March 2009

Monthly Archive

Mon 2 Mar 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors[3] Comments

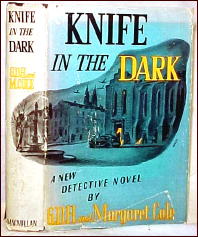

If you’ve been watching this blog constantly over the past few days, you will have noticed that one book has received two separate reviews, that being Knife in the Dark, by G. D. H. and Margaret Cole. David Vineyard left the following comment after the first of these, that being the one that I wrote. Of note, of course, is that he doesn’t spend all of his time talking about the Coles. — Steve

While I never read any of the Mrs. Warrender stories I did read several of the Supt. Wilson ones, and eventually had to grant the chief criticism of the Coles put forward by Haycraft and others, that the Coles put together a fair puzzle but they were awfully dull. I’ll check out some of the Warrender tales and see if that still holds. Someone once said of Daniel DeFoe that he “employed dullness brilliantly” but that’s hardly a virtue in a detective story.

The Coles were hardly alone in the category of being dull reads. I enjoy many of Freeman Wills Crofts’ books and those of John Rhode, but though both could get some action going, both could be pretty dull too. There’s a certain charm the first time you encounter one of Crofts’ timetables, but it grows thin fairly soon, and some of Rhode’s later Dr. Priestley books could be used to cure insomnia.

One of the problems with the classical tec tale is it sometimes got so involved with the puzzle and the rules it forgot the rule about entertaining.

The absurd length that this was taken to was in the Dennis Wheatley books, which presented you with characters, motive, even clues like cigarette butts, but you had to play the detective. Alas they pointed out the problem that murder wasn’t much fun without a good detective and things like a plot and real story. They might be fun for a party game but they weren’t much to curl up before the fire with.

One of the reasons we still read Christie, Marsh, Sayers, and Allingham when so many others have gone the way of the dodo is that they weren’t afraid of a little melodrama, adventure, intrigue, romance, and action. Philip MacDonald was often criticized at the time for introducing too much suspense and action into his Anthony Gethryn novels, but as a result many of them are better reads today than clever puzzlers like Anthony Berkley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case where everyone talks and talks and nothing much happens.

Towards the end of the classical era even S.S. Van Dine felt the need for Philo Vance to get involved in a car chase and running gun fight (The Kidnap Murder Case). I never understood why dullness was supposed to be a literary virtue in the detective novel.

That said, R. Austin Freeman’s Dr. Thorndyke stories and novels contain few thrills, but the structure of the plot, the joys of watching Thorndyke’s careful and methodical investigation, and the reconstruction of the crime by Thorndyke at the end hold the reader as well as any shocker or thriller.

But then Freeman was, in Chandler’s words, “the best dull writer,” and Thorndyke a character who, while largely forgotten today, deserves to sit very near the top with Holmes, Father Brown, Poirot, and Maigret. In the right hands even dullness can be a virtue, though not one to be imitated by would be writers.

Mon 2 Mar 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini:

G. D. H. & MARGARET COLE – Knife in the Dark.

Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover; Dec 1941. The Macmillan Co., US, hardcover, 1942 (shown below).

G. D. H. and Margaret Cole were extremely prolific writers between the two world wars: individually and collaboratively, they published well over two hundred books of fiction, nonfiction, and verse.

G. D. H. was a prominent social and economic historian; his five-volume A History of Social Thought is considered a landmark work. Dame Margaret is best known for her biographies of Beatrice Webb and of her husband (The Life of G.D.H. Cole, 1971).

The Coles co-authored more than thirty “Golden Age” detective novels, beginning with The Brooklyn Murders in 1923, and six volumes of criminous short stories. Knife in the Dark is their next to last novel, and the only one to feature Mrs. Warrender as its protagonist.

“A naturally trim and tidy old lady,” Mrs. Warrender is the mother of private detective James Warrender (who affectionately calls her, among other things, “an incurably meddling old woman”). She is also solidly in the tradition of such “little old lady” sleuths as Miss Jane Marple and Hildegarde Withers, although less colorful than either of those two indefatigable crook-catchers.

Knife in the Dark takes place at a mythical ancient English university, Stamford, during the dark days of World War II. Kitty Lake — wife of Gordon Lake, a teacher of Inorganic Chemistry whose mother is a cousin of Mrs. Warrender’s — is stabbed to death during an undergraduate dance which she herself arranged.

Any number of people had a motive to do away with the mercurial Kitty, who had both a mean streak and a passion for other men; the suspects include her husband, an R.A.F. officer, a young anthropologist, a strange Polish refugee named Madame Zyboski (who may or may not be a Nazi spy), and a dean’s wife whom James Warrender describes as “an awful old party with a face like a diseased horse and a mind like a sewer.”

Like all of the Coles’ mysteries, this is very leisurely paced; Kitty Lake’s murder, the only one in the book, does not take place until page 104, and there is almost no action before or after. Coincidence plays almost as much of a role in the solution as does detection by Mrs. Warrender (who happens to be staying with the Lakes at the time of the murder); and the identity of the culprit comes as no particular surprise.

For all of that, however, Knife in the Dark is not a bad novel. The characters are mostly interesting, the university setting is well-realized, and the narrative is spiced with some nice touches of dry wit. Undemanding fans of the Golden Age mystery should find it diverting.

