July 2008

Monthly Archive

Mon 7 Jul 2008

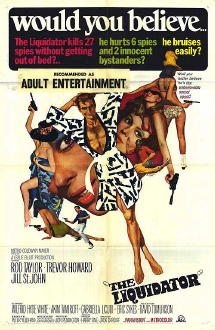

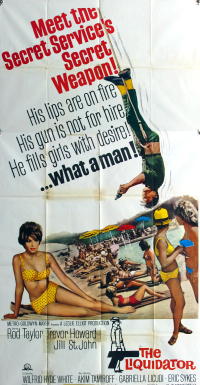

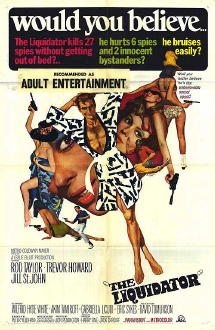

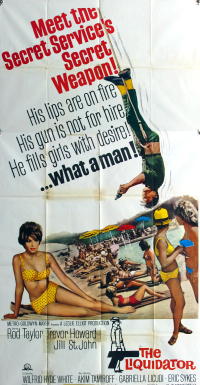

THE LIQUIDATOR. MGM, 1965. Rod Taylor, Jill St. John, Trevor Howard, Wilfred Hyde-White. Song over opening credits: sung by Shirley Bassey. Based on the novel of the same name by John Gardner. Director: Jack Cardiff.

Anti-hero secret agent Boysie Oakes has come up before on this blog, back when I read and reviewed Understrike, a later book in the series. That’s when I also listed all of the books in the series, so I needn’t do it here.

But I will repeat myself a bit by describing how I saw Mr. Oakes back then:

“The gimmick in the Boysie Oakes books […] is that as a spy, he’s supposedly inept, a coward who’s wracked with fear and stomach cramps at the thought of confronting the enemy, and a consummate womanizer. Or in other words, the direct opposite of Bond, save maybe the last category, although Bond usually stuck to one girl per book (didn’t he?).”

I also wondered about how Mr. Oakes got into the spy business in the first place, if he’s that inept and that much of a coward. Well, wonder no more, Mr. Lewis. The opening scene of the movie version of The Liquidator, filmed in black-and-white (with the rest of the movie in color), tells us exactly that. In the closing days of World War II, during the liberation of Paris, Boysie Oakes (Rod Taylor) accidentally saved the life of a British agent named Mostyn. See below and to the right:

Mostyn (Trevor Howard), never one to forget favors like that, but also not knowing how accidental his rescue was, calls on Boysie much later on to fill a new position in his Department, that of assassin, to eliminate those embarrassing people (double agents and the like) who would provide the press with more scandals, either by defecting or being arrested before they could defect.

Tempted by the promises of a mid-60s Hugh Hefner life of luxury when not working, even before he knows what “working” actually means, Boysie accepts. Bad move. How does he get out of actually doing the work? In the most delightfully engaging way – assuming of course you agree that the victims actually need to be, um, liquidated.

There is some satire involved here, as well as a slight touch of spoofery, and by this time half the movie is over. Of course there is another hour to fill, and with beautious Jill St. John (as Iris, Mostyn’s right-hand assistant) on hand to accompany Boysie on a strictly unauthorized trip for two to the Riviera, you’d think it would be filled most handsomely.

Not so. The people who put out the film thought they needed a plot, but the plot they give us is pure pap. Things do not go nearly as well as Boysie had planned. First he’s kidnapped (amusingly before anything serious happens in the bedroom), then released and/or allowed to escape, then sent off on a fool’s mission to do some serious damage back in the UK.

I’ve not read The Liquidator, the book, but at least one source says the movie people actually followed the book fairly closely. Perhaps they did, but they missed something, that something perhaps being that in spite of the movie being largely a spoof – which it definitely is until the shooting starts …

That’s it. That’s exactly when things started going wrong. Right then, when the movie people began to make a straight (but still more than a little goofy) action picture out of what until then was a mild and gentle satirical poke at Mr. Bond.

One other note. In the book I read, as you may recall from the review excerpt above, Boysie was described as being a coward.

That’s hard to play on the screen, so that part was downplayed, or so it seems to me. Rod Taylor simply plays Boysie as a good-natured chap, a fellow who’s rather inept (as also previously described) and gets sick in airplanes (and you know where that will lead) but this is about as far into that direction the movie goes.

This was the only film version of the character that was ever made.

