n.) Ward 1909.

* The Long Hand (n.) Paul 1912.

* Paul Burdon (n.) Paul 1912.

* Rogues in Arcady (n.) Ward 1912.

* The Fruit of Indiscretion (n.) Paul 1913.

* The Players (n.) Hodder 1913.

* The Price of Delusion (n.) Paul 1914.

* The Black Lake (n.) Paul 1915.

* The Cloak of Darkness (n.) Ward 1915.

* The Hunt Ball Mystery (n.) Ward 1918.

* The Flamards Mystery (n.) Pemberton 1942.

* The Eleventh Hour (n.) Odhams n.d.

Wed 14 Mar 2007

From John Herrington, as a followup to a

previous blog entry describing the unsolved puzzle over who Golden Age mystery writer A. Fielding really was —

Hi Steve,

Here are my latest notes on Fielding/Feilding in case someone can add anything.

Further to my questioning of A. Fielding being the pen name of Lady Dorothy Feilding, I have a little more information — but also more questions.

Working on the belief that her American publisher was correct in saying the author’s real name was Dorothy Feilding and had lived in Sheffield Terrace, Kensington, I retraced my steps and found that the statement was correct.

Initially I checked the London telephone directories for the 1930s and — a Mrs A. Feilding was listed at 2 Sheffield Terrace from 1932 to 1936. A phone call to the Local Studies Library at Kensington, a check of the electoral roll for the period and there she was — Dorothy Feilding. No sign of Mr A. though. (Sadly, my previous enquiry had only seen the 1937/1938 rolls checked when she was no longer there).

The phone books showed that she had moved to Islington for 1937, but by 1939 she had ‘disappeared’ from the listing.

Unfortunately that is the sum of my search so far. A Dorothy Feilding (Mrs A.) was living in London circa 1932-1938 but so far no trace of her either side of that time. Also, there is no trace of Mr A. yet. Was she a widow, separated, was her husband away from home at the time? No idea. (Lady Dorothy’s husband was Charles Joseph, and anyway, his surname was Moore).

There was an Albert Feilding born in Yorkshire in 1869, but cannot find another male A. Feilding from then to end of century. Possible the husband was not born in England or Wales, I wonder?

There is also no trace of her in the probate registry up to the 1960s, but then she may died without making a will. I have yet to make a quarter by quarter search for her and her husband in the deaths registers.

Not a great deal to say, but I think this at least removes Lady Dorothy from the scene.

I have one other goodie which might be worth throwing out for comment.

As you may now, the major English novelist C. P. Snow’s first book was a murder mystery, Death under Sail.

Recently I was checking Author and Writers Who’s Who 1934 and came across the entry for a Kathryn Barber — who is in Crime Fiction IV for a couple of novels as Kay Lynn. But, to my surprise, her list of publications also include Death under Sail (in collaboration)!!

Did a quick Google, but could find no mention of anyone but C. P. Snow in connection with the book..

Wonder if anyone can throw any light on this?

From

Crime Fiction IV:

SNOW, C(harles) P(ercy) [Baron Snow] (1905-1980)

* Death Under Sail (n.) Heinemann 1932 [Ship]

* -Strangers and Brothers (n.) Faber 1940 [Lewis Eliot; England; 1929-30]

* The Sleep of Reason (n.) Macmillan 1968 [Lewis Eliot; England; 1963-4]

* A Coat of Varnish (n.) Macmillan 1979 [London]

LYNN, KAY

* Laughing Mountains (n.) Hutchinson 1934

* Dark Shadows (n.) Hutchinson 1935

Wed 14 Mar 2007

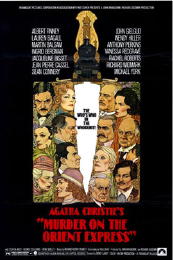

The following conversation between Peter Rozovsky and myself previously appeared as a series of comments after my

review of the 1974 movie version of

Murder on the Orient Express, which you should go back and read, or even re-read, before continuing on with what we had to say. Peter goes first:

This will not be an easy comment to make, since my one quibble with the movie involves a plot point, and I want to avoid giving vital information away to anyone who has not yet seen the movie. As Poirot did, I prefer the easier solution. So, first, for the simple matters.

I agree completely with your assessment of Albert Finney’s performance. He is almost demonic at times, almost scary, which is the last thing one expects of a Poirot. His performance was a most pleasant surprise.

