June 2009

Monthly Archive

Sun 21 Jun 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

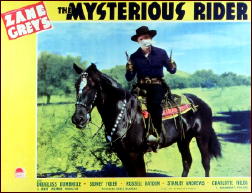

THE MYSTERIOUS RIDER. Paramount, 1938. Douglass Dumbrille, Sidney Toler, Russell Hayden, Stanley Andrews. Weldon Heyburn, Charlotte Field, Monte Blue. Based on the novel by Zane Grey. Director: Lesley Selander.

Douglass Dumbrille is the kind of actor one vaguely remembers as a perennial nasty who never really scaled the heights.

He had his moments, though: pushing bamboo shoots under Gary Cooper’s fingernails in Lives of a Bengal Lancer, chasing Jackie Cooper up the rigging in Treasure Island (center right), or looking down his nose at the Marx Brothers in The Big Store, happy times in a busy career that somehow never achieved the status of, say, Lionel Atwill or Vincent Price.

Imagine my surprise, then, when he turned up as the out-and-out hero of an engaging B-Western called The Mysterious Rider. Dumbrille stars here for his first and only time as Pecos Bill, the nom du rue of a legendary highwayman who gets a hankerin’ to revisit the old homestead he left twenty years ago, wanted for murder.

From this point, the story veers toward The Odyssey, with Pecos returning to his old ranch unrecognized, greeted by the dogs and finding his daughter beset by unworthy suitors-then setting about to put things right.

Mysterious Rider shows what magic can be done by a capable director with familiar material. Lesley Selander spent thirty years in Bronson Canyon, Gower Gulch and other stomping grounds of the B-Western, churning out vehicles for Hopalong Cassidy, Buck Jones and Tim Holt, and he always took it seriously, investing his work with inventive camera angles, capable stunting and (most important) snappy pace.

Here given a modestly off-beat story and an unlikely star, he turns out a fast, fun film, enlivened considerably by Dumbrille’s evident delight in playing a good guy — although his typecast background makes it easy to believe that he may well have been a road agent.

One additional note: in 1957 Dumbrille, at age 70, married the 28 year old daughter of his friend and fellow character actor Alan Mowbray. They were still married at the time of his death, seventeen years later.

Sun 21 Jun 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

Reviews1 Comment

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

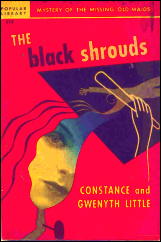

CONSTANCE & GWENYTH LITTLE – The Black Shrouds.

Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1941; Collins Crime Club, UK, hc, 1942, as by as by Conyth Little. Paperback reprints: Popular Library #112, n.d. [1946]; Rue Morgue Press, trade pb, 2002.

To find fame — her father already has a fortune — on the stage, Diana Prescott has come to New York City. What she discovers, however, is horror at Mrs. Markham’s boarding house, which is occupied by the usual oddities one finds at fictional boarding houses and maybe even the real ones.

Two elderly and old-maid sisters, an absolutely harmless pair, are found murdered — bludgeoned and then gassed.

It’s obvious it’s an inside job, but the police, in more ways than one, haven’t a clue. Even when another resident disappears and items appear and disappear and books and other objects are burnt in the furnace, the officials are at a loss.

Though frightened a fair part of the time, Prescott does her own investigating, primarily to avoid playing bridge with her father.

For reasons unknown, but perhaps because the inhabitants are generally eccentrics, I enjoy mysteries with boarding-house settings. I’d have enjoyed this one anyhow because the Littles are quite amusing writers, and their Miss Giddens is a delightfully nutty character.

And if my recommendation isn’t enough, I refer you to Something Wicked, by Carolyn G. Hart, in which her wonderful bookstore, Death on Demand (Annie Laurence, prop.), put The Black Shrouds in its window with several other books to illustrate humor in the mystery.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988.

EDITORIAL COMMENT. For more information on the authors, who wrote 21 mystery novels in very much the same vein as The Black Shrouds between 1938 and 1953, there is no better place to send you than to the Rue Morgue Press website, where publishers Tom and Enid Schantz say in part:

“If these two Australian-born sisters from East Orange, New Jersey, are not better known today, it’s probably because they chose not to write a series.