Mrs. Warrender’s talents are also showcased in four novelettes collected as Mrs. Warrender’s Profession (1939). The best of the four is “The Toys of Death,” in which Mrs. W. solves a baffling murder on the south coast of England.

The Coles also created three other series detectives, none of whom is as interesting an individual as Mrs. Warrender. The most notable of the trio is Superintendent Henry Wilson of Scotland Yard, for he is featured in sixteen novels, among them The Berkshire Mystery (1930), End of an Ancient Mariner (1933), and Murder at the Munition Works (1940); and in the collection of short stories, Superintendent Wilson’s Holiday (1928).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 1 Mar 2009

The following piece first appeared as a comment following

my review of the A&E television production of

The Doorbell Rang, in which I made some additional remarks that David follows up on too. — Steve

I agree the Chaykin and Hutton Nero Wolfe series is not only the best film version of Wolfe, but one of the best adaptations of a fictional sleuth to film (certainly to the small screen).

Both Edward Arnold and Walter Connolly, who played Wolfe in early films, decided to play him as a jovial and bluff type much like the millionaires and politicians they usually played, and it didn’t help that Lionel Stander (Max on Hart to Hart) was badly miscast as Archie (much less John Qualen as Fritz).

The sets were faithful to the books, though. (The two films were Meet Nero Wolfe, based on Fer de Lance, and The League of Frightened Men.)

Television did much better with the pilot film Nero Wolfe (1979) that starred Thayer David and Tom Mason. Based on The Doorbell Rang, it was a superior made-for-television film, and David and Mason were both good. They even did the scene from the book where Wolfe’s client (Anne Baxter in this one) spots the portrait of Wolfe’s father (Sherlock Holmes).

If memory serves Biff McGuire was Cramer and John Randolph played Lon Cohen. Frank Gilroy directed and scripted. The untimely death of Thayer David postponed the series, which eventually starred William Conrad and Lee Horsley, and the least said about that the better.

Wolfe did somewhat better on radio where the role was played by Santos Ortega and Sidney Greenstreet. If you’ve never heard them they are well done, and not hard to find. But running only a half hour, the series episodes seldom adapted Stout’s material.

As to why there is no American equivalent to Mystery or Masterpiece Theater, part of it lies in the fact the BBC is a government operation, and part the commercial nature of network and cable television. We’ll always get another version of Knightrider and seldom get a quality program like Nero Wolfe, and certainly nothing to resemble those adaptations of Lord Peter, Campion, Poirot, or Miss Marple.

Another factor is that many British series only commit to six to eight episodes a season so budgets aren’t as restrictive, and the actors can do other work while doing a series without having to leave the series.

That the Jim Hutton Ellery Queen, the Chaykin Wolfe, and the Spenser TV series were as good as they were and ran as long as they did are all minor miracles.

Eventually there will be a revival of classical tec films (everything comes back to some extent), and we’ll get a new round of American-made Agatha Christie’s with some poor actress as badly cast in the part of Miss Marple as Helen Hayes was, or a Peter Ustinov struggling with diminishing budgets and scripts.

But the sad fact is, it’s cheaper to generate material based on old series and follow trends than try to do something smart. It’s more cost effective to invent a tec series for the small screen than to buy the rights to a proven product and run afoul of fans’ preconceived ideas and the author’s desires.

It probably doesn’t help that today’s honchos have a better understanding of comics, science fiction, fantasy, movies, and 80’s television than mystery fiction. Our only hope is that somewhere down the line another cable network decides to gamble on something like the Nero Wolfe series and produces something worthwhile instead of more reality series and tiresome comedies and dramadies. But I wouldn’t hold my breath.

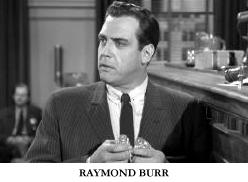

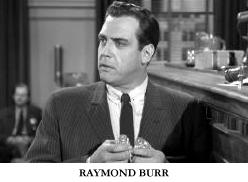

And I know I’m gilding the lily here, but there seems to have been a suggestion that Perry Mason debuted sometime around the creation of the Raymond Burr television series. Of course Mason appeared for the first time in the late 1930’s when Gardner was already a highly successful pulp author. (H. Bedford Jones officially passed the title king of the pulps onto Gardner.) Mason pushed Gardner onto the bestseller list and made him one of the most successful writers of all time.

Warner Brothers did a series of Mason movies with Warren William, Ricardo Cortez, and Donald Woods as Mason (at least one had Allen Jenkins as Paul Drake and Errol Flynn made his American film debut as a corpse in another). There was also 15 minute radio serial based on Perry, but it was never a particular success.

It wasn’t until television and Burr’s incarnation of the character that Perry finally conquered another market. Fans will recall a second attempt to do Perry with Monte Markham that met an early and much deserved end, and of course Burr’s return to the role in later years in a series of made for television movies.

Although Gardner was a major success as a mystery writer without Burr, it can certainly be argued that Burr so embodied the character that he took the whole thing to another level pushing Perry to a level closer to Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, and James Bond than the usual run of mystery icons. There is a good book, Murder in the Millions, that covers the mega sales of Gardner, Ian Fleming, and Mickey Spillane.

« Previous Page