February 2009

Monthly Archive

Wed 18 Feb 2009

GEORGE BAXT – The Dorothy Parker Murder Case.

International Polygonics; reprint paperback; 1st printing, April 1986. Hardcover edition: St. Martin’s Press, 1984. Trade paperback reprint: IPL, November 1989.

I’ve been struggling to remember, but I think this is the first book by George Baxt that I’ve ever read. The Dorothy Parker Murder Case is the first of three series of detective novels he wrote, along with five stand-alone works of crime fiction. His series charcaters were:

1. Pharaoh Love: New York City homicide detective in New York, both black and gay.

2. Sylvia Plotkin and Max van Larsen: New York City author and police detective.

3. Jacob Singer: New York City homicide detective, later a 1940s LA private eye, or so I’ve been told.

While I was reading it, I didn’t realize that Dorothy Parker was Singer’s first recorded case. He and the celebrated Mrs. Parker had met previously when this case begins – that of the mysterious deaths of several Manhattan-based show girls — but when, how, and on what basis it happened they met was never the subject of a mystery novel of its own.

When Baxt, who died in 2003, was writing the Jacob Singer books, I was going through a phase in which I paid no attention to mystery fiction that had “real people” in them. I had no idea until yesterday that Baxt had written so many of them. (See the complete list at the end of this review.)

I can’t tell you why I had that particular prejudice. If I had a bad experience with a novel with a real person in it, it’s possible, but I simply don’t remember. Sometimes otherwise normal people do silly things.

I also have never done any reading about Dorothy Parker and the famed Algonquin Round Table, nor read any but the briefest poems among her huge accumulation of literary work. I suppose there’s enough time left in my life to make up for various deficiencies like this, and instead of writing reviews, I sometimes think maybe I really ought to be doing something about it.

In this book, which takes place immediately following the tragic death of Rudolph Valentino in 1926, the following real people appear, and I know I’m omitting some: Dorothy Parker, of course; her sleuthing partner, Alexander Woolcott; George S. Kauffman, in whose apartment the first dead girl is found; Robert Benchley; Marc Connelly; Judge Crater; Polly Adler; Edna Ferber; George Raft; Harold Ross; Flo Ziegfeld; Neysa McMein; Horace Liveright; Marie Dressler; Elsa Maxwell; Jeanne Eagels; and more.

Not that all of these have big parts, but if what George Baxt says about them and their whoring and drinking, it’s remarkable that any of them grew up to be famous. There are puns, zingers and witticisms in this book galore, nearly one on every page.

Picking a page at random, here’s a long passage that begins by describing Jacob Singer as he walks into Kauffman’s apartment to see the dead girl there in the bed:

He [Singer] spent money on clothes and general good grooming and forced himself to read Dickens, Henry James, and on one brief depressing occasion, Tolstoy. He attended the theater and concerts as often as possible, but the opera only under the threat of death. Mrs. Parker’s admiration for the man was honest and limitless. “Okay, Mr. Kaufman, what’s the problem?”

“I’ve got a dead woman in the bedroom.”

“I’ve had lots of those, but usually they get dressed and go home.”

They followed him into the bedroom. “Oh boy, oh boy. That is one ugly stiff.”

“She used to be quite beautiful,” said Kaufman. “Ilona Mercury.”

Singer pierced the air with a shrill whistle of astonishment. “I’d never guess. Would you believe just the other night I saw her in Ziegfeld’s revue, No Foolin’.”

“We believe you,” said Mrs. Parker.

Singer shot her a look. “No Foolin’ is the name of the show. It’s at the Globe.”

“Oh. I’ve been away.”

“Let’s get back to the other room. This is too depressing. Imagine a beautiful broad like that turning into such an ugly slab of meat. That’s life.”

“That’s death,” corrected Mrs. Parker.

Here’s another:

[Harold] Ross leaned forward and aimed his mouth at Mrs. Parker. “How come you’re so privy to all this inside dope?”

A puckish look spread across Benchley’s face. “Oh, tell me privy maiden, are there any more at home like you?”

He was ignored. Mrs. Parker was struggling with her gloves. “Last night when dining with Mr. Singer, I told him Alec and I were seriously considering collaborating on a series of articles about contemporary murders.”

Ross looked dubious. “You and Alec collaborating? That’s like crossing a lynx with a mastodon.”

“And why not?” interjected Woollcott. “Might be fun. Where are you off to, Dottie?”

“Where are we off to, sweetheart. Why, we’re off to Mrs. Adler’s house of ill repute as Mr. Singer’s companions. He’s picking us up in a squad car in a few minutes. If you’re a good boy, he’ll let you stand on the running board with the wind in your hair.”

The less said about the mystery the better, and you will have noticed that I’ve already done so. That’s not what you’re paying your money for this time around. For what it’s worth, of the real people above, George Raft fares the worst at the hands of Mr. Baxt’s typewriter. Of the people who weren’t real until Mr. Baxt came along, though, you may be sure that many of them fare much worse.

In summary, then, in case you’re wondering, do I intend to track down and read the rest of Jacob Singer’s adventures? Yes, indeed I do, and here’s a complete list of them, based on his entry on the Thrilling Detective website. (Not all of these are listed in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. I will pass the information along to Al Hubin.)

* The Dorothy Parker Murder Case (1984)

* The Alfred Hitchcock Murder Case (1986)

* The Tallulah Bankhead Murder Case (1987)

* The Talking Pictures Murder Case (1990)

* The Greta Garbo Murder Case (1992)

* The Noel Coward Murder Case (1992)

* The Marlene Dietrich Murder Case (1993)

* The Mae West Murder Case (1993)

* The Bette Davis Murder Case (1994)

* The Humphrey Bogart Murder Case (1995)

* The William Powell & Myrna Loy Murder Case (1996)

* The Fred Astaire & Ginger Rogers Murder (1997)

* The Clark Gable & Carole Lombard Murder (1997)

Tue 17 Feb 2009

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

If you’re interested in Cornell Woolrich and get Turner Classic Movies on satellite, I strongly suggest that, the next time it’s scheduled, you check out Blind Date (Columbia, 1934). It’s not based on anything Woolrich wrote and isn’t even a film noir, but this obscure little gem breathes the spirit of Woolrich’s early non-crime fiction like no other movie I’ve seen.

Ann Sothern stars as a young woman of Manhattan, supporting her parents and a kid brother and sister in the pit of the Depression. As in the country-western song she is torn between two lovers: her steady boyfriend (Paul Kelly), who is “shanty Irish” like herself, and the wealthy young playboy (Neil Hamilton) whom she met on the blind date of the title.

