September 2009

Monthly Archive

Mon 7 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

Reviewed by MIKE GROST:

RUFUS KING – Holiday Homicide. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1940. Paperback reprint: Dell #22, mapback edition, 1943.

Preceded by Murder Masks Miami (1939) the last Lt. Valcour novel, Rufus King’s Holiday Homicide introduces two new sleuths, high priced private detective Cotton Moon, and his secretary-assistant-narrator, Bert Stanley.

The two are direct clones of Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, and the novel as a whole is a pastiche of Rex Stout. Moon is a pleasant character; instead of raising orchids, like Wolfe, he collects rare nuts. The novel might be best read with a copy of Edwin A. Menninger’s Edible Nuts of the World (1977) on hand: a fun book, by the way. This zany hobby is typical of the book’s tongue in cheek approach: nothing is ever completely serious here.

King’s pastiche of Archie Godwin is especially good. King has caught Archie’s bemused, intelligent, slightly smart-alecky tone of narration very closely.

King has combined this tone with his own vivid writing style, to make a very interesting synthesis. The descriptions include King’s interest in rich concoctions, such as food, perfumes, and fluids.

King also uses his typical examination of conventional story telling ideas here, constantly turning over stock phrases and situations, commenting on them all the while — this is an early use of a technique that will reach its apogee in King’s short story “The Faces of Danger” (1960).

Since Archie is also a somewhat sardonic observer of the human scene, King can fuse his own meta-narrative approach with Archie’s “common man” take on the well to do world about him. Bert is a bit more bitchy than Archie usually is, in keeping with the campier tone of King’s fiction.

While Holiday Homicide is well written, it has problems as a puzzle plot. There is no fair play: Moon identifies the killer because he discovers the killer’s fingerprints at a crime scene.

This clue is not shared with the reader, and there is no logical way for the reader to deduce who the killer is. Nor is the mystery’s solution especially clever. It does succeed in making a logical story out of the book’s scramble of events and clues, and this shows a bit of ingenuity.

Holiday Homicide has a similar status as Murder by Latitude in King’s career. Both books are 1) genuine whodunits, not suspense novels; 2) lack fair play in their solutions; 3) are well written, with special gifts of prose style and verbal adroitness; 4) show good storytelling.

Sun 6 Sep 2009

WALTZ OF THE TOREADORS. Independent Artists, 1962. Peter Sellers, Dany Robin, Margaret Leighton, John Fraser, Cyril Cusack. Based on the play The Waltz of the Toreadors by Jean Anouilh. Director: John Guillermin.

I don’t know if I’m alone in the US in this regard or not, but looking back through the IMDB credits for Peter Sellers, the first movie that he was in that I remember seeing was The Pink Panther, which came out in 1963. (I’ve never seen Lolita, which was also a 1962 release, so it looks as though I’m wrong. It’s a certainty that there were a few people who came in ahead of me.)

Then came Dr. Strangelove (1964), which I loved with a passion and could not figure out why none of my college housemates agreed with me. Sellers had been around a while before Waltz of the Toreadors, of course, but I seldom watched British films back then, mostly because I needed subtitles to understand them.

And yes, of course I’m exaggerating, but you know what I mean. They recently had an all-day extravaganza of Peter Sellers movies on Turner Classic Movies, and I taped most of them, telling myself that I couldn’t go wrong. Since I don’t lie to myself — well, hardly ever — I was right.

In Waltz of the Toreadors he plays a retired British officer around the end of the 19th century who has a problem. His wife being a nagging invalid, he has nothing to look forward to in that regard, but even worse, the true love of his life (the beautiful Dany Robin), with whom he has had an unconsummated love affair for 17 years, is coming from France, where he first met her, to take, she believes, her rightful place in his life.

The first half of this movie is then a comedy, with much mugging and horseplay and missed connections, male-female wise, or maybe that should be the first two-thirds. But quietly, it seems, and without much fanfare, the tone of the tale becomes more and more serious, and anyone who expected a happy (or happier) Hollywood ending in which all sides reconcile and make up and find true love — I think they’re going to be disappointed. Unmet expectations, and all that.

