February 2009

Monthly Archive

Tue 3 Feb 2009

Posted by Steve under

GeneralNo Comments

A review of a Murder, She Wrote book I posted last Friday also included a bibliography of all the other novels based on the series. This has produced a large number of follow-up comments, many of them on the definition of what the term novelization actually means. (As opposed, say, to the longer, more cumbersome phrase “Original novel based on characters created for a televison series.” )

If this sounds like an exciting topic to you — and it is to me! — you might want to go back and read through the discussion so far. See https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=995.

— Steve

Mon 2 Feb 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

HAL WHITE – The Mysteries of Reverend Dean. Lighthouse Christian Publishing; trade paperback; story collection; 2008.

There is a long and illustrious list of clerical detectives in mystery fiction. The first one to come to mind is usually G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown; indeed, like Brown, most of the memorable clerical sleuths have been British.

In America there have been fewer men (and women) of the cloth who involve themselves in criminal investigations: Melville Davisson Post’s Uncle Abner is the outstanding example of one who did on this side of the Pond.

On occasion Abner would tackle what is commonly called today “impossible crime” (or, more specifically, “locked-room”) problems of the kind that sometimes bedeviled Father Brown. Neither Brown nor Abner, however, spent more than a fraction of their time on such conundrums.

But now we come to one clerical sleuth who EXCLUSIVELY devotes his time to solving locked-room crimes: Hal White’s Reverend Dean. This clergyman never actively seeks out such perplexing problems; his principal concern is always in saving souls. Yet somehow Reverend Dean becomes embroiled in these things with amazing regularity.

Patience is counted as a Christian virtue, and the reverend has it in abundance; indeed, without patience he couldn’t solve any of the problems with which he is confronted.

Strictly speaking, intelligence may not be exclusively another Christian virtue, but Dean also has it in abundance: You wouldn’t know it to look at him, but this modest, self-effacing man’s “little grey cells” are constantly working ratiocinative miracles inside his skull.

Take, for instance, how he solves the conundrum of a woman stabbed to death in a room with locked windows, a triply-locked door, protected by a guard dog, and under observation by three witnesses.

Or consider the woman who, if the evidence is to be believed, can walk through solid walls and shoot at someone while suspended in space. Or how about … but you should really read The Mysteries of Reverend Dean yourself.

You won’t be disappointed.

______

A website devoted to other clerical detectives is at:

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/philipg/detectives/contents.html

Hal White’s webpage, which focuses on his book ‘The Mysteries of Reverend Dean’ and other locked-room mystery anthologies, can be found at:

www.halwhitebooks.com

Mon 2 Feb 2009

Reviewed by MIKE GROST:

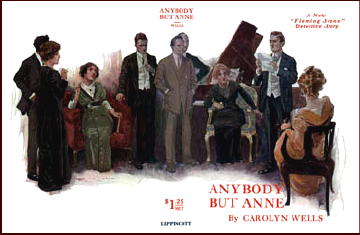

CAROLYN WELLS – Anybody But Anne. J. B. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1914.

Anybody But Anne shares most of the characteristics of Wells’ later Faulkner’s Folly (reviewed here not too long ago):

● It is a full, formal mystery novel, of the kind that would later be popular in the Golden Age.

● It is set in a country house, and anticipates the mysteries soon to be popular in such houses.

● The cast of suspects resemble those to be found in many later detective books.

● It is a locked room mystery — but the solution of the locked room is based on ideas that would later be regarded as cheating. Still, the cheat of a solution shows some real ingenuity.

● The book shows the imagination with architecture, that would later be part of the Golden Age. It comes complete with a floor plan. The country house is of the kind that might have later inspired the mystery game known as Clue or Cluedo: there is even a billiard room!

● Wells pleasantly includes some subsidiary mysteries, that have nothing to do with the locked room. These too show some mild but pleasing ingenuity. Such subplots are also standard in Golden Age detective novels.

I do not know if Wells invented the above template for formal mystery novels, or whether she derived it from other authors. Anybody But Anne does establish, that what we think of as a “typical Golden Age style mystery novel,” was in existence before what is often thought of as the official start of the Golden Age in 1920. It is also a fact, that Wells was American, and that her book is set in the United States: somewhere in New England.

The best parts of Anybody But Anne have charm. People looking to sample Wells, might enjoy this novel, or at least its best chapters. It is at its best in the opening (Chapters 1-6), which sets up the architecture, characters and murder mystery; two later chapters that tell us more about the house as well as exploring some subsidiary mysteries (14, 17), and lastly the solution (Chapters 18, 20). Together these sections make a readable novella. The novel has been scanned by Google Books, and can be read free on-line.