Sun 6 Jul 2008

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

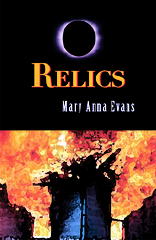

MARY ANNA EVANS —

Relics. Poisoned Pen Press; trade paperback, Feb 2007 trade paperback; hardcover edition, August 2005.

Effigies. Poisoned Pen Press, hardcover, January 2007.

These two novels, the second and third in a series, feature Faye Longchamp, an archaeological graduate student. In Relics, she’s directing a project on an ethnically isolated Alabama group, the Sujosa, who have shown an unusual resistance to diseases that include AIDs, while in Effigies, she’s part of a team excavating a site in Neshoba County, Mississippi, where the Choctaw nation is thought to have been born. When mysterious deaths occur in each case, it’s left to Faye to investigate.

Evans’ style is a bit heavy at times, with the scientific data weighing somewhat heavily on the narrative, but Faye is talented and possessed of a strongly independent mind that, coupled with a natural empathy for the native cultures she is investigating, make her a most sympathetic protagonist. The interaction with other members of the team and with the local population are thorny in both novels, and I found these both emotionally and intellectually satisfying.

[COMMENT] There is one earlier book in the series, as Walter mentions: Artifacts (2003); and one more recent one: Findings (2008). — Steve

Sat 5 Jul 2008

In her review of Round the Fire Stories, by Arthur Conan Doyle, posted here in May a year ago, Mary Reed began by saying:

None of the

Round The Fire Stories features Mr. Sherlock Holmes, although two mention anonymous letters to the press presenting solutions which some readers believe to have penned by the great detective himself (“The Man With the Watches” and “The Lost Special”).

And then in a footnote, she later added the following:

In “The Man With The Watches” we see: “There was a letter in the

Daily Gazette, over the signature of a well-known criminal investigator…”

“… and then we have “The Lost Special,” in which we learn of a letter: “… which appeared in the Times, over the signature of an amateur reasoner of some celebrity at that date, attempted to deal with the matter in a critical and semi-scientific manner. An extract must suffice, although the curious can see the whole letter in the issue of the 3rd of July.

“‘It is one of the elementary principles of practical reasoning,’ he remarked, ‘that when the impossible has been eliminated the residuum, however improbable, must contain the truth’.”

And I think we’ll agree the second letter in particular has his grammatical fingerprints all over it, but it raises another question: why didn’t Conan Doyle write these two adventures as Holmes stories? Were these stories written during a period when he was thoroughly tired of his own creation?

[WARNING: SOME PLOT ELEMENTS MAY BE REVEALED.]

In a comment left last April, and inexplicably never acknowledged by me until now, Brian Gould replied by saying:

Mary:

You ask, “Why didn’t Conan Doyle write these two adventures as Holmes stories?”

A clue to the answer, I believe, is that in both cases the unnamed letter writer was wrong. In “The Lost Special,” the train had been driven onto one of the four side lines of which it was earlier remarked that they “may be eliminated from our inquiry, for, to prevent possible accidents, the rails nearest to the main line have been taken up, and there is no longer any connection.” The villains had temporarily relaid the missing rails.

In “The Man With The Watches,” nobody jumped from one train to another. The dead man had been in the Euston to Manchester express all along, but had removed his disguise before his accidental killing, which occurred when his criminal associate attempted to shoot a third man who had joined them in their compartment but missed.

Doyle’s intention, surely, is humorous. He is simply making fun of his own creation, Sherlock Holmes, who does not usually commit such blunders.

Kind regards,

Brian Gould

>>>>>>>

My apologies to Mr. Gould for not pointing out this very useful reply until now. My only excuse is that I was out of town attending the Bordentown pulp and paperback show around the time his comment was posted, and I suspect that in the rush to catch up when I was back here at home, I simply failed to.

But here’s what I discovered that prompted my attention back to “The Lost Special” again, a rare find: one the “missing” episodes of Suspense, one of Old Time Radio’s best-known, and longest-lasting mystery programs.

I won’t post a link directly to the MP3, but I strongly recommend you go to Randy Riddle’s podcast blog and listen to it there, along with more information about both the disk and the program Of special note, until he found the disk, the program may not have been listened to in over 60 years, a “lost special” in and of itself. Excepted from Randy’s comments, here’s the basic info:

Unheard publicly since September 30, 1943, we bring you Orson Welles starring in “The Lost Special” a “tale well calculated to keep in you Suspense!.” Originally broadcast on the CBS radio network, but now lost, the version heard here was distributed by the Armed Forces Radio Service as program 24 in the Suspense series.