“But if the characters in each of their books had different names, you could always recognize a Little heroine, whether she was a working woman or a spoiled little rich brat. Nothing held her back or kept her from speaking her mind, which may explain why she so often fell under suspicion when a body turned up…”

To this date, Rue Morgue has reprinted 20 of the 21 novels, all but The Black Gloves (1939). Note that the word “Black” appeared in all of the books by the Little sisters except the first one, The Grey Mist Murders (1938).

Sat 20 Jun 2009

Posted by Steve under

Covers ,

Reviews[8] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

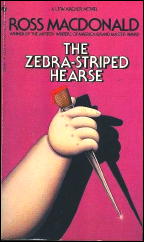

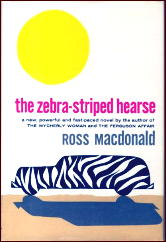

ROSS MACDONALD – The Zebra-Striped Hearse. A. A. Knopf, hardcover, 1962. Bantam F2715, paperback reprint; 1st printing, January 1964. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including those seen below.

If you somehow missed Ross Macdonald’s The Zebra-Striped Hearse in its hardcover edition or in one of the previous twelve (!) Bantam printings, you get another chance, for that publisher has reprinted it again, after a four-year hiatus.

Because this is one of the best in an outstanding series of private-eye novels, it is a book you shouldn’t miss. You’ll find many elements taken from the author’s own life and placed into the investigation of his detective, Lew Archer, including the runaway father, the canyon forest fire, and California’s unique culture, accurately presented in a book that ranges the state from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

We see the compassion for which Archer is justifiably known, but there is also ample evidence of his intelligence as his creator has him quote Dante in a conversation so well written that it fits in seamlessly.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988 (very slightly revised).

Covers:

Shown above is the cover of the 12th printing that Marv was referring to. Others covers that have graced this book are shown below, but to my mind, none of them surpasses the Knopf hardcover First Edition:

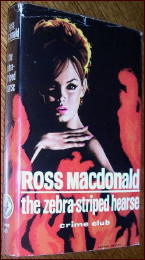

Here’s the hardcover UK first edition, from Collins Crime Club, 1963:

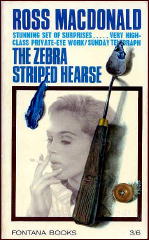

And I believe this to be the first UK paperback edition, published by Fontana in 1965:

To finish up this short display, a paperback edition from France, Éditions J’ai Lu #1662, 1984.

[UPDATE] 06-22-09. Submitted by Juri Nummelin, a hardcover edition published in Finland:

See the comments for a link to a short write-up about Juri about Macdonald, including this book.

Sat 20 Jun 2009

THREE FROM THE SMALL SCREEN, PART 2.

Movie Reviews by David L. Vineyard

This is the second in a series of three reviews covering movies that were made for TV in the 1960s and 70s, the heyday of such film-making. Most of them were no more than ordinary, to be sure, but a few were well above average — small gems in terms of casts, plotting and production.

Previously on this blog: How I Spent My Summer Vacation (1967).

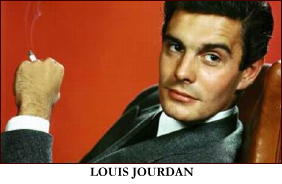

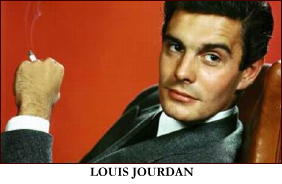

RUN A CROOKED MILE. Universal/NBC-TV, 18 November 1969. Louis Jourdan, Mary Tyler Moore, Alexander Knox, Wilfred Hyde Whyte, Stanley Holloway, Alexander Knox, Laurence Naismith, Ronald Howard. Teleplay: Trevor Wallace; director: Gene Leavett.

Richard Stuart (Jourdan) is a tutor who stumbles onto a murder in a remote English mansion. When he comes back with the law, the body is gone and he is ridiculed.

Certain he isn’t mad, he returns to London and hires a private detective, Stanley Holloway. Shortly after that he discovers a key to a room in the mansion, and is knocked unconscious.

When he wakes up, he finds he is on the Cote d’Azur, and his name is Tony Sutton, a wealthy playboy who took a blow to the head while playing polo. He’s married to the beautiful American heiress Elizabeth Sutton (Mary Tyler Moore) and he has lost five years of his life.

Who can he trust? Is his wife part of the conspiracy? Just what nest of snakes did he stumble into five years earlier?

