July 2008

Monthly Archive

Sun 20 Jul 2008

TERROR STREET. Lippert Films (US) / Hammer Films (UK), 1953. Known as 36 Hours in the UK. Dan Duryea, Elsy Albiin, Ann Gudrun (Gudrun Ure), Eric Pohlmann, John Chandos, Kenneth Griffith. Story & screenplay: Steve Fisher. Director: Montgomery Tully.

This is one of several (if not many) joint British-American productions in which a single star was imported from the US (Dan Duryea, of course, in this case) to make a movie, often a crime film, on the cheap in England, with the rest of cast consisting of only British and European actors and actresses.

Two box sets of these Hammer Film Noirs, as they’re called, have been issued so far. On the basis of Terror Street, and the only one in either set that I’ve seen, I’d say that the emphasis is on the cheap. I can’t say in what way, exactly. Maybe it was only poorly done, leaving me with little more to say. (But of course I will.)

Let me tell you about the story first. Dan Duryea plays an American flier names Rogers who marries a Norwegian girl (played by Elsy Albiin) he meets in England after the war, and they settle down there. When he’s called back to the States for some sort of training program, they have their first fight. Three months having turned into a year without hearing from her, he goes AWOL and heads back to England to see her and to learn why she’s cut off all contact with him

And guess what. She opens the door to her apartment to find him waiting there, he’s clunked on the head from behind, and he wakes up to find her shot to death beside him, his gun (and the murder weapon) in his hand.

Not waiting for the police to arrive for them to not believe his story, he heads out on the lam – and straight into the arms of Jenny Miller (Ann Gudrun) who works in a charity kitchen, which may help to explain why she takes him on as a charity case of her own.

This is not a detective story – we the viewers have already seen the killer do the deed, although of course we do not know why – nor, believe it or not, is it much of a suspense yarn, even though that’s the gimmick that’s meant to keep the story moving: Rogers has only 36 hours before his superiors learn that he’s gone, having smuggled himself into England without their knowledge or permission.

In those 36 hours, his quest is not only to find the killer and clear himself, but to discover why the long-distance romance with his wife broke up so badly. (Not realizing in the meantime that Jenny is becoming more and more important to him, and vice versa, only I think she realizes it first.) Various sleazy types try to stop them.

A true noirish situation, right? It was concocted by a writer who started his career writing for the pulp magazines, but this time, nothing that happens seems to ring true, and Duryea appears almost too tired and out of sync to pull off the role he’s to play here, that of both hero and victim. (In his early days of film-making, as you probably need not be told, Duryea was usually a villain.)

It is hard to say otherwise what goes wrong. The sets are cheap but for the most part, not that cheap, and there is plenty of exterior shooting that provides a glimpse of the non-touristy areas of London in the early 1950s.

Other than Duryea, the actors are rather stolid folk, with only Ann Gudrun, who was born in Scotland, showing much spark. She was only 5 foot 3, I’m told, but she plays her role with a restrained combination of wistfulness and strength. (In this regard, I wish I had another photo to show you, one without the tears, but so be it.)

Elsy Albriin is pretty without being beautiful, and if she’d been given a longer role, maybe some of the stiffness she shows early on would have worn away. (She did not have a very long career in either TV or the movies, especially in English-speaking roles.)

One last generalization, then, and I think it applies here as well. Whenever I watch a movie and all I see are actors standing on a soundstage, that’s when I know when neither the story nor the players has any kind of hold on me. No mesmerizing movie-time spells this time. While in no sense did I find it disastrously bad, Terror Street was largely a disappointment for me.

Sat 19 Jul 2008

ANTHONY GILBERT – The Black Stage.

Penguin, UK, paperback reprint, 1955. Hardcover first edition: Collins Crime Club, 1945. US edition: Smith & Durrell, hc, 1946. Also published as: Murder Cheats the Bride, Bantam #138, pb, 1948.

