February 2010

Monthly Archive

Tue 16 Feb 2010

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

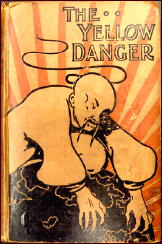

M. P. SHIEL – The Yellow Danger. Grant Richards, UK, hardcover, 1898. R. F. Fenno, US, hc, 1899. Reprinted many times.

Matthew Philips Shiel has to be one of the most eccentric writers of all time. Racist (despite the fact he was of mixed race himself), jingoist, and mystic, he is probably best known today for his Last Man on Earth novel The Purple Cloud and his stories about decadent sleuth, the neurasthenic Prince Zaleski, but for pulp fans he holds a special place — as the inventor of the “Yellow Peril” novel.

Before Shiel the “Italian Peril’ had been the biggest trend in popular fiction. Guy Boothby’s Dr. Nikola had a long successful career plaguing a series of English heroes (Nikola deserves to be rediscovered, and all the books are available to read free on-line as well as others by the popular and talented Australian Boothby), and Italian villains with ties to ‘the Black Hand’ and other such secret societies had shown up in the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Nick Carter, Sexton Blake, and books such as L. T. Meade’s and Robert Eustace’s The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings (also available free on-line and worth checking out, a clever and entertaining thriller from an earlier age).

The Yellow Danger is a novel in the sub-genre of stories known as invasion or future war novels that began with The Battle of Dorking and reached its highpoint with H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds. William LeQueux made a near cottage industry of these, and classics of the form include Erskine Childer’s prophetic Riddle of the Sands and Conan Doyle’s Danger! (which predicted submarine warfare in WW I).

Modern examples include Vandenburg by Oliver Lange, I, Martha Adams by Pauline Glen Winslow, SGB by Len Deighton, and films such as Red Dawn and Invasion USA.

I won’t go into the historical reasons for the rise of the “yellow peril” novel here. Suffice it to say that as much as anything the Boxer Rebellion, in which a fanatic secret society with backing from the Chinese government led to the siege of the embassies in Bejing (see Peter Fleming’s The Siege of Peking and the film 55 Days in Peking), and the subsequent military action by allied forces of the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and Japan among others, and the growing population of Chinese in Western cities and the sensationalist reporting of the era on the activities of the criminal “tongs” and the “yellow peril” only needed the right book to set the whole thing off.

The Yellow Danger was that book.

The novel opens as England faces a crisis in the East at the hands of the Germans, Russians, and French (Shiel was an equal opportunity jingoist), but it is at a simple garden party for a charity that we first meet the source of “the yellow danger” —

“Just allow me to introduce my friend here — Miss Seward — Dr. Yen How.”

In the light of the ’bus lamp Ada Seward saw a very small man dressed in European clothes, yet a man whom she at once took to be Chinese. With a wrinkled grin he put out his hand and shook hers.

He was a man of remarkable visage. When his hat was off, one saw that he was nearly bald and that his expanse of brow was majestic. There was something brooding, meditative in the meaning of his long eyes; there was a brown, and dark, and specially dirty shade of yellow tan to his skin.

He was not really a Chinaman, or rather he was that, and more. He was the son of a Japanese father by a Chinese woman. He combined these antagonistic races in one man. In Dr. Yen How was the East.

That “expansive majestic brow ” must surely remind readers of Sax Rohmer’s Dr. Fu Manchu and his “brow like Shakespeare.” And Shiel makes no bones about the doctor’s motives for his evil machinations —

Yen How was nothing if not heathen. He was that first of all.

His intellect was like dry ice. Though often secretly engaged in making The Guess, on the whole he despised all religions — faiths of the West, the superstitions of the East, he despised them all alike. He was full of light, but without a hint of warmth; and so lacked religious emotion.

It is not likely that ordinary ethical considerations would much influence the aims of such a man. He was like an avalanche, as cold and as resistless.

What was Dr. Yen How’s aim? Simply told, it was to possess one white woman, ultimately, and after all. He had also the subsidiary aim of doing an ill turn to all the other white women, and men, in the world.

To say the least the horse was out of the barn and bolting. You can’t accuse Shiel of beating around the bush. He jumps in with both feet. It’s not long before the evil Dr. Yen How has the world crumbling and the West trembling as the hordes of the East (ever since Genghis Khan Asian armies always seem to move in hordes).