Lauren Bacall’s performance was enjoyable, but I liked Ingrid Bergman’s better. And I had never realized until now not just how beautiful Vanessa Redgrave’s face was, but how wonderfully she could use it. I also enjoyed John Gielgud’s and Richard WIdmark’s performances as well as several of the others.

If the movie reflects the novel faithfully, I can see which aspect would have troubled censors. It’s a sobering question that such a matter could keep the story off the screen for so long.

Finally, the plot point: the resolution, as presented on screen had a ritualistic aspect that I found far-fetched. I can say no more until everyone in the world has seen the movie or read the novel. When that happens, we can discuss my objection openly.

Peter

Detectives Beyond Borders

“Because Murder Is More Fun Away From Home”

========================

Peter

Or should I call you “Artful Dodger.” Thanks for being so skillful in saying what has to be said about the movie without actually revealing what it is that can’t be talked about.

Why is it, I wonder, why so many otherwise intelligent people can’t resist giving the solutions away to detective story plots? Only this morning I read an op-ed column in the Hartford Courant which, to make another point, gave away for nothing the ending of Murder on the Orient Express.

And as for The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, the mystery that Christie is even more famous for, you can forget it. Even people who are trying to recommend the novel to others do so by saying, “You’ll never guess who did it. It was …” And every kind of variation on blab, blab, blab comes spouting forth.

In any case, however, I certainly agree with you about the way the crime itself was committed, as shown on the screen. It seemed to me to be borderline distasteful. But more than that, because of the sensationalistic nature of this aspect of the film, the point that (I think) was intended to be conveyed was lost.

One other thing. While I enjoyed Lauren Bacall’s performance more, in more ways than one, I would not have considered it worthy of an Oscar. Ingrid Bergman’s, yes, even if I quibbled about it.

– Steve

========================

I thought it was less distasteful that it was slightly ridiculous. I’ll have to go read the novel to see how Christie made the same point and if she did so any differently.

Regarding people who give away plots, they are selfish, stupid, or simply unable to distinguish between contemporary crime stories, in which who did it tends to be less important, and older ones, in which the mystery aspect is paramount. They add obtuseness and lack of taste to their selfishness or stupidity.

I realize now that one aspect of Ingrid Bergman’s performance may have especially endeared it to Oscar voters. She was a beautiful woman playing an unbeautiful character. It’s been noted that Oscar voters tend to reward that sort of thing.

— Peter

========================

I responded by describing what I cannot divulge here, but I mentioned Ingrid Bergman’s performance in a way that *might* disclose plot points that I shouldn’t, and Peter agreed with me about her. I also spoke in detail about what I saw behind the way the murder was committed. Peter replied that he hadn’t noticed or realized that, and that in retrospect the clues were fairly planted, a nice touch.

Now of course you may be wishing you had a rolling pin to throw at me, and if I were in your shoes, I think I might be wishing the same. To that end I have uploaded the continuation of our conversation here. Please note that the ending will be discussed in detail, and it is up to you to decide whether it is safe for you to go read it or not.

Tue 13 Mar 2007

By profession a dedicated newspaperman and sportswriter, Charles Einstein also dabbled in writing mystery and crime fiction. He died last week, and a more fitting and heartfelt tribute to him could not be found anywhere than this one by crime writer Wallace Stroby, who was also his editor at The Newark Star-Ledger for several years, not to mention a very close friend.

You should read the entire piece yourself, of course, and I hope you will, but to illustrate what kind of interesting family Mr. Einstein came from, here are couple of paragraphs I’ve taken the liberty of excerpting from it:

“His father was Harry Einstein, a radio, vaudeville and film comedian who billed himself as ‘Parkyakarkus’ and was a regular on Eddie Cantor’s NBC broadcast (he also became posthumously famous for suffering a fatal heart attack at a Friar’s Club roast in 1958, when tablemate Milton Berle’s cries of ‘Is there a doctor in the house?’ were misconstrued as shtick).

“Charlie had two half-brothers as well, from his father’s second marriage – Albert Einstein and Bob Einstein. Albert, of course, eventually became writer/director/comedian Albert Brooks, and Bob went on to cable fame as ‘Super Dave Osborn’ and is now a regular on HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

As a sportswriter, Charles Einstein was, among other honors, a lifetime member of the Baseball Writers Association of America. His works include four Fireside Books of Baseball, The New Baseball Reader, and (with Willie Mays) Born to Play Ball and My Life In and Out of Baseball.