Between 1936 and 1974 there were, by my count, 50 recorded adventures of a slightly seedy, badly dressed and deliberately vulgar barrister detective named Arthur Crook, of which total this is one. The author, Anthony Gilbert, is described thusly on the back cover of the 1955 British paperback I happen to have:

“Little is known about the author except that his books are among the most popular stories written today…”

Of course we know better now, but it’s remarkable that the secret was kept a secret for so long. Anthony Gilbert was in real life a lady named Lucy Beatrice Malleson (1899-1973), and she has a whole string of other novels to her credit, not all criminous, both under this pen name and two or three others.

The earliest of the Crook stories were never published in the US, but after some point in the early 1940s, all of them seem to have been. Why was he called Crook? What a delightful deceit!

I’ve not read too many of them, and none recently, but I think The Black Stage fits the general overall pattern. Gilbert allows the events leading the inevitable murder to build up gradually, letting the characters (sans Crook) have full rein over their actions and letting the reader in on all of their possible motives, until at last the deed is done. In The Black Stage, that’s on page 74. (The lights had gone out immediately before, and when they are restored someone is standing with a gun in her hand over a body on the floor.) Crook is not met until page 94 (out of 219 in all), having been hired to represent the interests of Anne Vereker, the young woman being held for trial.

Which means, to Crook, finding the true guilty party. Perhaps it’s true in other books in the series, but there’s no courtroom theatrics in this book, only – toward the end – a reconstruction of the crime, designed solely to confuse the real killer into identifying him or herself.

Somewhat earlier, on page 148, Crook confides to his assistant that he knows who the killer is. If this had been an Ellery Queen novel, it would have been a terrific spot to have placed a “Challenge to the Reader.” Which I would have failed, which I almost always do, and in this case, shame on me.

You might be wondering if the 74 pages of preliminary action were at all boring. No, absolutely not. Not at all.

Each of the characters in the drama is wonderfully drawn, and with the widow about to marry a man who is so obviously only looking out for himself (and the woman’s diamonds), and not the others living at Four Acres who would be her heirs or who depend so greatly on Tessa Goodier – stop and take a breath, Steve – it is clear almost from the beginning who the victim will be.

The anticipation only grows and grows, in other words. The ensuing events and the subsequent investigation of the crime is, believe it or not, marginally less interesting – the actions and behavior of the participants less well described. (The author was trying, I believe, to make a relatively simply crime more complex and complicated than it needed to be, but if the middle events were not part of the story, then of course the book would have been, from anyone’s point of view, something less in length than a novel.)

But I love maps in crime novels (and there is one) and re-creations of crimes (of which I have already mentioned there is one also), so all is not lost, and in fact, much is regained.

One is only left to wonder in the end, then, whether the RAF officer Anne Vereker met after the war on the train she’s taking back to her home in the English countryside will manage to find her again. Could it be that now that the war is over, that class status will no longer make a difference to them?

(Not that she may even remember him, but it was he, in the only other part of the story where he comes in again, who recommended Arthur Crook to her cousin to act in her defense. That should count for something, shouldn’t it?)

Sat 19 Jul 2008

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

PETER ROBINSON – Piece of My Heart. William Morrow, hardcover, May 2006. Paperback edition: Harper, April 2007.

Robinson’s latest DCI Banks mystery skillfully alternates between a 1969 investigation into the murder of a young woman at a rock concert by DI Stanley Chadwick and the present-day investigation by Banks into the murder of a journalist who was working on a project involving a band, the Mad Hatters, connected to the earlier investigation.

Banks has moved back into his restored cottage which is now outfitted with high-end audio and video equipment from his late brother’s apartment, is adjusting to a new, ambitious boss, is still friendly with but no longer dating DI Annie Cabot, and displays his usual mix of thorough professionalism and stubborn independence that has always marked his investigative style.

And once again brings things to a successful conclusion. Another entertaining entry in a long-running, well-developed series.

MARGARET COEL – Eye of the Wolf. Berkley: hardcover, September 2005; paperback, September 2006.