Luckily for us England has men like Shiel’s Nietzschean hero John Hardy to call on —

There could be no doubt that John Hardy’s long-lashed, azure blue eyes possessed the faculty of

seeing.

As the crisis rises and the Asian hordes sweep across the west the consumptive but heroic Hardy rises in short time from unknown officer to Admiral of the fleet.

Under the English banner the treacherous Russians, Germans, French and others rally, and Kaiser Bill himself leads an army under the Union Jack in a great land battle, but it is Hardy who must destroy Dr. Yen How and his hordes, and his choice of weapon is perhaps the most far seeing and startling of Shiel’s predictions.

Hardy uses the young woman, Ada Seward, who Dr. Yen How desires, to get to the leader of the Asian invaders and infects the Dr. and the invading armies with plague — a bit of payback since the invading Mongols introduced the disease to Europe in the first place back in the days of Genghis Khan.

To be fair, mass murder weighs heavily on Hardy in a chapter entitled “Hardy’s ‘Crime'” —

He was no longer sane. His hand was thicker that itself with his brother’s blood. His final hour of darkness was hastening to meet his life. All his sky was an ink of clouds. Now again, he tarried, cowering, in Gethsemane.

The Asian armies die by the millions, Dr. Yen How succumbs to his ‘unnatural desire’ for a white woman, and the triumphant Hardy, the beloved leader of the white race, dies of the consumption eating away at him, leaving the world in the safe hands of the Pax Britannica, all of Europe now under the firm hand of the Union Jack from the English Channel to the Russian Steppes.

The Yellow Danger is relatively hard to find but you can download a facsimile in pdf format or read it on-line.

It’s a remarkable book, not just for its distasteful jingoism and racism, but also because so many of the cliches and stereotypes of the sub genre are already present: the stalwart English hero; the inhumanly cold intelligence and yet base passions of the Asian villain; the fear of racial impurity; the swarming hordes of sub-human and alien forces; and the fear of the unknown.

Nor is The Yellow Danger Shiel’s only contribution to the invasion novel and the paranoid fear of the foreign. Lord of the Sea is the story of an English Jew who conquers the seven seas and is ultimately destroyed by his desire for a pure English woman. Luckily the “Jewish Peril” didn’t quite catch on despite the nonsensical and wholly fictitious Protocols of Zion and rampant Anti-Semitism.

No doubt about it, this can be unpleasant stuff, but it also has historical import both socially and to the genre as a whole.

It was Shiel who moved the world’s eyes East and spawned a long line of “Yellow Perils,” a genre that still lingers long past the heyday of the Fu Manchu’s, Dr. Wu Fang’s, the Shadow’s Shiwan Khan, and Dr. No’s of yesteryear. The list of Asian super villains is impressive and still growing.

The genre is far from dead even today (although the “yellow peril” currently has been replaced by the “Islamic peril”). Clive Cussler has written at least two novels that fall in this category (Dragon and Flood Tide) and is hardly alone. One hundred and twelve years later popular fiction is still haunted by the “yellow peril” stereotype.

A new Fu Manchu novel appeared in 2009 (The Terror of Fu Manchu from Black Coat Press). There’s even a distaff “yellow peril” with Sax Rohmer’s Sumuru and Andre Caroff’s Madame Atomos (also being reprinted by Black Coat Press), and books like Alexander Cordell’s The Deadly Eurasian and Richard Condon’s The Whisper of the Axe send up of the whole thing offering a new take on old cliches.

Richard Jacoma’s The Yellow Peril is a good example of having it both ways, a “yellow peril” novel seen through modern eyes, and K. K. Beck’s The Revenge of Kali Ra (reviewed here ) sends the whole thing up as well as taking shots at Hollywood and Sax Rohmer.

But be warned: If you are easily offended or bothered much by what is or is not politically correct, The Yellow Danger may be hard going.

Shiel was a very unpleasant man by all accounts and eccentric as both a writer and a human being. Still, if you are interested in the history of the genre and the origin of many of its stereotypes and cliches this one is hard to ignore.

In its wake march armies of shadowy geniuses hidden in the foggy street of Limehouse or Chinatown and gathering their forces in distant exotic lands.

We may have outgrown some of Shiel’s more obvious prejudices, but it may be a wise thing to compare them to our own modern flaws and ask ourselves if we have really moved that all that far in the one hundred and twelve years since The Yellow Danger first saw print.

