August 2009

Monthly Archive

Sun 16 Aug 2009

STRANGE INTERLUDE. MGM, 1932. Norma Shearer, Clark Gable, Alexander Kirkland, Ralph Morgan, Robert Young, May Robson, Maureen O’Sullivan. Based on the play by Eugene O’Neill. Directed by Robert Z. Leonard (uncredited).

On stage, Strange Interlude was a long experimental play (four and a half hours with a dinner break) that won the 1928 Pulitzer Prize for drama. While the film was cut down to a manageable 110 minutes or so, the experiment of stopping the action and allowing the actors to voice what they were really thinking was carried over to the movie.

It didn’t work then, and it works even less (to a modern audience) now. Using voiceovers while the action stops and the actors try to match facial expressions to what the audience is hearing takes a LOT of getting used to. In these awkward moments, only Clark Gable seems able to deliver his lines in a natural and unforced manner, and that may be in part because he has fewer of them than any of the others.

While certainly abbreviated from the stage version, and abundantly censored in the process, there still remains much in this movie that wouldn’t have passed the provisions of the Hollywood Code that came along a couple of years later. In order to maintain her husband’s sanity (Alexander Kirkland), a woman (Norma Shearer) has an affair (and a child) with another man (Clark Gable) while still in love with a man who died in combat. To complete this five-sided romantic quadrilateral, a fusty old friend of her father’s (Ralph Morgan) is also in love with her but due to his strong ties to his mother, he is unable to tell her.

Her husband assumes the child (later to become Robert Young) to be his, but the strain of keeping the secret from him over the years wears and tears at the relationship between all of them, including the child himself, who for reasons he himself cannot easily explain, hates his “Uncle Ned.”

Mildly fascinating, overall, and as entertaining as a slow motion disaster set in motion by characters who are too weak to prevent it, but at least I now know which play it was that Groucho Marx was parodying in Animal Crackers (1930).

Sat 15 Aug 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

THE PRINCESS COMES ACROSS. 1936. Carol Lombard, Fred MacMurray, Douglas Dumbrille, Alison Skipworth, William Frawley, Sig Ruman, Porter Hall, Misha Auer. Screen story: Philip MacDonald, based on the novel The Duchess by Louis Lucien Rogger. (The latter may not exist in book form.) Director: William K. Howard.

Why they insisted on putting Carol Lombard in dramas is one of the great unexplained mysteries of Hollywood. She was born for screwball comedy, and graces some of the highpoints of the genre from Hawks’ Twentieth Century to Wellman’s Nothing Sacred, to the divine Lubitsch’s To Be Or Not To Be.

The Princess Comes Across isn’t quite in that illustrious company, but it’s close. The title alone is worth the price of admission.

Lombard is a would-be actress, Wanda Nash of Brooklyn, who went to Europe and got nowhere. She plans to cash in and hit New York big, though, by pretending to be a mysterious princess, Olga of Sweden, a Garbo-like figure sure to have the press in a frenzy by the time she hits New York.

What she hadn’t counted on was a romantic bandleader in the person of Fred MacMurray as King Mantell, and murder on the ship home. The result is a delightful comedy-mystery that sometimes gets lost among the surfeit of films in that genre from the same era.

Lombard made several films with MacMurray, and allegedly complained she wasn’t getting bigger stars as leading men, but the two are a good team, and if Fred was still a fairly minor leading man at this time, he wasn’t that far off from the films that would propel his career to major star status.

He has an easy-to-take quality that made him ideal for these roles that could have been either dull or strident in lesser hands. MacMurray manages to hit all the right notes, and compliments Lombard as well as bigger name leads like Cary Grant, John Barrymore, or her husband Clark Gable. He was one if the stalwarts of the screwball comedy genre in his own light.

The voyage is a hardly a vacation for anyone. There’s a blackmailer on board targeting Wanda and others, a killer who has taken the identity of one of the other passengers, and to add insult to injury, a convention of international detectives headed for New York.

Poor Wanda couldn’t have picked a worst boat for her trip. Then too she is falling for bandleader MacMurray, the last thing she needs in her life — a musician.

