November 2010

Monthly Archive

Tue 9 Nov 2010

Comment on FIFTY FUNNY FELONIES

by David L. Vineyard

A funny thing happened on the way to the post …

Most of you have had your own ISP nightmares so I won’t bore you with mine, but because of the down time between your comments on my Fifty Funny Felonies and my getting back to it, Steve suggested I do a post rather than bury my comments at the end of the original.

First, I’m gratified with the responses, and the only thing I would point out to any of you is that I warned from the start my choices were subjective and favorites instead of bests. Almost every name everyone mentioned could easily have been on the list, and in some cases nearly were.

In the end I tended to go with some more offbeat choices and a few certainly more eclectic ones, but only because if you don’t, these lists can easily end up nothing more than a rehash of the same titles; a bit like those AFI 100 Best specials that always end up with Citizen Kane, Gone With the Wind, Casablanca, and The Wizard of Oz in some variation of the top five films.

Among the writers I was surprised no one brought up were Michael Bond of the Monsieur Pamplemouse books, Robert Barr’s Eugene Valmont stories, Agatha Christie (in Tommy and Tuppence mode), Michael Avallone (who granted was sometimes unintentionally funny — at least I think it was unintentional), and Damon Runyon.

As Steve pointed out in one of his comments these could easily run to five hundred titles in short order.

There was one deliberate omission on my part. And please be gentle — but I just don’t like Ross H. Spenser that much. I found it a one joke gimmick that was amusing one time, and after that the books more annoying than clever. Again that is a subjective judgment.

I didn’t find him.

That funny.

Really.

I probably would have included Robert Barnard, Simon Brett, Colin Watson, or Sarah Cauldwell, but it has been a long time since I read them, and they just weren’t fresh in my mind. As it is I have no excuse for leaving off some of Michael Gilbert, Peter Dickinson, certainly John Mortimer, Jasper fforde, Liz Evans (I even reviewed one of her books), or some of the others. As I said, at different times I might have gone with some different writers.

In regard to Geoffrey Household, since his favorite form of novel is the picaresque (a la Don Quixote, Candide) and at least one of his short stories was filmed as the delightful British comedy Brandy For the Parson (1952) I was surprised there was any question about including him.

Many of his short stories (and he did at least four collections of them) are humorous, and there are humorous elements in many of his books. Granted there aren’t a lot of laughs in Rogue Male, Watcher in The Shadows, or Dance of the Dwarfs, but Fellow Passenger, Olura, and The Life and Times of Bernardo Brown are all picaresque tales and there is some rather black humor in A Rough Shoot, A Time to Kill, and The Courtesy of Death.

Victor Canning and Eric Ambler aren’t generally laugh riots either, but both wrote some comic works. Graham Greene is one of the few writers who was ever tragic and comic at the same time in the same book.

I was a little surprised no one questioned my choice of Allingham’s Sweet Danger, so I’ll defend it anyway. The opening sequences in the French hotel are as good as anything in a classical farce. That’s the whole defense.

So there.

Re Edmund Crispin and why Love Lies Bleeding, I grant it is not as farcical as some of the others, but it is my favorite because it includes one of the great dogs in the literature, a creation of Falstaffian complexity, whose passing may be one of the rare times in any kind of fiction you will be laughing and crying at the same time.

I grant The Blind Barber is funnier than Arabian Nights, I just happen to like the latter and think it gets less attention than it deserves. If nothing else it is worth reading just to see Carr’s portrait of what he considers a sexpot.

For that matter a few of the Carter Dickson are probably bigger belly laughs than any of the Fell novels. Sir Henry Merrivale’s summation to the jury in The Judas Window is one of the high points of Carr-ian humor.

I seriously debated 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith, so count yourselves lucky.

In regard to Jonathan Latimer I don’t disagree with Curt’s points about the necrophilia, sexism, and racist language in Lady in the Morgue, but much of that went part and parcel with the whole screwball school of the hard boiled mystery and many of its proponents like Richard Sale, Norbert Davis, Geoffrey Homes, Cleve Adams (at least in the Rex McBride books), Robert Reeves, Dwight Babcock, and Robert Leslie Bellem worked similar territory.