There are writers today — Brad Thor and John Ringo come to mind — often found on the bestseller list, whose popular books are, in their own way, no less sensationalist, jingoistic, and intolerant as Shiel’s work.

We are in no position to condemn without first examining our own failings.

Note: The anthologies It’s Raining Corpses in Chinatown and It’s Raining More Corpses in Chinatown edited by Don Hutchinson (Starmont House) offer a good selection of “Yellow Peril” stories from the pulps plus a good history of the genre and bibliography of “Yellow Peril” fiction from writers like Frank Gruber, Steve Fisher, Richard Sale and others for those interested.

COMMENT [02-17-10] From Jess Nevins, author of Fantastic Victoriana —

To be precise and in terms of the facts, Shiel didn’t invent the Yellow Peril novel. I believe that David has grossly overstated Shiel’s development of the trope. It was already commonly used by the time Shiel wrote his book.

I wrote about this, at length, in Fantastic Victoriana, but, briefly:

Numerically, the Italian Yellow Peril peaked with suspense fiction, in the 1870s. Anti-Asian sentiment rose from mid-century, and in both Britain and the US the 1880s were when it surged upwards, and not just in the U.S. It was Albert Robida, in France, who wrote “La Vorace Albion” (1884), with its various Asian villains.

But in the US you’ve got Robert Woltor’s A Short and Truthful History of the Taking of Oregon and California by the Chinese in the Year A.D. 1899 (1882), you’ve got Emma Dawson’s “The Dramatic in My Destiny” (1880), Ellen Sargent’s “Wee Wi Peng” (1882), the various dime novel Yellow Peril villains (far outnumbering Italian villains), culminating in Kiang Ho (1892), enemy of Tom Edison, Jr.

You’ve got Robert Chambers’ Yue Laou, in The Maker of Moons (1896), and you’ve got C.W. Doyle’s Quong Lung (short stories, 1897-1898).

It was an established literary trope and even a cliche by the time Shiel got to it. It predated the Boxer Rebellion in non-fiction and fiction by, oh, about 40 years. Shiel *capitalized* on it, but he didn’t establish it. Yellow Papers were in the British story papers and American dime novels a full decade before Shiel.

RESPONSE [02-17-10] David’s reply:

I am not suggesting Shiel invented the idea of Asian villains in popular fiction. Certainly the influx of Asians on the Western Coast of the United States after the Civil War and the growth of Chinese sections of major cities in the West were major contributing factors in the growth of the field.

This was complicated by the language and cultural barriers and the tendency of the Chinese and Japanese to stay in their own communities (not that they had much opportunity to move out of them if they had wanted to). Just as the Irish, Italians, and Jews all suffered similar demonization at various times as their communities grew in major cities.

But The Yellow Danger is generally attributed by most critics (Don Hutchinson, Robert Sampson, Brian Aldiss, and others) as the book which put the “yellow peril” on the map of popular imagination. Historically Shiel’s book helped to move a vague prejudice from the background of popular culture to one of the most recognized stereotypes of 20th Century popular imagination.

In any case no one can argue that Sax Rohmer and Fu Manchu “invented” the genre and yet no one can argue that the “yellow peril” would still be with us without the good doctor’s influence.

First is not always important in popular fiction. Sherlock Holmes wasn’t the first detective, James Bond wasn’t the first post war secret agent, Fu Manchu wasn’t the first Asian super villain, the Virginian wasn’t the first western, Tarzan not the first feral man, John Carter not the first interplanetary traveler, and Zorro wasn’t the first masked caped hero with a secret identity — none the less their role is important and vital to the sub genres they represent. The Yellow Danger was neither new nor unique, but it was important in establishing a still existing sub-genre.

LATER:

I do regret loosely using “inventor” as if there had been no Asian villains before Shiel, but I do think Jess vastly underrates the importance of the Boxer Rebellion in the rise of the genre in the 20th century, and the importance of Shiel’s book — which is hardly unique to me, as I pointed out earlier.

When I was researching Chinese secret societies and particularly the Boxers for Dr. John Y. Moon (former Foreign Minister of South Korea and head of the History Department of the University of Mexico in Mexico City), he brought the Shiel book to my attention as the “turning point” in the use of the “yellow peril” in fiction (ironically Dr. Moon was a Rohmer and Fu Manchu fan and introduced me to “yellow peril” fiction — though as he laughingly pointed out, Fu Manchu was Chinese, not Korean — and though he never missed a Wo Fat episode of Hawaii Five-O either). I grant his opinions and work influenced my article (and a life time interest in secret societies in general in fact and fiction).