As a mystery writer, his resume, while significant, is not nearly as extensive. Here’s a slightly expanded version of Mr. Einstein’s entry in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

EINSTEIN, CHARLES (1926-2007)

# The Bloody Spur (n.) Dell First Edition #5, pbo, 1953; reprinted as

While the City Sleeps (Dell D86, 1956)

# Wiretap! (n.) Dell First Edition #76, pbo, 1955

# -The Last Laugh (n.) Dell First Edition A121, pbo, 1956

# No Time at All (n.) Simon & Schuster, hc, 1957. Dell, pb, 1958.

# The Naked City (co) Dell First Editon A180, pbo, 1959. Stories based on TV scripts by Stirling Silliphant.

• “And a Merry Christmas to the Force on Patrol”

• “Lady Bug, Lady Bug…”

• Line of Duty

• Meridian

• Nickel Ride

• The Other Face of Goodness

• Susquehanna 7-8367

• The Violent Circle

# The Blackjack Hijack (n) Random House, 1976. Fawcett Crest, pb, no date.

I called his resume “significant,” and here are some details to back up that statement. First the movies, then the books the films were based on:

THE MOVIES:

The Bloody Spur was made into the RKO movie While the City Sleeps, 1956, directed by Fritz Lang. A top-notch film noir / social criticism film about the role of the media (newspapers vs. TV) while a serial killer is on the loose, it sounds as though it should be on DVD but for some reason, it does not seem to be. The movie stars Dana Andrews, George Sanders, Ida Lupino, Vincent Price, Rhonda Fleming, Howard Duff, Thomas Mitchell and Sally Forrest.

No Time at All was filmed as an episode on Playhouse 90 in 1958. [See the cover of the paperback edition.] Available on video, an online description calls it: “A sort-of Airport of its time, this production tells of a stricken airliner that must make its way through the heaviest air traffic in the world without lights and radio. Among the cast members are William Lundigan, Jane Greer, Betsy Palmer, Keenan Wynn, Charles Bronson, Jack Haley, Buster Keaton, Chico Marx and Sylvia Sidney.”

The Blackjack Hijack was the basis for the TV movie Nowhere to Run, 1978, starring David Janssen, Stefanie Powers and Allen Garfield. Synopsis of the movie, paraphrased from IMDB: “To get out of his marriage with Marian, world-weary Harry plans to fake his death and assume a new identity. His wife gets suspicious and hires a private eye, but when Harry discovers this, he hires the PI to work for him instead.”

THE BOOKS:

The Bloody Spur. “‘Help me for gods sake.’ Later the doctors would use these words to decipher the riddle of a perverted killer. Right now, the lipstick scrawl signaled the start of New York’s greatest manhunt.

“And in the city room of the fabulous Kyne News empire, four big-time newsmen went into action. All four knew that an exclusive beat on the killings would mean the top job at Kyne – and they were all hungry for the job. Hungry enough to buck the police, sell out their mistresses, and commit blackmail. Four decent men – corrupted by the blood spur of ambition.”

Wiretap! “Men with a golden ear. In the city of Aimerly they were the cops, the city prosecutor, the rackets boss. Their electronic spies recorded the intimacies of boudoir and office – intimacies later priced, and paid for.in cash or blood. Then a judge who knew where all the bodies were buried got himself murdered. And Sam Murray, State Crime Commission, walked into a maze of tapped phones, secret cameras, hidden mikes. Various people tried to sidetrack Sam, with the help of two ladies who were specialists at their work. But when Sam kept pushing, they gave him a choice – rot in jail, or send the last honest man in town to do it for him.”

The Last Laugh. “Sam Prior was an off-stage straight man for Carl Anda and Jay-Jay Bailey, whom readers should be careful not to confuse with real-life entertainers, living or dead. And he was a straight man for his wife Rachel, whom he should have left where he found her, singing with her hips at a Borscht Circuit hotel. He tells his own story in his own words, warm and wry and funny. He’s a nice guy, and in the dog-eat-dog world of professional comics, they eat nice guys for breakfast.”