Anyone who’s familiar with the early Woolrich stories, and their recurrent theme that relationships and anguish are inseparable, is sure to feel that this movie must have been based on one of them.

(Homework assignment: read Woolrich’s 1930 tale “Cinderella Magic,” collected in my Love and Night, just before or after watching the movie.)

Even more amazing is the number of links between this film and Woolrich’s future. There’s a short and brutal scene at a dance marathon prefiguring the suspense master’s powerful 1935 tale “Dead on Her Feet.”

Second male lead Paul Kelly was to play the second male lead a dozen years later in the Woolrich-based “Fear in the Night” (1947).

The director, Roy William Neill, would later, and just before his death, helm Black Angel (1946), arguably the finest movie ever based on a Woolrich novel.

Even the title Blind Date figures in the Woolrich canon: first in his pulp story “Blind Date with Death” (1937), later as the new title for the 1935 story better known as “The Corpse and the Kid” and “Boy with Body” when, in 1949, Fred Dannay reprinted it in EQMM.

All these links are coincidences, of course, but what an eye-popping network of them!

Speaking of Fred Dannay, a Japanese film crew will soon be coming to America to make a documentary on Ellery Queen. Since this is the first segment of a projected series to be called The Great Mystery Writers, I assume (and hope) that the emphasis will be on Fred and his first cousin Manny Lee, not on the detective character whose name they chose as their joint byline.

I’m going to be involved in this project but exactly to what extent and in what capacity isn’t clear yet. For updates, stay tuned to this column.

Soon to be published by the ABA Press (that’s ABA as in American Bar Association) is an anthology entitled Lawyers in Your Living Room! which deals, as you must already have guessed, with the countless series about the legal profession that have graced or disgraced our TV screens for more than half a century.

As you also must already have guessed, I wrote the chapter on Perry Mason. There’s also a chapter on The Defenders, but most of the series discussed in the book are much more recent than Mason. For more details you needn’t wait for my next column, just google the title.

During much of the next week my eyes are going to be glued to the PDF of the second volume of The Dark Page, which I am checking over for author Kevin Johnson.

The first volume was a lavish coffee-table book dealing with those films noirs of the 1940s that were based on novels or short stories and with their literary sources.

The sequel covers the noirs of the Fifties and early Sixties and their literary sources, ranging from Dreiser and Hemingway and Graham Greene, through a slew of specialists in noir fiction — Horace McCoy, Steve Fisher, Dorothy B. Hughes, Ed McBain, John D. MacDonald, David Goodis and (need I mention?) Woolrich — to such long-forgotten pen wielders as Ferguson Findley and Willard Wiener.

Mickey Spillane, of course, gets full coverage. The choices of what films count as noir are at times quite unusual: The Bad Seed and the first version of Death of a Salesman are in, as is Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, but Psycho is out.

The illustrations aren’t part of my PDF but, if the first Dark Page volume is any indication, they’ll be stunning.

If you groove on Harry Stephen Keeler, the greatest nut who ever wrote a book, you’ll be pleased to hear that Strands of the Web, a collection that brings together the vast majority of his early short stories — not all because two or three remain lost — is about to be published by Ramble House.

Most of these tales were written between 1913 and 1916, when Keeler was in his early and middle twenties and just beginning to develop the webwork patterns of wild coincidence that were to become his trademark but the earliest story dates back to 1910 and the latest to 1962, a few years before his death.

You’ll find a few foreshadowings of his wacky webs now and then in this collection, but the prose is much more ordinary than the labyrinth sentences he eventually came to favor. The most noticeable influence on these stories is O. Henry, perhaps the most popular American short-fiction writer of all time, who died the same year Keeler first set pen to paper.

For more details, go to www.ramblehouse.com.

Mon 16 Feb 2009

EDGAR WALLACE AT MERTON PARK

by Tise Vahimagi.

Afforded only a footling footnote in the history of British cinema, the Merton Park Edgar Wallace films remain consistently enjoyable as a series of hectic penny dreadfuls, at times complication piles upon complication bewilderingly, but more often moving at a cracking pace. While not quite film noir, in true observation of the term, there is a grimy pleasure to be derived from these modest little dramas.

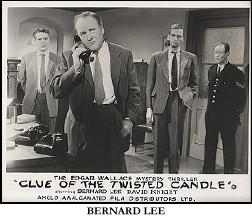

Though never entirely convincing, they do unfold with a quiet slickness, arousing curiosity, delivering a few plot-twist surprises, and displaying some competent performances. A pre-Bond Bernard Lee, for instance, shows up a few times as various Detective Superintendent types; and Hazel Court amuses herself as a very well-bred private eye in The Man Who Was Nobody (1960).

Merton Park Studios (1937 to 1967) was the prolific producer of the Edgar Wallace series of supporting features (released between 1960 and 1964), along with the similar Scotland Yard (1953-1961) and Scales of Justice (1962-1967) films.

This was the low-budget production world of a film-per-week schedule (up to 14 camera set-ups a day); the first Edgar Wallace film was released in November 1960 (in the UK); the 25th Wallace film went into production at the end of September 1962.

In 1960, Nat Cohen and Stuart Levy, managing directors of distributor Anglo Amalgamated (UK), acquired the film rights for world-wide distribution of the entire Wallace library. They gave the go-ahead to Merton producer Jack Greenwood (1919-2004) to make a �series’ of supporting features for their distribution circuit.

In his professional capacity, Greenwood may have been Britain’s Sam Katzman, keeping a firm hand on the purse strings and pushing cast and crew to the last penny’s worth. He was, thankfully, also producer of the realistic 1960 prison drama The Criminal (US: The Concrete Jungle), starring Stanley Baker, and, in 1967, became production controller on The Avengers series at ABPC Elstree Studios.

Merton Park Studios was based in a modest-size house in suburban south west London, employing a roll-call of British character actors, hired by-the-day (as well as some affordable European players), and utilizing the neighbouring streets and sites as economic locations.

Some 40 titles make up the run of Edgar Wallace films. Less than half were based on actual Wallace material, the rest consisting of original screenplays to supplement a saleable package under the Wallace introductory logo (a revolving bust of Wallace, sometimes tinted a bilious green, accompanied by twangy electric guitar music performed by The Shadows).

A list of the Edgar Wallace/Merton Park titles will follow this overview.

By the time the Wallace films started, Greenwood/Merton Park had already been producing a similar series of supporting programmers. Introduced by grim-faced journalist/criminologist Edgar Lustgarten (1907-1978) since 1953, the Scotland Yard series (produced until 1961) were sufficiently suspenseful police investigation dramas based on real-life cases (apparently).