Tue 16 Feb 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Thomas Baird:

DICK FRANCIS – Forfeit. Harper & Row, US, hardcover, 1969. Michael Joseph, UK, hc, 1969. Reprinted many times.

Dick Francis not only uses his racing experience in his novels, but in many of them other facets of his life form the background. In Forfeit, his sixteen years as racing correspondent for the London Sunday Express is embodied in the hero, James Tyrone, journalist.

Tyrone listens to a drunken tirade from an old-time colleague who then goes back to his office and nips out the seventh-floor window onto Fleet Street. With a nose for a good story, Tyrone smells a fiddle and starts some inquiries.

He knows he’s on to a sure thing when he hears of blackmail and is met with unexplained violence. As a reporter, he is at great pains to protect his sources, but the dangerous headlines run by his “dreadful rag” of a paper focus the menace on him.

In typical Francis style, the fast-paced writing brings out the individuality of the hero, even though it’s a typical suspense/thriller situation of a normal human being trapped in an abnormal situation. In another bit of autobiographical content, Tyrone’s wife is confined to a respirator and requires constant attendance (Francis’s wife once had polio).

Unusual for a Francis novel, a true love story is depicted even though Tyrone feels that he lives a shadow life-full of “dust and ashes.” In his pursuit of racketeers who force owners not to start their horses in a race, he faces extortion, blackmail, and “high-powered thuggery” (more violence), along with a splash of racism.

He confronts the villain in the Big Cats’ House in London Zoo, and comes face-to-face with an evil sociopath who’s in it for the money. In the end, Tyrone saves his wife while made drunk by the villains, and then must save himself.

Forfeit won a well-deserved Edgar as Best Novel of 1969. Francis’s recent novels have all been large-scale best sellers. The Danger was one; others are Reflex (1981), Twice Shy (1982), Banker (1983), and Proof (1985).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright ? 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 16 Feb 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Thomas Baird:

DICK FRANCIS – The Danger. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, US, hardcover, 1984. Michael Joseph, UK, hc, 1983. Reprinted a number of times.

For some time after he achieved bestsellerdom in the United States, it seemed that Dick Francis (according to some critics) was not keeping up the pace. But with The Danger, he is back in front, writing prose as crisp and taut and lean as a racehorse. This novel runs in the really big international thriller category, starting with “there was a Godawful cock-up in Bologna.” It’s about kidnapping with a touch of terrorism.

Andrew Douglas works as a partner in the firm of Liberty Market Ltd., whose credo is to “resolve a kidnap in the quietest way possible, with the lowest of profiles and minimum action.” He successfully gets back the kidnap victim, Alessis Cenci, “one of the best girl jockeys in the world.”

They go back to England, where he engages in some psychological rehabilitation. This leads to the next hurdle, another kidnap (literally, a kid this time), and he sees a thread of connection. Douglas has the opportunity to assess his opponent — “Kidnappers are better detectives than detectives, and better spies than spies.”

Then, it’s a leap across the Atlantic, where the senior steward of the English Jockey Club is kidnapped in Washington, D.C. — a snatch related to the first two. Apparently Dick Francis likes the States, because he has his chief character say, “I feel liberated, as always in America, a feeling which I thought had something to do with the country’s own vastness, as if the wide-apartness of everything flooded into the mind.”

Andrew Douglas finally comes face-to-face w,ith his adversary genius in an exciting climax.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 15 Feb 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Thomas Baird:

DICK FRANCIS – Odds Against. Harper & Row, US, hardcover, 1966. Michael Joseph, UK, hc, 1965. Reprinted many times. Adapted as the first segment of The Racing Game, a six-episode TV series starring Mike Gwilym as Sid Halley.

In most of his books, Dick Francis uses an ordinary man (usually connected with the racing world) as his protagonist, caught up in events that are so overwhelming and out of control that he must make heroic efforts to sort them out.

But in Odds Against, Sid Halley has a job as a detective-the obvious choice for a tough man to right the world’s wrongs. He’s been doing the work for two years, and when he’s shot (on page one of the story), he realizes that a bullet in the guts is his first step to liberation from being of “no use to anyone, least of all himself.”