Obsessed with finding out he returns to London to find Holloway now quite well to do and the Yard’s Inspector Huntington (Howard), not interested. Nevertheless he perseveres follows the clues back to the mansion owned by Sir Howard Nettington (Knox) and with Elizabeth’s help solves the mystery, uncovers a conspiracy, and brings down the high placed villains.

I suppose you do have to wonder why he would be so anxious to solve the murder of a stranger and risk a very good life with a rich and beautiful wife who loves him despite the fact he hasn’t been any prize as Tony Sutton, but if people behaved normally in these things, nothing would ever happen.

Run a Crooked Mile is a clever sub-Hitchcock exercise in the Buchan vein with handsome sets, and a fine cast. It moves quickly and relies on the considerable charms of Jourdan and Moore to get through whatever lags in logic that might plague you.

It’s one of those films where almost no one is quite who they seem to be, but it is done with such style and competence that it plays more like a feature than a made-for-TV film. Of the three films that will be reviewed herem it probably most deserves release on DVD.

It’s smart, funny, and suspenseful, attractive to look at, and much more literate and intelligent than it has to be. Howard, Knox, Whyte, Holloway, and Naismith all contribute nicely to the fun. In many ways it plays like a good episode of The Avengers, droll. literate, and full of twists.

Coming soon:

Probe (1969), with Hugh O’Brien and Elke Summer.

Fri 19 Jun 2009

SWAMP WATER. 20th Century-Fox, 1941. Walter Brennan, Walter Huston, Anne Baxter, Dana Andrews, Virginia Gilmore, John Carradine, Mary Howard, Eugene Pallette, Ward Bond, Guinn Williams. Based on the novel by Vereen Bell. Director: Jean Renoir.

From what I’ve learned recently that I didn’t know about director Jean Renoir before I sat down to write up some thoughts about this movie, his first American film, Orson Welles considered him the greatest director of all time, and he was voted the 12th-greatest director of all time in a poll conducted by Entertainment Weekly magazine.

I think I could easily go along with Orson Welles. Even though the critics don’t seem to have thought too highly of Swamp Water, the general public did, and it was one of Fox’s highest grossing films of 1941. I agree. The general public was right this time.

There is a lot to like in this film, even though it doesn’t seem to be regarded even now as one of Renoir’s best, and while I haven’t done so yet, I think that it will bear one or more viewings by me, very easily.

That the atmosphere of a small Georgian community on the edge of the huge Okefenokee Swamp is portrayed in a highly realistic fashion almost goes without saying — or maybe it doesn’t, so I will.

It’s not clear how someone having come to this country straight from Europe could have visualized and reproduced life in a small Southern town so well that it feels like everyone in the movie had lived there all their life — but that’s the feeling I received, only slightly cliched in (unfortunately) standard Hollywood fashion.

Of course it helps that a good portion of the movie was filmed on location. The only serious omission, I think, is that I do not remember seeing any blacks in the film, only whites, and yet even so, the idea that not all men were created equal in the US in the 1940s still manages to make itself felt, if even only subtly.

And it is a crime film, although when it comes to movies, as you will have seen on this blog, I’ve been insisting on that less and less as time has gone on. You could even call it “swamp noir.” The mood is dark enough at times, as life seems to go wrong at every turn for trapper Ben Ragan (Dana Andrews) after he stumbles across fugitive from justice Tom Keefer (Walter Brennan) hiding in the swamp while hunting for his lost dog Trouble.

Agreeing not to turn Keefer in, Ben returns home and tries to keep Keefer’s secret from everyone but the latter’s daughter, the wild-haired Julie (Anne Baxter), who’s treated as little more than a scullery maid by the family who has taken her in, but with little success, no thanks to his jealous girl friend Mabel MacKenzie (Virginia Gilmore), blonde and far more perfectly coiffed.

Ben is also on the outs with his father Thursday (Walter Huston), who second marriage to Miss Hannah (Mary Howard) is beginning to falter, thanks to the attention being paid to her when Thursday is gone by the pathetic and largely contemptible Jesse Wick (John Carradine).

There’s a lot more to the story, with all of the pieces dovetailing nicely, and all of the players fitting their parts to a T, especially (and this came as a surprise to me) Walter Brennan, whom I usually think of as overacting greatly, but not in this role. As a speaker of soliloquies to the stars and to nature in general, his presence on the screen I found to be as mesmerizing as any I can recall in quite a while.