Of course with a mix like that, it’s only a matter of time until a body shows up and sets those nosy professional sleuths to sleuthing, and when their attention turns to Princess Wanda and King Mantell, they have no choice but to turn detective themselves to unveil the real blackmailer and killer.

Dumbrille and Ruman are among the police officers, Inspector Lorel and Steindorf. The set-up reminded me a little of C. Daly King’s novel Obelists at Sea, in which a convention of psychiatrists on a cruise all play detective while New York police Captain Michael Lord keeps his silence and tracks down the killer.

Like all good screwball comedies, the lines flow fast and furious, and the mystery is played for laughs, but with some genuinely spooky moments at night in the inevitable fog as Lombard tries to elude the killer.

Everyone is at the top of their form, and despite all a list of six screenwriters (four credited, two not, including J. B. Priestley), the script holds together extremely well, thanks to Philip MacDonald’s succinct adaptation of Rogger’s novel. (If you ever wondered exactly what the screen story was in relation to the screenplay, this is a good example where a strong story holds together all the disparate contributions of an army of screenwriters.)

We can be fairy certain it is MacDonald who keeps the mystery element in focus, while the comedy spins off of it. That said, I’d love to know what British novelist J. B. Priestley’s contribution was. He was no stranger to mystery and suspense or comedy in books or plays.

The comedy mystery was a specialty of this era: The Thin Man, Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back, The Mad Miss Manton, Arsenic and Old Lace, Whistling in the Dark, Slightly Larcenous, Grand Central Murder to name just a few, and it mixes well with the screwball school.

The high point was likely W. S. Van Dyke’s It’s A Wonderful World and George Marshall’s antic Murder, He Says, but Princess is no slouch, and Lombard and MacMurray are both genuinely attractive and believable.

Somehow this one has been neglected, but it doesn’t deserve that fate. It’s one of the brightest moments of the comedy mystery film at a time when these were being made with all the skills the studio system could bring to bear. The Princess Comes Across, and delivers, a jewel of a comedy mystery.

Sat 15 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

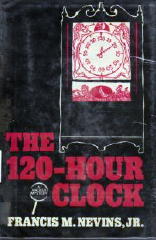

FRANCIS M. NEVINS, JR. – The 120-Hour Clock.

Walker, hardcover, 1986. Paperback reprints: Penguin, 1987; iUniverse, 2000.

One of the last mysteries published in 1986, The 120-Hour Clock by Francis M. Nevins, Jr., turned out to be one of the most enjoyable. Nevins has abandoned (except for a cameo appearance) his previous series sleuth, Loren Mensing, in favor of an extraordinary con man, Milo Turner, whose life and happiness depend upon his solving a murder.

The first chapter is an absolute grabber, beginning with a paragraph from Turner’s notebook in which he sounds the way Cornell Woolrich might have if he were reflecting on his career as a con man, instead of as a writer. After that we ride the Milonic roller coaster, mostly through New York and St. Louis, a world which includes Schultz’s Human Supermarket and Lafferty’s Identity Bazaar. .

Nevins operates on two levels. First, his book is a big-caper novel and practically a treatise on the scam, though its pace is far from scholarly. Using verbs the way Nevins does (purists may blanch), I can say I page-turned compulsively. Yet Nevins evokes considerable poignancy from his character, and, incidentally, he writes excellent love scenes, several with a nicely erotic touch.

If you’ve heard that Walker only publishes “cozy” books, disenchant yourself of that notion. The sex and the language are strong here, but they are appropriate; nothing is gratuitous.

The mystery reader of the future, say in the twenty-second century, can learn a great deal about how we lived in the latter half of this century from The 120-Hour Clock. There are scenes in large motels that perfectly capture how it is to spend time there.

In another scene, Turner and a woman he loves walk through Manhattan: “I linked my arm in hers as we trod the empty streets, talking in whispers so we wouldn’t wake the bag people sleeping on the steam vents.”

I’m not sure I believe all of this book, especially the ease with which Turner establishes new identities. I’m not ever sure I was supposed to. After all, Nevins is really in the same field as Turner, who says he’s “in the business of giving apparent reality to what doesn’t exist.” Both are highly successful at their professions.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.