Given that the ending is at least somewhat more serious than the rest of the movie, then I think that there at least two problems. Why on earth, one might ask, does Ghislaine (Dany Robin) waste 17 years of her life pining for this general who is hardly worth crossing the street for, one realizes in retrospect, that retrospect being confirmed by the second problem, that General Leo Fitzjohn (that’s Sellers) has no intention of changing his view of the world (and his place in it, including his incredibly womanizing ways), will not change and does not change? Not a budge, not an inch, even when given a truckload of opportunities to do so.

English 101. How did this person’s character change during the course of this book? (Answer. Not at all. He’s as solid as brick.) I hated English 101, so maybe (an understatement) I’m still exaggerating.

On the other hand — and of course, there always is one — that’s the point, I believe, right there in the nut of the shell. What could be sadder than someone who doesn’t change? Or maybe the key word here is “can’t.”

Sun 6 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

Reviewed by MIKE GROST:

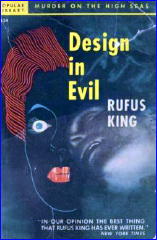

RUFUS KING – Design in Evil. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1942. Reprint paperbacks: Thriller Novel Classic #21, 1943; Popular Library #124, paperback, 1948.

Design in Evil is the first of King’s non-series thrillers, after he abandoned the formal detective novel with Holiday Homicide (1940).

The early chapters (1-13) are well written, with King showing in detail the trap that confronts his heroine. These chapters show King’s feel for sailing material, taking place on a sea going yacht.

Unfortunately, the book as a whole is flat. Design in Evil is in the tradition of the “innocent young woman forced into a new identity” school. It follows such pioneering works as Helen McCloy’s The Dance of Death (1938), and Anthony Gilbert’s The Woman in Red (1941), the latter being made into a superb film directed by Joseph H. Lewis, My Name is Julia Ross (1945).

The story is never plausible, unless everyone is in on this bizarre plot; yet King wants only one person to be guilty, and everyone else to be an innocent dupe. The later sections of the book contain a murder mystery. However, there are only two serious suspects, and the mystery is never developed into an interesting or even very elaborate plot.

King indicates that Joseph Conrad is one of his hero’s favorite authors (Chapter 15). It certainly makes sense that King admires Conrad: both were sailors in real life, and wrote frequently about the sea, and both men wrote rich descriptive prose.

King is of two minds about psychiatry, then becoming unfortunately fashionable in the media. Psychiatry is treated as a serious science, and yet the older psychiatrist is the book is shown as a completely mistaken dupe. This is at least more skeptical than the religious reverence with which psychiatry was usually held in this era.

Editorial Comment: You should go back, of course, and compare and contrast Mike’s review of this book with that of Bill Deeck’s, which I posted here earlier this morning.

If you follow the link in the paragraph above, you’ll find a long section of Mike’s website devoted to reviews and analysis of Rufus King’s work. At the risk of overdoing a good thing, I’m planning on posting one or two more of those reviews on this blog. Look for them tomorrow, if all goes well.

Sun 6 Sep 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

HELLO, FRISCO, HELLO. 20th Century Fox, 1943, Alice Faye, John Payne, Jack Oakie, Lynn Bari, Laird Cregar, June Havoc, Ward Bond. Dances staged by Val Raset and Hermes Pan; musical sequences supervised by Fanchon. “You’ll Never Know,” music and lyrics by Mack Gordon & Harry Warren. Director: H. Bruce Humberstone. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

“You’ll Never Know” won the Oscar for best song and the movie was Fox’s biggest hit of 1943. John Payne is Johnny Cornell, hot-shot small-time musical promoter, whose greatest asset is his long-suffering girlfriend and talented performer Trudy Evans (Alice Faye), with Dan Daley (Jack Oakie) and Beulah Clancy (June Havoc) filling out the quartet of long-time friends and fellow vaudevillians whose stories are the core of this sumptuous, plushy musical.

Lynn Bari is the society dame who can offer Johnny everything he’s always wanted, wealth and position, everything but love, and without giving away any more of the plot, I’m sure you can tell how the film will end.

I always liked Alice Faye, but I was never a great fan of the Fox musicals, which failed to satisfy me in the way the Astaire-Rogers and MGM musicals did.