Not that he was on screen a high percentage of the time. The honor in that regard goes to Dana Andrews, whose Southern accent was the most pronounced, but which started to sound more and more natural as the movie went on. As did the movie itself.

Flawed by more of a sentimental ending than I expected, perhaps, and also because (and this is another perhaps) Renoir had the movie selected for him rather than the other way around, this is a movie that I enjoyed immensely. If you have a chance to see it, given that you’ve read this review all the way here to the end, I recommend it to you highly.

[UPDATE] 6-20-09. First an email note from Bill Crider, who says, “You know my fondness for this kind of book means that I own a copy.” And here it is, or the cover, at least, thanks to Bill:

Bantam 97, June 1947. (Originally Little Brown, hardcover, 1941.)

Then another note, this one from Al Hubin, who agrees that the book belongs in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, not previously incuded. He also points out the existence of the second filmed version, Lure of the Wilderness, 1952, with Jean Peters and Jeffrey Hunter, and directed by Jean Negulesco.

Fri 19 Jun 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

MALDEN GRANGE BISHOP – Scylla. Ace Double D-40, paperback original; 1st printing, 1954.

The author of Scylla, Malden Grange Bishop, is a writer better known for his non-fiction (including a book on LSD that pre-dates the psychedelic era).

Scylla is considerably less groundbreaking, a standard tale of domestic murder, not very intelligently planned nor, surprisingly, found out. Its marginal virtues, in fact, lie in the very ordinariness of concept and execution.

The book reads as if it were written to fill out the back half of an Ace Double (which it does; the flip side is William Irish’s Waltz into Darkness) with the standard elements of sex, murder and not much else, and the writing is never bad enough to quit reading nor good enough to be memorable.

What emerges reminds me of what Raymond Chandler said about giving murder back to the kind of people who commit it: Scylla, the villain of the piece is just a half-smart housewife, bored with her husband. She kills him not so much for money as because he simply irritates her — one of the leading motives for murder, if truth be known.

The killing, as I said, is far from ingenious and the detection suitably uninspired, but the tale itself gains a certain verisimilitude from its own mediocrity. This is murder as it’s really done, by the kind of people who really do it, and if the singer is not particularly skillful, the song is like a familiar folk ballad heard and never forgotten.

Bibliographic Note: This is the only entry for the author in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

Fri 19 Jun 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

DOUGLAS PRESTON & LINCOLN CHILD – The Cabinet of Curiosities. Grand Central Publishing, hardcover, June 2002; paperback: June 2003.

One in a series of novels by the co-authors, this features Pendergast, an enigmatic FBI agent, who is investigating old crimes that are suddenly made current by a series of murders in NYC that are either copycat killings or improbable crimes by the still surviving killer.

A newspaper reporter plays the role of the HIBK heroine (although he’s male), walking into situations that any sensible character would stay away from.

The bizarre nature of the crimes and the gradual unfolding of the killer’s identity and his rationale kept me reading but I ended the read with a feeling of dissatisfaction about the length of the book (629 pages) and lapses in narrative interest.

From Wikipedia: “Aloysius X. L. Pendergast, PhD is a fictional character appearing in novels by Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child. He first appeared as a supporting character in their first novel, Relic, and in its sequel Reliquary, before assuming the protagonist role in The Cabinet of Curiosities.”

Later novels:

Still Life with Crows (2003)

“The Diogenes Trilogy” —

Brimstone (2004) (Book One)

Dance of Death (2005) (Book Two)

The Book of the Dead (2006) (Book Three)

The Wheel of Darkness (2007)

Cemetery Dance (May 2009)

Fri 19 Jun 2009

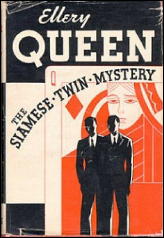

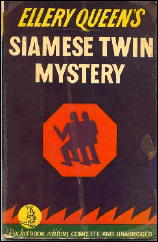

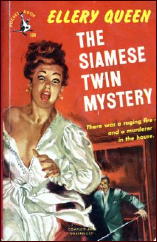

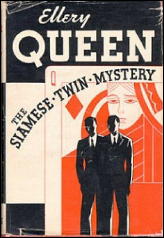

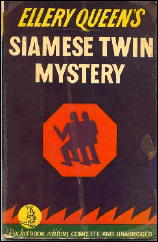

ELLERY QUEEN – The Siamese Twin Mystery.