Fri 14 Aug 2009

CIRCUS. Columbia, 2000. John Hannah, Famke Janssen, Brian Conley, Peter Stormare, Fred Ward, Eddie Izzard, Amanda Donohoe. Directed by Rob Walker.

There’s plenty of split opinion to go around on this movie, but to get mine out of the way first, me, I liked it. For the most part, the dissenters fall into two camps: first, those who couldn’t follow the plot line and gave up, and secondly, those who found it inferior to a number of other similar movies of the British gangster persuasion that came out around the same time: Snatch and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, to name two.

Not so coincidentally, both of these were directed by Guy Ritchie, and as to the latter objection, my opinion may be biased because I’ve yet to see either one.

But as for the complicated twists and turns of the plot: I loved them! Compared to a movie like Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round (reviewed here) in which the story line is straight as a string, with the mildest of zingers at the end, Circus is absolutely dynamite.

One never knows (until the next scene) who is in cahoots with whom, and not even with a scorecard can you even tell which players are on which team.

It would take several watchings before I’d feel totally confident that I’d have the story completely in my grasp, so that I could relay them on to you, and even then it might not even be possible. I’ll do my best, but I won’t go into detail, and of course you wouldn’t want me to anyway. (You’d hate me tomorrow if I did.)

In any case, here goes: a con artist couple named Leo and Lilly (John Hannah and Famke Janssen) are planning one last final scam, but unknown to them a brutal crime lord named Bruno (Brian Conley) has plans of his own, targeting Leo with a blackmail scheme that’s built around hiring him as a hit man to kill a woman named Gloria (Amanda Donohue) who’s already on Leo’s team, or has Lilly been bending Bruno’s ear so that she’s really working for him, or did I just make that up? In the meantime Leo’s bookie Troy (Eddie Izzard) is after him for some bad bets that he made and he wants to get paid, and can Leo actually trust Lilly? Bruno’s accountant Julius (Peter Stormare) is in on the blackmail scheme, but is he working for Bruno, for Leo, for Lilly, or himself, or is he only a poor schnook who’s being taken advantage of by all three? (Is Gloria really his wife, or is she only another pawn, or does she have a mind of her own?)

Once again, please keep in mind that some or all of the above is true. Would I lie to you? Yes, I would.

A complicated story like this could be a huge flop easily if the actors involved weren’t involved, and believe me, they are. No phoned-in roles in this movie. John Hannah you might remember as the later Inspector Rebus in that series, and Famke Janssen is even more memorable as Jean Gray in the “X-Men” extravaganzas. They make a terrific pair, whether working together in this movie, or not, when they are even better.

Fri 14 Aug 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Karol Kay Hope:

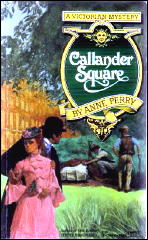

ANNE PERRY – Callander Square. St. Martin’s, hardcover, 1980. Reprint paperback: Fawcett Crest, 1981. Reprinted many times since.

Anne Perry’s books featuring London police inspector Thomas Pitt are called “Victorian mysteries.” One look at the covers of the paperback editions would lead the reader to believe they are just more of what has been called the “Gasp in the Grass” genre — the kind of stories that find the virginal heroine crawling at least once across the grassy slopes of a Victorian mansion in the moonlight.

Not so. Perry has very cleverly portrayed British Victorian society with a sharp eye for its particular brand of social deceit. She is especially skilled at making the reader realize the almost unbelievable subjugation of women in those days, and if one ever wonders why women began to rebel against social constriction at the turn of the twentieth century, these books will clear up that mystery, too.

Detective Thomas Pitt is a working-class hero in the extraordinary position of being called upon periodically to blow the cover of the English aristocracy. Being a policeman, he can exercise certain influence; if any blustering old gent attempts to order him out of the Morning Room, Pitt can threaten a search warrant.

He rarely needs to resort to such tactics, however, because he gets inside help from his charming wife, Charlotte, who stepped out of her upper-class world to marry him. She is an honest and enthusiastic woman whose family despairs of her insistence on following her own inchnations (although most of the women she grew up with admire her courage).