The movie made me wish that I had not missed the screening earlier that day of Nice Girl? (Universal, 1941), with a cast that included Deanna Durbin, Franchot Tone, Walter Brennan, Robert Stack, Robert Benchley, and Helen Broderick, a comedy with music that, by all the accounts I heard of it, had the charm and light touch that Hello, Frisco, Hello, for all its top-flight production values and talented cast, showed no trace of.

And if you say that I’m comparing apples and oranges, you’re probably right. Let’s just say that I prefer the pungent taste of apples to the pulpy texture of oranges.

Sun 6 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini & George Kelley:

RUFUS KING – Malice in Wonderland. Doubleday Crime Club, 1958. Queen’s Quorum 117.

Rufus King had two distinct “careers” in crime fiction. The first was as a writer of traditional Golden Age whodunits, beginning in 1927 and continuing until 1951. He produced twenty-two novels during this period, most of which are entertaining despite some stilted prose; they are marked by clever plotting, interesting backgrounds, and touches of gentle humor.

King’s best work, however, is his short fiction, particularly that written during his second “career” in the 1950s and 1960s when he abandoned novels altogether and concentrated on stories for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

Malice in Wonderland, the second of King’s four collections, was so highly regarded by the Mssrs. Queen that they included it in their Supplement Number One (1951-59) to the Queen’s Quorum.

The eight stories here expose the violence and corruption of the fictional town of Halcyon, Florida — after the fashion, if not in the style, of John D. MacDonald. Queen said that in these stories King “pungently, almost maliciously impale[s] … the Gold Coast, that fabulous neon strip between Miami Beach and Fort Lauderdale, with its cross section of natives and tourists, of greedy heirs and retired gangsters (alive and dead).”

The best story in the collection, “The Body in the Pool,” traces the strange connection between the state of Florida’s electrocution of murderer Saul (“Stripe-Pants”) McSager and the selection of Mrs. Warburton Waverly as the county’s “Most Civic-Minded Woman of the Year.”

Also excellent are the title story, in which a girl tries to decode a message from a long-dead playmate; and the long novelette “Let Her Kill Herself,” in which an unpleasant woman makes an extremely disturbing discovery.

Some of King’s early short stories are collected in Diagnosis: Murder (1941). Two other collections of stories about Halcyon and the Florida Gold Coast, both of which rank with Malice in Wonderland, are The Steps to Murder (1960) and The Faces of Danger (1964).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 6 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by George Kelley:

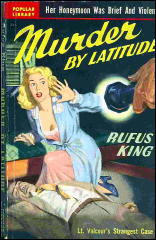

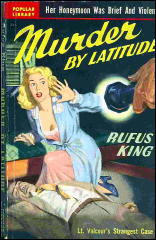

RUFUS KING – Murder by Latitude. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1930. Reprint paperback: Popular Library #246, 1950. (Cover art: Rudolph Belarski.)

Rufus King’s sole series character was a New York police detective, Lieutenant Valcour. A proper gentleman detective, Valcour’ s only unusual characteristic is that he is a French Canadian.

Murder by Latitude is one of Valcour’ s more exotic cases. The Eastern Bay is a cheap passenger-carrying freighter making a Bermuda-to-Halifax run. Lieutenant Valcour boards the ship with the news that one of the passengers is a murderer.

One of the victims is dead of strangulation, the other is in a New York City hospital; police are hoping this victim will recover to give a description of the killer. The murderer sabotages radio communication so police can not send the description of the guilty party, but Valcour has clues that indicate the murderer is aboard the Eastern Bay and he starts his investigation on his own among the bizarre menage of passengers.

As the degrees of latitude sail by, the murderer strikes again, leaving such cryptic clues as a lump of wax, a stolen thimble, and a pair of scissors. Valcour achieves some impressive feats of detection to tie the clues to the culprit in classic fashion.

Another recommended Valcour sea mystery is the fine Murder on the Yacht (1932). Valcour made an impressive debut with Murder by the Clock (1929) and went on to detective fame in a half-dozen novels, concluding with Murder Masks Miami (1939).