The Blackjack Hijack. About the author, taken from the dust jacket flap: “In a career that has included years as a wire-service newsman and feature writer in New York and Chicago, and as columnist and editor for two San Francisco dailies, Charles Einstein also has authored several hundred other works — books, screenplays, short stories, magazine articles. The Blackjack Hijack is his ninth novel and, he notes, the first in which he appears as a character in his own book, playing the part of an expert on the game of blackjack. Here art imitates life: in 1968 author Einstein published another book – now in its fourth printing and hailed by ranking computer programmers and other mathematicians as the best and simplest in the field — called How to Win at Blackjack. Both born in New England in the late 1920’s, the author and his wife first met as undergraduates at the University of Chicago, and with their four children, now all in their twenties, migrated subsequently from New York to Arizona to California.”

Sun 11 Mar 2007

ANN WALDRON – The Princeton Imposter

Berkley, paperback original. First printing, January 2007

This is the fifth mystery novel from Ann Waldron’s pen, all of them in her McLeod Dulaney series. According to her website, she’s also the author of a number of well-regarded biographies and a number of children’s books, both fiction and non.

Like her fictional character – who’s female, by the way, which I’d better add in case you’re seeing her name for the first time and you’re not sure – Ann Waldron has been a journalist and writer her entire working career. For the record, here’s the list of all five of her mysteries, each of them taking place in and around Princeton University:

The Princeton Murders. Berkley, pbo; January 2003.

Death of a Princeton President. Berkley, pbo; February 2004.

Unholy Death in Princeton. Berkley, pbo; March 2005.

A Rare Murder in Princeton. Berkley, pbo; April 2006.

The Princeton Imposter. Berkley, pbo; January 2007.

I imagine you see the pattern here as well as I do. Whenever McLeod Dulaney is on campus, that’s the semester you should be heading abroad or taking a sabbatical. McLeod herself is not a full-time faculty member; she’s an award-winning journalist and a visiting professor from Florida who teaches one course in journalism a year at Princeton University. Not so coincidentally, that is precisely where the author herself began working more than 30 years ago.

Which is why the love of the school and campus – the students, the staff and the professors, the legend and the lore – is as much of a key ingredient of the story as it is. The “imposter” in the title is Greg Pierre, one of McLeod’s better students, an older student who managed to gain admission to the university under an assumed name and falsified credentials. It seems that he’d previously been arrested in Wyoming – on false charges he says – and in order to come to New Jersey, he had to break parole.

And soon after his arrest the fellow who turned him in is found murdered, a grad student in the chemistry department who (as it turns out) was highly unliked for a number of reasons, which makes for a long list of suspects. But when McLeod’s good friend in the police department, Lt. Nick Perry, seems to settle in on Pierre as the most likely of them – no surprise there – she thinks otherwise, and she sets out to prove it.

Waldron writes in short, crisp, no-nonsense sentences, and McLeod Dulaney, in a number of ways her fictional alter ego, perhaps, conducts her investigation in very much the same style. Investigative journalists, by the nature of their profession, soon acquire the knack of asking questions in a way that people answering them sometimes reveal more than they intended, or if not, they quickly find another line of work. McLeod doesn’t need to worry on that account.

On the other hand, while she does a whole lot of detecting, she does not do a whole lot of deducting. (One does not necessarily imply the other.) First she decides that this student is the guilty party, then that professor, and as a result, she always seems to be one step behind – she doesn’t ever seem to catch up. Which of course leads to the ending. In my book, it comes as a letdown, leaving the reader (me) feel caught standing on the wrong foot at the wrong time, or should that be the right time? It also feels cluttered — more for dramatic effect, I thought, than for any other reason.

Overall, then? Here’s a book that’s well worth reading for anyone who’s fond of mysteries which either take place in academic locales or rank well above average in the writing department, or both. You can take my other caveat for whatever it might be worth.

— January 2007

Sat 10 Mar 2007

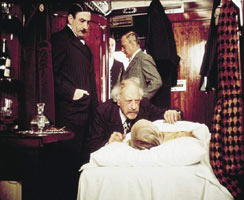

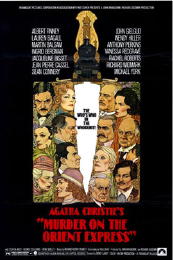

MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS. Paramount, 1974. Albert Finney, Lauren Bacall, Martin Balsam, Ingrid Bergman, Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Anthony Perkins, Denis Quilley, Vanessa Redgrave, Rachel Roberts, Richard Widmark, Michael York, George Coulouris. Directed by Sidney Lumet.