And she is invaluable to Pitt, since most of his cases involve his exposing the passion beneath the icy breast of the upper classes. Pitt analyzes the facts with cool logic, while Charlotte uses her family connections to pick up pertinent gossip over tea and crumpets.

In Callander Square, gardeners have inadvertently dug up the corpses of two newbom babies in the square of one of the most affluent suburbs of London. The neighborhood residents, while forced to admit the monstrosity of the deaths, simply chalk them up to the irnrnorality of some servant girl who “let herself” be molested — probably by a footman, perhaps the master of the house; gentlemen always dally with the servant girls “just for a spot of fun.”

It is too bad, they concede, that the girl was stupid enough to get herself into such a mess — but then, what can one expect from the working class anyway?

Of course, those babies never belonged to a servant girl, and it is Pitt’s job to expose the enormous hypocrisy of the self-righteous elite — as well as two murderers, a blackmailer, and a gentleman drunk. This is an excellent novel that says a great deal about social pretension and the harm it can do.

Other highly recommended books in this series are The Cater Street Hangman (1979), Paragon Walk (1981), Resurrection Row (1981), Rutland Place (1983), and Bluegate Fields (1984).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 14 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

ANNE PERRY – Southampton Row. Ballantine; reprint paperback, Feb 2003. Hardcover edition: Ballantine, February 2002.

I probably haven’t thought enough about this yet, so there are probably any number of exceptions I’m not thinking of right now. But it’s treacherous ground for detective stories to get into, isn’t it, when the case to be solved in one novel is nothing more than a continuation of that begun (and not finished) in another?

Thomas Pitt supposedly thwarted Charles Voisey, the villain in The Whitechapel Conspiracy, the book in the series before this one, and here he is, acting up again. It doesn’t feel right. Detective novels are supposed to have some sort of closure, aren’t they?

Or perhaps I should take it back. Sherlock Holmes had his nemesis in Professor Moriarty, Bulldog Drummond had to battle Carl Peterson for several adventures, and Sax Rohmer’s Nayland Smith was constantly dueling if not outwitting Fu Manchu, and it obviously didn’t hurt the popularity of any one of those series.

But — as far as I can recall, and you tell me if I’m wrong — each of Holmes’ cases was self-contained, and except for the escape of the villain at the end, each of the Drummond and Fu Manchu books tied up the loose ends, and this one of Anne Perry’s, at least, doesn’t. At the book’s end, we still don’t know who the other hidden adversary is, an alienated member of the Voisey’s Inner Circle? And/or is he one of Pitt’s superiors? Could the corruption reach that high?

Epic science fiction sagas seem to come in trilogies — rightly or wrongly, blame it on Tolkien? — but it’s a little disconcerting to discover it in detective fiction. I’m relatively new to Perry’s work in general. Her stories of the Thomas and Charlotte Pitt seem to make up one long, extended Victorian drama, and you could say the same about the William Monk books as well. Which is all well and good, and Perry’s work is very popular. I understand the attraction, but when there’s no resolution to the mystery end of things, I (speaking for myself) start to feel uneasy.

In the case at hand — to get back to the review in progress — it takes a while for an actual murder to occur for Pitt to solve, that of a medium who may also be a blackmailer. Her death may also involve Voisey, and his attempt to run for Parliament.

Before that, and even afterward, there is a large amount of 19th century British politics to be expounded upon, and arguments about social justice and Home Rule for Ireland, either by the candidates themselves, or their wives. You may or may not find it all very interesting, but I got the strong impression that this is the story that Perry really wanted to tell, and it goes without saying (doesn’t it?) zeal and enthusiasm does matter.

As for the mystery, I noticed small glitches in the plot here and there. And while Anne Perry’s narrative technique often consists of characters mentally asking themselves all manner of questions, the questions I wanted to ask were almost never among them.

Charlotte has only a minor role this time. In a melodramatic finish Thomas solves the murder, but if he has the goods on Voisey on another matter — “a complicated scheme of personal revenge” — why does he let him go? I’m badly fuddled. It didn’t help to go back and read certain passages again. In fact I think it made matters worse. Befuddled, therefore, I remain, and bodaciously bemused.