He was a champion steeplechase jockey, that’s what makes him tough. A racing accident lost him the use of his hand and self-respect simultaneously.

The action breaks from the starting gate and blasts over the hurdles of intrigue, menace, and crime. Halley is cadged by his shrewd and loving father-in-law into confronting Howard Kraye, “a full-blown, powerful, dangerous, bigtime crook.”

On the track he encounters murder, mayhem, plastic bombs, and torture. But he endures, in some part to regain his self respect, and in some part because he believes in racing, the sport, and in putting it right.

A fascinating chase through an empty racecourse defies the villain. In the end, despite his tragedy, Sid Halley sees himself as a detective and as a man.

Dick Francis was so taken with the characters in this book that he went on to use them in a television series, The Racing Game (shown on Public Broadcasting). A second Sid Halley novel, Whip Hand, won the British Gold Dagger Award in 1979 and another Edgar from the Mystery Writers of America.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 15 Feb 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Thomas Baird:

DICK FRANCIS – Blood Sport. Harper & Row, hardcover, 1968. Michael Joseph, UK, hc, 1967. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft.

From the winning world of British steeplechasing (where he was Champion Jockey in 1954), Dick Francis moved effortlessly into crime fiction with his first novel, Dead Cert, in 1962, and continues to be a front-runner.

He has written twenty-some excellent thrillers full of old-fashioned moral polarity with strains of humor. These “adventure stories” (as Francis calls them) have amazing plots of clever evilness and feature nonrecurring heroes familiar with the racing game.

Flawed, uninvolved, and soulless, each central character finds the value of vulnerability and returns to the land of the living through courage and love. As a central theme, it can be compared to that of the works of Ross Macdonald. As critic John Leonard said, “Not to read Dick Francis because you don’t like horses is like not reading Dostoevski because you don’t like God.”

In Blood Sport, death lurks on a simple Sunday sail on the Thames. An American visitor is almost drowned, and his rescuer is convinced that it wasn’t simply an accident.

Gene Hawkins, the rescuer and hero, is an English civil servant, a “screener” who checks employees in secret-sensitive government jobs. His training permits him to spot details that make “accidents” phony, and his knowledge of guns and listening devices comes in handy. The rescued man asks for help in locating a stolen horse that has just been bought for a huge price.

Hawkins is relieved to use his vacation time to hunt for missing horses, because he is despondent, filled with a “fat black slug of depression.” This is the only part of his character that doesn’t ring true-after all, it’s only a failed love affair.

The pace picks up, and the scene changes to the U.S.A. From the farms of Kentucky, the trail is followed to Jackson, Wyoming. Along the way, Hawkins gets people together for some psychological reconditioning and exposes a bloodline scam as the scene shifts to Santa Barbara, Las Vegas, and Kingman, Arizona.

The U.S. tour is fast-moving, and Francis does not dwell on local-color background, especially not to make any points. He just gives the graphic, journalistic details of a place that push the story along

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

DICK FRANCIS, R. I. P. (1920-2010). Another giant has left us. Dick Francis died on Sunday at the age of 89. A long obituary appears online here at the Daily Mail website, but it is just one of many, not including dozens and dozens of tributes to be found on mystery-oriented blogs.

Francis was the author of 42 thriller novels, all of them having horse racing as a major part of the story. In 2000 Queen Elizabeth II honored Francis by making him a Commander of the British Empire. During his long career he won three Edgar Allen Poe awards given by the Mystery Writers of America for his novels Forfeit (1968), Whip Hand (1979) and Come to Grief (1995).

He also was awarded a Cartier Diamond Dagger from the Crime Writers’ Association for his contributions to the field, and they made him a Grand Master in 1996 for a lifetime’s achievement.

After a lengthy hiatus following the death of his wife, Francis recently began writing again, working with his son Felix to produce Dead Heat (2007), Silks (2008) and Even Money (2009). A new novel entitled Crossfire will be published this year.

Editorial Comment: As I continue this tribute to Dick Francis, over the next couple of days I will be posting several more reviews of his work, all also by Thomas Baird and taken from 1001 Midnights. Their titles: Odds Against, The Danger, and Forfeit.

Mon 15 Feb 2010

EAST SIDE, WEST SIDE. MGM, 1949. Barbara Stanwyck, James Mason, Van Heflin, Ava Gardner, Cyd Charisse, Nancy Davis, Gale Sondergaard, William Conrad, Douglas Kennedy, Beverly Michaels, William Frawley. Screenplay: Isobel Lennart, based on the novel by Marcia Davenport. Director: Mervyn LeRoy.