We get a good portrait of Wells’ sleuth, Fleming Stone, in action in these sections. Oddly, he is missing in most of the middle of the book, sections which generally are not that interesting anyway. Like most pre-1945 detectives, he is more characterized by his skills and behavior as a detective, than by any knowledge we get of his personal life.

Stone has a penetrating intellect, that goes right to the heart of clues to the mystery, in the evidence at hand. He is crisp and business-like at delivering his insights, sharing his ideas immediately with the other characters and the reader.

We do learn that Fleming Stone is outside of the world of romance, like many other early detectives. Wells gives an interesting psychological portrait of this.

Mon 2 Feb 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by George Kelley & Marcia Muller:

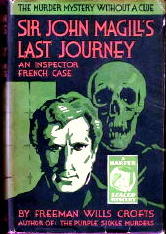

FREEMAN WILLS CROFTS – The Loss of the “Jane Vosper.”

Collins, UK, hardcover, 1936. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1936. Many reprint editions, both hardcover and soft, including: Collins, UK, hc, 1980 [Crime Club 50th Anniversary edition] and Grosset, US, n.d (both shown).

Crofts was a transportation engineer and worked for railway companies for many years before retiring in 1929 to become a full-time writer.

A number of his novels make use of his technical knowledge of railroading and shipping, such as Death of a Train (1947), in which Inspector French investigates a World War II plot to divert vital supplies being shipped to the British forces in North Africa. Similarly, The Loss of the “Jane Vosper” draws on Crofts’s knowledge of the shipping industry.

On a dark night in the mid-Atlantic, the cargo ship Jane Vosper is rocked by explosion after explosion. Soon afterward, the ship sinks. An insurance investigation is launched, and it soon becomes apparent that the sinking of the ship was no accident.

Inspector French enters the case and begins to piece details together-including particulars of what cargo the ship was carrying. A cargo swindle is revealed-one that leads to murder. French works with precision, ever conscious that unnecessary delay may lead to additional killings.

The background detail in this novel is particularly good, and French is in top form, always playing fair with the reader and making us privy to his private thoughts. French is likable, a pleasant, unassuming man with none of the sometimes unfortunate affectations of other popular classic sleuths.

This book — and most of Crofts’ others — presents no real challenge to the reader in terms of outwitting the detective and solving the case first. If anything, we feel that we are being taken by the hand and led on a genteel journey through the routine of a careful and dedicated investigator.

Other Crofts novels dealing with the shipping industry include Mystery in the English Channel (1931), Crime on the Solent (1934), Man Overboard (1936), and Enemy Unseen (1945).

Books in which Crofts drew on his railroading background include Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930), Wilful and Premeditated (1934), and Dark Journey (1954). A short-story collection featuring Inspector French, Many a Slip, was published in 1955.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 1 Feb 2009

Hi Steve,

I wonder if you can help me. I need to get hold of an obituary for novelist and screenwriter Roy Chanslor who died in September 1964. It seems the only one appeared in an issue of Variety sometime that fall. I don’t know if you know anyone who might be able to help, or if you could ‘advertise’ on your blog. I would be most grateful if you could. Variety does have a sort of archive, but it’s only for old film reviews,

Bibliographic data [crime fiction only]:

CHANSLOR, ROY. 1899-1964.

Lowdown. Farrar & Rinehart, hc, 1931.

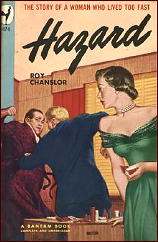

Hazard. Simon & Schuster, hc, 1947; Bantam #474, pb, 1949. Film: Paramount, 1948 (scw: Arthur Sheekman, Roy Chanslor; dir: George Marshall).

[Expanded from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

Chanslor also has a long list of writing credits on IMDB, including Tarzan Triumphs, The House of Fear, Black Angel and Cat Ballou.

Bill Crider had an interesting post about him last year on his blog. Follow the link.

More? His wife, Torrey Chanslor, was both a well-known illustrator of children’s books and a two-time mystery writer. Where or when she died is apparently unknown, but her two detective novels have recently been reprinted by Rue Morgue Press. Follow this second link for a long biographical essay about her.

CHANSLOR, (Marjorie) TORREY (Hood). 1899-?