I don’t find myself compulsively keeping up with this series, but the Indian reservation setting continues to interest me, even though I find the series suffers from the too predictable relationship of lawyer Vicky Holden and Jesuit priest, Father O’Malley.

Vicky is one of those bruised women who populate the current mystery scene, with a painful personal life that is less interesting than the case or cases that engage their professional attention.

I suppose this is intended to give them some of the density of the mainstream novel, but the convention is vastly overused and I think it’s time to give it a rest.

Fri 18 Jul 2008

In case you’ve been wondering, I haven’t had much time in recent weeks to work on the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, and I’ll have to see if I can’t do something about it. (Al supplies the basic data; I add the short biographies, images and links.) This grouping of newest entries is based on books in my own collection, and will be appearing soon in Part 29 of the Addenda.

ANTHONY, EVELYN. Pseudonym of Evelyn Bridget Patricia Ward-Thomas, 1928- . Born in London, England; married Michael Ward-Thomas, 1955. Author of many historical romances early in her career before turning to romantic suspense. Some 25 books falling into the latter category are included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV.

The Doll’s House. Bantam, UK, hc, 1992; Harper, US, hc, 1992. Add setting: England. [An agent pensioned off at the end of the Cold War sets up a syndicate of ruthless professionals up for hire.]

KENNEY, CHARLES (C.) 1950- . Began his writing career as a reporter for the Boston Globe; it was not until nearly 20 years later that he published his first crime thriller. Besides the two titles listed below, both included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, Kenney has also written The Last Man (Ballantine, 2001).

_Code of Vengeance. Ballantine, pb, 1997. See Hammurabi’s Code.

Hammurabi’s Code. Simon & Schuster, hc, 1995. Add: Reprinted as Code of Vengeance (Ballantine, 1997). Setting: Boston, MA. [When a liberal Boston councilman is murdered, investigative reporter Frank Cronin begins to learn the truth about him.]

The Son of John Devlin. Ballantine, hc, 1999. Setting: Boston, MA. A Harvard University graduate goes undercover to investigate corruption in the Boston Police Department, hoping to clear his father’s name and restore his reputation.]

LEE, RACHEL. Pseudonym of Susan Civil-Brown & Christian Brown. Under this pen name, the author of several romantic suspense novels included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, as well as others published after 2000. Add the title below:

Thunder Mountain. Silhouette, US, pb, 1994. [Silhouette Shadows #37.] Setting: Wyoming. [Mercy Kendrick is trapped on Thunder Mountain with a Native American hermit she can’t trust and men trying to track her down and kill her.]

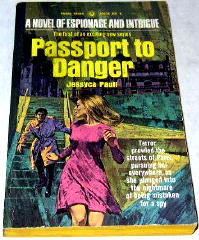

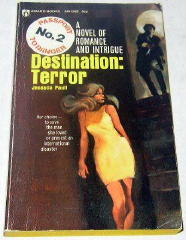

PAULL, JESSYCA. Joint pseudonym of Julia Perceval & Rosaylmer Burger. Under this pen name, the authors of three books in a spy thriller series called “Passport to Danger.” Series characters in each: British agent Mike Thompson and his American fiancée, Tracy Larrimore.

Destination: Terror. Award, pb, 1968. [#2.] Add settings: New York City, Luxembourg. [Tracy is kidnapped and shipped to the headquarters of the sadistic leader of an espionage ring.]

Passport to Danger. Award, pb, 1968. [#1.] Setting: Paris. [Danger follows Tracy everywhere in Paris, where she is mistaken for a spy.]

Rendezvous with Death. Award, pb, 1969. [#3.] Setting: Caribbean. “Two rival powers on a Caribbean island use a honeymoon couple as bait in a cat and mouse game of international espionage.”