The book this movie is based on is not included in Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, nor without having a copy in my hands, but relying on what I have read about it on the Internet, do I believe it should be. It’s described by one source as a novel about the “post-war social strata in New York [City]” and that those who love the social history of the city should enjoy it immensely.

Hence the title, of course, and never the twain shall meet — except of course for the fact that they do, and when they do, the results can be both devastating and disastrous to everyone involved. And buried in the otherwise soapy melodrama that constitutes the bulk of the movie based on the book, right around the three-quarters mark, is 15 minutes of crime drama that made me sit up and take notice.

Truth in reviewing: I’d avoided reading about the movie and the storyline beforehand, but when I saw William Conrad’s name in the credits, that gave me some advance notice, and of course Barbara Stanwyck is no stranger to noir-oriented movies, is she?

Consider, then, the following set of interlocking triangles. I’ll omit the characters’ names, and refer to them only by the actors. Stanwyck is married to vain and self-centered Mason, who is infatuated with the beautiful Gardner, who knows it and who hangs out with nightclub owner Kennedy, whose other girl friend is brassy blonde Michaels.

Returning from Europe as a WWII correspondent is Heflin, a non-society guy who falls in love with Stanwyck; he in return is the object of a schoolgirl crush, that of Charisse, who is a fashion model whom Stanwyck knows from the shows she attends, and who (Charisse) saves Mason from an embarrassing newspaper scandal by rescuing him after he’s punched out by Douglas (remember him?)

Eventually a murder occurs, and this is where Conrad comes in — a homicide detective. Frawley is a bartender in Douglas’s night club, just to make sure I’ve mentioned everybody. Well, almost: Davis is one of Stanwyck’s society friends and a close confidant, and Sondergaard is her mother, whom Mason thinks he has utterly charmed.

There is one scene in this movie that I will not forget, one in which Barbara Michael (described as being built like the Empire State Building) and Van Heflin have a brief but ferocious bare-knuckle fist fight. (In high heels she is indeed taller than he is.) They are hampered by being in the front seat of a car together, but it is one of the fiercest out-and-out slugfests between a man and a woman that I can remember ever seeing on the screen.

While her performance is largely understated, Stanwyck is as perfect in her role as she always is. Mason is never so eloquent as he is when his makes his final plea for her love. As for Ava Gardner, is she or is she not the most beautiful woman ever to appear on the Hollywood screen? No wonder James Mason is infatuated with her, like a moth to the flame.

Sun 14 Feb 2010

A Movie Review by MIKE TOONEY:

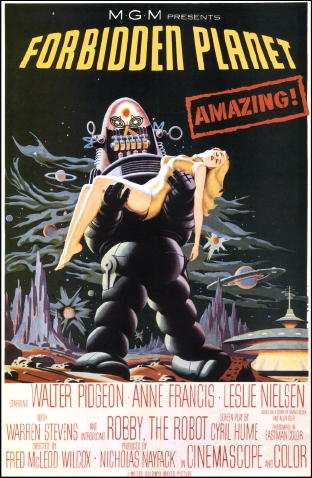

FORBIDDEN PLANET. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1956. Walter Pidgeon, Anne Francis, Leslie Nielsen, Warren Stevens, Jack Kelly, Richard Anderson, Earl Holliman, George Wallace, James Drury, Robby the Robot. Screenplay: Cyril Hume. Story (credited): Irving Block and Allen Adler; (uncredited): Bill Shakespeare and Arthur Conan Doyle. Director: Fred McLeod Wilcox.

As the deep space cruiser C-57D approaches the planet Altair 4, the captain, J. J. Adams (Leslie Nielsen), receives a radio message from Dr. Edward Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) not to land; but Morbius offers no explanation valid enough for Adams to leave, so he sets his ship down.

The main reason the C-57D has come to Altair 4 is to determine the fate of another spaceship, the Bellerophon. Morbius’ account of what happened to the Bellerophon — that it was destroyed by some unknown force while attempting an ill-advised takeoff, killing everyone except Morbius, his wife (who later died), and his daughter — just doesn’t ring true to Adams’ skeptical ears, and he decides to investigate further.