They don’t make movies with all-star casts like this anymore, and maybe for a couple of good reasons. First of all, I don’t think you can convince me that in this modern, contemporary era of movie-making there are enough stars with the on-screen magnitude to match the ones you see above to make a film like this today.

And secondly — and here’s a point in favor of the small-scale modern day casting — having too many stars can sometimes detract from the story and divert the audience’s attention away from it.

Your eye sees the star, in other words, and you don’t see the character. The actors play roles rather than disappearing into parts. It probably can’t be helped in extravaganzas like this, but — and this is a rather subtle “but” — in thinking it over afterward, in terms of this grand, elaborate production of one of Agatha Christie’s masterpieces of deductive detective fiction, it may have even helped.

I’m sorry if I’m being cryptic here, but if you’ve seen the movie, it’s possible that you very well know what I mean.

Before going on, and perhaps I shouldn’t admit it, but last night was the first time I’ve seen the film. I don’t know how I missed it when it first came out, or if I did, I’ve forgotten it completely, and I hardly believe I could have done that.

So in what follows, you’re getting my opinion as it’s just been formed, with a “mature” eye, and not by the eye of a 30-something. (Notice that I put “mature” in quotes, keeping in mind that being old enough to collect Social Security does not necessarily imply mature.)

Albert Finney as Poirot. Other than the later BBC productions with David Suchet, and I regret to say that I have seen only one of them, I think too many actors play Poirot as a comic character, what with his large assortment of eccentric mannerisms and sometimes faulty English.

In the opening minutes of Orient Express, I could feel myself cringing at the anticipation of yet another performance played for laughs, but when Poirot gets down the business of solving the murder of a notorious crime figure traveling incognito on the train heading from Istanbul to England, he is exactly that. Down to business.

The final scene, confronting the group of passengers who are the only suspects on the snowbound Express, takes at least 20 minutes of intense revelation, going over the clues and the deductions the Belgian detective made from them.

I should have timed how long the scene actually takes. I know that I’ve read somewhere that filming the scene, in the restricted confines of the dining car, took several days. I can believe it.

Luckily the flashback scenes, with the crime being reconstructed, piece by piece, break up the sequence of talking heads in a rhythm that slowly builds and builds upon itself.

Even so, the lack of action that this approach entails means that there’s hardly action enough to suit modern day audiences, or am I only being cynical again?

Finney is probably the only actor to play a detective concerned with clues and not the third-degree in back rooms to have been nominated for an Oscar, but on second thought, without going to check on it, there’s a finite chance that I’m wrong about that.

But as for his performance, as regarded by others, according to IMDB: “An 84-year-old Agatha Christie attended the movie premiere in November of 1974. It was the only film adaptation in her lifetime that she was completely satisfied with. In particular, she felt that Albert Finney’s performance came closest to her idea of Poirot. She died fourteen months later, on January 12, 1976.”

If she was pleased, then how I dare say anything otherwise? I can’t, and I don’t. As for the rest of the cast, while I enjoyed Lauren Bacall’s role as the the outspoken (and never stopping) American tourist more, it was Ingrid Bergman who actually won an Oscar, for her much briefer part as a semi-demented Swedish missionary lady. A good performance, even a very good one, but I have a feeling it may have been a slow year for the Academy.

Should I say something about the plot, more than I have so far? Perhaps not, but this is a tour de force of some magnitude, based as it was on the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby. The book was first published in England in 1934, and as Murder in the Calais Coach in the US later the same year.

Before the movie was shown on Turner Classic Movies, which is where I taped it from, the host, Robert Osbourne, pointed out that it took 40 years before the movie could pass the Movie Code. If you know the story, you will know why, and once again, that is all I am able to say about that.

In terms of the detective work — well, let me tell you a story. Back when I was young, and maybe even younger than that, I decided that the next Agatha Christie novel I read, by golly I was going to take detailed notes and actually solve the murder myself. Well I did, and I didn’t.

I was so upset at how the crime was committed and who did it that I literally threw the book across the room. Carefully, of course.