Fri 18 Jul 2008

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

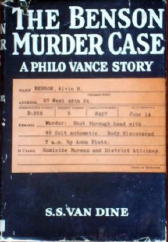

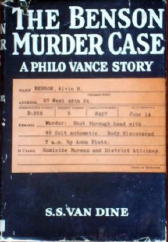

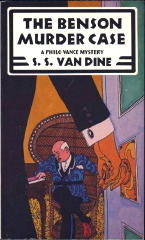

S. S. VAN DINE – The Benson Murder Case. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926. Hardcover reprints include: A. L. Burt, no date (shown); Gregg Press, 1980. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #333, 1945 (shown); Fawcett Gold Medal T2006, no date (ca.1968); Scribner’s, 1983 (shown).

Narrator ‘Van’ Van Dine originally met Philo Vance at college and is now not only a close friend but also his full-time legal and financial advisor. He is thus on the spot to record cases in which Vance becomes involved.

Vance is rich and cultured, possessing many beautiful and rare examples of art and artefacts from various eras and continents. He easily out-Wimseys Wimsey, what with addressing people as ‘Old dear’ and constantly talkin’ ragin’ nonsense, often dropping French or German into conversations with an occasional bit of Latin for variety, not to mention quoting luminaries such as Milton, Longfellow, Cervantes, and Rousseau as well as Spinoza and Descartes. But it’s all a front, of course.

John Markham, DA for NY County, arrives at Vance’s flat while Van and Vance are discussing business and announces wealthy broker Alvin Benson has been murdered. Alvin’s brother Major Anthony Benson has asked Markham to take charge, and Markham had promised Vance he would take him along on his next important investigation. It seems the authorities were casual about protocol as well as crime scenes, because not only do both Vance and Van tag along but they are also present at several interrogations.

At one point Vance produces a list of suspects based upon reasoning from available information and physical evidence. The only snag is they are innocent. It is a demonstration of his conviction that “The truth can be learned only by an analysis of the psychological factors of a crime and an application of them to the individual”.

Who then is the culprit? The actress Muriel St Clair, in whom the dead man had taken more than a passing interest? Her fiance Captain Philip Leacock, he of the hasty temper and jealous disposition? Major Benson, given the brothers did not get along? What about Mrs Anna Platz, Alvin’s housekeeper, who seems to be hiding something, or the precious and impecunious Leander Pfyfe, a close friend of the deceased?

My verdict: Some will find Vance’s insistence on keeping the identity of the murderer secret irritating but given he had it sussed out within an hour or two of visiting the crime scene, one can see why.

To be fair, he all but takes Markham’s hand and leads him to the culprit. There are clues aplenty, and to my delight the author provided those much-loved and now sadly missed tidbits — a room plan, a character list, and footnotes from Van.

Although readers may find Vance’s lit’r’y meanderin’s a bit tedious, his explanation of his psychological reasonings are interesting and convincing, although I am still not certain if the author was sending it up or using it as a genuine plot device. All in all, however, a good read with plenty of red herrings to confuse the issue.

Etext:

http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200341h.html

[EDITORIAL COMMENT.] Mary sent me this review back in September of ’07, along with a backlog of others. (Sorry, Mary!) I’ll get more of them online here soon, but after posting Bill Loeser’s recent comments about the same book, I thought I ought to pull this one out of the queue and give it some priority, the idea being that two independent views of a book are better than one, and certainly far better than none. (Where else has The Benson Murder Case been reviewed in the last 10 or 20 years?)

That’s a rhetorical question. You needn’t answer it.

Thu 17 Jul 2008

THE CURMUDGEON IN THE CORNER

by William R. Loeser

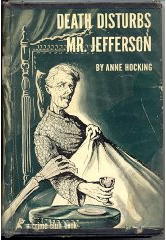

Based on an overall favorable review in Barzun & Taylor’s A Catalogue of Crime, I read Anne Hocking’s Death Disturbs Mr. Jefferson (1950). Solicitor Jefferson is found dead in bed, and it soon becomes apparent that someone had put a ringer in his bottle of sleeping pills.