Notable among King’s nonseries novels are A Variety of Weapons (1943), The Case of the Dowager’s Etchings (1944), and Museum Piece No. 13 (1946).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 6 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

RUFUS KING – Design in Evil. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1942. Reprint paperbacks: Thriller Novel Classic #21, 1943; Popular Library #124, paperback, 1948.

Dr. Crowninshield, an authority in the psychiatric area who has reached an age and a level of experience that allows him to abandon doubt and uncertainty, has concluded, after no examination whatsoever, that Miriam Lake is really Jennifer Murcheson, wealthy and very peculiar even when normal, who mysteriously left her ranch In California and is now suffering from schizophrenia.

Crowninshield’s assistant, Dr. Stone, is also convinced that Lake is Murcheson, but he is certain she is faking the alleged illness.

By some dastardly plotting and a little arson, the Murcheson family — uncle, aunt, and cousin — get Lake aboard their yacht en route to the Caribbean. Ostensibly the purpose is to effect a cure. Lake, however, begins to realize that it is someone’s design to murder her at sea in order to gain the real Murcheson’s fortune.

With the “scientists” aboard the vessel having their minds made up, her claims and attempts at proof are ignored. Thus her situation is both frustrating and perilous.

The more I read of Rufus King’s novels, the more I am impressed by their general high level. His plotting is usually first class, the atmosphere of menace is almost always well done, his suspects are often few, something appreciated by this feeble-minded reader, and the clues are generally fair.

While he has a weakness for polysyllables, so do I. Characterization sometimes is a bit weak, but King often makes up for it by his humor. In this novel, Lake’s amusing comments in the face of her obvious danger keep the novel from becoming just another damsel-in-distress type.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988

(slightly revised).

Sat 5 Sep 2009

I’ve recently annotated another grouping of authors’ entries from Part 34 of the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

If the author in entry one below seems out of place at first, you’ll see why it’s here soon enough, I believe. One significant update is the disambiguation of two authors with very similar sounding names, Harlan Eugene Read and Harlan (M.) Reed.

BROTHER JAMES. Pseudonym of [Dr.] James Reynolds, – 1866, q.v.

-The Adventures of Moses Finegan, an Irish Pervert. Duffy (Dublin), 1885. Previously published as by James Reynolds: Duffy (Dublin), 1870.

READ, CHARLES A(NDERTON). 1841-1878. Add as a new author. Born in Ireland; merchant in Rathfriland, County Down; went to London in 1863, where he became a journalist. During his writing career the author of numerous sketches, poems, short tales and nine novels, two of which are criminous in nature:

Aileen Aroon; or, The Pride of Conmore. Henderson (London), 1870. Setting: Ireland. First appeared in The Weekly Budget. “Garratt O’Neill is falsely accused of murder.”

Savourneen Dheeush; or, One True Heart. Henderson (London), 1869. Setting: Ireland. First appeared in The Weekly Budget. [Based on the Wildgoose Lodge Murders of 1816.]

READ, HARLAN EUGENE. 1880-1963. Add biographical information: Born in Jacksonville IL; educated at Oxford University and Brown’s Business College; editor; did syndicated newspaper work; St. Louis radio news commentator. Author of one book in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. See below:

-Thurman Lucas. Macmillan, US, hc, 1929. Add setting: St. Louis, East St. Louis IL, and Nevada; early 1900s. [After several scrapes with the law in the Midwest, a man becomes a success in the mining fields of Nevada.]

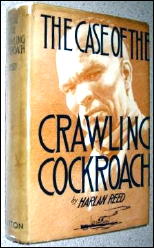

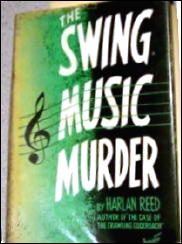

REED, HARLAN (M.) 1913-2001. Add middle initial, years of birth & death, and the following biographical information, replacing the previously incorrect data: Born in Nome, Alaska, raised in Seattle. graduate of University of Washington, where he also taught creative writing. Ran family oil business in Vancouver WA after WWII; photographer and jazz pianist. Author of two mystery novels in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. Below is the author’s complete entry. Series character in each: hard-drinking “idiosyncratic” private eye Dan Jordan.

The Case of the Crawling Cockroach. Dutton, hc, 1937. Setting: Ship.