It isn’t long before this “unknown force” is roaming abroad once more. It leaves deep footprints in the sand, warps thick metal steps, and makes salsa of the ship’s communications officer. Eventually it reveals itself in a frontal assault on the C-57D, “as big as a house” and able to absorb billions of volts of plasma energy from the ship’s heavy weapons.

However, as Commander Adams won’t learn until it’s almost too late, the murderous thing he has just fought against isn’t really the one who destroyed the Bellerophon. No, the killer he’s seeking is all too human ….

So much has already been written about Forbidden Planet that I won’t waste any time on the great visual effects (including Anne Francis), the mind-boggling concepts (such as the Krell and their Great Machine), the unique musical score, or the leaden direction.

Instead, let’s very briefly explore the notion that Forbidden Planet is a detective film, much like Them! (reviewed earlier here ), with Sherlockian overtones.

Not only are the wonders of the Krell civilization revealed to Adams, the ship’s doctor (Warren Stevens), and his exec (Jack Kelly), but these marvels have the practical effect of being diversions that take their attention away from the true killer.

Like Sherlock Holmes, however, Adams never loses sight of his mission: to determine what happened to the previous expedition, despite all the razzle dazzle. Much like that legendary Hound haunting the moors of western England, there is a serial killer loose on Altair 4, and Adams aims to catch him.

At every opportunity, Adams returns to the Bellerophon’s fate. Each time the monster goes on the prowl, it confirms his convictions that, despite every obvious indication, people have died due to a human agency, one that is beset by human foibles like fear and jealousy and pride — and since there are only two humans presently living on Altair 4, Adams must choose between someone he admires and someone he loves.

So what we have here — Robby the seemingly harmless robot, an analogue of a certain family retainer; a rampaging monster not dissimilar to the Hound of the Baskervilles; and a monomaniacal scientist ostensibly absorbed with his studies, the Krell this time instead of butterflies on Grimpen Mire — are all familiar elements of detective fiction that in the past usefully served a certain Scottish mystery author as both plot developments and red herrings.

Therefore, in conclusion it’s possible to view Forbidden Planet as more than a sci-fi movie. It just might be the most intellectually stimulating detective film of all time.

Or maybe not. You decide.

Note: Forbidden Planet is scheduled for broadcast on TCM Friday, February 19th.

Sun 14 Feb 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

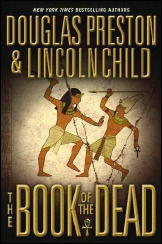

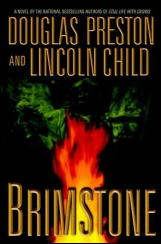

DOUGLAS PRESTON & LINCOLN CHILD – The Book of the Dead. Vision, paperback reprint; first printing, July 2007. Originally published in hardcover by Grand Central Publishing, May 2006.

After I was irretrievably enmeshed in the web of terror skillfully spun by the authors, the friend who had recommended the novel rather off-handedly commented that I probably should have started with the first of the novels in the trilogy, rather than the last. I grumbled a bit at this piece of delayed information but came to the conclusion that I was already enjoying the book so much that I didn’t want to put it aside unfinished.

In any event, the trilogy traces the battle between the two Pendergast brothers, both of them brilliant, one of them a psychopath who will stop at nothing to achieve his aims. The setting of the final confrontation is a favorite of Preston and Child, the New York Museum of Natural History, and details the events leading up to the restoration of a long-sealed Egyptian tomb, culminating in a reception attended by New York’s social and political elite.

A series of horrific murders precede the opening, but they will pale in comparison with the carnage that will result if the plans of the psychopathic Pendergast brother succeed. The plans have been years in the making and the brother who might thwart them is incarcerated in a maximum security prison from which no one has ever escaped.

The authors’ novels tend to be outsize in their concept (and certainly in their length — this book is well over 600 pages), but the gothic imagination that fuels the plots will, if you’re willing to suspend some of your innate disbelief, override all your inhibitions. The novels are the stuff of nightmares, so beware, all you who enter their portals.

The Diogenes Trilogy (Pendergast Novels 5-7) —

Brimstone (2004).

Dance of Death (2005).

The Book of the Dead (2006).

Editorial Comment: Previously reviewed by Walter on this blog: The Cabinet of Curiosities, 2002, Pendergast #3.