At first, Jefferson seems to be an estimable character – he had no use for people and lives only for his glass collection – but it is discovered that he has been supporting his hobby/habit by blackmail on the basis of documents entrusted to him professionally.

At this point the reader is all on the side of the murderer. In a good touch, Ms. Hocking has overcome our misplaced running with the hare by making the culprit one of the blackmailees.

Most of the detection is ordinary policework and elimination of suspects because they aren’t “capable” of the crime. There is little action – even the killer is collared offstage.

Not bad, not good.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 2, Mar-Apr 1979 (slightly revised).

BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

ANN HOCKING – Death Disturbs Mr. Jefferson. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1950. Geoffrey Bles, UK, hardcover, 1951.

CHIEF INSPECTOR WILLIAM AUSTEN. Author: Anne Hocking, pseudonym of Mona Messer Hocking, (1890-1966).

Ill Deeds Done (n.) Bles 1938 [England]

The Little Victims Play (n.) Bles 1938 [England]

Old Mrs. Fitzgerald (n.) Bles 1939 [England] US title: Deadly Is the Evil Tongue.

So Many Doors (n.) Bles 1939 [Cyprus]

The Wicked Flee (n.) Bles 1940 [England]

Miss Milverton (n.) Bles 1941 [England] US title: Poison Is a Bitter Brew

Night’s Candles (n.) Bles 1941 [Cyprus]

One Shall Be Taken (n.) Bles 1942 [England]

Nile Green (n.) Bles 1943 [Cairo] US title: Death Leaves a Shining Mark.

Six Green Bottles (n.) Bles 1943 [England]

The Vultures Gather (n.) Bles 1945 [England]

Death at the Wedding (n.) Bles 1946 [England]

Prussian Blue (n.) Bles 1947 [England] US title: The Finishing Touch.

At “The Cedars” (n.) Bles 1949 [England]

Death Disturbs Mr. Jefferson (n.) Bles 1951 [London]

Mediterranean Murder (n.) Evans 1951 [Spain; Ship] US title: Killing Kin.

The Best Laid Plans (n.) Bles 1952 [England]

There’s Death in the Cup (n.) Evans 1952 [England]

Death Among the Tulips (n.) Allen 1953 [England]

The Evil That Men Do (n.) Allen 1953 [England]

And No One Wept (n.) Allen 1954 [England]

Poison in Paradise (n.) Allen 1955 [England]

A Reason for Murder (n.) Allen 1955 [England]

Murder at Mid-Day (n.) Allen 1956 [Spain]

Relative Murder (n.) Allen 1957 [England]

The Simple Way of Poison (n.) Allen 1957 [Oxford]

Epitaph for a Nurse (n.) Allen 1958 [England] US title: A Victim Must Be Found.

Poisoned Chalice (n.) Long 1959 [England]

To Cease Upon the Midnight (n.) Long 1959 [England]

The Thin-Spun Life (n.) Long 1960 [England]

Candidates for Murder (n.) Long 1961 [England]

He Had to Die (n.) Long 1962 [England]

Murder Cries Out (n.) Long 1968 [England]

Wed 16 Jul 2008

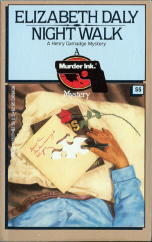

ELIZABETH DALY – Night Walk.

Dell, paperback reprint; Murder Ink series #55; 1st printing, December 1982. Hardcover first edition: Rinehart & Co., 1947. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, February 1948. Other paperback edition: Berkley F811, 1963.

A scarce book, relatively speaking. On ABE at the moment there are only 24 copies of all of the various editions combined. The “Murder Ink” series is a nice set to own, by the way. Wouldst that a mass-market publisher would consider doing today a long series of classic detective novels like this one, with a parallel and equally long one presented under the auspices of the “Scene of the Crime” bookshop on the West Coast.