The Swing Music Murder. Dutton, hc, 1938. Setting: Seattle WA.

REID, LIZZIE C. Add as a new author. Short story writer who lived in Belfast, Ireland; her stories appeared in The People’s Friend and other periodicals.

-The Doctor’s Locum Tenens. Sealy (Dublin), 1907. Setting: Ireland. “A lady doctor’s adventures in an Ulster town. […] Interwoven with a narrative of mystery and plotting there is a pleasant love story.”

REYNOLDS, [DR.] JAMES. -1866. Add as a new author. Pseudonym: Brother James, q.v. Lived in Booterstown, County Dublin. Short story writer; contributed several serials to Duffy’s Fireside Magazine under the additional pen names E. L. Berwick and “A Well-Known Novelist.”

-The Adventures of Moses Finegan, an Irish Pervert. Duffy (Dublin), 1870. Also published as by Brother James: Duffy (Dublin), 1885. Setting: Ireland. [The protagonist, although married, goes with a benefactor’s daughter to America, where he is later sentenced to death for her murder.] Note that the word “pervert” in the title is used here in the religious sense, as the opposite of “convert.”

Sat 5 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

LEO PERUTZ – Master of the Day of Judgment. First US edition: Boni & Liveright, hardcover, 1930. Translation of Der Meister des Jüngsten Tages (Munich, 1923). Reprint editions include: Charles Boni Paper Books [#7], 1930; Collier AS 528V, pb, 1963; Arcade Publishing, hc, 1994.

Thus the whole sinister and troubled business lasted five days only, from 26-30 September. The dramatic hunt for the culprit, the pursuit of the invisible enemy who was not flesh and blood, but a fantastic ghost from past centuries lasted only five days. We found a trail of blood and followed it. A gateway to the past quietly opened … step by step down a long dark passage at the end of which a monster was waiting for us with upraised cudgel.

So opens Austrian fantasist Leo Perutz’s 1924 novel, a gothic thriller, locked room detective novel, fantasy, and example of the novel as jest of a kind we are familiar with today in the wake of Nabokov, Joyce, Pynchon, and others, but which must have come as a revelation in Austria in the period after the devastation of WW I as the Austro-Hungarian Empire reeled on it’s last desperate legs.

To begin with, Eugen Bischoff, the actor, is dead, found in a locked room, the only clue a pipe belonging to the tales narrator Baron Von Yosch, a distinguished soldier and adventurer, and lover of the actor’s wife Dina.

Dina’s brother sets out to convict Von Yosch, while his friends set out to clear him, and soon things get complicated, as a series of suicides strike across the city, each coming nearer to Von Yosch, and seemingly aimed at him.

As Dr. Gorski, the Sherlock Holmes figure points out: “Don’t you see the diabolical trap? The seat of the imagination is also the seat of fear.”

“Fear and imagination are inseparably linked. The great phantacists (sic) have always been obsessed by fear and terror. Think of E.T.A. Hoffman, Michelangelo, Breugel, Edgar Allan Poe.”

And it is to Poe, Hoffman, and later writers such as Borges this book with its affectionate turn on popular fiction owes much of its charm and power.

Admittedly this is hardly a fair play mystery, and Barzun and Taylor are hard on it in Catalogue of Crime simply by their having imagined it was ever meant to be taken as one. Indeed the solution (or at least the first solution) involves one of those drugs unknown to science right out of Sax Rohmer and the doings of Dr. Fu Manchu; the Detection Club would be horrified:

“It’s very ancient, and it’s origin is no doubt sought in the East. Fire and ecstasy. Have you ever taken an interest in the Assassins? Today you may have held in your hands the drug, or one of the drugs, by which the Old Man of the Mountain controlled men’s minds.”

And then Perutz turns all that has gone before on its head in a moment worthy of Agatha Christie, the novel becoming a psychological mystery:

Was it a revolt against inalterable fate? But looked at from a higher stand point — has this not always been the origin of all art? Does not every eternal masterpiece derive from the experience of disgrace, humiliation, wounded pride? … the great vision that for a moment raises the master above his tormenting guilt.