“The Lost Special” is based on a Sir Arthur Conan Doyle story and concerns a train that mysteriously disappears. The story was also used on the series Escape on February 12, 1949, so it may seem familiar. (You can give it a listen here.) However, in the “Suspense” version, the story is told by the main character and framed as a broadcast by a condemned man that will reveal the identity of persons responsible for certain crimes.

[…]

Orson Welles appeared in the series Suspense eight times between 1942 and 1944 in such classics as “The Hitchhiker” and “Donovan’s Brain.” One of Welles’ performances, “The Lost Special,” was thought to be one of about thirty-five Suspense programs missing out of over 900 broadcast during the run of the series.

Go visit, listen, and enjoy!

Fri 4 Jul 2008

CHARLES L. LEONARD – Sinister Shelter.

Unicorn Book Club; reprint edition. Originally published by Doubleday Crime Club, 1949. Digest paperback reprint: Bestseller Mystery B141. Pulp magazine reprint: Two Complete Detective Books, May 1950 (probably abridged).

One way you can read mystery and detective novels from the late 1940s and early 50s, if you can’t come across them in any other way, is to find them in hardcover book club editions, either from the three-in-one Detective Book Club, or the four-in-one volumes that came from the Unicorn Mystery Book Club.

Of the two, the Unicorn Books were classier in appearance, and they look very handsome on the bookshelf. They didn’t last nearly as long as their competitors, however, including of course the Dollar Mystery Guild, which eventually came along. (And still is going strong today, although you can certainly forget the dollar part of their name.)

In any case, without going further into their history (for now), I just bought about 20 of the Unicorn books on eBay, and over the next few weeks I’m planning on using them for reading material. Whether I skip around or read whole volumes at a time, I haven’t decided, but if it makes any difference, I think I’ll try reading this particular grouping all the way through. Stay tuned.

In real life Charles L. Leonard, author of eleven private eye Paul Kilgerrin novels, of which this one, was M. V. Heberden, who also wrote two other series of PI novels under that name, one featuring Desmond Shannon (17 books), the other being Rick Vanner, who appeared in three.

I’m not sure when the secret came out, but I imagine some eyebrows were raised when the initials M. V. were revealed to stand for Mary Violet. It’s been a while since I read any of them, but what little bibliographic information is about her books on the Internet suggests that they were tough, rugged and a little hard-boiled, reminiscent not at all of “shrinking violets.”

While nominally a private eye, in this particular book Kilgerrin given an assignment by the government to help stop a flood of illegal immigrants from coming into the US after World War II. And from the list of titles he appeared in, he seems have been an undercover spy much more often than he worked out of an office where good-looking women who came in were apt to be his clients.

Here’s a list of the Kilgerrin books. I think you’ll come to the same conclusion as I did. (All of the books were first published in hardcover by Doubleday Crime Club.)

Deadline for Destruction (1942)

The Stolen Squadron (1942)

The Fanatic of Fez (1943)

Secret of the Spa (1944)

Expert in Murder (1945)

Pursuit in Peru (1946)

Search for a Scientist (1947)

The Fourth Funeral (1948)

Sinister Shelter (1949)

Secrets for Sale (1950)

Treachery in Trieste (1951)

Not that there aren’t good-looking women involved, at least in Sinister Shelter. While he is working undercover to get a line on the people smugglers, Kilgerrin befriends the members of a refugee family who are trying to make their way into the United States via Argentina.

Among them is a young widow and her young boy who are living with her husband’s parent, said husband having disappeared after being arrested by the Nazis some time before. Kilgerrin is kind and gentle with the family, especially with Irma, and if he is hard-boiled about some other things, with her he does not seem to be.

The essence and general ambiance reminded me more of Hammett than it did Chandler, and for a long time, it was difficult to understand why. (I’ll return to this later.) Kilgerrin works with a firm goal in mind, but he has the capability of being able to improvise quickly, such as when the elderly father meets someone the family had known well back in Austria.

Marie Louise, now Louise Ritter, is the other woman in the story, and while her strong, enigmatic presence shifts the story quickly into second gear, it will occur to more than one reader, I am sure, that while coincidences like this often happen in the real world, fiction is never quite that strange.

In a way, there is a morality play going on. How does one comport oneself in the face of tyranny, the elderly father wonders on page 121, one man, acting alone, against evil? Kilgerrin himself tries to be understanding with Irma, but often finds himself frustrated when she cannot forget the past, when it stays with her and she cannot free herself from it.