[UPDATE] 08-14-09. Before reprinting this review (which may not have actually appeared anywhere else until now), I confess I looked at the comments posted on Amazon, and I discovered that I was not alone in being put off balance by coming in at the middle and not having read the previous book in what’s now apparently a small “arc” in the overall Pitt series.

It didn’t bother regular readers of the series, however, of which there are many. I’ve read (but not reviewed) only one other of Thomas and Charlotte Pitt’s adventures, the title of which I no longer recall.

Earlier on this blog, though, you can read my comments here on Funeral in Blue, a case for William Monk, another book which, unfortunately, I also found disappointing.

Fri 14 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

SHERIDAN HAY – The Secret of Lost Things.

Doubleday, hardcover, March 2007. Trade paperback: Anchor, March 2008.

After her mother dies, Rosemary Savage, with the financial help of her mother’s best friend, moves to New York City, and soon finds a job at the Arcade, a mammoth used bookstore (clearly inspired by The Strand), where she hopes, as she puts it, to “call herself into being.”

This coming-of-age novel will delight any bibliophile, but it should capture the interest of mystery lovers as Rosemary becomes enmeshed in the intrigue that surrounds the discovery of a lost Herman Melville manuscript.

Still, what will probably finally linger in my memory are the incisively etched portraits of the peculiar staff of the Arcade and the portrayal of the store as a mysterious entity inhabiting a space seemingly detached from the world outside its walls.

It drew me in so completely that, given the chance to return, I would abandon the work-a-day world without a second thought.

Thu 13 Aug 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAN STUMPF:

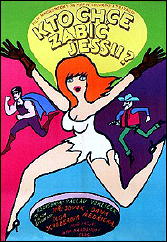

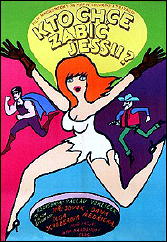

WHO WANTS TO KILL JESSIE? 1966. Originally released in Czechoslovakia as Kto chce zabíc Jessii? Director: Vaclav Vorlicek.

Despite the title, Who Wants To Kill Jessie (1966) is not a murder mystery, but a Czechoslovakian pop-art sci-fi satire (you know the type) made the same year as Alphaville and sharing many of that film’s fetishes for pop culture and politics.

An eminent (and rather dowdy) female scientist invents a serum designed to purge dreams of their unsettling elements, leading to happy, productive dreams (“No longer will people be allowed to dream anything they wish.”) and when she discovers her husband dreaming of a scantly-clad comic-strip heroine constantly menaced by a cowboy and a superhero, she purges his dream, only to have the characters materialize and begin a comic chase through their society.

A basic situation that could have led to facile clowning or heavy moralizing in lesser hands is handled here with charming slapdash panache and innocent energy delightful to watch.

Director Vaclav Vorlicek mixes sight gags and verbal humor (that survives the subtitling surprisingly well) with a deft touch and an obvious love of the comic-book culture he’s exploiting, and his players (whose names would mean nothing to you) convey a conflict of bureaucratic buffoonery and pulp-paper passion with that sincerity which is the essence of Comedy. A film that deserves a bigger reputation.

By the way, I know I said the cast names would mean nothing to you, but for the sake of Academic Correctness, I should add that the actress who plays the comic-strip-heroine starred in some enjoyably gaudy English-language films (like The Vengeance of She) and eventually found her way into the December 1969 issue of Playboy.

Just thought I’d mention it.

Editorial comment: And on the cover of the March 1964 issue. Worth mentioning, too, perhaps?

Thu 13 Aug 2009

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

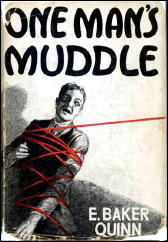

E. BAKER QUINN – One Man’s Muddle. Heinemann, UK, hardcover, 1936. Macmillan, US, hardcover, 1937.

Two years before Raymond Chandler introduced us to Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep (1939), E. Baker Quinn, a British writer, anticipated both his voice and his attempt to do something more serious with the detective novel with her first novel about former Scotland Yard sleuth James Strange, an accomplishment noted by critic James Sandoe in his famous list of notable hard-boiled writers.