The early films directed by Ken Hughes are interesting for their imaginative application of catchpenny production values. Since all the Wallace stories were updated to the 1960s, there is little to distinguish between the series; except perhaps that the Scotland Yard films often featured deadpan Russell Napier as the coldly businesslike detective.

Following on, the Scales of Justice series (released 1962 to 1967) added to Anglo’s distribution titles between Wallace productions. Lustgarten, again, introduced dark and dire case-file stories of crime-and-comeuppance with his customary solemnity.

The basic form and content of the three series was pretty much interchangeable, leading the later TV packages to often confuse the films’ origins. The UK experience remains that these films were originally produced for the cinema screen.

The US viewing experience, via TV presentations, has led many to believe that they were made for television. The Wallace films went to US TV as The Edgar Wallace Mystery Hour (or Theatre), usually trimmed to accommodate an hour slot (syndicated from c.1963).

Scotland Yard (39 x 26-34 min. films) was syndicated from 1955, and later shown via ABC from 1957 to 1958 in half-hour form. Scales of Justice (originally 13 x 26-33 min. films) probably supplemented the above TV packages.

Edgar Wallace films:

(The following are presented in order of production date, by year). I have also tried to give story source, where known.)

1960:

1. The Clue of the Twisted Candle. Bernard Lee, David Knight, Frances De Wolff. Screenplay: Philip Mackie; from the 1916 novel. Director: Allan Davis.

2. Marriage of Convenience. John Cairney, Harry H. Corbett, Jennifer Daniel. Scr: Robert Stewart; based on The Three Oak Mystery (1924). Dir: Clive Donner. [Follow the link for the first eight minutes on YouTube.]

3. The Man Who Was Nobody. Hazel Court, John Crawford, Lisa Daniely. Scr: James Eastwood; from the 1927 novel. Dir: Montgomery Tully.

4. The Malpas Mystery. Maureen Swanson, Allan Cuthbertson, Geoffrey Keene. Scr: Paul Tabori, Gordon Wellesley; based on The Face in the Night (1924). Dir: Sidney Hayers. [See NOTES below.]

5. The Clue of the New Pin. Paul Daneman, Bernard Archard, James Villiers. Scr: Philip Mackie; from the 1923 novel. Dir: Allan Davis.

1961:

6. The Fourth Square. Conrad Phillips, Natasha Parry, Delphi Lawrence. Scr: James Eastwood; based on Four Square Jane (1929). Dir: Allan Davis.

7. Partners in Crime. Bernard Lee, John Van Eyssen, Moira Redmond. Scr: Robert Stewart; based on The Man Who Knew (1918). Dir: Peter Duffell.

8. The Clue of the Silver Key. Bernard Lee, Lyndon Brook, Finlay Currie. Scr: Philip Mackie; from the 1930 novel (aka The Silver Key). Dir: Gerard Glaister.

9. Attempt To Kill. Derek Farr, Tony Wright, Richard Pearson. Scr: Richard Harris; based on the short story The Lone House Mystery (1929). Dir: Royston Morley.

10. The Man at the Carlton Tower. Maxine Audley, Lee Montague, Allan Cuthbertson. Scr: Philip Mackie; based on The Man at the Carlton (1931). Dir: Robert Tronson.

11. Never Back Losers. Jack Hedley, Jacqueline Ellis, Patrick Magee. Scr: Lukas Heller; based on The Green Ribbon (1929). Dir: Robert Tronson.

12. The Sinister Man. John Bentley, Patrick Allen, Jacqueline Ellis. Scr: Robert Stewart; from the 1924 novel. Dir: Clive Donner.

13. Man Detained. Bernard Archard, Elvi Hale, Paul Stassino. Scr: Richard Harris; based on A Debt Discharged (1916). Dir: Robert Tronson.

14. Backfire. Alfred Burke, Zena Marshall, Oliver Johnston. Scr: Robert Stewart. Dir: Paul Almond.

1962:

15. Candidate for Murder. Michael Gough, Erika Remberg, Hans Borsody. Scr: Lukas Heller; based on “The Best Laid Plans of a Man in Love” [publication date?]. Dir: David Villiers.

16. Flat Two. John Le Mesurier, Jack Watling, Barry Keegan. Scr: Lindsay Galloway; based Flat 2 (1924). Dir: Alan Cooke.

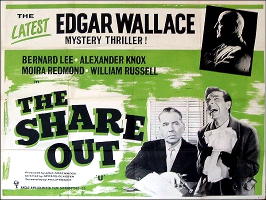

17. The Share Out. Bernard Lee, Alexander Knox, Moira Redmond. Scr: Philip Mackie; based on Jack o’ Judgment (1920). Dir: Gerard Glaister.

18. Time to Remember. Harry H. Corbett, Yvonne Monlaur, Robert Rietty. Scr: Arthur La Bern; based on The Man Who Bought London (1915). Dir: Charles Jarrott.

19. Number Six. Nadja Regin, Ivan Desny, Brian Bedford. Scr: Philip Mackie; from the 1922 novel. Dir: Robert Tronson.

20. Solo for Sparrow. Anthony Newlands, Glyn Houston, Nadja Regin. Scr: Roger Marshall; based on The Gunner (1928; aka Gunman’s Bluff). Dir: Gordon Flemyng.

21. Death Trap. Albert Lieven, Barbara Shelley, John Meillon. Scr: John Roddick. Dir: John Moxey.

22. Playback. Margit Saad, Barry Foster, Victor Platt. Scr: Robert Stewart. Dir: Quentin Lawrence.

23. Locker Sixty-Nine. Eddie Byrne, Paul Daneman, Walter Brown. Scr: Richard Harris. Dir: Norman Harrison.

24. The Set Up. Maurice Denham, John Carson, Maria Corvin. Scr: Roger Marshall. Dir: Gerard Glaister.

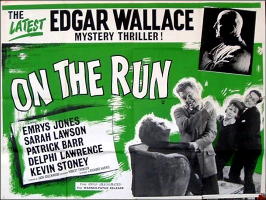

25. On the Run. Emrys Jones, Sarah Lawson, Patrick Barr. Scr: Richard Harris. Dir: Robert Tronson.

1963:

26. Incident at Midnight. Anton Diffring, William Sylvester, Justine Lord. Scr: Arthur La Bern. Dir: Norman Harrison.

27. Return to Sender. Nigel Davenport, Yvonne Romain, Geoffrey Keen. Scr: John Roddick. Dir: Gordon Hales.

28. Ricochet. Maxine Audley, Richard Leech, Alex Scott. Scr: Roger Marshall, based on The Angel of Terror (1922, aka The Destroying Angel). Dir: John Moxey.