Frederick A. Stokes, hardcover, October 1933. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and soft, including: Pocket Books #109, 1st printing, June 1941; Pocket #109, 10th printing, 1950; Pocket 6135, 12th printing, 1962; Signet T4086, 1970. (All shown.)

I don’t know how long I’ll last on this particular resolution, it not being New Year’s and all, but I’ve promised myself that if I can, I’ll go back and start re-reading some (not all) of the books I devoured while I was growing up.

This is the first one, and you can mark me as I go, although I probably won’t always be mapping and pointing the trail out along the way.

I don’t know when I read this one the first time — I didn’t even realize that you were allowed to have opinions about books and movies until I was in junior high — and I really thought about keeping records of what I read until 1970 or so.

And all I remember from the first reading of The Siamese Twin Mystery is the fire that drives Ellery and his dad, Inspector Queen, farther and farther up a mountain, flames licking at their tires most of the way.

Ellery was driving his Duesenberg, a model of car the name of which thrilled me in itself, and one so old that my spell-checker doesn’t even recognize it. The rest of the story was a blank, though. I didn’t remember a thing.

J. J. McC.’s foreword states the locale as Arrow Mountain, a peak in the Tepee range, which Google says is in Wyoming, perhaps extending as far south as Utah, but most definitely “in the heart of the ancient Indian country.”

There at the top of the mountain, with no route to safety open to them, they take refuge in (guess what) an isolated pile of a mansion in which (you guessed) a murder is about to take place, and in fact, eventually, two.

And not only is this an “isolated county manor” sort of story, but there are two dying messages involved — both in the form of torn playing cards found in the hands of each of the victims.

Bizarre circumstances, gruesome murders, eerie surroundings, this is a detective story that has it all, settingwise, even a pair of conjoined (Siamese) twins. (No surprise there.)

The actual detection, though, I thought was a trifle labored in comparison. The edition (a 3rd printing Pocket paperback from 1941) that I just finished did not even have a “Challenge to the Reader.”

Not that I have ever been up to the challenge of one of those, but for an Ellery Queen yarn, the explanation at the end made me think I might have gotten this one.

Well, the solution was clever enough, but I would have been close. Or I might have, I’m sure, if I’d thought about it. Ellery Queen’s solution are always obvious. Afterward.

There is a good legal question that arose at one point — and don’t take my bringing this up as my in any way letting slip the identity of the killer(s) — but if one of the Siamese twins had done it, how could he have been punished, without punishing the (possibly innocent) other?

This is a question I remember reading about somewhere before. Was there another tale, short story or novel, by another author perhaps, where the question also arose, or is one of the other things I remember from this mystery — besides the Duesenberg working its way up the mountain, that is?

PostScript. Got a favorite cover among this choice of five? Is there one that stands out for you and would make you want to buy the book as soon as you saw it? At cover price? There’s one for me, that’s for sure.

Fri 19 Jun 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

ADRIANNE BYRD – If You Dare. Harper Torch, paperback original; 1st printing, August 2004.

If there’s one kind of caper novel that I like to read, it’s one that takes place in the world of art. I’m not sure why, as the kinds of social circles the protagonists in such novels travel in are those which are way above my head. Or is that the attraction?

Blue Smoke and Murder, by Elizabeth Lowell, which I reviewed here not too long ago, was one such novel, and If You Dare is another. Or I thought it was when I bought it, almost five years ago, and again when I finally read it, sometime last week.

Billed as a Romantic Suspense novel, it turned out to be more highly oriented toward the Romantic end of the scale, and Steamy Romance at that, then it did the Suspense portion of the billing.

Damien Black is one half of the tango – he’s a professional art thief – and the unbelievably beautiful Angel Lafonte is the other – she’s the new director at an Atlanta museum, although he does not know that when he switches cell phones on her at a gathering where first they meet, and he’s willing to turn down the job he was hired for (steal from her new place of work) when he does.

It’s an interesting way to make sure you meet a lady again, that’s for sure, and the relationship between them heats up rapidly from there, with all of the usual complications. But in spite of all the plans, all of the hints and all of the talk, there is only one art theft that takes place, and that’s offstage, and we never get to see any of the actual operation itself.

And that’s what I was waiting for – and didn’t get – but according to those who reviewed If You Dare on Amazon, Ms. Byrd certainly delivered the goods in terms of what her real audience was looking for. Did I say Steamy Romance?

There are a couple or three decent twists in the storyline, but while the author’s readers having been asking for a sequel (there hasn’t been one), I didn’t find anything solid enough in this effervescently light souffle to tempt me back – not without checking the merchandise more thoroughly next time.

Thu 18 Jun 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

A REVIEW BY FRANCIS M. NEVINS, JR.

JAMES ELLROY – Suicide Hill. Mysterious Press, hardcover, 1986; paperback, April 1987. Reprinted in hardcover with Blood on the Moon and Because the Night as L. A. Noir, Warner, 1998. Trade paperback reprint: Vintage, 2006.

– Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.

Readers and moviegoers of the nineteen forties and fifties didn’t know it at the time, but they were living through the first wave of the harsh, moody, downbeat suspense novels and films we now describe as noir.

Since around 1970 we’ve been battered by a second wave of noir in print and on the screen: Joseph Wambaugh, George V. Higgins, Elmore Leonard, James Crumley, Dirty Harry, The French Connection, Death Wish, Chinatown, Taxi Driver, Body Double — only this time the imagery is in color, not black-and-white, the sex and violence are graphic, not poetic, and the sense of sleaze is overpowering.

For better or worse, it’s the books and films of the neo-noir configuration that most vividly shape our perception of American urban life today.

James Ellroy is part of that configuration. He was born in 1948 and marked forever at age ten when his mother was strangled to death by a man she’d picked up in a bar. He drifted into the hippie-druggie subculture of the Vietnam years.

“From ’65 to ’77,” he says, “I lived mostly on the streets, flopping out in parks, with about fifty arrests for drunk, trespassing, shoplifting, disturbing the peace, and other Mickey Mouse, booze-related misdemeanors. I imagine I did a total of about six months’ county jail time.

“I almost croaked from a series of booze- and dope-related maladies early in ’77. Realizing that it was live or die, I opted for life. I’ve been sober since August of ’77.”

He began writing a year or two later. Suicide Hill is his fifth novel in as many years and the third of his police procedurals featuring L.A.P.D. detective sergeant Lloyd Hopkins, Los Angeles’ version of Dirty Harry.

The Hopkins books are contrapuntally structured, with the alternation of perpetrator-cop-perpetrator-cop chapters borrowed from Wambaugh’s 1974 classic, The Onion Field, and are punctuated with blood orgies borrowed from neo-noir movie directors like Brian De Palma.

By Ellroy’s standards the first half of Suicide Hill is quiet and almost sedate, introducing the sleaze ball cast — a white psycho, a Chicano psycho, the Chicano’s weak-willed kid brother, the coked-out porn video star by whom the white psycho is obsessed, a call girl with a master’s in economics and a habit of reading George Gilder’s capitalist manifestos between tricks — and setting us up for confrontations between each of these characters and Crazy Lloyd Hopkins.

The blood and brains flow in earnest during the book’s second half, with five gruesome killings between pages 149 and 168 alone, as Hopkins comes closer and closer to the showdown which, for weird reasons of his own, Ellroy never lets happen.

Crazy Lloyd is a walking time-bomb, clearly just as sick as the pervs and perps he deals with. He routinely commits burglary to obtain evidence and perjury to get convictions. He fantasizes maiming the people he hates, such as a left-wing lawyer or his estranged wife’s new lover, and every so often he makes good on his dreams.

Ellroy draws all sorts of parallelisms between cops and creeps, but at the same time he wants us to accept Hopkins as a Jesus of the gutters, the way Wambaugh portrays his own police heroes. It’s one of Suicide Hill‘s many weaknesses that Ellroy never fuses the two sides of his protagonist’s character into a unity.

There are other problems, too: key scenes that are nearly incomprehensible, slipshod construction in spots, constant grammatical flubs that betray the white heat in which the book was written. And yet with all its faults this book has power. Ellroy is a master of the single most crucial neo-noir skill: he can make the nightworld of sleaze and street monsters come alive on the page.

At one point he has a character “wondering if the world was nothing but wimps, pimps, psychos and sex fiends.”

For Ellroy, child of violence and the city, the answer is Yes, and so far he has not conjured up an effective redeemer. If you can stand the relentless assault, on every level from physical butchery to sex abuse to four-, ten-, and twelve-letter words to racist humor, this is a perversely fascinating evocation of a world gone mad.

Bibliographic Update: The three novels included in L. A. Noir (see above), were the only appearances of Sgt. Lloyd Hopkins in print.

« Previous Page — Next Page »