June 2009

Monthly Archive

Sat 27 Jun 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Kathleen L. Maio:

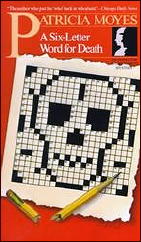

PATRICIA MOYES – A Six-Letter Word for Death.

Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, 1983. Holt Rinehart and Winston, US, hc, 1983. US paperback reprint: Holt/Owl, 1985.

In the late Fifties, as many of the Golden Age masters of the British mystery were retiring or expiring, new blood (so to speak) entered the field. Many of the younger generation turned their hands to more realistic mystery forms, but a few novices stayed with the old ways and true.

Such a writer is Patricia Moyes, whose dedication to the classic British puzzle has been a comfort to cozy fans since Dead Men Don’t Ski (1959).

A Six-Letter Word for Death is but the latest in a long-running series featuring Chief Superintendent Henry Tibbett of Scotland Yard and his wife, Emmy. It is a classic country-house mystery set on the Isle of Wight. A publisher invites a group of pseudonymous mystery authors called the Guess Who for a weekend house party.

Meanwhile, Henry (invited as guest expert and lecturer) has received a series of clues by mail crossword-puzzle sections indicating that the party guests may an have skeletons in their closets. When murder follows, Tibbett’s investigation intensifies to a classic, if overly melodramatic, confrontation with suspects and murderer.

Moyes manages to poke a bit of affectionate fun at mystery fiction and its creators. She also creates a traditional tale much more satisfying than some of her recent work set in the West Indies. Moyes takes a touch of the police procedural, a dash of the husband-and-wife mystery/adventure, and creates a very pleasing product in the style of the Golden Age.

A Six-Letter Word for Death is one of Moyes’s best mysteries of the last ten years. Other notable Tibbett cases are Murder a La Mode (1963), Johnny Under Ground (1965), and Seasons of Snows and Sins (1971).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 26 Jun 2009

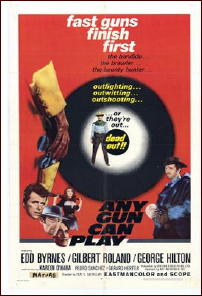

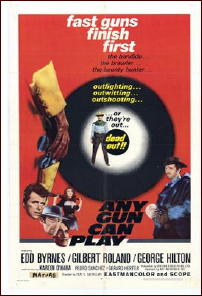

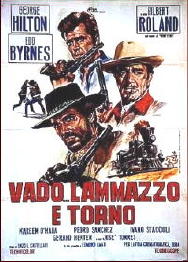

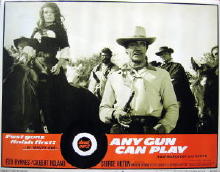

ANY GUN CAN PLAY. 1967, a/k/a Vado… l’ammazzo e torno. Made in Italy; dubbed into English. Edd Byrnes, George Hilton, Gilbert Roland, Kareen O’Hara (Stefania Careddu), Gerard Herter. Director: Enzo G. Castellari.

The opening scene is quite spectacular, and while the rest of the movie doesn’t quite match up, parts of it do, and it does let the moviegoer a pretty good hint of what they’re in for — a genial spoofing of a western movie genre, 1960s style, with more twists and turns in the plot line than a dozen Roy Rogers movies, and more unusual (and often spectacular) camera angles than a gross of Gene Autry films.

By 1960s style, and given the fact that the film was produced in Italy, I assume you realize that the particular type of movie that Any Gun Can Play is playing off against is that of the so-called “spaghetti western.”

I’d stopped watching westerns in the 1960s, and I’m no expert in the field, but I know enough to know that the three riders plodding their horses into town, as frightened onlookers peer out from behind curtained upper story windows, are takeoffs of Clint Eastwood in his trademark poncho, Lee Van Cleef in his ever-present black suit, and someone strongly resembling the steely blue-eyed Franco Nero as Django in the movie of the same name.

Credit where credit is due. I knew two of the three. The third one I needed a helping hand with, and it’s Steve M of Western Fiction Review whose suggestion in the comments I’ve just used. But here’s what’s important. What happens next will blow you away. It did me, and I know I wasn’t the only one.

The story itself begins only after this opening scene ends, as the notorious bandit Monetero (Gilbert Roland) makes plans with his gang to hold up the train that the job of Clayton, a tenderfoot banker (Edd Byrnes), depends on. The train is carrying a fortune ($300,000) in gold coins, and if the shipment doesn’t arrive safely, he’s likely to be given his walking papers.

On Montero’s trail, however, is “The Stranger” (George Hilton), a bounty hunter with a thirst for ready cash, whether for the reward money or the stolen gold… Oops. I missed telling you about that. The holdup goes off with nary a hitch (except for leaving a humongous body count behind), and a double cross on the part on one of the bandits means that the gold’s hidden somewhere not too far away, but exactly where? Dead men cannot say.

There is more than one double cross in what follows next, triple crosses — why not? — and even perhaps a quadruple cross or two. A fortune in gold coins does that to people’s minds.

There is a point, about two-thirds of the way through, where the subtly of the spoof so far — and for a long time the film is played so straight that you begin to believe that the opening scene was only an homage and not a hint of things to come — turns and becomes what is almost all out comedy, thus tending to spoil the effect.

A hint at the right place and at the right time may be all that’s needed — a wink from one of the players, perhaps, not much more — and although extremely well choreographed, the fight scenes tend to go on too long.

It’s all a matter of perspective, of course. What jiggles one person’s sense of humor immensely may need a much bigger poke to make another person smile or laugh. All in all, while I didn’t laugh out loud all that much, I certainly smiled a lot.

And, oh. One last thing. While the two young guys displayed their talents well, I think Gilbert Roland, at the age of 62, stole the show. Suave and utterly unflappable as the bandit Monetero, I think he showed Mr. Byrnes and Mr. Hilton a thing or two.

With a lifetime of filmmaking behind him, including a short stint as the movie’s Cisco Kid, he was at ease in his role as if he’d been a notorious Mexican bandit all his life.

Fri 26 Jun 2009

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

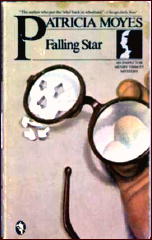

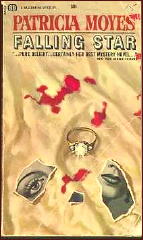

PATRICIA MOYES – Falling Star. Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, 1964. Holt Rinehart & Winston, US., hc, 1964. US paperback reprints: Ballantine U2244, 1966; Owl, 1982.

The publisher Holt, Rinehart, and Winston has been reprinting most of the mysteries of Patricia Moyes in its Owl series, and Falling Star has been one of them. While it is not one of her stronger books, most other authors would be glad to claim it.

The motive and murder methods are not convincing, however, and the number of suspects too limited for a really strong puzzle. Nonetheless, the author’s experiment of eschewing third-person narration in favor of a story teller who is a movie executive and also a bit of a prig (and not too bright) works well.

Also, Moyes’s series detective, Henry Tibbett, continues to be likable and efficient, if somewhat bland.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988 (slightly revised).

“Patricia Pakenham-Walsh, aka Patricia Moyes, was an Irish-born British mystery writer. [She] was born in Dublin on January 19, 1923 and was educated at Overstone girls’ school in Northampton. She joined the WAAF in 1939. In 1946 Peter Ustinov hired her as technical assistant on his film School for Secrets. She became his personal assistant for the next eight years.

“Her mystery novels [beginning with Dead Men Don’t Ski in 1959] feature C.I.D. Inspector Henry Tibbett. One of them, Who Saw Her Die (Many Deadly Returns in the US) was nominated for an Edgar Allan Poe Award in 1971.

“She married photographer John Moyes in 1951; they divorced in 1959. She later married James Haszard, a linguist at the International Monetary Fund. She died at her home in the British Virgin Islands on August 2, 2000.”

Fri 26 Jun 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

LOUIS TRACY – The Postmaster’s Daughter. Cassell, UK, hardcover 1917. Edward J. Clode, US, hc, 1916.

John Menzies Grant is taking an after-breakfast stroll in the garden of The Hollies, a charming house just outside the hamlet of Steynholme, Sussex. An ex-officer and now writer, he’s another of the typical Golden Age “healthy, clean-minded young Englishman” so sadly lacking in detective fiction these days.

But what is not lacking is a body — in this case a bound woman dragged from the river at the end of a line tied to Grant’s side of the river.

Grant recognises the woman as actress Adelaide Melhuish, to whom he had proposed marriage three years before. He then discovered she was married, and her suggestion he pay her husband to facilitate a divorce so disgusted Grant it precipitated their parting.

He had not seen her since, except for her face in the window, he thought he had glimpsed fairly late the evening before, but which he had dismissed as his imagination running riot.

The other woman in the case is a mere slip of a girl, Doris Martin, the postmaster’s daughter of the title. She lives across the river and she and Grant signal back and forth from home and garden. There is an as yet unacknowledged attraction between them, and the pair were in Grant’s garden the evening of the murder stargazing at Sirius at a time deduced to be not long before the murder took place.

It transpires Miss Melhuish had been in Steynholme for a couple of days asking questions about Grant and his friends and doings, and so suspicion naturally falls on him. Feelings start to run high in the village, fanned by the arrival of Isidor G. Ingerman, Miss Melhuish’s husband, who hints at a suit for alienation of affection against Grant and is otherwise quite beastly.

Grant has some moral support from Miss Martin as well as the owner of another pair of boots which take up residence under his dinner table, this particular set belonging to Grant’s close friend and global adventurer Walter Hart, whose conversational turns of phrase would make a number of present day humorists envious.

Tracy’s delightful pair of dueling Scotland Yard detectives solve the mystery, although the eccentric Charles Furneaux initially turns up without his more stolid investigative partner James Winter, who does not get onstage until about half way through the book.

My verdict: This is the sort of novel where the reader is drawn along at a rattling pace. There are few clews and much obfuscation, with comic interest added by badinage between the Scotland Yard men and Hart.

Readers may quibble with how some of the evidence is obtained, but the shifting moods of the local residents are well portrayed and the mystery ends with a strong denouement in the hamlet’s main street, followed by a brief “what happened next” chapter tying up the loose ends. It’s fair to say cozy fans as well as those enamored of the Golden Age of Detection will enjoy this novel.

Etext: http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/0/1/1/10110/10110.txt

Biblio-biographical data:

From Wikapedia: “Louis Tracy (1863-1928) was a British journalist, and prolific writer of fiction. He used the pseudonyms Gordon Holmes and Robert Fraser, which were at times shared with M. P. Shiel, a collaborator from the start of the twentieth century.”

For information on Tracy’s collaborations with M. P. Shiel, this website may tell you all you need. For a complete bibliography of Louis Tracy’s own work, a chronological checklist complied by John D. Squires can be found online here.

Previously reviewed by Mary Reed:

The Strange Case of Mortimer Fenley, 1915.

Number Seventeen, 1916.

Fri 26 Jun 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

SO LONG AT THE FAIR. Gainsborough (UK), 1950; Eagle-Lion/United Artists (US). Jean Simmons, Dirk Bogarde, David Tomlinson, Austin Trevor, Honor Blackman, Andre Morell, Felix Alymer, Cathleen Nesbitt Screenwriters: Hugh Mills & Anthony Thorne, based on the latter’s novel (Heinemann, 1947). Directors: Terence Fisher & Anthony Darnborough.

Ah, this one is a charmer, and all the more fascinating because it is based on what well may be a true story. Simmons is Vicky Barton a young Englishwoman traveling with her brother Johnny (David Tomlinson) to the famous Paris Exposition of 1896. Her head is filled with romance and wonder and dreams of adventure — that are about to turn into nightmare.

The brother and sister arrive in Paris and check into their nice upper middle class hotel, they have a night on the town in which they meet British artist George Hathaway (Dirk Borgarde) who is living and working in Paris, and a balloonist who is making an ascent for the Exposition before returning home for an early night so they can take in the Exposition the next day.

The day dawns bright and beautiful and Simmons goes to awaken her brother who apparently has slept in.

Only to find his room is no longer there.

Confused and more than a little panicked she calls on a maid. Who informs her there has never been a room there and no such room number as the one she insists her brother was staying in. She goes downstairs to the manager — and is told that she arrived alone, checked in alone, and they have never seen nor heard of her brother. Her name alone is on the reservation and her name alone is in the registration book.

Of course we’ve seen the brother so we know something is up, but from here on the film becomes a mix of thriller, detective story, and even a touch or two of the Grand Guignol as Simmons makes increasingly desperate attempts to convince the authorities in the form of a French Police Commissaire (Austin Trevor) and those around her she is sane and really has a brother before they lock her away, as no one seems to believe her, not even the British consul.

She remembers the balloonist and rushes to see him eluding those who want to lock her up, but arrives too late, he has made his ascent. And as she watches in horror his balloon bursts into flames and he falls to his death.

Finally she remembers the young artist who was so kind. And to her relief finds him. Of course he recalls her brother. But it proves no help. The police simply assume he is trying to seduce her by claiming to believe her preposterous story. After all, there is no evidence save the word of two foreigners, and why would the hotel lie, and risk a scandal during the most important event for tourism in French history?

It all seems lost until Bogarde’s artist eye takes in one telling detail.

The hotel has one more balcony on the brother’s floor than it has rooms …

I won’t give away the secret, save to say it is both shocking and offers a touch of almost gothic horror to the proceedings — something both horrible and yet not only believable, but in this case possibly true.

A film like this lives on the qualities of cast, script, direction, and almost as importantly the costumes and sets, and this one is a beauty to look at. Terence Fisher, who would helm many of the best of the famed Hammer horror films, directs with a sure hand, and Simmons’ fine balance between hysteria and spunk keeps the viewer pulling for her even we start to doubt what we have seen. The Paris of the Belle Epocque is evoked with real skill, and you may not even notice that all the French have British accents. At least you may not mind.

This is a small gem of a film, and should be appreciated in that spirit. It’s what might be called a “curious tale,” and taken in that spirit, it is both mystifying and intriguing with a payoff as good as any murder, spy, or horror film. Plus there is the bonus that this one may have actually happened, if not exactly like this.

It’s a perfect little film that achieves everyone of its modest goals and does so with such charm and ease it puts many bigger and more ambitious films to shame. Approach it in the right mood, and the right frame of mind, knowing it is as much a cautionary fable as a suspense film and you’ll find it succeeds at what it sets out to do.

There is some question as to whether this tale ever really happened, and if it did during which French Exposition, but it’s a great story true or not, and handled here with the maximum of style and skill. Let the historians argue about the facts and enjoy the fiction, and next time you travel, carry a camera — and maybe a few witnesses. You never know when your hotel room is going to disappear.

Note:

Austin Trevor, who plays the Police Commissaire, was well suited to play detectives. He had previously played Hercule Poirot and Philip MacDonald’s Anthony Gethryn. It was a photo of Trevor as Poirot that accompanied the obituary for the character that ran in the New York Times upon the publication of Curtain.

Thu 25 Jun 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

THE GUN HAWK. Allied Artists, 1963. Rory Calhoun, Rod Cameron. Ruta Lee, Rod Lauren, Morgan Woodward, Robert J. Wilke, John Litel , Lane Bradford. Director: Edward Ludwig.

Over the years, Monogram, the 1930s and 40s Poverty Row motion picture company, morphed into Allied Artists, and by the time of The Gun Hawk they were making B-westerns in color, but they were still very much B-westerns.

This has the usual stigmata of the genre: bad script, bad acting, low budget … but it’s lifted out of the ordinary by Rory Calhoun’s ghoulish portrayal of a dying gunman determined to go out on his own terms.

He’s counseled by veteran good-guy Rod Cameron and hounded by veteran bad-guy Robert Wilke, but this is basically Calhoun’s show, and he makes for fascinating viewing as he prowls about the screen, obviously dead from the moment he walked on; such a finely honed performance, one really wishes there were a decent movie somewhere around.

The Gun Hawk also offers a small part from an actor who specialized in them, Lane Bradford. Bradford came on in the waning days of Republic serials and series westerns, and he never did anything especially noteworthy. (Well, he did try to blow up the planet while dressed in purple sequins for Zombies of the Stratophere, which was something of an anomaly.)

But in the days when the once mighty outlaw gang had dwindled down to two or three henchmen for reasons of economy, he could always be seen somewhere in the background, looking formidably evil with his lantern jaw and broken nose, and getting punched out by Rocky Lane or Whip Wilson.

Here he has a good time bullying the town drunk till Calhoun steps up, and it’s nice to see Bradford, after all these years, still dealing out his brand of special nothingness.

Thu 25 Jun 2009

LESLEY EGAN – Look Back on Death (Doubleday/Crime Club, 1978.

Lawyer Jesse Falkenstein’s preoccupation with parapsychology is evident from page one on. Confirmed skeptics of ESP, clairvoyance, and mediums who can contact spirits of the dead are warned that while this case of murder which occurred eight years earlier does contain a good deal of detection via exhaustive legwork, the source of the final clue is sure to irritate their sensitive sensibilities more than a little.

Egan, who also writes the Dell Shannon books, otherwise does her usual fine job with dialogue and sharp characterization.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979 (very slightly revised).

Biblio-biographical data:

From Wikipedia: “Barbara ‘Elizabeth’ Linington (1921 – 1988) was a prolific American novelist. She was awarded runner-up scrolls for best first mystery novel from the Mystery Writers of America for her 1960 novel, Case Pending, which introduced her most popular series character, LAPD Homicide Lieutenant Luis Mendoza.

“Her 1961 tome, Nightmare, and her 1962 novel, Knave of Hearts, another entry in the Mendoza series, were both nominated for Edgars in the Best Novel category.”

Besides mystery fiction under her own name, Leslie Egan and Dell Shannon, Elizabeth Linington also wrote other crime and detective as by Anne Blaisdell and Egan O’Neill.

While she is considered an early female pioneer in the field of police procedurals, there are others, of course, such as Helen Reilly‘s Inspector McKee books, which preceded hers by many years.

In later years Linington was criticized for her lack of research and technical accuracy, fatal flaws as far as fans of the field were concerned. She was also noted for her membership in the ultra-right wing John Birch Society. Whether for either of these reasons or others, her books are not nearly as popular as they were during her lifetime.

Thu 25 Jun 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller:

CLARISSA WATSON – The Fourth Stage of Gainsborough Brown. David McKay, hardcover, 1977. Reprint paperbacks: Penguin, 1978; Ballantine, 1986.

Clarissa Watson is co-owner and director of an art gallery on Long Island, and she puts her knowledge of the art world to good use in her three novels about artist and gallery assistant Persis Willum.

Her depiction of the art world — its trendiness, petty jealousies, passions, and intrigues — is sure, and fleshed out with memorable characters. While many of the eccentrics Watson portrays are representative of real types who frequent museum openings and galleries, they are never stereotypical; and Persis herself, an independent but vulnerable thirty-six-year-old widow, is a delight.

The title character of this first novel, Gainsborough Brown, is an artist of flamboyant reputation — and definitely not a delight. Painters go through many “stages” in their work; at the time the book opens, “Gains” is in his third major stage; before he reaches his fourth, he is dead.

After Gains drowns in the swimming pool at a birthday party that Persis’s Aunt Lydie (an art patron and another extremely appealing character) has thrown for herself, Persis decides his death was no accident. And as an employee of Long Island’s North Shore Gallery, which handled the artist’s work, she feels compelled to find out who killed him and why.

Armed with an unusual detective’s tool — a sketch pad — Persis moves in what she hopes is an unobtrusive manner through the chic art world, from Manhattan to Paris, from elegant galleries to a studio full of cruelly satiric sculpture. Unfortunately, her investigative efforts have not gone unobserved, and she comes upon the solution to her first case at considerable danger to herself.

Watson’s writing, like her heroine, is witty and stylish, and her plot is full of surprises. The other Persis Willum novels are The Bishop in the Back Seat (Atheneum, 1980) and Runaway (Atheneum, 1985).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Bibliographic update:

There were two additional books in the series, both published after the 1986 edition of 1001 Midnights. From the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin: Last Plane from Nice (Atheneum, 1988) and Somebody Killed the Messenger (Atheneum, 1988).

Wed 24 Jun 2009

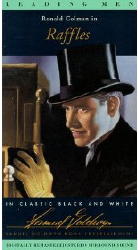

RAFFLES. Samuel Goldwyn, 1930. Ronald Colman, Kay Francis, Bramwell Fletcher, David Torrence, Alison Skipworth, Frederick Kerr. Based on the story collection (and the subsequent play based on it) The Amateur Cracksman (1899) by E. W. Hornung. Directors: Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast (uncredited); fired and replaced by George Fitzmaurice.

I had a strange experience while watching this movie, and of course I’m ready to tell you about it. Due to circumstances beyond my control, I watched this movie over the span of two successive evenings, even though it’s only a miserly 72 minutes long.

I’d enjoyed the first half immensely and was looking forward to the second half with considerable anticipation, only to find the second half a sorry letdown, and I for the life of me, I couldn’t figure out why.

What had happened? Were they off budget and the production crew had to wrap things up too quickly? Scouring the Internet after the fact, it seems as though something like that did happen — as you will spotted yourself if you haven’t skimmed through the credits above too quickly.

A. J. Raffles, as you may know, is well-known even today as “The Amateur Cracksman,” quite fictional of course, and as a character, a gentleman burglar and house thief created by E. W. Hornung, who married a sister of Arthur Conan Doyle. The stories of his exploits were quite the rage in late Victorian England (approximately 1898 to 1905), but instead of my telling you more about them, I’d prefer to send to Mary Reed’s long and informative article about them, which you can find on the primary Mystery*File website.

In this first talking picture version of the Raffles stories, it is Ronald Colman, of the well-modulated British accent (and therefore a perfect choice in that regard) who plays the title character, and Bramwell Fletcher who plays his good friend and close associate, Bunny Manders. (Fletcher was last mentioned on this blog as one of the players in the The Mummy, which came out in 1932, but he was young enough to wind up his career in television in 1967.)

If my count is right, there were five earlier silent films with Raffles as a character. This 1930 version was followed by another in 1939, the one that starred David Niven, which I wish I could tell you that I’ve seen, but which I have to admit I have not. In spite of a good cast, however, including Olivia de Havilland, it does not seem to have gathered very good reviews.

But as you won’t have forgotten my saying so earlier, this earlier production showed a lot of promise. After proposing marriage to his lady friend Gwen (Kay Francis), Raffles promises himself an end to his career as a burglar, only to be confronted with Bunny’s gambling debts — a matter of some thousand pounds — with only a weekend between then and disaster.

So it’s off to the country and the Melrose mansion, which is also the home, not so coincidentally of the Melrose diamonds. And not only are Raffles and Bunny present, along with the usual assortment of house guests, but also a gang of lower class thieves with a Scotland Yard inspector hot on their trail, all of which are complications that Raffles had not counted on.

And when Gwen suddenly appears as well … and this is where I had to stop watching on the first evening.

To say that the next night’s continuing viewing proved disappointing is an understatement indeed. From a well-paced first half, an A-level production, the second half is a helter-skelter mish-mash of attempted break-in’s — some successful, some not — close calls, sudden shifts of scene, and gaps in the story line that a hansom cab could have plowed through easily.

There is one plus, though, that I would be remiss in not pointing out. Kay Francis’s character seems to light up from the slightly soporific to a lady with a mission and a delightful gleam in her eye when she deduces the truth about the man she’s promised her heart to. What a delightful adventure! she thinks (in those not-so-innocent pre-Code days).

And it should have been, and what’s more, it could have been, I’d like to believe, and I do.

Wed 24 Jun 2009

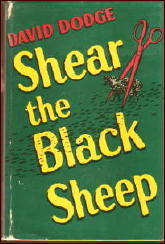

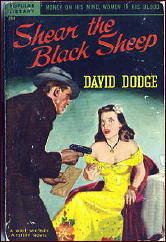

DAVID DODGE – Shear the Black Sheep. Popular Library 202, paperback reprint; no date stated, but circa 1949. Hardcover edition: The Macmillan Co., 1942. Magazine appearance: Cosmopolitan, July 1942.

After I finished reading this, the second murder mystery adventure of accountant detective Jim “Whit” Whitney, I went researching as I usually do, and it didn’t come as any surprise to learn (from a website devoted to David Dodge) that Dodge was also a CPA by profession, and that he started writing mystery fiction only on a dare from his wife.

Although Dodge went on to another series (one with private eye Al Colby) and after that several standalones, there were only four books in the Whit Whitney series, to wit:

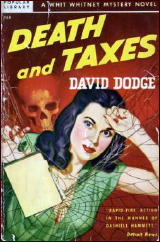

Death and Taxes. Macmilllan, hc, 1941. Popular Library 168, pb, 1949.

Shear the Black Sheep. Macmillan, hc, 1942. Popular Library 202, pb, 1949.

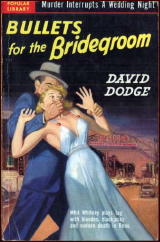

Bullets for the Bridegroom. Macmillan, hc, 1944. Popular Library 252, pb, 1950.

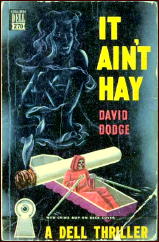

It Ain’t Hay. Simon & Schuster, hc, 1946. Dell 270, pb, mapback edition, 1949.

You can find much more detailed entries for each of these books at the David Dodge website, which includes a complete bibliography of all of his other books, both fiction and non-fiction. Not to mention his plays, his magazine stories, the articles he wrote and all of the radio, TV and movie adaptations of his work, the most well-known of which is To Catch a Thief, the Cary Grant and Grace Kelly film from 1955. Comprehensive is an understatement, and it’s definitely worth looking into, just to see a bibliography done right.

As for Whit Whitney, his home base is San Francisco, but in Shear the Black Sheep he is talked into taking a case in Los Angeles over the New Year’s Eve holiday weekend. Against his better judgment, he agrees to check into the activities of a client’s son, who seems to be spending too much of his father’s money in the business they’re in. They’re a wool brokerage firm — hence the title. The son has also left his wife and new-born baby. Is there another woman?

Assisting Whitney — or making her way down to LA on her own to spend the holiday with him, or as much of it as there is left after Whit’s investigative duties are over– is Kitty MacLeod, “the best-looking girl in San Francisco, and pretty clever as well,” as she’s described on page 12.

I’ve not read the first book in the series, and make no doubt about it, I will, but in that book (according the short recap on just about the same page) Whit’s former partner was murdered and at the time, Kitty was his wife.

It’s now six months later, and Whit and Kitty have become very close. Whit is beginning to worry that some of his colleagues are starting to talk. There had even been some talk at the time that Whit had had something to do with Kitty’s ex’s departure from life, and getting out of the jam at the time seems to be the gist of the story in Death and Taxes.

But that was then, and this is now. There is indeed a woman involved, as suspected — getting back to the case that Whit was hired to do — and the woman leads to a hotel room, and in the hotel room are … gamblers. A crooked card game, and the black sheep is getting sheared.

It is all sort of a light-hearted tale, in a way, but then a murder occurs, and a screwy case gets even screwier — in a hard-boiled kind of fashion. Let me quote from page 160. Whit is talking to his client, who speaks first:

“I don’t think it’s wise to interfere with the police, Whitney.”

“I won’t interfere with them. I’d cooperate with them except that they’ve told me to keep out of it. I want you to know how I feel, Mr. Clayton. You hired me to find out what Bob was doing with your money, and to stop it. I found out what was going on, but I thought the best way to stop it was to let these crooks get out on a limb, and then saw it off behind them. I thought I could protect your money and show Bob what was happening at the same time. I guessed wrong. I don’t know who killed […] or why he was killed, and I don’t think I’m responsible for his death, but I’m in a bad spot and I’d like to bail out of it by myself — for my own satisfaction. The police needn’t know what I’m doing. I don’t have to tell you that I don’t want to be paid for it, but if you haven’t any objection, I’ll try to find out who killed […] and get your money back.”

Here are a few lines from page 170, at which point things are not going so well:

He got off the bed and prowled thoughtfully around the room in his stocking feet, still holding the beer glass. What would Sherlock Holmes do with a case like this? Probably give himself a needleful in the arm — Whit drained his beer glass — and deduce the hell out of the case.

Whit tried deduction.

Those were the days when mystery thrillers were also detective novels. After a long paragraph in which Whit tries out his best logic on the tangled threads of the plot, and who was where and when and why:

It was a pretty wormy syllogism. As a deducer Whit knew he was a lemon when it came to logic, and he was an extra-sour lemon because he didn’t know enough about Bob Clayton to figure out what he might do in a given set of circumstances. Such as having a pair of football tickets to dispose of, for example. Ruth Martin might have known where they went, but didn’t, ditto Mrs. Clayton, ditto John Clayton. Jack Morgan was the next one to try.

What’s interesting is that Kitty has more to do with solving the case than Whit does. Things happen rather quickly at the end, and if all of the loose ends are (or are not) all tied up, no one other than I seems to think it matters, as long as the killer is caught — who was not someone I suspected, or did I? I probably suspected everyone at one point or another.

I also wonder if what happens on the last page has anything to do with the title of Whit Whitney’s next adventure in crime-solving. Read it, I must. And I will.

— March 2006.

[UPDATE] 06-24-09. That’s a promise to myself that I haven’t kept yet, alas, and re-reading this review (and looking at those paperback covers) gives me all the resolve I need to follow through. You can count on that and take it to the bank. Non-negotiable.

« Previous Page — Next Page »