Sat 13 Feb 2010

Reviewed by RICHARD MOORE:

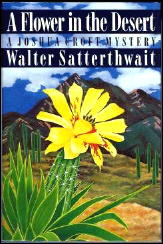

WALTER SATTERTHWAIT – A Flower in the Desert. St.Martin’s Press, hardcover; First Edition, 1992. Paperback reprint: Worldwide, November 1993. Trade paperback: University of New Mexico Press, January 2003.

I’ve always enjoyed Satterthwait’s short fiction but never tried his novels. Bill Crider introduced me to him at some Bouchercon and I picked up this paperback. When a recent trip to Santa Fe came up, I searched for this novel as it is part of Walter’s series featuring Santa Fe private eye Joshua Croft.

Why did I wait so long? Croft hits all my favorite PI hot points. He’s smart and a good investigator but not infallible. He’s a good guy but he’s got a few hangups. Tough but believable.

He’s loyal to his girl friend, who in this book is recovering from a gunshot suffered in an earlier book. No girl Friday, she is a brilliant investigator able to dig up facts on the Internet. Of course, it wasn’t called that then as Al Gore had yet to invent it. In the book, it is called searching the “data base.”

In this book, Croft is searching for the estranged ex-wife and daughter of a Hollywood action star. The woman had accused the actor of child molestation but a judge had found him not guilty. Shortly thereafter, she and their daughter disappeared. The actor, a big Latino star, comes to Croft but he refuses to take the case.

He finally agrees to work for his uncle, an important underworld figure in Santa Fe, who is willing to support her and the child even if she refuses to come out of hiding.

Did she go into hiding to protect her daughter or does her disappearance have something to do with her volunteer work for a group helping illegal immigrants? This is a very satisfying novel and a great hero, and I’ve immediately picked up two more in the series.

The Joshua Croft series —

Wall of Glass. St. Martin’s, 1987.

At Ease With the Dead. St. Martin’s, 1990.

A Flower in the Desert. St. Martin’s, 1992.

The Hanged Man. St. Martin’s, 1993.

Accustomed to the Dark. 1996.

NOTE: Croft also makes an appearance in Lair of the Lizard (St. Martin’s, 1998) a Tony Lowell novel by E. C. Ayres.

Sat 13 Feb 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

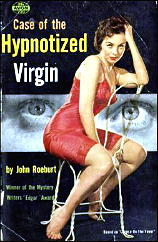

JOHN ROEBURT – Corpse on the Town. Graphic #27, paperback original, 1950. Revised edition: The Case of the Hypnotized Virgin. Avon #730, pb, 1956. Reprinted: Belmont/Tower,1972.

About to check in to his terminal in New York City, cab driver J. Howard Moran, better known as Jigger, agrees to take a trunk to the Railway Express Office. An unknown someone meanwhile has informed the police that the trunk in Jigger’s cab contains a corpse. Which it does, the body of a young woman whose face is battered beyond recognition.

Apparently Jigger. a disbarred attorney in Illinois and a private eye without a license, has investigated other crimes before, though this is his first recorded case. He and his reluctant assistant, Red, “free-lance journalist and improvident writer of plays, features, fiction, columns,” try to determine the woman’s identity and find her killer.

As the police follow Jigger closely with the thought that if they can’t convict him maybe he will be able to pin it on someone else, Jigger manages to come up with the answer.

For his novel Tough Cop, Roeburt won an Edgar, or so the publisher of this novel claims. I have not been able to identify either the category or the year. This one is no prize winner, but it has its amusing moments.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 3, Summer 1992.

Bibliographic Data: It is perhaps no surprise that Bill was unable to discover the category for which John Roeburt won an Edgar, as the publisher’s claim is not true, as he surmised might have been the case.

It may be as obscure as an MWA award can get, and was apparently not for Tough Cop at all. It came in 1949, and it was for Best Radio Drama, the actual title of which I have not discovered, even with the resources available to me on the Internet. It was, however, for one of the episodes of the Inner Sanctum series. (I do not believe that it was for the entire series, but perhaps I am wrong about that.)

Bill erred in saying that Corpse on the Town was Jigger Moran’s first recorded case. Not true; it was his third and last. The first two were published in hardcover; only Corpse was a paperback original:

The Jigger Moran series — [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

Jigger Moran (n.) Greenberg, hc, 1944.

There Are Dead Men in Manhattan (n.) Mystery House, hc, 1946.

Corpse on the Town (n.) Graphic, pbo, 1950.

« Previous Page — Next Page »