Our First Murder (Stokes, 1940, hc) [Lutie and Amanda Beagle; New York City, NY]

Our Second Murder (Stokes, 1941, hc) [Lutie and Amanda Beagle; New York City, NY]

Sun 1 Feb 2009

The following observation and question was first posted here by Vince Keenan on June 4, 2007:

“I recently reread Westlake’s

The Hot Rock for the first time in ages and was struck by the fact that Grofield makes an appearance. One of the members of Dortmunder’s crew, Alan Greenwood, is forced to change his last name after he’s arrested. We learn in the book’s penultimate chapter that he’s now Alan Grofield.

“Grofield had already been established in the Parker series as well as his own books at this point. So is this a belated origin story, as they say in the comics field?”

I didn’t know, but I more or less assumed that Vince was right. No one responded to this online inquiry to say for sure, until today, when I heard from Gabe Lee, who left the following comment:

“I remember seeing similarites in Greenwood and Grofield while reading

The Hot Rock the first time a few years ago, having recently devoured all of the Stark books in order.

“I felt vindicated at the end when they were revealed to be the same person.”

When I thanked Gabe for leaving a definitive answer at last, he replied:

“A bit more I didn’t see mentioned here…

The Hot Rock was started as a Parker novel by Stark. The premise got too absurd for Parker’s character; no way he would have put up with that nonsense.

“Westlake rewrote the book and created Dortmunder to replace Parker as the main character. I’m assuming Grofield was in before the rewrite, and was changed to Greenwood (same initials, same first name spelled differently). He then switched Greenwood back to Grofield as Vince noted earlier.

“It creates a fun chicken and egg scenario; maybe Grofield came first and that name was still clean. It’s one of the fun crossover tricks to look out for among Westlake’s many pseudonyms.

“Another fun thing to look for, he often uses ‘Pointers’ and ‘Setters’ for restroom signs in bars, and uses it under different author names. I’ve seen other (non-Westlake) authors use it as well, but can’t recall where. I’m guessing it’s sort of an inside joke among the writers, or an homage, but don’t know where it started.”

To which I responded by saying: I think that researchers with graduate theses and dissertations in mind will have a field day with all of the in-jokes and cross-references in Westlake’s work. If Westlake had been a “literary” figure instead of a mere mystery writer, I’d be sure of it.

Then to Gabe, for the final word:

“I completely agree, the crossover stuff is fun to look for. There’s so much of it, and I can picture the late great Mr. Westlake chuckling as he typed away. BTW, after racking my brain a bit I think Charles Willeford uses the Pointers and Setters thing in Cockfighter from 1962… I’ll have to re-read it to be sure.”

Sun 1 Feb 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors[6] Comments

Two comments following my

review of

The Saint in Trouble, by Leslie Charteris, should be of interest. — Steve

(1) David L. Vineyard —

As far as I know, the only Saint novel to contain original Charteris material after about 1960 was Salvage for the Saint, and that only because it was based on stories Charteris wrote for the long running Saint comic strip drawn by Mike Roy and later John Spanger and Doug Wildey (TV’s Jonny Quest). I’ve read that he also wrote original stories for the Saint comic book too, but all the ones I’ve seen were reprints of the comic strip.

Towards the end of the run of The Saint television series and the Saint Mystery Magazine Charteris authorized novelizations of the series and several were run in the magazine and later reprinted in hardcovers and paperback.

None of them really capture the Saint or Charteris, though the best is probably Vendetta for the Saint by veteran American sf writer Harry Harrison (author of Make Room Make Room, the basis for Soylent Green, and the Flash Gordon comic strip), based on a two part episode of the series and released as a movie.

I don’t know how many of these were done, but they did continue into the Ian Oglivy Return of the Saint series.

(2) Ian Dickerson —

The last Saint book solely by Charteris was the 1963 short story collection The Saint in the Sun, making the last Saint novel solely by Charteris the 1946 story The Saint Sees It Through.

Some of the latterday collaborations do indeed read like novelisations, but some of them read quite close to original Charteris. Charteris was never shy about crediting his collaborators –- except Harry Harrison because he didn’t want his name on the book –- and always edited the manuscripts before they went to print.

Salvage for the Saint was not based on a comic strip story, it was in fact based on the two part Ian Ogilvy episode entitled “Collision Course.”

“The Red Sabbath” [mentioned by Steve as having unknown antecedents] was based on the Ogilvy episode “One Black September.”

EDITORIAL COMMENT: For a long online biographical appreciation of Leslie Charteris by Ian, complete with several photos, follow this link.

« Previous Page