29. The �20,000 Kiss. Dawn Addams, Michael Goodliffe, Richard Thorp. Scr: Philip Mackie. Dir: John Moxey.

30. The Double. Jeannette Sterke, Alan MacNaughtan, Robert Brown. Scr: Lindsay Galloway; from the 1928 novel. Dir: Lionel Harris.

31. The Partner. Yoko Tani, Guy Doleman, Ewan Roberts. Scr: John Roddick; based on A Million Dollar Story (1926). Dir: Gerard Glaister.

32. To Have and To Hold. Ray Barrett, Katharine Blake, Nigel Stock. Scr: John Sansom; from the short story “The Breaking Point” (1927) collected in Lieutenant Bones (1918). Dir: Herbert Wise.

33. The Rivals. Jack Gwillim, Erica Rogers, Brian Smith. Scr: John Roddick; based on the short story collection Elegant Edward (1928). Dir: Max Varnel.

34. Five To One. Lee Montague, Ingrid Hafner, John Thaw. Scr: Roger Marshall; based on The Thief in the Night (1928). Dir: Gordon Flemyng.

35. Accidental Death. John Carson, Jacqueline Ellis, Derrick Sherwin. Scr: Arthur La Bern; based on the novel Jack O’Judgment (1920). Dir: Geoffrey Nethercott.

36. Downfall. Maurice Denham, Nadja Regin, T.P. McKenna. Scr: Robert Stewart. Dir: John Moxey.

1964:

37. The Verdict. Cec Linder, Zena Marshall, Nigel Davenport. Scr: Arthur La Bern; based on The Big Four (1929). Dir: David Eady.

38. We Shall See. Maurice Kaufmann, Faith Brook, Alec Mango. Scr: Donal Giltinan; based on We Shall See! (1926; aka The Gaol Breaker). Dir: Quentin Lawrence.

39. Who Was Maddox?. Bernard Lee, Jack Watling, Suzanne Lloyd. Scr: Roger Marshall; based on the short story “The Undisclosed Client” (1926) collected in Forty-Eight Short Stories (1929). Dir: Geoffrey Nethercott.

40. Face of a Stranger. Jeremy Kemp, Bernard Archard, Rosemary Leach. Scr: John Sansom. Dir: John Moxey.

NOTES: Many sources say that there are 47 films in the series, including the Classic TV Archive. I have looked at the latter’s file and decided not to follow their lead because they combined two companies (Merton and Independent Artists). My list includes only those produced by Merton Park.

When the films in the British Edgar Wallace series were shown as part of a syndicated televised series in the US, the package was very likely boosted to 47 (or even more) with other, non-related titles. The EW title logo can be edited on to the opening of anything that looks similar (or fits the programme slot).

A good example is NBC’s Kraft Mystery Theatre (1961-63), where the first season (June-Sept, 1961) consisted of even more British B-movies re-edited for a one-hour TV slot. See this page for more details. One film I can remember (shown as a part of this group) is the non-mystery House of Mystery, which is actually a very effective, rather spooky supernatural/ghost story.

In the instance of the Merton Park-Edgar Wallace series, since 47 is often given as the number of films, I’ll use the Classic TV Archive list to describe the differences.

Independent Artists, set up by producer Julian Wintle, started in 1948; he was joined by Leslie Parkyn in 1958, locating the company at Beaconsfield Studios, England. Their only connection with Merton, apparently, was the distributor Anglo Amalgamated, who handled films for both companies. (Perhaps it was Anglo who made the sale of packages to US television?)

The Man in the Back Seat (1961), which was the subject of the original enquiry, was an IA film, distributed by Anglo (released in the UK in August 1961). British trade journal reviews (Kine Weekly, 15 June 1961; Daily Cinema, 21 June 1961), as well as Anglo�s original publicity releases, reveal nothing to suggest that this film had a Wallace connection/origin. Neither TV Archive nor I include it in the Merton EW series.

The Malpas Mystery (1960), listed by TV Archive in its list of IA films, was a Merton Park Studios-Langton production, according to the reviews in Monthly Film Bulletin [UK] (February 1961) and Variety (21 May 1969 for the US release). Kine Weekly (15 December 1960), however, confirms that it was indeed produced by Wintle & Parkyn at Beaconsfield Studios. It is, nevertheless, an EW entry.

Urge to Kill (1960) is included as an early Merton film by TV Archive, but, it seems, it was not produced as a part of their Edgar Wallace or Scotland Yard series, and I have excluded it.

There are seven other films cited by TV Archive which are all Merton productions (1963-1965) but, to all appearances, these are not related to any of their �series,’ including Scotland Yard and Scales of Justice.

Thus of the 47 films in the Classic TV Archive count, I add one (Malpas) and delete eight others. This takes the “Edgar Wallace” count to the 40 titles I have listed above.

Incidentally, Game for Three Losers (1965) — part of the TV Archive “seven” — was based on a novel by Edgar Lustgarten (screenplay by Roger Marshall; directed by Gerry O’Hara), but does not appear to be part of the Scales of Justice or any other series.

Sun 15 Feb 2009

— Following

my review of

Assignment Zoraya, by Edward S. Aarons, David Vineyard recently left this comment:

Aarons is another underappreciated writer who wrote clean uncluttered prose and knew his way around plot and character. The best of the Durell books are superior examples of their field and still hold up today even if the politics have left them behind.

I do have a question, though likely no one can answer it. The familiar portrait of Durell featured originally on the front covers and later on the back looked nothing at all like the lean black haired black eyed character known as the “Cajun” who I always pictured as a cross between Dale Robertson and Zachary Scott.

Gold Medal’s other series icons all looked a good deal like the characters within — Matt Helm, Joe Gall, Shell Scott, Travis McGee, Chester Drum, even Earl Drake’s “Man with No Face” — but Aaron’s “Cajun” was this blonde pale eyed guy in a fedora, and as late as 1962’s Assignment Karachi Durell is portrayed on the cover as a blonde.

I think the original portrait is by Barye Phillips who did most of the early Aarons covers and Karachi looks like it might be the work of Harry Bennett.

You would think in all the years the series ran and considering it always had steady sales that someone would have noticed the cover portrait was nothing like the character described in the book. Anyone know what was going on?

>>>>

Steve again. David and I have been batting this question around for a while, each providing the other with cover images. My problem with his question is that when I think of blond (or blonde), I think of Marilyn Monroe.

Obviously there are different shades of blond, including very light browns, but I think that there always has to be some yellow in it before hair can be considered blond. I just didn’t remember ever seeing Sam Durell with hair that fit what David was saying.

What’s more, when I came across one of the covers that David specifically referred to, Durell’s hair looked dark brown if not black, and nothing like blond to me. See above.

But David then supplied me with a closer look at the cover of Gold Medal GM k1505, which is not the 1962 printing above, but one that would have come out in 1964 or ’65 . See below:

It’s out of focus and lighter than the image I’d found, but yes, this time I saw what David was talking about. He’s not as blond as the lady standing next to him, but there are blond highlights in his light brown hair I hadn’t seen before. In any case, if the question was phrased as “Does Durell look like a dark-haired Cajun in this picture?” I’d have to agree that he does not.

I challenged David’s suggestion that the painting was done by Harry Bennett. I disagreed, seeing nothing of the latter’s stylized art in the cover, and suggested Ron Lesser instead. David agreed, saying “You are likely right about Lesser. As you said, Bennett usually signed his work. I thought of him because he did a lot of work for Fawcett and the background looked like his work.”

Here is the second cover that David sent me, one of the ones he believed was done by Barye Phillips:

I agree that Phillips is likely the artist. With the hat on the fellow whose face is at the top, though, it is difficult to determine what color is hair is, except that it is not black, more likely brown, and to me he looks more like an Irish pug than a dark-haired Cajun.

The one in the cover scene itself David calls “a fair-haired pale-eyed ‘Cajun’,” and he continues: “I’m curious if this was an editorial decision, an attempt to make him look more like Shell Scott, or just an artist’s interpretation that the editors and Aarons never bothered to correct. The novels describe Durrell as dark with black hair and eyes, a bit over six feet tall and lean, and resembling a Mississippi river boat gambler.”

To end the discussion between David and me, but to open it up to others to jump in if they wish, here’s a cover, probably published in the late 1970s or even the 80s, in which Durell, to me, finally looks something like the author, Edward S. Aarons, might actually had in mind:

The cover was obviously done by Robert McGinnis, but whether he did the small insert close-up of Sam Durell, I’m not sure. I’d need a closer look to be positive. Whoever it was, I think he finally got it right.

Here’s David again. It’s his question, and he deserves the last word:

“No doubt you are right about the question not getting answered, I just thought I would put it out there and hope one of the Gold Medal experts might have an idea. I can’t think of another series where the covers consistently went out of their way to portray the character as looking almost completely different than the one described in the book.”

Sun 15 Feb 2009

NOTE: This is the third in a series of three reviews of Durango Kid movies from the 1940s. The previous two were

Phantom Valley (1948) and

Whirlwind Raiders (1948).

THE BLAZING TRAIL. Columbia, 1949. Charles Starrett, Smiley Burnette, Marjorie Stapp, Fred Sears, Jock Mahoney, Trevor Bardette, Hank Penny, Slim Duncan. Screenplay: Barry Shipman. Director: Ray Nazarro.

You’ve probably anticipated me by now, but there’s no trail to be blazed (or on fire) in this one either, still another Durango Kid movie.

But like Phantom Valley, the earlier entry also directed by Ray Nazarro, this one’s also a decent mystery puzzler, complete with voiceover narration by Charles Starrett.

At issue here, after the shooting death of old Mike Brady, is the matter of his will, which leaves the bulk of his estate to the “wrong” one of his two surviving younger brothers. The will was signed and witnessed (but not read) and sealed securely. How was the document altered? If it was, of course.

As the dead man’s attorney, Luke Masters (Fred Sears) vouches for it, and while his daughter Janet (Marjorie Stapp) acts rather suspiciously about it, especially in the beginning, so does she. (See the photo to the right to get a good look at both Sears and Ms. Stapp.)

Smiley Burnette runs a one-man newspaper in this one. He’s both the reporter for the Bradytown Bugle and the editor and the publisher, which makes for very funny problems as he tries to manipulate the movable type and generally get his printing press running. (He has no capital “D,” which makes it hard to spell Durango in the headlines.)

The two brothers are obvious suspects, and so are the local gambler “Full House Patterson” (Jock Mahoney, who later of course became TV’s “Range Rider” as Jack Mahoney, not to mention a couple of Tarzan movies) and Brady’s long-time foreman, Jess Williams (Trevor Bardette, who according to IMDB, made 228 movie and TV appearances, many of them in crime or western roles just like this one).

Steve’s last name in this one is Allen, and yes, I know. While the immediate investigation is clumsily done – how smooth could things go with Smiley involved? – the secret of how the will got altered is an impossible crime that’s worth double the price of admission. (Easily. What did it cost to go to the movies in 1949? For someone my age at the time, no more than 10 or 12 cents.)

And while I know you are probably not wondering, there’s no romantic interest at all. The songs are pretty good, though.

PostScript: I was just thinking. If you took these three movies and worked out just how much screen time Starrett got versus how much Smiley Burnette did, I have a feeling that… Have you ever watched one? What do you think?

— October 2004.

Sat 14 Feb 2009

PulpFest press release copy:

Edgar Award-winning writer, editor, and publisher Otto Penzler has been chosen to be the Guest of Honor at this year’s PulpFest, a convention for collectors and devotees of vintage pulp fiction, which will be held July 31 through August 2 at the Ramada Plaza Hotel and Convention Center in Columbus, Ohio.

PulpFest not only attracts book dealers and collectors from all across the country but also hosts seminars on various aspects of pulp history and stages auctions of rare and desirable material including vintage hardcovers, paperbacks, and dime novels in addition to the fabled woodpulp magazines from which the convention takes its name.

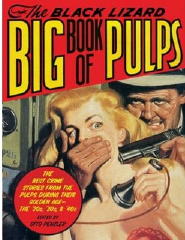

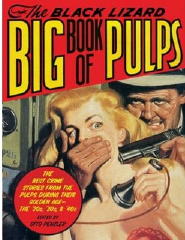

Penzler, whose recent anthology The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps has done more to renew interest in Golden Age pulp fiction than any mainstream publication in recent history, is a perfect Guest of Honor in that he is also a world-class collector of crime fiction, many of whose most notable authors—including Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Cornell Woolrich, Erle Stanley Gardner, and John D. MacDonald—toiled in the pulp vineyards before achieving mainstream success with major publishers.

Penzler will regale PulpFest attendees with stories of his adventures in the publishing business and as a lifelong collector. He is expected to give attendees a preview of his much anticipated Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories, an upcoming anthology collecting rare yarns from the prestigious pulp magazine that was home to Hammett, Chandler, and other giants of hard-boiled detective fiction.

Still the proprietor of The Mysterious Bookshop, a New York City landmark that celebrated its 30th anniversary last year, Otto Penzler published The Armchair Detective, an Edgar-winning quarterly journal devoted to the study of mystery and suspense fiction, for seventeen years. He was the founder of The Mysterious Press, now an imprint at Grand Central Publishing, and also launched the publishing firms of Otto Penzler Books and The Armchair Detective Library.

He currently has imprints at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in the United States and Quercus in the U.K. In 1977, he won an Edgar Award for the Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection. The Mystery Writers of America gave him the prestigious Ellery Queen Award in 1994 for his exceptional contributions to the publishing field. He was also honored with MWA’s highest non-writing award, the Raven, in 2003.

Penzler first endeared himself to pulp-fiction fans in the late 1970s by publishing a two-volume collection of short stories featuring Norgil, a magician-detective created by Walter B. Gibson, who also wrote more than 280 novel-length adventures of pulpdom’s legendary crime fighter, The Shadow. In 1984, Penzler reprinted two of that character’s best-remembered adventures in The Shadow and the Golden Master.

Subsequently his Mysterious Press issued trade-paperback anthologies of classic pulp detective stories by Carroll John Daly, Erle Stanley Gardner, Frederick Nebel, and Norbert Davis. First You Dream, Then You Die, a deluxe hardcover biography of veteran pulp scribe Cornell Woolrich published by The Mysterious Press in 1988, earned an Edgar for author Francis M. Nevins and became a standard reference work.

In addition to having access to interviews and seminars featuring Penzler and other guests, PulpFest attendees can shop for vintage paper collectibles in the convention’s spacious Dealers’ Room, in which dozens of merchants will exhibit their wares. Tens of thousands of pulps will be available for purchase, along with various books and magazines of related interest. Publishers of facsimile pulp reprints will also be on hand to supply fans with inexpensive but high-quality alternatives to the original rough-paper periodicals.

For additional information and downloadable registration forms, interested parties are encouraged to visit the convention’s web site, www.pulpfest.com, which will be updated regularly in the weeks and months to come.

Sat 14 Feb 2009

In my

review of the Durango Kid movie,

Whirlwind Raiders (1948), the basis of which was the existence of the Texas State Police which temporarily replaced the Texas Rangers as a law enforcement movie in that state after the Civil War. According to the movie, the State Police were “a bunch of crooks with political connections who rode sway over the populace with grafts, holdups and penny ante corruption throughout their ranks.”

My question was, how true was all of this? Walker Martin replied first, agreeing that the allegations against the Texas State Police were all pretty much true. In a followup comment, David Vineyard agreed, and expanded on this extensively, saying —

The problem with the Texas State Police was two fold. First they were imposed in place of the Rangers by the Federal government after the Civil War, and second they were highly politicized with positions of authority being sold to the highest bidder, who in Reconstruction Texas were likely to be carpetbaggers and crooks — the only people with any money.

They would have been resented even if they had done a good job, but by any standard they accomplished nothing and the state had descended into such a chaotic condition under them that even the Army wanted them disbanded and the Rangers reformed.

They managed to hold on until 1876 when the Rangers were reformed in response to wide spread outlawry and the renewed threat of the Comanche and Apache in western Texas.

Anyone wanting to know more should read Walter Prescott Webb’s The Texas Rangers which is an epic Pulitzer Prize winning history of the organization from it’s origins in the Austin colony to 1936.

It was also loosely the basis of the movie The Texas Rangers (1936), directed by King Vidor with Fred MacMurray and Lloyd Nolan, remade as The Streets of Laredo (1949) with William Holden and William Bendix.

The sequel, The Texas Rangers Ride Again (1940) was a B film, but had a screenplay by Black Mask alum Horace McCoy, and reflected the stories he did of modern Ranger Jerry Frost in the Mask.

The Rangers were hardly pristine, but because the organization was always small and depended on the authority of one man with a badge and a gun it seldom had the bureaucracy to be as corrupt as the Texas State Police.

Even today there is some confusion that the Texas Highway Patrol and the Rangers are the same. They aren’t. The Rangers are a separate investigative unit within the state police who aid in state wide crime enforcement and are called in by small towns and counties when needed.

For most of the 20th century there have seldom been more than 500 Rangers who are recruited from the police forces around the state. Like the FBI they provide CSI and other support for localities who can’t afford their own labs and investigators. Contrary to their reputation for gunplay they actually have a good record of negotiating peaceful endings to bad situations and most agree if the FBI and ATF had left Waco to the Rangers they could have ended it peacefully.

It isn’t that they haven’t had their bad times. In the 1920’s when Pa and Ma Ferguson controlled the governors office the Klan got a toe hold in the Rangers. A new administration brought in the legendary Colonel Homer Garrison who cleaned the Rangers up and turned them into a modern police unit.

Garrison was so successful that during WWII he was chosen by FDR and Winston Churchill to reform the police in former Nazi controlled territories in North Africa, and helped to reform the French and German police when the war ended. Supposedly Stalin invited him to Russia to help reform the Russian police but he politely declined.

That said the Rangers again had some trouble during the sixties during the race troubles, but again reformed and cleaned up their act. Notably even during this period it was a single Ranger who ended boss rule in South Texas when he brought down the infamous Duval County Bosses ending the virtual slavery of itinerant workers in that part of the state.

Another film to see tackle the Texas State Police is Galloping Legion, a better than usual Bill Elliot western with Jack Holt. Not an A perhaps, but a B+ certainly.

The Rangers, like Scotland Yard and the RCMP, trade on their legend for part of their effectiveness, but like those organizations have been aided by legendary members from Deaf (Deef) Smith and Big Foot Wallace, Rip Ford, McNelly, Lee Nace (yes, that’s where Lester Dent got the name — Nace was the Ranger who befriended William Henry Porter, O Henry when he was arrested and who is the model for the sympathetic Ranger Captain in the story that introduced the Cisco Kid), and Red Burton who arrested John Wesley Hardin and once put down a riot single handedly inspiring the “one riot one Ranger” saying (not the motto of the organization — that’s “Know you are right, then go ahead”) enshrined on the statue of Ranger Lobo Gonzales that stood in the lobby of Dallas Love Field.

Other noted Ranger’s included the aforementioned Lobo Gonzales who cleaned up the oil boom town of Kilgore in one afternoon and Frank Hamer who hunted down Bonnie and Clyde. And I’ll confess aside from being a little prejudiced as a Texan, I’m the great grandson of a Ranger, so take all this with a grain of salt and do your own research.

While they have their low points the actual unvarnished history of the Rangers reads like a novel. Even today a single Ranger carries with him the authority of the entire state. They aren’t infallible, and there are black marks in their history, but for once much of the hype is based on fact instead of public relations.

Sat 14 Feb 2009

David Vineyard left this comment to a

short piece written by Ed Hulse about Charles Starrett, star of the Durango Kid movies, but since I’m in the process of reviewing some of the Durango movies, myself, it seems like an appropriate time to re-post it here:

“My first exposure to Charles Starret wasn’t in a western at all. He is the young leading man in the excellent Mask of Fu Manchu with Boris Karloff and Myrna Loy as the evil doctor and his daughter, Lewis Stone as Nayland Smith, Karen Morley as the romantic interest, and Jean Hersholt.

“It was only later that I saw the Durango Kid films. They still show up once in a while on the Encore Western channel, and the comic book based on them had a long run — though they can be pricey since Frank Frazetta’s White Indian was the backup feature.”

And as long as we’re talking western movies, David left the following comment after

my review of

Mackenna’s Gold (1969), a rousing western adventure starring Gregory Peck and a host of other well-known actors, not all of whom are well-known for being in westerns:

“Mackenna’s Gold, based on a terrific book by Will Henry (aka Clay Fisher and also Heck Allen who wrote cartoons for MGM during the Tex Avery era) is a big shaggy likable movie. It never really comes together, but there is so much going on and everyone is trying so hard that you feel like giving it a pass when it misfires.

“There are some high points, including Edward G. Robinson as Old Adams of the Lost Adams Mine, and Julie Newmar as the most statuesque Apache in history. For the most part the movie sticks to the book, save at the end which is unfortunate. There are some fair special effects (for the time, they are pretty obvious now), and nice set pieces.

“The real problem is that Omar Sharif is such a charming rogue that they couldn’t kill him off so the film gets a little distracted toward the end. Those that have read Will Henry’s novel will understand that the climax of the film is a bit of a disappointment, though it does manage some elements of the original. Victor Jory’s narration is great.

“Two other caveats, Jose Feliciano crooning “Old Turkey Buzzard” will drive you to distraction, and a fine cast including Lee J. Cobb, Burgess Meredith, Anthony Quayle, Eli Wallach, Eduardo Cianelli, and Raymond Massey are largely wasted. On the other hand Keenan Wynn has fun chewing scenery as Sharif’s Mexican bandit crony, and Ted Cassidy is menacing as a giant mute Apache and there is a hint Rudy Soble might have been able to do something with a noble Apache, but doesn’t get the chance.

“One correction, Telly Savalas doesn’t play a cavalry officer, but a treacherous sergeant who betrays his men for a shot at Adams Gold. Those who know their western history will know that the Lost Adams Mine is a real life treasure that modern adventurers are still looking for. In many ways Mackenna’s Gold is less a modern Treasure of Sierra Madre than a precursor of Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

Thu 12 Feb 2009

WHIRLWIND RAIDERS. Columbia, 1948. Charles Starrett, Smiley Burnette, Fred Sears, Philip Morris, Jack Ingram, Nancy Saunders, Patrick Hurst, Don Kay Reynolds (as Little Brown Jug), Doye O’Dell and The Radio Rangers. Screenplay: Norman Hall. Director: Vernon Keays.

WHIRLWIND RAIDERS. Columbia, 1948. Charles Starrett, Smiley Burnette, Fred Sears, Philip Morris, Jack Ingram, Nancy Saunders, Patrick Hurst, Don Kay Reynolds (as Little Brown Jug), Doye O’Dell and The Radio Rangers. Screenplay: Norman Hall. Director: Vernon Keays.

Well, once again there are no raiders in this next Durango Kid movie, or if there are, by no connotation of the word, are they “whirlwind raiders.” The bad guys are more insidious than that. At a time when the Texas Rangers were officially disbanded, the “Texas State Police” were put in charge, and if the screenwriter for this film is to be believed, they were a bunch of crooks with political connections who rode sway over the populace with grafts, holdups and penny ante corruption throughout their ranks.

(If anyone knows how true this small aberration in Texas history might be, let me know.)

Charles Starrett is Steve Lanning in this one, a former Texas Ranger working undercover to root out the bad guys, led by saloon owner Tracey Beaumont (Fred Sears) and his head henchman, Buff Tyson (Jack Ingram, whom I am sure always played a crook in his 271 film appearances, or in at least most of them).

But what this means is that in this movie, as opposed to the previous one, Lanning does have of a reason for having two identities. Whenever he does anything of semi-illegality, such as breaking into Beaumont’s safe late at night, he does it as the Durango Kid.

I mentioned earlier my (adult-based) puzzlement that no one ever seems able to recognize Steve as Durango, but in this movie, a young lad named Tommy Ross (played by Little Brown Jug, as he is billed in the credits) actually does discover that the two are indeed one and the same.

He is quickly sworn to secrecy and sworn in as an adjunct Texas Ranger to boot. His first assignment? To follow the actions of Smiley Burnette, who “is acting very suspiciously.”

Smiley in this movie is a traveling tinkerer who’s set up shop in the same town, and with a covered wagon filled with pots and pans and objects of other obviously beneficial value, including a cage containing two chickens, it establishes a very convenient venue for Smiley to clown around in, making an enormous racket most of the time he’s on the screen.

There’s no love interest in this one either, or just the smallest of hints that newspaper owner Bill Webster (Patrick Hurst) is interested in making moves on Claire Ross (Nancy Saunders), daughter of rancher Homer Ross (Philip Morris). There’s no time to add any mushy stuff to this story, which is chuck full of action, comedy and singing, in just about that order.

Additional comments: This was the only movie Patrick Hurst made, and he plays his role so thinly in this one, you might not even realize he was in it. Philip Morris, although only 55, looks old and tired, and it’s scary to learn that he died the very next year. Beginning in 1949, Fred Sears began his career as a director with yet another Durango movie, Desert Vigilante. He did lots of westerns among his 51 films, including the 1958 version of Utah Blaine, based on the novel by Louis L’Amour.

— October 2004.

[UPDATE] 02-12-09. This is the second of three Durango Kid movies I taped and watched over four years ago now. I’ll post the third review tomorrow, if all goes well.

After digging the reviews out of storage, it prompted me to sign up for the Encore grouping of premium cable channels yesterday — one of them being, of course, the Western Channel, the source of these Durango films.

I canceled today without taping a single one of their offerings. I do not care to pay a premium fee for cable channels with huge logos (bugs) in the lower corner of the screens. These must have appeared between now and the last time I’d signed up for the Encore channels, since they weren’t there before, at least not as permanently and as ugly as they are now.

Turner Classic movies uses logos, but they come on only every 30 minutes or so, and then quietly disappear. The Encore logos are four times the size and are opaque white. Maybe I’m the only one who hates these things. And don’t get me started on network TV and the bulk of the non-premium cable channels. Besides news and sports, I don’t watch any of them.

Not only do they have logos, but they have characters from next show come wandering in on the bottom of screen and jump around until you notice them (as if) and then whoosh off, sound effects included, all the while the current show is still on. Besides this sort of nonsense, and five-minute blocks of commercials, I can’t see anyone except invalids and shut-in’s putting up with this. But I guess they do.

On a more pleasant note, I’m going to repeat one of the comments that Walker Martin left after I posted yesterday’s Durango Kid feature:

“Today, I just received a new book, Western Film Series of the Sound Era, by Michael R. Pitts. Published by McFarland it’s 474 pages [long and covers] 30 western film series from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s. Included is a long chapter on The Durango Kid, 45 pages discussing all the films and 11 photos and posters. Also there is a chapter on the Dr. Monroe series discussing the three films starring Charles Starrett.

“McFarland Books website lists the 30 series covered.”

It’s just out. It was published only last December, and I’ve ordered a copy myself. As Walker says, the various series it covers are listed on the McFarland website, but to save you the time of searching online for it yourself, here’s the Contents Page:

BILLY CARSON 3

BILLY THE KID 21

CHEYENNE HARRY

THE CISCO KID 43

DR. MONROE 64

THE DURANGO KID 68

FRONTIER MARSHALS 113

HOPALONG CASSIDY 118

THE IRISH COWBOYS 175

JOHN PAUL REVERE 180

LIGHTNING BILL CARSON 183

THE LONE RANGER 190

THE LONE RIDER 208

NEVADA JACK MCKENZIE 219

THE RANGE BUSTERS 232

RANGER BOB ALLEN 254

RED RYDER 259

RENFREW OF THE ROYAL MOUNTED 284

THE ROUGH RIDERS 290

ROUGH RIDIN’ KIDS 300

ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE 303

THE SINGING COWGIRL 320

THE TEXAS RANGERS 322

THE THREE MESQUITEERS 340

THE TRAIL BLAZERS 384

WILD BILL ELLIOTT 391

WILD BILL HICKOK 399

WILD BILL SAUNDERS 412

WINNETOU 415

ZORRO 429

Wed 11 Feb 2009

PHANTOM VALLEY. Columbia, 1948. Charles Starrett, Smiley Burnette, Virginia Hunter, Joel Friedkin, Robert Filmer, Teddy Infuhr, Ozie Waters & The Colorado Rangers. Screenwriter: J. Benton Cheney. Director: Ray Nazarro.

Strangely enough, there are no phantoms in Phantom Valley. But someone definitely seems determined to start a range war between the cattlemen and the local homesteaders. The mystery is who this crooked mastermind is, and it’s up to Steve [Collins] and his alter ego, The Durango Kid, to find out who.

Assisting him is Smiley “Sherlock Holmes” Burnette, whose expertise, gained from a correspondence school manual (and a large magnifying glass), proves to be less than very valuable. Assisting Smiley, and his nemesis who easily outwits him at every turn, is a young apple-eating lad (Teddy Infuhr) who collects the clues that Smiley simply tosses away.

When I was a kid, the Durango Kid movies were the best there were. Roy was OK, I don’t remember Hoppy at the time, and Gene, Rex and Monte were all good but second-rate. But while I was watching this one now, I started to wonder about things that never occurred to me at the time.

Things such as, why did Steve (see below) bother even having a secret identity? It was — and still is — neat that he had a cave where he kept his white horse and DK outfit, but what good purpose did it serve in changing to and becoming the Durango Kid? (This is heresy, I know. My younger self would hardly believe my ears, hearing me say such things.)

But how come no one recognized him, with only a black bandanna over the lower portion of his face? How come the bad guys shoot so badly and, truth be told, how come they always start shooting too soon?

What was really neat (to me at the time) was that in almost all of the Durango Kid movie, Starrett’s character was always named Steve. Steve Langtry, Steve Norris, Steve Warren, Steve Blake. Two references on Phantom Valley disagree on which Steve it was that Starrett played in this film. One says Collins, the other doesn’t say one way or the other. After watching it, I don’t believe he ever had a last name.

There is a girl in this one — Virginia Hunter as Yancey Littlejohn — but she’s not really a mushy romantic love interest as she would have been in one of Gene’s or Roy’s movies. She’s the daughter of an elderly and slightly crippled attorney new to Phantom Valley — Joel Friedkin as Sam Littlejohn — and along with a banker named Reynolds (Robert Filmer) her father becomes one of the primary suspects, and Yancey is his primary defender.

And what do you know? This is an honest to goodness detective puzzler. It surprised me, but minor as it is — hidden between the songs and Smiley’s foolish antics — there it is, and it’s good in its fashion as — dare I say it? — some of the Charlie Chan movies of the same vintage.

Additional comments: Teddy Infuhr you might remember as the mute boy in Sherlock Holmes and the Spider Woman (1944) and (you might not) several times over as one of the many kids in the Ma & Pa Kettle series of comedy films.

Virginia Hunter is very pretty and attractive, but she seems to have had only a short career in films. Her roles include at least one other Durango movie, several Three Stooges shorts, and a small part in the noir thriller He Walked by Night (1948). Mostly B-movies, looking down through the rest of the list, and often small uncredited parts at that, but she makes the most of this one.

« Previous Page — Next Page »

WHIRLWIND RAIDERS. Columbia, 1948. Charles Starrett, Smiley Burnette, Fred Sears, Philip Morris, Jack Ingram, Nancy Saunders, Patrick Hurst, Don Kay Reynolds (as Little Brown Jug), Doye O’Dell and The Radio Rangers. Screenplay: Norman Hall. Director: Vernon Keays.

WHIRLWIND RAIDERS. Columbia, 1948. Charles Starrett, Smiley Burnette, Fred Sears, Philip Morris, Jack Ingram, Nancy Saunders, Patrick Hurst, Don Kay Reynolds (as Little Brown Jug), Doye O’Dell and The Radio Rangers. Screenplay: Norman Hall. Director: Vernon Keays.