Perutz was a master of the literary twist, the kind of gamesmanship we have grown accustomed to today, but seldom accomplished with his economy and skill as an artist.

Among his best known books are Leonardo’s Judas, The Marquis of Bolibar, Saint Peter’s Snow, and By Night Under the Stone Bridge. These are works that belong beside Borges and Nabokov, and like them often play with the familiar tropes of popular literature, the adventure story, detective story, mystery, and the true gothic romance.

Acclaimed by Graham Greene, Ian Fleming, Jorge Luis Borges, and Italo Calvino, Perutz is a fantasist, but his fantasy arises from realism and his works often have the qualities of 1001 Arabian Nights or The Saragosa Manuscript, stories within stories, hidden meanings. signs, and mysteries deeper than merely who-dun-it.

Truth and even beauty found among the musty trappings of the gothic imagination and the familiar forms of the detective novel.

Reading Perutz may alter your perception of popular fiction. For a while you may find yourself expecting twists that never come and outcomes most authors never intended, but it is worth the trouble.

As does Borges, he finds deeper mysteries lurking in the shadows of genre fiction and like Nabokov illuminates them with a quiet but barbed humor. That his eye is also sharp as a scalpel and cuts as deeply is only one of the bonuses of discovering his work.

Fri 4 Sep 2009

THE DIVORCE OF LADY X. United Artists (UK/US), 1938. Merle Oberon, Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Binnie Barnes, Morton Selten. Director: Tim Whelan.

The print of this film I recently watched on TCM must be a new one, or that is to say, one that’s been remastered, cleaned up and refreshed, since the colors in this early Technicolor comedy romance are vivid and bright — they’re really quite spectacular if not dazzling — while many of the comments that have been left on IMDB are complaints about the poor quality of the color, pale and not only faded, but fading in and out.

They all seemed to like the movie itself, however, and so did I, up to a point, and I’ll get back to that in a paragraph or so. It all begins in a London pea soup of a fog, and the crowd who’ve been attending a masquerade ball at a hotel are forced to stay there all night — without rooms for everyone, amusingly enough.

The amusement grows even more so when a young minx of a lady (not a contradiction) inveigles her way into the suite that a barrister named Everard Logan (Laurence Olivier) had claimed for himself earlier in the evening and is unwilling to share it with any of the others who have found themselves fogged in.

Not only that, but Leslie Steele (that’s her name), played by Merle Oberon, as you must have guessed, takes over Logan’s bed as well. Since this movie was made in 1938, you needn’t even begin to worry that something untoward happens. Logan sleeps on a mattress on the floor outside the bedroom in the suite, and one can easily imagine that the door between was locked.

Any other imagining would be left to the viewer, but those would be thoughts of what might have been only — you can take it from me: there is no hanky-panky that goes on in this film.

The cinema was different in 1938 than it is today, and it is all very amusing how cleverly Leslie Steele outwits her slow-witted male counterpart in this movie to take over his bed so neatly and slyly (and so innocently) as this.

The second half of the movie, while still amusing, is an anti-climax from here on, at least in comparison. Logan, as it so happens, is a divorce attorney … Wait, wait. I forgot to tell you this. In the morning, Logan discovers that he has fallen in love with the mischievous young lady who took over his accommodations, but she skips out without even telling him her name.

To get back to the divorce proceedings, Logan’s very next client is a gentleman (Ralph Richardson) who wants a divorce from his wife because — you’re ready for this, aren’t you? — she stayed overnight in that same hotel the exact night before in the rooms of another man.

Logan, of course, jumps to the immediate conclusion that the other man is none other than himself.

A merry mixup up like this in Part Two could have as amusing as the clever shenanigans in Part One, but dragging the charade out for far too long, as it’s done here, eventually begins to feel cruel and mean-spirited.

This is only one person’s point of view, you understand — mine, that is — and I seem to be in the minority on this, so by all means, if you’d like to see two great stars in fine action, romantic comedy style, even if it turns into a frothy mess — relatively speaking — then by all means, put this one on your list of movies to see as soon as you can.

Be sure to watch the restored print, though. It really is an eye-catcher.

And do you know what? I’m even willing to bet that I’ll like the entire movie more myself, the next time I watch it!

« Previous Page — Next Page »