Authors like Sheila Radley, V. C. Clinton-Baddeley, W. J. Burley, Douglas Clark, Colin Watson, and Patricia Moyes (Murder Ink); and Gladys Mitchell, Anthony Berkeley, Alan Hunter, and Gwendoline Butler (Scene of the Crime). Hardly any of them even in print today.

I’ll forgo my usual bibliographic discussion of the author, Elizabeth Daly. You can read the preceding review for that. Even though I read The Book of Lion over four years ago, the same kinds of feelings were evoked this afternoon and evening in finishing up Night Walk. A strong sense of nostalgia for the past, quite definitely, but there’s also (as I suspect in all of Daly’s fiction) an unmistakable love of things literary, bookish, and yes, libraries, where a portion of the current book takes place.

The scene is a small, isolated town in Westchester County, New York, which even though perhaps less than 50 miles from Manhattan, lives (or did in 1947) almost as though in a different, earlier era, and obviously in a far different place. A place where, if a murder occurs, it can be blamed on a tramp. A homicidal maniac, more likely.

The first four chapters, in fact, do nothing more than to follow the trail of the killer, first to a small scale rest and rehab facility for the rich and well-to-do, then the aforementioned lilbrary, then the local inn, and then and only then, to the home of the Carringtons’, where the senior member, an invalid, is later found dead in his bed.

Henry Gamadge is called in on the behest of a friend who finds himself caught up by accident by the police, a stranger to the area, but with an ulterior motive he’d rather not make public.

Gamadge, having an in with the police, a friend on the force in the city having put in a good word for him, does his usual low key type of investigation. In fact, the first 100 pages he’s on the job seem to be nothing more than retracing the steps of the killer on the path connecting his (or her) various stops along his way. Nothing seems to escape Gamadge’s attention, however.

To the reader, though, the lack of a “Watson” is a bit of a frustration, as we see what Gamadge sees, but we do not have access to his thought processes. On the other hand, however, there are none of those “You know my methods,” tossed off to his subordinates as if only to tease us.

It’s a trade-off, of course, and if I were to read more of Elizabeth Daly, I think I might eventually catch on to the way she includes her clues — all very fair and above board, I might very well make sure you understand.

What it also means is that it takes the last 18 pages or so for Gamadge to explain all, and ’tis nice, the explanation is, indeed. One wishes perhaps only more stage presence from Clara, otherwise known as Mrs. Gamadge. She comes to Frazer’s Mills only at the end of the book, appearing on only one or maybe two of the pages in the last 18.

Plotwise, I might mention a small couple of glitches in the summing up or the previous telling of the tale, but they’re so minor, for what good reason, I ask myself now, should I bring them up now? So I won’t, no more than I already have.

Wed 16 Jul 2008

ELIZABETH DALY – The Book of the Lion.

Bantam paperback, 1st printing, 1985. Hardcover edition: Rinehart & Co., 1948. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, September 1948. Earlier paperback editions: Bestseller Mystery #112, circa 1949; Berkley F700, circa 1963.

For a lady who didn’t start writing mysteries until she was in her early 60s, Elizabeth Daly was one of the more prolific author in the 1940s, publishing sixteen adventures of Henry Gamadge, the leading character in each of her books, during the twelve year period beginning in 1940 and ending in 1951.

It’s doubtful, though, if any but the most dedicated of mystery readers know of her work today. For the volume of work she did, Elizabeth Daly seems to be under-appreciated and all but forgotten. According to Amazon, only one of her books is currently in print: Unexpected Night (Otto Penzler’s Classic American Mystery Library, 1994).

And I’ll confess that in spite of many opportunities to do so, this is the first of her novels that I’ve read, and I can’t tell you why. In case, you’ll have to take the comments that follow as being based on a sample of size one, no more (and no less).

What Gamadge does (or did) for a living, precisely, based on this wispy, lightweight bit of mystery, escaped me for a while. He is called upon to look at a collection of letters that might have some value, even though he gently protests that he is not really qualified. He is later described as a graphologist – a handwriting expert – not to mention a noted criminologist (page 41). What he really seems to be, and he has a laboratory to back up this up, is an expert in old and rare books.