The puzzle presented by the novel’s other lady of mystery gradually absorbs more and more of his attention. Kilgerrin has more in common with Louise Ritter, and he soon realizes it, making the question of how deeply she is involved with the smuggling gang all the more a matter of importance. (This could have been handled, unfortunately, somewhat more eptly.)

They are two entirely different women, and to Kilgerrin each is a mystery in different ways. The scene in which he last sees Irma is when (for me) the Hammett-Chandler comparison suddenly snaps into focus.

There is very little action, surprisingly enough, until the end. Character studies need some patience on the part of their readers, and that’s what, in large part, this story is comprised of. On the other hand, just to be sure that you know there is one, I’m going to quote the last few lines of the book, at which point in time the primary antagonist has been identified and is being discussed.

I’ve tried to be very careful in setting this up properly. If I’ve done it correctly, this will demonstrate, more than anything else, that there’s more involved here than character studies.

“… There are still gaps,” Morengo ended unhappily. “It is a pity […] is dead.”

Kilgerrin shook his head. “When anyone with that much guts goes wrong, he or she has got to be killed,” he said.

— April 2005

[UPDATE] 07-04-08. Since I don’t imagine you can make them out in the small image shown, the other three books in the same Unicorn volume as this one are: Drop Dead, by George Bagby; Tough Cop, by John Roeburt; and The Girl with the Hole in Her Head, by Hampton Stone.

In spite of the promise I made in the course of this review, I never did get around to reading any of these. On the other hand, the book is still here on the table next to the computer and keyboard where I’m typing away. That must mean something, mustn’t it?

The other reason, of course, for retrieving this review from the archives, is the preceding post, the “mystery author” turning out to be Mary Heberden, aka M. V. Heberden, aka Charles L. Leonard. More on her shortly, I hope — what little is known about her so far.

Fri 4 Jul 2008

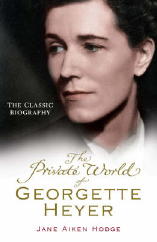

A distant relative of this female author recently asked me if I had any information about her. Unfortunately, other than the list of books she wrote, I didn’t. It seems, though, that the following photo has recently surfaced on the Internet, helping to prompt the inquiry, and I thought you’d like to see it, too.

There are no prizes for this contest, but before I tell you the little that’s known about her, I thought I’d see if anyone recognizes her, especially in light of the fact that such a beautiful woman later became, believe it or not, a hard-boiled P.I. writer.

Between 1939 and 1953 she wrote 21 novels under her own name, most of them with one private eye leading character, and 11 more under a pen name, all of these cases tackled by another PI.

Maybe this is too much information, making the contest too easy, but if I didn’t tell you anything, I don’t think anyone would come up with the answer at all!

Thu 3 Jul 2008

GEORGETTE HEYER – No Wind of Blame. Bantam; paperback reprint, September 1971. UK hardcover first edition: Hodder & Stoughton, 1939. US hardcover: Doubleday Crime Club 1939. Many other paperback reprint editions in both countries, including the bottommost one shown below (Arrow, UK, trade pb, 2006).

This is one of those small village murder mysteries which the British are known so well for. Georgette Heyer, born in 1902 and died in 1974, is known today largely for her historical romances, most of them from the Regency era, and mostly still in print.

Back in the 1930s, though, she also wrote a worthy amount of mystery fiction. (Of the 25 titles listed for her in Al Hubin’s Revised Crime Fiction IV, a rough reckoning is that 12 of them are detective novels; the rest appear to be historical fiction with some crime content.)

Her primary detectives were Superintendent Hannasyde and Inspector Hemingway; No Wind of Blame is one of the latter’s cases, although Hannasyde, his superior, makes a one or two paragraph cameo appearance, not so noted in CFIV.

The story begins with a visit to the Carter home of an Georgian (South Russian) prince, a gentleman forced from his homeland, and (quite obviously) in look of a good catch for a wife. That Ermyntrude Carter is already married seems to make no difference to him. Wallis Carter is rather worthless as a husband, quite dependent financially on his wife, who sighs and complains but sadly puts up with his profligate ways.

And it is Wally who is shot by a rifle while crossing a bridge as he is making his way to a neighbor’s house, where another make-some-money-quick scheme is being hatched. There are clues and suspects galore, none of the latter glaringly obvious, with the alibis of each are equally suspect.

The novel could be broken down in three parts, with the murder not occurring until page 78. The long opening section is devoted to introducing the players, and here is where Ms. Heyer excels. Each of the participants in the ensuing drama is individually drawn, stereotypes perhaps, in their way, but with mannerisms and behavior strikingly real and brought to life with dialogue and keen-eyed observations.

Part two consists of the investigation, conducted first by the local inspector, and man named Cook, who soon finds himself in over his head, outmatched by the limited number of suspects in their own inimitable fashion (although not in collusion with one another). Called in soon enough is Inspector Hemingway of Scotland Yard, who manages, with a dash of humor, to a keep a lid on the proceedings, but barely.

Most notable among the inhabitants of Palings, the Carter home, and those flitting in and out is Mrs. Carter’s teen-aged daughter Vicky, prone to poses and primed with outfits for each one. “Delightfully flaky” is a phrase that might be used to describe her, and she is a handful, but no slow thinker is she, by no means. (More later on this.)

Part three, if you are still keeping track, is the solution, which is a disappointment. While the opening stanzas are slow to get started, at least in this reader’s opinion, once the investigation begins, the story begins at once to pick up speed and become what is called a rattlingly good read. But in spite of all the clues, pointing every which way, and all of the alibis, which turn out not to be so solid after all, all it takes is the right phone call, upon which the culprit is identified immediately, followed by some fairly rigorous reconstruction of the crime required to prove the case in court.

How it was done surpasses the question at that point of who it was who did it, and it is not nearly (in this case) as interesting.

The characters and dialogue are right on, however, and if the occasion arises to read another of Georgette Heyer’s detective stories, by all means, I will.

In closing, though, here’s a long sample. Vicky, the dead man’s stepdaughter is trying her best to become a suspect, for reasons that become clear soon after. From pages 162-164, then, with one very important clue just happening to be included. (Mary is the dead man’s ward and cousin; Hugh is a gentleman friend of the family, who is becoming more and more attracted to Vicky, in spite of her spritely ways.) [A tip of the topper to the assist from the Georgette Heyer website, where the folks responsible also thought this was a key passage.]

EXCERPT —

“Darling Mary, no one who’d ever seen you with a gun could possibly think you’d fired a shot in your life,” said Vicky, with lovely frankness.

“It’s a funny thing, but it’s not often you’ll find a lady who won’t behave as though she thought a gun would bite her,” remarked the Inspector. “But I understand you’re not like that, miss?”

Vicky’s seraphic blue eyes surveyed him for a moment. “Did the Prince tell you that?” she asked softly.

“It doesn’t matter who told me, miss. Do you shoot?”

“No! I mean, yes, in a way I do,” said Vicky, becoming flustered all at once. “But I practically never hit anything! Do I, Mary? Mary, you know it was only one of my acts, and I’m not really a good shot at all! If I hit anything, it’s quite by accident. Mary, why are you looking at me like that?”

Mary, who had been taken by surprise by the sudden loss of poise in Vicky, stammered: “I wasn’t! I mean, I don’t know what you’re talking about!”

“You think I did it!” Vicky cried, springing to her feet. “You’ve always thought so! Well, you can’t prove it, any of you! You’ll never be able to prove it!”

“Vicky!” gasped Mary, quite horrified.

Vicky brushed her aside, and rounded tempestuously upon the Inspector. “The dog isn’t evidence. He often doesn’t bark at people. I don’t wear hair-slides. I’d nothing to gain, nothing! Oh, leave me alone, leave me alone!”

The Inspector’s bright, quick-glancing eyes, which had been fixed on her with a kind of bird-like interest, moved towards Mary, saw on her face a look of the blankest astonishment, and finally came to rest on Hugh, who seemed to be torn between anger and amusement.

Vicky, who had cast herself down on the sofa, raised her face from her hands, and demanded: “Why don’t you say something?”

“I haven’t had time to learn my part, miss,” replied the Inspector promptly.

“Inspector, it’s a privilege to know you!” said Hugh.

Vicky said fiercely, between her teeth: “If you ruin my act, I’ll murder you!”

“Look here, miss, I haven’t come to play at amateur theatricals!” protested the Inspector. “Nor this isn’t the moment to be larking about!”

Vicky flew up off the sofa. “Answer me, answer me! I was on the scene of the crime, wasn’t I?”

“So I’ve been told, but if you were to ask me –”

“My dog didn’t bark. That’s important. That other Inspector saw that, and you do too. Don’t you?”

“I don’t deny it’s a point. It’s a very interesting point, what’s more, but it doesn’t necessarily mean –”

“I can shoot. Anyone will tell you that! I’m not afraid of guns.”

“You don’t seem to me to be afraid of anything,” said Hemingway with some asperity. “In fact, it’s a great pity you’re not, because the way you’re carrying on, trying to convict yourself of murder, is highly confusing, and will very likely land you in trouble!”

“There is a case against me, isn’t there? You didn’t think so at first, but the Prince told you that I could shoot, and you began to wonder. Didn’t you?”

“All right, we’ll say I did, and there is a case against you. Anything for a quiet life!”

Vicky stamped her foot. “Don’t laugh! If I’m not a suspect, you must be mad! Quick, I can hear my mother coming! Am I a suspect or am I not?”

“Very well, miss, since you will have it! You are a suspect!”

“Angel!” breathed Vicky, with the most melting look through her lashes, and turned towards the door.

Ermyntrude same in. Before anyone could speak, Vicky had cast herself upon the maternal bosom. “Oh, mother, mother, don’t let them!”

The inspector opened his mouth, and shut it again. Mary said indignantly: “Vicky, it’s not fair! Stop it!”

Ermyntrude clasped her daughter in her arms. Over Vicky’s golden head, she cast a flaming look at Hemingway. “What have you been saying to her?” she demanded, in a voice that would have made a braver man than Hemingway quail. “Tell me this instant!”

Wed 2 Jul 2008

FIVE GOLDEN HOURS. 1961. Ernie Kovacs, Cyd Charisse, George Sanders. Director: Mario Zampi.

Even though American comedian Ernie Kovacs was a great favorite of mine, he’s not the primary reason for watching this very slight comedy caper of a film made by a largely British crew, and after him, you have no guesses left at all.

Kovacs, of course, was much better known for his work on television, but who knows what sort of success in the movies he might have had, had it not been for his fatal automobile accident in January, 1962. He made only one additional film, a wacky comedy called Sail a Crooked Ship, which premiered just before his death and remains fondly in my memory as a Very Funny Movie.

Perhaps I should leave it there — in my memory, that is — as perhaps I should find it not nearly as side-splitting today as when I was a mere lad barely out of my teens. His mugging in Five Golden Hours is exactly how I remember him, and yet — I barely cracked more than a smile. Subtle, I don’t imagine he ever was.

He’s an assistant funeral director in Italy, you see, and what you might call a professional pallbearer, offering his abundant sympathies to bereaved widows for accommodation and reward: three of them — widows, that is — at the beginning of this movie.

Enter the Baroness Sandra (Cyd Charisse), having just lost her fifth husband, and about to be evicted from her small castle of her home. Enter Aldo Bondi, whose charm seems surprisingly (to him) ineffective. Until, that is, the Baroness decides that she may have a use for him after all.

All is not what it seems. Her latest husband had had a scheme, something to do with the five hours difference in time between financial centers on the continent and New York City, but as the scheme did not work out according to plan, the aforementioned creditors are beginning to circle around.

Aldo gladly offers to help. The lady, that is, not the creditors. Enter the rich widows who have most recently been supporting him. Exit the Baroness.

And then, at last, the twists in the plot begin, including an abortive (but funny) attempt at murder. Take George Sanders, for example, whom I have not mentioned before now, as there was no need to, as he does not show up until very nearly the next to the last reel, and then in only one room, the one in the mental institution where … just before one widow … and Bondi has to go off to the monastery where … I told you there were twists, didn’t I?

Too bad that they’re not very interesting ones, and none of them bring Cyd Charisse back on the set for more than another small glimpse or two. What a waste of on-screen talent. They really should have filmed this movie in color, too. Who wants to see the grand Italian countryside in black-and-white?

Wed 2 Jul 2008

Posted by Steve under

Authors1 Comment

Steve:

I was pleased to see your posting on Richard Ellington. In addition to being one of my favorite P.I. writers of the late 40s and early 50s, I got to know him personally in the mid 70s when he submitted a story to an MWA anthology Joe Gores and I were editing. The story, “Goodbye, Cora,” which is set on St. Thomas, appears in Tricks and Treats (Doubleday, 1976) and was Ellington’s last published fiction.

Duke, as everyone called him for the obvious reason, did indeed own and operate a small hotel on St. John, located on Gallows Point in Cruz Bay. The hotel is still there, though the new owners have expanded it into an upscale resort to take advantage of spectacular sunset and ocean views.

Marcia and I had the pleasure of staying at the Gallows Point Resort during a combination vacation and research trip five years ago. The restaurant there is called Ellington’s, no doubt as a tribute to Duke and his wife Kay.

The work involved in running a hotel is the reason he did very little writing during the last three decades of his life. Though he did mention in a letter that he’d been working on his autobiography off and on for many years, chronicling his life as a soldier, theatre and radio actor, radio announcer, radio and mystery writer, and hotel owner. The rather unwieldy title was Fathead, or “The Story of a Man Born the Year World Changed and Who is Now Going Like Sixty.” As far as I know, he never finished it. More’s the pity.

After Gores and I took “Goodbye, Cora” for Tricks and Treats, Duke invited us and our then wives down to Gallows Point for a free week’s lodging. We’d planned to accept, but for one reason and another the plans failed to materialize; so I never had the pleasure of meeting him in person. More’s the pity on that score, too. If he was anything like his letters, which I still have, he must have been quite a raconteur.

Attached is a photo of Ellington, from the back of the Exit for a Dame dust jacket.

Wed 2 Jul 2008

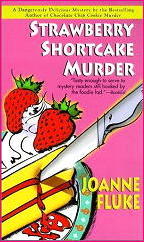

JOANNE FLUKE – Strawberry Shortcake Murder.

Kensington; paperback reprint, February 2002. Hardcover first edition: Kensington, March 2001.

By sheer happenstance — a fluke of luck, you might say [*] — I discovered that Joanne Fluke has had quite a varied writing career. She seems to have started out writing horror novels, beginning in the early 1980s: books with titles like The Stepchild, Video Kill, and so on. Then as Jo Gibson she began writing young adult novels in much the same vein: Slay Bells, My Bloody Valentine and more.

As “Kathryn Kirkwood” in the late 1990s she began to branch out in an altogether different direction: regency romances. And two years ago she seems to found her forte with the first in her Hannah Swenson mystery series, The Chocolate Chip Cookie Murder.

This is the second, with the third already out in hardcover, and if these books don’t at least make you hungry — recipes included — nothing will. Hannah runs a cookie shop in snowbound Lake Eden, Minnesota. Fluke makes it sound like a small town, and the way things are going, in a few more books, it will be even smaller. (Trend analysis at work.)

When the local basketball coach is found murdered after his last-minute substitution as a judge for a TV cooking contest, Hannah and her non-lookalike sister go snooping after the killer, even though Hannah’s boy friend (a cop) and Andrea’s husband (also a cop) do their best to discourage them.

A cozy sort of mystery novel, as comfortable as scarves and old shawls. Most of the appeal lies in the people, Hannah’s friends, relatives and neighbors, which constitutes 90% of the population of Lake Eden. The detective work is minor — there is an interval of time during which almost every reader will simply be screaming (non-verbally) for the obvious to dawn on Hannah and her sister.

Even so, it’s a fun read, to coin a phrase, and I think Fluke has something good going for her.

[*] I confess. Not luck at all. On page 181 of the paperback edition, the Lake Eden Regency Romance Club re-enacts a scene from one of Kathryn Kirkwood’s (unpublished?) regency romance novels. You can’t read this without at least cracking a smile.

[UPDATE] 07-02-08. I’m not very good at predicting track records of authors, but I was right this time. Just over six years later, there are now ten books and one novella in the series, and I don’t think Hannah Swenson will run out of recipes anything soon:

Chocolate Chip Cookie Murder (2000)

Strawberry Shortcake Murder (2001)

Blueberry Muffin Murder (2002)

Lemon Meringue Pie Murder (2003)

Fudge Cupcake Murder (2004)

Sugar Cookie Murder (2004)

Peach Cobbler Murder (2005)

Cherry Cheesecake Murder (2006)

Key Lime Pie Murder (2007)

Candy Cane Murder (2007) (a novella included in Candy Cane Murder;

other authors: Laura Levine & Leslie Meier)

Carrot Cake Murder (2008)

Tue 1 Jul 2008

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

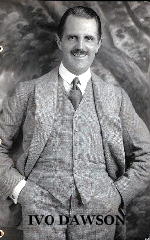

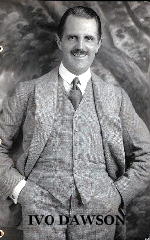

WADSWORTH CAMP – The Abandoned Room. Doubleday Page & Co., US, hardcover, 1917. Hardcover reprints: W. R. Caldwell: The International Adventure Library, Three Owls Edition, n.d. (this is the edition shown); A. L. Burt, n.d. Jarrolds, UK, hardcover, 1919. Silent film: Jans, 1920, as Love Without Question (scw: Violet Clark; dir: B. A. Rolfe; with Olive Tell as Katherine, James Morrison as Robert Blackburn, Mario Majeroni as Silas Blackburn, and Ivo Dawson as Carlos Paredes, the “Panamanian Sherlock Holmes”).

How was the murder accomplished in a room with both doors locked on the inside and the windows too high for someone to climb in without warning the occupant? Were what one character firmly believed were psychic forces at work in The Abandoned Room?

The Abandoned Room begins with an account of the discovery of the body of Silas Blackburn in that very bedroom, long shunned because of its history of family members dying there from various types of injury to the head. And this death was after Silas had been going around terrified out of his wits, but refusing to say why he was afraid or indeed who or what it was he feared.

Silas is the grandfather of cousins Katherine (who lives with him) and Bobby, who has been having what Camp politely calls a “lively life” in New York and is thus about to be cut out of his grandfather’s will, which otherwise would have left him a million or so with which to be even livelier.

As the story backtracks about 24 hours, Bobby and his good friend, the lawyer Hartley Graham, are talking at their club. Hartley is trying to persuade Bobby to give up his fast ways and go and see his grandfather at The Cedars, a lonely and eerie tumble-down country house.

Bobby agrees to do so but is prevented from catching the vital 12.15 train by a dinner appointment with Carlos Paredes, who brings along theatrical dancer Maria. Lawyer Graham strongly disapproves of Carlos, that “damned Panamanian”, and after reminding Bobby he has to catch his train leaves in disgust.

Next morning Bobby wakes up with his shoes off in a decrepit old house near The Cedars with no recollection of how he got there or indeed anything that happened after his dinner with Carlos and Maria the night before. Ashamed to be seen by his grandfather and cousin in crumpled evening dress and somewhat dazed condition he hoofs it for the railway station to return to New York.

On his way to the station he is met by county detective Howells, who more or less accuses Bobby of doing away with his grandfather in order to prevent the threatened changing of the will. Told to go to The Cedars to await events, Bobby finds his friend Graham already there and not long after Carlos shows up and invites himself to stay. It is a testament to their good breeding they do not tell him to be off although at times the reader will do the job for them.

What follows is a rich stew of events, including strange happenings in the candle-lit dwelling, haunting cries in the surrounding woods and outside the house, suggestions of ghostly presences infesting the decaying mansion, a woman in black glimpsed in the woods, and Bobby’s growing fear he somehow entered the locked room and murdered his grandfather in a drugged haze.

A tightening net of suspicion seems sure to bring him to trial for the crime. When one of his monogrammed hankies is found under the bed in which his grandfather died and his evening shoes fit a footprint under the window, it looks really bad for him — and he cannot summon any memories of the missing hours to his own defence.

My verdict: I really enjoyed this novel and thought the descriptions of the unhappy house and its run down grounds were excellent. The suggested supernatural element is conveyed beautifully, making this a work that would have made a wonderful Hitchcock film, in particular because of a terrific shock near the end when the explanation begins to be revealed.

If nothing else this old dark mansion mystery demonstrates that on the whole monogrammed hankies are probably best avoided. And how was the crime accomplished? The method is prosaic enough, but with a little twist from numerous similar explanations.

Etext: http://www.munseys.com/disktwo/abroomdex.htm

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Taken from Part 19 of the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

CAMP, (CHARLES) WADSWORTH. 1879-1936. Born in Philadelphia PA. A journalist, writer and foreign correspondent whose lungs were said to have been damaged by exposure to mustard gas during World War I. Father of writer Madeleine L’Engle, 1918-2007, q.v. Author of six titles included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. See below. [Films based on these books are omitted from this entry.]

The Abandoned Room. Doubleday, hc, 1917. Jarrolds, UK, hc, 1919.

The Communicating Door. Doubleday, hc, 1923. Story collection (ghost tales).

-The Forbidden Years. Doubleday, hc, 1930.

The Gray Mask. Doubleday, hc, 1920. SC: Jim Garth. Setting: New York. Collection of seven connected novelets, untitled. “Mystery novel of a detective who falls in love with the chief of police’s daughter.”

The House of Fear. Doubleday, hc, 1916. Hodder, UK, hc, 1917. Setting: New York; theatre. Also published as: Last Warning (Readers Library, 1929).

_The Last Warning. Readers Library, UK, hc, 1929. See: The House of Fear (Doubleday, 1916)

Sinister Island. Dodd Mead, hc, 1915. Setting: Louisiana.

« Previous Page