When we first meet her sleuth James Strange, he has fled to a “… tu’penny ha’penny inn a hundred miles from nowhere,” to escape his past. But he knows it’s hopeless. “Do a bunk to the jungles of Africa and ten to one you’ll meet your mother-in-law’s char coming around the first bush …”

And for Strange it is much worse than his mother-in-law’s charwoman. He’s runs smack into the former Mrs. Boynton, now Mrs. Geoffrey Wharton, a former London snowbird, an addict, who knows all about Scotland Yard’s former bright young thing who has just completed four years in the pen for possession of illegal drugs.

I wondered if she would be stupid enough to lie. Burns was wrong. If we could see ourselves as others see us police blotters would be empty. For instance, she’d have made an attempt to douse the 400-watt light blazing in her eyes.

And of course Mrs. Wharton is promptly murdered, and Strange finds himself forced to help her husband cover up her past while trying to cover up his own and keep the police from finding the .32 caliber automatic hidden in his luggage, the gun he used in a manslaughter case he was acquitted in — but would rather not bring up again — and coincidentally, the same caliber Mrs. Wharton was shot with …

His attempts to keep his head above water push him deeper into the mess, and force him back to his ex-fiancee in London and to Ratchet, the partner who ratted on him and testified against him as King’s evidence.

That’s the set up for a novel that anticipates the style and voice of Chandler’s novels:

Well, I thought, the lad who wrote what a tangled web we weave certainly knew what he was talking about. From the night of Alice’s (Mrs. Wharton) death, when I made a bargain with Wharton to keep his secret if he kept mine, one thing had followed on another. Little pyramids pyramiding precariously and I was so involved now that when they crashed I’d find myself squarely on the bottom of the pile.

Before it is over Strange will solve the case, but find himself facing another two years in prison.

“I tank ay asked for it,” I said in a small Swedish accent, “ay been dom fool.”

In later books Strange gets out of prison and goes to work as a private eye with his despised ex-partner Ratchet. The voice continues in the Chandler vein.

Who Quinn was, and how she came to discover a voice and subject matter so close to Chandler is a mystery in itself. But her books are worth discovering and reading, and Strange a curious compliment to Marlowe and his world.

Here are a few samples of Quinn and Strange:

I gave a flawless imitation of a man looking at a packet.

“It’s a curious thing, Mr. Strange,” he said, but I never go to the cinema.”

“I never go to America,” I said, “but I know what Roosevelt looks like.”

“Anything I tell that old bargepole,” I said, “you can cook three minutes and throw away.”

If one-eighth of the publicans in England began telling all they knew, divorce and civil courts would take over the nation.

Curious how the saving of great honour usually involves the destruction of several small honours. Like the nobleman’s son who saved the families honour by not marrying the dairymaid.

He made me think of Luther and Savonarola and Reformations, possibly because he had what I call the Righteous Eye. Believe me I’m an authority on the Righteous Eye. The judge who sent me up had it.

A thin chill pimpled all over me.

She gave me a rake over then, twice the voltage of mine.

I wondered irritably how anything as peaceful as the village could be so damn unpeaceful.

The cows gave me the same kind of look coming home with an old lady in my arms and a dripping child on my heels as they gave me going out and I thought it must be wonderful to be beyond surprise like that.

Tonight I’d ride the old nightmare, I’d cease to walk erect and unafraid. Four years of dreams, I thought, bitterly, and just a handful of hours to kill the dream …

One Man’s Muddle and its sequels are an interesting look at a Marlowe that might have been, one of those curious side roads that sometime run parallel to a more successful track. And well worth reading and discovering as first rate mysteries by a writer who deserved more recognition than she got.

Bibliographic data: [From the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin]

QUINN, E(LEANOR) BAKER

One Man’s Muddle (n.) Heinemann 1936. Macmillan, 1937. [James Strange]

The Dead Harm No One (n.) Heinemann 1938. (**)

Death Is a Restless Sleeper (n.) Heinemann 1940. Mystery House, 1941. [James Strange]

(**) While it seems likely that he is, it is not known whether James Strange is in this book or not.