The movie was extremely successful. Albert Finney was asked, but he turned down the opportunity to play Poirot again. Peter Ustinov, chosen in his place, played the part in Death on the Nile (1978), Evil Under the Sun (1982), and Appointment with Death (1988).

He also appeared in three made-for-TV films: Thirteen at Dinner (1985), Dead Man’s Folly (1986), and Murder in Three Acts (1986). From what I remember — I haven’t seen any of these films in a while — I mostly regretted Ustinov in the role. Albert Finney, I think I could have gotten used to, now that I’ve had some time to think it over, and even more so as time goes on.

[UPDATE] 03-11-07. Looking back on my comments above, I regret not saying more about the opening terminal scene with the passengers boarding the train in the Istanbul station. Beautifully photographed, highly choreographed, and true to the period, it is nearly worth the price of admission in itself.

Before I say anything more about it, though, I’m going to have to go back and watch it again. It was far too “visual” the first time, but for me, opening scenes often are. I find myself trying to make sure I’m not missing anything of the story while, at the same time, I’m struggling to take in everything there is to see. Delightful!

[A little bit later.] It was too hard to resist. I’ve just ordered the DVD from Amazon, the version with director Sidney Lumet’s commentary on “The Making of the Movie,” and who should know more how the movie was made than he?

Fri 9 Mar 2007

There’s good news tonight!

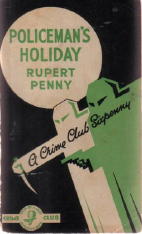

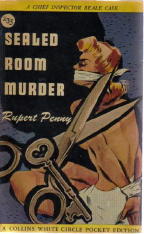

Taken from publisher Fender Tucker’s latest email newsletter, Ramble House Rambler #52, along with the other upcoming mystery fiction he’s promising to go to press with soon, I was doubly delighted this evening to see the following:

Two books by Wade Wright, author of the Paul Cameron series.

ECHO OF FEAR and

DEATH AT NOSTALGIA STREET. The author, who lives in South Africa, is working with Ramble House to bring back all of his mystery novels.

Two novels from Rupert Penny, whose mysteries are filled with puzzles, time-charts, maps, railway schedules, etc. Thanks to friends in high places — Petaluma CA and Rockville MD — I was able to obtain copies of two hard-to-find titles: POLICEMAN’S HOLIDAY and POLICEMAN’S EVIDENCE. I’m working on them now.

Delighted first of all because, as you may recall, John “Wade” Wright was interviewed here not too long ago. These will be the first US editions of any of his novels. It’s been a long wait, but it shouldn’t be too much longer. And if more are coming, as Fender seems to suggest, then all the better.

As for Rupert Penny, he’s an author that I’ve always assumed to be a huge insiders’ secret. He wrote eight extremely scarce works of solid detective fiction between 1936 and 1941, and I’m lucky enough to have seven of them. I bought them back when they were still hard to find, but when you did, they were still relatively inexpensive. I don’t believe that I paid more than ten dollars for any one of them, but 30 to 35 years ago, ten dollars was a huge pile of change.

Only two of the books are available on ABE at the moment. There is one copy of Sealed Room Murder, a Canadian paperback in VG condition for $145, and six copies of Policeman’s Holiday, all in paperback also, with asking prices ranging from $65 (a very worn reading copy) to $165. I haven’t checked the other online listing sites, but right now, not a single hardcover first edition is being offered on ABE.

The Ramble House editions will be the first time that any of Rupert Penny’s will be available in the US. To whet your appetite, here’s a synopsis of Sealed-Room Murder. If your reading tastes are anything like mine, this will be hard to resist. (Unfortunately it’s not one of the book currently on Fender’s schedule, but I think it will get your mind thinking in the right direction.)

RUPERT PENNY excels all his previous form with this highly successful murder mystery. Unlike most “sealed-room ” stories, the problem is perfectly clear-cut and extremely simple in its elements. Where other mysteries try to baffle the reader by their complexity, this one will baffle by its simplicity. The story of Harriet Steele and the family that was forced upon her, is good reading even when considered as a straight novel, the situation is very real, very familiar and always lively and amusing in spite of the undertone of grimness. The thoroughly ingenious and exciting crime is put before the reader with scrupulous fairness so that he has every possible chance of leaping to the solution that will prove completely satisfying.

From Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, to whet your taste buds even more, assuming perhaps that the first two sell well, and that Fender can locate copies of the rest of them to reprint:

PENNY, RUPERT; pseudonym of Ernest Basil Charles Thornett. Series Character in all titles: Insp. (Chief Insp.) Edward (Ted) Beale.

* The Talkative Policeman (n.) Collins 1936

* Policeman in Armour (n.) Collins 1937

* Policeman’s Holiday (n.) Collins 1937

* The Lucky Policeman (n.) Collins 1938

* Policeman’s Evidence (n.) Collins 1938

* She Had to Have Gas (n.) Collins 1939

* Sweet Poison (n.) Collins 1940

* Sealed-Room Murder (n.) Collins 1941

Fri 9 Mar 2007

As part of the review that Mary Reed just did of Mary Roberts Rinehart’s When a Man Marries, it was noted that a free online edition exists. Here’s a complete list of all of MRR’s books which can be found on the Project Gutenberg website.

* = title in Crime Fiction IV, by Allan J. Hubin.

** = title listed as having marginal crime content in CFIV.

Project Gutenberg Titles by

Mary Roberts Rinehart

Thu 8 Mar 2007

Following my recent

review of Mary Roberts Rinehart’s

The Yellow Room, mystery writer Mary Reed posted this on the Yahoo

Golden Age of Detection list as a follow-up companion piece. The crime element in

When a Man Marries is so slight that the book is not currently included in Allen J. Hubin’s

Crime Fiction IV, but as Mary will suggest, perhaps it should be.

When a Man Marries is available online in etext form at the Gutenberg Project. Mary also points out that some additional biographical information on Mrs. Rinehart can be found online, including this website as a prime example.

Mary Reed has her own website, shared with her co-author Eric Mayer; you are cordially invited to stop by. Mary and Eric also did a Pro-File interview for the original Mystery*File website before it went on its current long hiatus.

MARY ROBERTS RINEHART – When a Man Marries (Bobbs-Merrill; hc, 1909. Hardcover reprint: Grossett & Dunlap, no date. Wildside Press, trade ppbk, 2004)

Being excessively fond of locked room mysteries, imagine my delight once I began reading When A Man Marries to find it based on a twist on same. Set in a house full of Bright Young Things (sent up mercilessly by the author, Mary Roberts Rinehart, whose The Circular Staircase is occasionally mentioned within these walls) the plot unspools as several BYT’s suddenly find themselves sequestered in a large house under quarantine because the butler has just been stricken with smallpox.

Meantime, the protagonist has agreed to pretend to be the wife of the house owner. This came about because the BYTs are attending a dinner party at the house, during which their host learns his dragon of an aunt — who holds the purse strings — is coming for an unexpected visit. This rich aunt has not been told he is now divorced because then the flow of money would end (fortunately she hasn’t met the now ex-wife). Complications of course ensue including the rest of the servants decamping before the Board of Health quarantines the house, leaving in such haste they do not even bother to tell the master why they are leaving, the ungrateful things.

There’s a policeman imprisoned in the furnace room, and no sooner is the house and its inhabitants securely locked down for the duration when valuable items such as jewelry start going missing … meanwhile, the ex-wife having arrived just before quarantine was declared is now concealed from the aunt’s eyes in the kitchen below stairs, Rich Aunt is also locked in the house with the entire bunch, and one of other Bright Young (Male) Things foolishly wagers a large sum the entire crew will get out of quarantine within 24 hours — quite illegally of course and talk about chronic lack of social conscience — plus there are newspapers reporters and photographers camping around the house as well as on the roof of the house next door to keep an interested public fully informed.

It struck me as I read that it would have made a wonderful screwball comedy/mystery with Cary Grant playing the fellow imprisoned engineer from South America, who is most emphatically *not* a BYT. How could you not laugh out loud at the whole frothy affair?

And I did, Oscar, I did.

[UPDATE] 03-09-07. When I asked Mary to say some more about the criminous content of When a Man Marries, this was her reply:

I would describe this novel as a romantic comedy with mystery overtones, since the question of who pinched the jewelry plays a less prominent part than in other MRR works, and comes to prominence towards the end of the book. But little hints are planted here and there as I realised when I got to the solution and thought it over a bit.

Thinking that Al Hubin might like to know this, I sent Mary’s comments on to him. Here’s what his response was, which was pretty much what I suspected it would be: