September 2009

Monthly Archive

Fri 18 Sep 2009

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

CAROLYN WELLS – The Gold Bag. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1911. Silent film: Edison, 1913, as The Mystery of West Sedgwick. Online text: here.

“Though a young detective, I am not entirely an inexperienced one, and I have several fairly successful investigations to my credit on the records of the Central Office. The Chief said to me one day: Burroughs, if there’s …”

The prolific American writer Carolyn Wells was mocked by Bill Pronzini in his entertaining book on “alternative” mystery classics (books so bad they’re good), Gun in Cheek, for having written an instructive tome on the craft of mystery fiction, The Technique of the Mystery Story (1913), and then seemingly failed to follow her good advice when composing her own mystery tales.

Wells’ second detective novel, The Gold Bag — which actually precedes The Technique of the Mystery Story by two years — illustrates Pronzini’s thesis. It might well have been titled The Leavenworth Case for Dummies.

Carolyn Wells was first drawn to reading mystery fiction in her mid-thirties when a neighbor lady came calling on Wells and her mother and read to them some of Anna Katharine Green’s latest detective novel, That Affair Next Door (1897) (Wells, by the way, suffered hearing loss as a child and wore a hearing aid throughout her life.)

Green had published a hugely popular mystery novel, The Leavenworth Case (1878) nearly twenty years earlier, and had settled into a comfortable career as a prolific crime writer.

Though I personally find it unreadable due to the stilted, melodramatic speech-making of its characters (particularly the two nieces), The Leavenworth Case is considered a seminal work of mystery fiction and is still taught today. Moreover, it does have a solid plot and is fascinating for being an early instance of so many Golden Age mystery tropes: the millionaire murdered in his mansion study/library, the retinue of suspicious servants, the beautiful niece (in this case two), the private secretary, the will.

Wells clearly was familiar with The Leavenworth Case, because The Gold Bag, her follow-up to her debut detective novel, The Clue (1909), obviously is modeled on Green’s famous tale.

In The Gold Bag there is a Watsonesque narrator figure, as there is The Leavenworth Case (in this case Burroughs, apparently a private detective — Wells is never clear on realistic detail like this). As in Leavenworth, this figure is called in to be involved in a murder investigation, this one in a wealthy town in New Jersey (probably, one suspects, quite like Wells’ own home town).

The case involves a millionaire murdered in his study, a retinue of suspicious servants, a beautiful niece, a private secretary and a will. (Sound familiar?) As in Leavenworth, a great deal of time is spent on the coroner’s inquest. As in Leavenworth, the Watsonesque figure becomes enamored with the beautiful niece suspected of the crime. Will true love prevail? What do you think?

Following Leavenworth by over thirty years, The Gold Bag is written in a sprightlier style and reads much more quickly. Where it falters is in providing an adequate puzzle. Wells’ putative Great Detective, Fleming Stone, appears briefly at the beginning of a 325 page novel, then returns in the last twenty pages to solve this case.

If this suggests to you problems with the solution, you are right. Most of the novel is devoted to Burroughs’ investigating various trails (including the trail of the gold bag of the title), all leading to different suspects, and all proving false. During virtually the whole novel, Burroughs, when not pining for the niece, is lamenting how the great Fleming Stone is not around to solve the case for him, until you just want to thrash him.

When Stone does show up he eliminates one suspect on the basis of deductions he had made some days ago about some shoes left out to be cleaned at a hotel, shoes that just happen to turn out to have been the shoes of this suspect!

“It is very astonishing that you should make those deductions from those shoes, and then come out here and meet the owner of those shoes,” pronounces another character. I’ll say!

Then Stone pulls the murderer, the only person left not suspected at some point in the novel, out of his hat, and the fool hysterically confesses his/her guilt and commits suicide with one of those convenient poison pellets Golden Age murderers always seem to have handy when the Great Detective points the Dread Accusing Finger at them.

This leaves one page for the author to pair off Young Love, and all ends happily ever after (except for the murderer, but readers will barely remember him even one page after his exit).

So, with disappointing detection, no clever murder mechanics, cardboard characters and no interesting descriptive writing, there is not much to recommend this one, except from a sociological standpoint.

It’s not really bad enough, either, to qualify as one of Pronzini’s alternative classics. Notably lacking here is the rather silly humor and situations found in many of Wells’ later detective novels.

There is still an air of unreality about the whole enterprise, however. The murdered man was a businessman of some sort, but we never learn anything about his business. A police investigator is briefly mentioned, but he does nothing. Indeed, it seems to be the view in the The Gold Bag that coroners and district attorneys rely exclusively on private investigators to conduct murder cases for them, without any involvement from the police.

One is left with the impression that Wells had a rather limited acquaintance with what might be termed “real life.” Granted, Golden Age novels often did not stress realism, but Wells’ novels seem to me too far removed from any semblance of it.

If they were clever Michael Innes-ian parodies of the form that would be one thing, but they don’t seem to be that either. So far they just seem to me mildly silly.

But, given their apparent popularity, they do show that there was a mystery fiction audience in the United States over the period Wells published mystery novels (1909-1942) that must have been far, far removed in taste from the celebrated hardboiled style.

Note: Curt hasreviewed another book by Carolyn Wells on this blog, Feathers Left Around, from 1923.

Thu 17 Sep 2009

LUIZ ALFREDO GARCIA-ROZA – The Silence of the Rain.

Picador, trade paperback; 1st printing, July 2003. Hardcover edition: Henry Holt and Co., July 2002.

This moody sort of detective novel was first published in Brazil and translated from the Portuguese, and I recommend it to you. It starts out in a mildly light-hearted fashion, as a mixup over a wealthy executive’s suicide in a parking garage — someone went off with the gun and the suicide note — leads Inspector Espinosa of Rio de Janeiro’s First Precinct into handling the case as though it were a murder.

(Not unlike Columbo of TV fame here in this country, we are privy to certain events that Espinosa is not, and even by the end of the case he is still running through endless speculations as to what actually happened.)

The mood becomes gradually edgier, though, until page 121, which is where the reader is forcibly confronted with the realization that this is no cozy, if not before. Reading mysteries taking place in other countries also makes you realize that the rules are often totally different. Here’s a quote from page 161:

I left thinking about the paradox: I trusted the information i could get from lowlife street gamblers but was wary of that same information in the hands of my fellow policemen. The worst was that I didn’t even know exactly how much I distrusted them, but one of the things I’d learned from a life on the force was not to confide in other officers.

And from page 238:

Espinosa called the precinct from the hospital No news. They kept reiterating that it was an isolated kidnapping, not related to the “normal kidnappings in the city.” Espinosa was stunned by the phrase: how could cops talk about “normal kidnappings”? Were there normal kidnappings and abnormal kidnappings?

Espinosa is, the dead man’s widow decides, a rare bird, a cultivated policeman. He is attracted to her. She is so wealthy she does not seem to notice. Espinosa is a reader of Dickens and Thomas De Quincey, is afflicted by loneliness and self-doubts, and he is also better than decent as a reader of character.

Besides an almost other-worldly atmosphere and surroundings, there are enough twists and turns of the plot to keep any detective story buff more than satisfied, even with the aforementioned Colombo-like prologue, with an ending I know I’ve never read before — I couldn’t possibly have forgotten a scene like this, and you won’t either.

And yes, the telling of tale does switch back and forth between first person and third. Just in case you were wondering.

— July 2003.

The Inspector Espinosa series —

1. The Silence of the Rain (Holt, hc, 2002; Picador, trade pb, 2003)

2. December Heat (Holt, hc, 2003; Picador, trade pb, 2004)

3. Southwesterly Wind (Holt, hc, 2004; Picador, trade pb, 2004)

4. A Window in Copacabana (Holt, hc, 2005; Picador, trade pb, 2006)

5. Pursuit (Holt, hc, 2006)

6. Blackout (Holt, hc, 2008; Picador, trade pb, 2009)

7. Alone in the Crowd (Holt, hc, 2009)

[UPDATE] 09-17-09. My local Borders store stopped carrying these after the first three or four. I hadn’t realized there were more in the series until now. I’ve also searched thoroughly, and there doesn’t seem to have been a softcover edition for #5 — why that should be, I certainly can’t tell you.

Thu 17 Sep 2009

More authors’ entries from Part 34 of the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. Most of these authors’ names are unfamiliar now, but if you take the time to read through their biographies, brief as they are, you’ll see how well known they were in their day.

BRITTON, KENNETH PHILLIPS. Poet, playwright, writer. Co-author (with Roy Hargrave, 1908- , q.v.) of one mystery play included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV.

HAPGOOD, HUTCHINS. 1869-1944. Born in Chicago. Add: educated at the University of Michigan, at Harvard, and in Berlin and Strasburg. Later a journalist and drama critic for the Chicago Evening Post; noted most as a social critic and an anarchist. Author of one novel included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. See below:

The Autobiography of a Thief. Duffield & Co., US, hc, 1903; Putnam, UK, 1904. Add setting: New York City. From an online New York Times review: “… a graphic and picturesque account of life in the under world.” [Text online.]

HARDING, JOHN WILLIAM. 1864-? Add biographical information: Born in London, England; educated there and in Paris. Later on editorial staff of New York Times; short story writer and playwright. Author of one novel included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. Note that his full middle name was used on this title:

A Conjurer of Phantoms. F. Tennyson Neely, US, hc, 1898. [An “elusive supernatural novel,” says one ABE bookseller.]

HARDY, ARTHUR SHERBURNE. 1847-1930. Add biographical information: Born in Andover, Massachusetts and educated in Boston, Switzerland and at West Point; Professor of Civil Engineering, Los Angeles College, and of mathematics at Dartmouth College, 1884-1893. Editor of Cosmopolitan magazine, 1893-95. Consul-General to Persia, 1897-1899; U.S. Minister to Greece, Romania and Serbia, 1899-1901, to Switzerland, 1901-1903, and to Spain, 1903-1905. Among other writings, the author of one detective novel and one story collection included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. Series character: Inspector Joly, who appears in the novel and six of the eleven short stories.

Diane and Her Friends. Houghton Mifflin, US, hc, 1914, hc. Story collection. Queen’s Quorum title.

No. 13, Rue du Bon Diable. Houghton Mifflin, US, hc, 1917.

HARGRAVE, ROY. 1908- . Add year of birth & biographical information: born in New York; actor, director and author. Co-author (with Kenneth Phillips Britton, q.v.) of one play included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV.

Houseparty. French, US, pb, 1930. [3-act play.] Add setting: Massachusetts; Academia (Williams College).

HARRADEN, BEATRICE. 1864-1935. Add biographical information: Born in Hampstead, London; member of several societies for social reform and women’s rights. Author of two novels included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. This is now the author’s complete entry:

Out of the Wreck I Rise. T. Nelson & Sons, UK, hc, 1912. Add US edition: Stokes, US, 1912; also add setting: England. Note: The title is a quote from Robert Browning. [Text online.]

Search Will Find It Out. Mills & Boon, UK, hc, 1928. Setting: England. Note: The title is a quote from Robert Herrick.

HARRISON, EDITH OGDEN. 1862-1955. Add year of birth and biographical information: Born Edith Ogden in New Orleans; in 1887 married Carter Henry Harrison, who served at least five terms as mayor of Chicago. Noted author of juvenile fiction, travel books and autobiographical works, plays and novels; contributor to Chicago Daily News. Author of two tales of the Royal Canadian Mounties listed in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. This is now the author’s complete entry:

The Lady of the Snows. McClurg, US, hc, 1912. Setting: Canada. Illustrations by J. Allen St. John. Add film: 1915; see synopsis here. [Text online.]

The Scarlet Riders. Chicago, IL: Seymour, US, hc, 1930. Setting: Saskatchewan, Canada. “Western adventure novel of train robbery and banditry.”

Thu 17 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini:

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Big Knockover. Edited and with an Introduction by Lillian Hellman. Random House, 1966. Paperback reprint: Dell, 1967, in two volumes: The Big Knockover and The Continental Op: More Stories from The Big Knockover. Also: Vintage V829, 1972.

Samuel Dashiell Hammett was the father of the American “hard-boiled” or realistic school of crime fiction.

As Raymond Chandler says in his famous essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” Hammett “wrote at first (and almost to the end) for people with a sharp, aggressive attitude to life. They were not afraid of the seamy side of things; they lived there. Violence did not dismay them; it was right down their street. Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not hand-wrought dueling pistols, curare and tropical fish. He put these people down on paper as they were, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used for these purposes.”

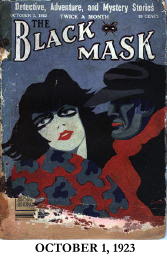

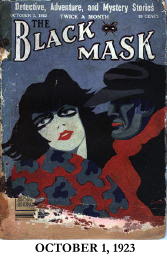

Hammett’s first published short story, “The Road Home,” appeared in the December 1922 issue of the pioneering pulp magazine Black Mask under the pseudonym Peter Collinson. The first “Continental Op” story was “Arson Plus,” also published as by Collinson, in the October 1, 1923, issue; the October 15 number contained “Crooked Souls,” another Op novelette and Hammett’s first appearance in the magazine under his own name. (“Arson Plus” was not the first fully realized hard-boiled private-eye story; that distinction belongs to “Knights of the Open Palm,” by Carroll John Daly, which predated the Op’s debut by four months, appearing in the June 1, 1923, issue of Black Mask.)

Two dozen Op stories followed over the ensuing eight years; the series ended with “Death and Company” in the November 1930 issue.

The Op — fat, fortyish, and the Continental Detective Agency’s toughest and shrewdest investigator — was based on a man named James Wright, assistant superintendent of the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Baltimore, for whom Hammett had worked. And his methods, if not his cases, are based on real private-investigative procedures of the period.

It was in these Op stories that Hammett honed his realistic style and plotting techniques, both of which would reach their zenith in The Maltese Falcon (1929).

The Big Knockover contains thirteen of the best Op stories, among them such hard-boiled classics as “The Gutting of Couffignal,” about an attempted hoodlum takeover of an island in San Francisco Bay, during which corpses pile up in alarming numbers and a terrific atmosphere of menace and suspense is maintained throughout; “Dead Yellow Women,” which has a San Francisco Chinatown setting and colorfully if unfortunately perpetuates the myth that a rabbit warren of secret passageways exists beneath the streets of that district; “Fly Paper,” in which the Op undertakes “a wandering daughter job,” with startling results; “Corkscrew,” a case that takes the Op to the Arizona desert in an expert blend of the detective story and the western; and “$106,000 Blood Money,” a novella in which the Op sets out to find the gang that robbed the Seaman’s National Bank of several million dollars, and does battle with perhaps his most ruthless antagonist.

Lillian Hellman’s introduction provides some interesting but manipulated and self-serving material on Hammett and his work.

This is a cornerstone book for any library of American detective fiction, and an absolute must-read for anyone interested in the origins of the hard-boiled crime story.

The Continental Op appears in several other collections, most of which were edited by Ellery Queen and published first in digest-size paperbacks by Jonathan Press and then in standard paperbacks by Dell; among these are The Continental Op (1945), The Return of the Continental Op (1945), Hammett Homicides (1946), Dead Yellow Women (1947), Nightmare Town (1948), The Creeping Siamese (1950), and Woman in the Dark (1951).

The most recent volume of Op stories, The Continental Op, a companion volume to The Big Knockover but edited and introduced by Stephen Marcus instead of Hellman, appeared in 1974.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Comment: Coming over the four days, spread out at a rate of one a day, will be reviews by Bill Pronzini and Mike Nevins of The Dain Curse, The Glass Key, The Maltese Falcon, and The Thin Man, all taken from 1001 Midnights.

Wed 16 Sep 2009

LAURAN PAINE – The Running Iron.

Five Star, hardcover; first edition, November 2000. Leisure, paperback reprint; 1st printing, April 2002.

Lauran Paine isn’t a household name, but over the past 50 years he’s been a small powerhouse in the world of traditional westerns. His overall output, including mysteries and romances, includes over 1000 books published, many only in England, under nearly 100 pseudonyms.

One difference between Paine and his younger contemporaries is that he’s lived closer to the time period he writes about, rather than learning about it second-hand. The characters in his stories are taciturn and close-mouthed. They don’t feel obliged to talk about what they’re thinking, what they’re doing or why. Newer writers seem to explain everything. Paine shows and often doesn’t tell.

In this story, after Old Joe Jessup dies, his ranch is left to May, his Indian wife, and his adopted son, Little Joe. A neighboring rancher wouldn’t mind adding the land to his own spread. Can one boy, an old woman, and an even more ancient hired hand manage to hold on without him?

In close conjunction to this, the army is called in to move a small tribe of Indians, May’s extended family, onto a reservation. In terms of action, there’s very little. Each chapter moves six inches forward, then five to ten inches back. The end result is a book that’s both frustrating and captivating.

— Reprinted from Durn Tootin’ #3, October 2003.

[UPDATE] 09-16-09. This review appeared for the first time in a newsletter for the Historical Novel Society soon after the hardcover came out, and before Lauran Paine died in 2001. As I noted above, I reprinted it later in my western fiction apazine, where I didn’t do any rewriting, nor have I now.

Some of the names Paine wrote under, besides his own, are (take a deep breath) John Armour, Reg Batchelor, Kenneth Bedford, Frank Bosworth, Mark Carrel, Robert Clarke, Richard Dana, J F Drexler, Troy Howard, Jared Ingersol, John Kilgore, Hunter Liggett, J K Lucas, and John Morgan.

I haven’t done any counting, so I don’t know if the list of titles is complete at either Web location — there certainly doesn’t seem to be over a few hundred at either one — but at least you can find partial bibliographies on Wikipedia and the Fantastic Fiction site, the latter with many covers.

Wed 16 Sep 2009

THREE GIRLS ABOUT TOWN. Columbia, 1941. Joan Blondell, Robert Benchley,, Binnie Barnes, Janet Blair, John Howard, Hugh O’Connell, Frank McGlynn Sr., Eric Blore. Director: Leigh Jason.

What this movie is, if I may be allowed to say so, is a screwball comedy that is not only not screwball, but for the most of its 75 minutes of running length, not even funny.

Robert Benchley always cracks me up, though, no matter what movie he’s in, and as Wilburforce Puddle, the manager of the hotel for which Joan Blondell and Binnie Barnes work, he’s no exception here. Even his name is funny.

Joan Blondell and Binnie Barnes (as Faith and Hope Banner) are hostesses for the hotel, which caters to conventions, but the wholesome kind. One wonders, though, what the local women’s civic league thinks they have been doing, marching in on the manager to deliver their complaints in person.

Puddle has other problems. There is a magicians’ convention that is just closing, and a morticians’ convention that is coming in, and never the co-mingling should meet. Not to mention the upstairs ballroom where a defense-oriented corporation and an angry employees union are waiting for a government mediator to arrive, and worst of all, a dead man in the room next to our two ladies.

Whose sister has just arrived, naturally named Charity (Janet Blair, in her debut film), who’s delinquent from the school where they’re sending her and a delinquent in more ways than that, the way she has eyes for Faith’s fiancé, who’s in the hotel covering the labor battle but who discovers that he has another story on his hands, if the body would ever stay in one place long enough for the police to do anything about it. (Charity also gets what’s coming to her at the end of the movie. Rather remarkably, too, that’s all I can say.)

Getting back to the main proceedings, also worth mentioning is the wandering Charlemagne, a drunken magician (Eric Blore) who interrupts the proceedings looking for his good friend Charlie wherever the laughs seem to be dying out — which is something like every five minutes.

It is hard to say what exactly goes wrong, that this movie isn’t more fun than it should be. Everyone tries hard, but it’s tough slogging when the jokes just aren’t as funny as whoever thought them up thought they were. Either that, or my taste in humor and theirs just don’t jibe.

Wed 16 Sep 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

LUCKY STAR. Fox Film Corp., 1929. Charles Farrell, Janet Gaynor, Guinn “Big Boy” Williams, Paul Fix, Hedwig Reicher, Gloria Grey, Hector V. Sarno. Scenario by Sonja Levien; photography by Chester Lyons and William Cooper Smith; art direction by Harry Oliver. (Originally part talkie, but the soundtrack has been lost.) Director: Frank Borzage. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

This was one of the films severely compromised by print quality. On its original release, the New York Times reviewer described a film in which “many of the scenes highly resemble etchings — dim portraits of aged shingle houses, with their shutters hanging askew,” and in which muted tones “play a large part.”

Although the print quality left most of these details to the viewer’s imagination, it was apparent that the sets were expressionistic, often angled so that the architecture appeared slightly askew, off-center.

It was clearly a studio (or a stage) set, a grim landscape with the houses widely separated and sparsely populated, a setting appropriate to the film’s minimalist drama, with the look of some remote European village rather than the American town it is supposed to represent.

Timothy Osborn (Charles Farrell) and Martin Wrenn (Guinn Williams) go off to war together and while Wrenn returns to pick up his life where he had left off, Osborn comes back as a cripple who lives by himself in a cottage where he takes on odd jobs to support himself.

Mary Tucker (Janet Gaynor) is the young girl they left behind, now a young woman to whom both men are attracted. Wrenn’s body may be untouched by the war, but his spirit is dark and violent, while Osborn’s bright spirit is undamaged by his experiences.

Mary’s mother, in a telling performance by Hedwig Reicher, wants a better life for her daughter and forbids her to visit Osborn, supporting the suit of Wrenn, who plans to take her away but whose intentions are anything but honorable.

This seems a much smaller film than Borzage’s earlier 7th Heaven and Street Angel, but the director’s handling of his actors is so sure that he makes the !miracles of the spirit he favors in his films believable and touching, even when the darkened print sabotages his intentions.

Wed 16 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Thin Man. Alfred A. Knopf, 1934. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including Pocket #196, 1942.

I read Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man back in High School, and I didn’t like it much because it wasn’t The Maltese Falcon. But just lately, some forty years later, I figured I’d give it another try.

I sort of wish I didn’t remember the movie (MGM, 1934) so well, or maybe that the film hadn’t been so faithful to the book. It would have been nice to come back to this fresh, not knowing the ending, just to see how well Hammett constructed this tricky mystery, a tale so well put together that one scarcely knows where to look among a cast of cleverly conceived (and, for the most part, sympathetically observed) suspects — or just what it is we’re looking for.

Is The Thin Man about the murder of Julia West or is it about the con game she was working on the missing Wynant? Is it concerned more with a missing-persons case, or with the kinky, incestuous Wynant family? Whatever the puzzle, it reads quite nicely, with a sense of humor that sneaks up on one very pleasantly indeed.

I might carp that Nick Charles, the narrator/detective, tells the story rather flatly, which contrasts a bit too sharply with the wise-cracks he and Nora keep throwing around in the dialogue. Compare this to the colorful narration Raymond Chandler gave to Philip Marlowe and you’ll see what I mean: Marlowe is a consistent smart-ass, but Nick Charles only gets colorful when he’s talking to the other characters.

But that, as I say, is just carping. The Thin Man has a reputation as a mystery classic, and I was happy to discover how richly it deserves it.

By the way, the movie version, first in a long line of “Thin Man” films, is quite faithful to the book, and generally well thought-of, but it doesn’t hold up quite as well, due largely to a clunky and obvious-red-herring opening sequence (not in the novel) that looks to have been tacked on rather hastily, and someone’s insistence on giving everyone in the cast a Guilty Close-Up.

You know the kind of thing I mean: someone makes a remark or picks up a clue and we cut to a shot of Maureen O’Sullivan or Cesar Romero looking like their pants fell down. It’s the sort of thing they were doing in the Charlie Chan films over at Fox, and it seems embarrassingly out of place in a film that’s mostly fast-moving and sophisticated.

Tue 15 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Susan Dunlap:

RUTH RENDELL – Speaker of Mandarin. Pantheon, US, hardcover, 1983. UK edition: Hutchinson, hc, 1983. Paperback reprint: Ballantine, 1984.

This is the twelfth novel featuring Detective Chief Inspector Reginald Wexford and his subordinate, Mike Burden, of the English village of Kingsmarkham. By now they have developed into a competent, professional, and thoughtful pair who work comfortably together.

It is their very decency and stability that give them the ability to spot the aberrations of the guilty. People trust the middle-aged, overweight Wexford, but frequently they underrate him. Wexford notes and makes use of this. The reader, too, can trust Wexford, accept his judgments, and enjoy the sense of immediacy that creates.

In Speaker of Mandarin, we see Wexford away from the village that provides a closed environment for many of the books in this series. He is in China, where he has completed a police-related mission and joined a British tour group.

In the few days he spends with them, he is haunted by an aged Chinese woman hobbling on her tiny bound feet, seemingly desperate to speak with him. She appears and disappears and turns up at the next stop, the next city, only to vanish again. Is she real, or is Wexford hallucinating? The inspector wonders and worries.

The tour group takes a trip down the Li River, and a man — “Not one of us. A Chinese” — drowns and is forgotten. But months later, back in Kingsmarkham, one of the group is shot in the head, and the plot turns and turns again as Rendell teases the reader into thinking he has the solution — only to surprise him anew.

Other enjoyable titles in this popular series are From Doon with Death (1965), Wolf to the Slaughter (1968), A Guilty Thing Surprised (1970), Shake Hands Forever (1975), and An Unkindness of Ravens (1985).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 15 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller:

RUTH RENDELL – Master of the Moor. Pantheon, US, hardcover, 1982. UK edition: Hutchinson, hc, 1982. Paperback reprint: Ballantine, 1983.

The English moors, with their stark, eerie loneliness, have long fascinated writers of suspense fiction. In this excellent novel of psychological suspense, Rendell utilizes this setting as the scene for a series of murders of women, and the combination of the oppressive atmosphere and the killings takes a horrible emotional toll on those living nearby.

Until he finds the first body, Stephen Walby thinks he knows Vangmoor — considers himself, in fact, “master of the moor.” Daily he traverses its crinkle-crankle paths, up the foins (hills) and past the abandoned soughs (mine shafts).

But on the day he finds the strangled girl’s body, his life changes. The moor, once a popular place, becomes deserted — “known not as somewhere unique and beautiful but as the place where a young girl had been killed.”

Not altogether displeased by this, Stephen begins to visit the moor more frequently. The murders continue, and Stephen often returns from his walks in a feverish state. Occasionally he is as low as his chronically depressed father; and his already stressed marriage begins to fall apart. On top of this, other events begin to make Stephen wonder about his parentage; at times he isn’t sure who he is — or what.

This is one of Rendell’s best novels, and even if the reader begins to suspect what is going on, he can never be sure, up to the last terrifying revelation.

Other equally gripping tales are One Across, Two Down (1971), The Face of Trespass (1974), and A Demon in My View (1976).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

« Previous Page — Next Page »