Thu 13 Aug 2009

Peeking ahead at next November’s schedule, I found a bonanza of “Falcon” movies coming up on Turner Classic Movies. Synchronize your calendars!

Friday November 20

6:00 AM Gay Falcon, The (1942)

A society sleuth tries to break up an insurance scam. Cast: George Sanders, Wendy Barrie, Gladys Cooper. Dir: Irving Reis. BW-67 mins, TV-G, CC

7:15 AM Date With The Falcon, A (1941)

The gentleman detective postpones his wedding to find a cache of stolen diamonds. Cast: George Sanders, Wendy Barrie, James Gleason. Dir: Irving Reis. BW-63 mins, TV-G

8:30 AM Falcon Takes Over, The (1942)

A society sleuth and a lady reporter try to track down a murderous thug’s lost girlfriend. Cast: George Sanders, Lynn Bari, Ward Bond. Dir: Irving Reis. BW-63 mins, TV-G

9:45 AM Falcon’s Brother, The (1942)

A gentlemanly detective calls on his brother to help him stop the Nazis from assassinating a key diplomat. Cast: George Sanders, Tom Conway, Jane Randolph. Dir: Stanley Logan. BW-63 mins, TV-G. [Screenplay by Craig Rice and Stuart Palmer.]

11:00 AM Falcon Strikes Back, The (1943)

A society sleuth is framed for murder by criminals running a war-bond racket. Cast: Tom Conway, Harriet Hilliard, Edgar Kennedy. Dir: Edward Dmytryk. BW-66 mins, TV-G

12:15 PM Falcon In Danger, The (1943)

A society sleuth tracks a lost plane carrying $100,000. Cast: Tom Conway, Jean Brooks, Elaine Shepard. Dir: William Clemens. BW-70 mins, TV-G

1:30 PM Falcon And The Co-Eds, The (1944)

A society sleuth investigates murder at a girls’ school. Cast: Tom Conway, Jean Brooks, Isabel Jewell. Dir: William Clemens. BW-68 mins, TV-G

2:45 PM Falcon Out West, The (1944)

A society sleuth turns cowboy to investigate a Texas murder. Cast: Tom Conway, Carole Gallagher, Barbara Hale. Dir: William Clemens. BW-64 mins.

4:00 PM Falcon In Mexico, The (1944)

A society sleuth travels South of the border to investigate an art dealer’s murder. Cast: Tom Conway, Mona Maris, Martha MacVicar. Dir: William Berke. BW-70 mins, TV-G

5:15 PM Falcon In Hollywood, The (1944)

A society sleuth tours the movie capital, where he uncovers an actor’s murder. Cast: Tom Conway, Barbara Hale, Sheldon Leonard. Dir: Gordon Douglas. BW-67 mins, TV-G, CC

6:30 PM Falcon In San Francisco, The (1945)

A society sleuth enlists a little girl’s help in nabbing a mob of silk smugglers. Cast: Tom Conway, Rita Corday, Sharyn Moffett. Dir: Joseph H. Lewis. BW-66 mins, TV-G.

—

These, of course, have played many times over on TCM, but if you’ve never seen or taped them before, here’s a great chance to obtain them all at once. There are two more in which Conway appeared, followed by three starring John Calvert. You may have to hunt a while on the collector’s market for some or all of these.

THE FALCON’S ALIBI. (1946, RKO) Tom Conway, Elisha Cook, Jr.

THE FALCON’S ADVENTURE. (1946, RKO) Tom Conway.

THE DEVIL’S CARGO. (1948, Film Classics) John Calvert, Rochelle Hudson, Roscoe Karns, Lyle Talbot, Tom Kennedy, Theodore Van Eltz, Paul Regan

APPOINTMENT WITH MURDER. (1948, Film Classics) John Calvert, Catherine Craig, Lyle Talbot, Jack Reitzzen, Peter Brocco

SEARCH FOR DANGER. (1949, Film Classics) John Calvert, Albert Dekker, Myrna Dell, Douglas Fowley, Ben Welden

« Previous Page — Next Page »