All of which lends a strong literary flavor to the case that follows. The widow of a famed poet and playwright, but not in any financial sense, has the husband’s letters, but before Gamadge can view them, she has them sold and bundled out of her brother-in-law’s house, sight unseen.

The end of the matter, perhaps, but Gamadge senses there was more to the sale than met the eye. He is proven right, although not in any way the police can follow up on, when the last person the dead man visited before his unsolved death also is found dead, an apparent suicide, and it takes Gamadge’s mild-mannered investigations to bring some closure and finality to the matter.

Gamadge is the epitome of the genteel, bookish detective, the pure amateur, and he is very clever in the way he figures things out and puts the pieces of the puzzle together – and I still haven’t figured out how he knew what and when nor how.

“The Book of the Lion,” by the way, would be a fabulous find, if it were ever found – especially in manuscript form as one of the lost books of Chaucer – and that is what piques Gamadge’s interest more than anything else, even if the chances are nearly one hundred percent that it’s a forgery.

Even if the plot is flimsy and gossamer thin, Daly’s characters are perfectly described, even those the most minor, and she has a sense of humor that can often catch you unaware. Gamadge’s wife Clara, who does not appear often enough in this novel, is a charming young woman who seems to adore Henry.

I particularly liked the following exchange, from page 112. Clara and Henry are talking about the beautifully naive young cousin of the widow who had the letters:

“And she loves to ride in taxis,” said Gamadge, “and I wish her taste in sandwiches were better. Still, they’re cheap.”

Clara said calmly, “Henry loves her because she’s a victim and doesn’t resent it.”

“Doesn’t know it,” Gamadge corrected her. “There’s nothing more beautiful than a martyr who isn’t aware of the fact.” He picked up Clara’s hand and held it against his cheek. As he laid it down again, she said: “I can’t imagine what you mean.”

“That’s what I mean.” Gamadge was laughing too.

— January 2004

[UPDATE] 07-16-08. Four and a half years later, and there aren’t any of Elizabeth Daly’s books in print. I’m guessing, but I imagine both she and Henry Gamadge are even less well-known now than they were then. Tastes change, I know, but it’s still a shame.

And in the “credit where credit is due” department: The cover of the Bestseller edition came from www.bookscans.com, a website with a most worthy goal: to display the covers of every vintage paperback ever published in the US through 1970 or so. I sent Bruce Black, the proprietor, a few he’s missing earlier this week, and if you’re a collector, you might consider doing the same.

[UPDATE] 07-23-08. Good news! I was in error when I said Daly is no longer in print. See the comment left today by Les Blatt.

Tue 15 Jul 2008

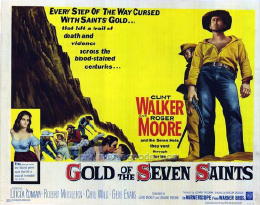

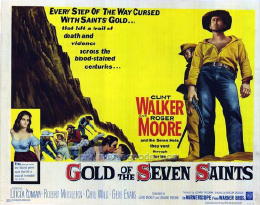

GOLD OF THE SEVEN SAINTS. Warner Brothers, 1961. Clint Walker, Roger Moore, LetÃcia Román, Robert Middleton, Chill Wills, Gene Evans. Based on the novel Desert Guns by Steve Frazee; co-screenwriter: Leigh Brackett. Director: Gordon Douglas.

Desert Guns was a paperback original (Dell First Edition A135, 1957) which I own and which I really ought to read. For now, this movie that’s based upon it will have to do. Any resemblance between film and book, however, may be (as usual) coincidental.

But however strong their relationship is in the book, Clint Walker and Roger Moore certainly make a good pair of friends in the movie, a small western epic of an adventure filmed (unfortunately) in black-and-white. Walker plays Jim Rainbolt, the senior of the two fur-trapping partners, while Moore is Shaun Garrett, his protege, so to speak, a young Irish cowboy who’s a bit wet behind the ears, and has a propensity to neither stop talking or (believe it or not) singing throughout the film.

One reviewer on IMDB claims their relationship borders on the homoerotic, but I don’t know. I guess you have to be looking for subtexts such as this, but if you’re interested in following him up on his claim, you can go read his long post for yourself.

Which not to say that you cannot find one or the other bare-chested in this film, and at least one of the photos that I’ve found to show you will back me up on this. The two of them make a good team, Clint Walker doing the TV show Cheyenne (1955-1962) at the same time as this movie, and Roger Moore just finishing a run as Beauregarde Maverick on that other Warner Brothers TV western series, but not yet known as The Saint.

What gets them into trouble in Gold of the Seven Saints is not their fur-trapping activities, but the 250 pounds of gold they’ve come across while doing so. This is a lot of weight to carry around, of course, and while trying to steal a horse while passing by a small town on their way to Seven Saints (the town where they’re headed), Shaun is cornered and buys his way out of trouble (and gains the horse) with a small nugget he’s carrying with him to clinch the deal.

Which is not a good idea. Almost immediately the two of them are on the run with a gang of thieves on their trail. Gene Evans is McCracken, the villainous leader of the bunch, and hardly anybody played a meaner, tougher western villain than Gene Evans. Chill Wills plays a doctor with an equally villainous thirst for whiskey, and Robert Middleton is a perhaps overly friendly Mexican bandit named Gondora. Both come to the two men’s rescue, or so they say.

There is only one female role of any consequence in this movie, and that’s Tita (LetÃcia Román), apparently Gondora’s “ward.” (I did not catch the full details, but Gondora is willing to sell her to the one of the pair who makes the higher offer.)

Once again it is a pity that a wide screen movie filmed with such spectacular scenery in the background was not done in color. The plot itself is fairly straight-forward. You’ll watch this for the players, all of whom seem to be having a good time.

As a quick PostScript, I’m probably not the only one who has wondered why Clint Walker did not have a more successful movie career than he did. Perhaps it was just a matter of being typecast as a Western player, and unlike Clint Eastwood, say, he never quite found the role that shifted gears for him.

Tue 15 Jul 2008

RICHARD S. WHEELER – The Witness.

Signet, paperback original; 1st printing, July 2000.

If you’re as old as I am, you might remember radio programs such as Suspense, Inner Sanctum or The Whistler, all of which opened with an all-seeing, all-knowing narrator — The Man in Black, Raymond, or the never named Whistler. These fine gentlemen were never part of the story, or if so, it was seldom, but it was their wry comments that always spurred the listener’s interest onward.

In The Witness, it’s western postmaster Horatio Bates, the Observer, who tells this story and makes a small but still significant role in it — the first of others to come, perhaps. Who knows more what goes on in small towns such as Paradise, Colorado, circa 1890, than the man through whose offices all the mail flows?

Bank accountants are also privy to many secrets, and Daniel Knott is no exception. Amos Burch, the banker, founder of the town and its primary benefactor, is the man who Knott sees late at night, in his office, with a woman, not his wife.

Knott is promoted, no quid pro quo stated, but it’s certainly understood. But when Amos Burch’s wife seeks a divorce, she needs a witness. And an honest man.

Burch, being a desperate man, turns to desperate measures. What follows is a small but powerful morality tale, the issues being honor, honesty and justice — and not all of them seem to be compatible with each other.

It’s also an old-fashioned sort of tale, flawed only by one character’s reaction to an ensuing development, one quite opposite to what I had expected. But given a tiny measure of suspended disbelief, here’s a book that can be read (if not devoured) in an evening’s time.

— September 2000 (slightly revised)

[UPDATE] 07-15-08. I’m not sure whether a book called Restitution (Signet, 2001) is the next book in the series or not, but it has the same cover design and mentions The Witness on the front cover. Whether there were others, I do not know.

« Previous Page — Next Page »