Since Latimer didn’t have to deal with pulp prudery he went farther than most and pushed the boundaries, but it’s honest writing, it feels real and not contrived, and “readers were supposed to be shocked.”

I know that may seem far removed from today’s market where almost nothing is shocking any more (Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho — a black comedy most took seriously — is a rare exception), but once upon a time there were writers who dared to dare us — to shock, titillate, and even challenge us — and Latimer was one of the best, and did within the framework of some first class detective work too.

I would only point out that Curt’s reaction was exactly what Latimer wanted much as Chandler would use a rough rather black and grim humor to color his stories and novels. Both writers wanted the reader to notice “the tarantula on the angel food cake.” It’s a very American tradition that goes back to Washington Irving and Poe and is notable in Mark Twain. In some ways it is the American literary voice.

Again, thanks to everyone for the intelligent and cogent comments and additions. The comic mystery too often gets short shrift in the histories of the genre, as if somehow producing genuine laughs and good detection was simple or easy, and I’ve never understood why. It’s far easier to be grim than amusing, and much simpler to perplex a reader than to make him laugh. These responses show that some of us appreciate the effort.

And on a personal note I find, that while I still appreciate the thrills, puzzles, and scares, the older I get the more I appreciate the ones that made me smile, laugh, or just chuckle in recognition.

Mon 8 Nov 2010

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

GERRY BOYLE – Damaged Goods. Down East Books, hardcover, May 2010.

Genre: Unlicensed investigator. Leading character: Jack McMorrow; 9th in series. Setting: Maine.

First Sentence: I made my way down the trail through the pinewoods toward the house.

Roxanne, the wife of freelance journalist Jack McMorrow has had a worse-than-usual day at work. A social worker for the state of Maine, she was forced to remove two severely neglected children from the home of a Satanist who is now threatening Roxanne and their daughter.

In order to facilitate Roxanne leaving her job, Jack looks for more stories he can sell and finds Mindi, a young woman advertising to provide “companionship.†Mindi quickly becomes more than a story and it’s uncertain whether that is going to increase the danger to Jack’s family.

I’ve missed Boyle’s Jack McMorrow and am very glad to see him back. While Jack, a journalist who isn’t afraid of physical violence, is an interesting character, his neighbor Clair, a Vietnam vet who has lost none of his edge, comes through as the more interesting character, especially when set off by his gentle wife, Mary.

Jack’s wife, Roxanne, is one I’m not always certain I like, but her reactions are very realistic in view of the situation. The blending of all the characters is very well done.

Boyle’s love of Maine is apparent as shares with us both the beauty and the problems of Maine. The story is has a good, tight plot and is layered with good suspense which escalates as things progress. The sense of anger and danger is there along with Jack and his friend’s protectiveness. The villain is satisfyingly nasty and while Mindi provides a somewhat unknown quantity element.

It’s altogether quite well done. Boyle is a very good writer and journalistic background is very apparent. His books are ones I always recommend and I’m always anxious for the next one out.

Rating: Good Plus.

The Jack McMorrow series

1. Deadline (1993)

2. Bloodline (1995)

3. Lifeline (1996)

4. Potshot (1997)

5. Borderline (1998)

6. Cover Story (1999)

7. Pretty Dead (2003)

8. Home Body (2004)

9. Damaged Goods (2010)

Also by Gerry Boyle: The Brandon Blake mysteries

1. Port City Shakedown (2009)

Visit the author’s blog here.

Mon 8 Nov 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE COMING OF AMOS. Cinema Corp. of America/PRC, 1925. Rod La Rocque, Jetta Goudal, Noah Beery, Richard Carle, Arthur Hoyt, Trixie Friganza, Clarence Burton.

Screen adaptation: James Ashmore Creelman & Garrett Fort from the novel by William J. Locke. Director: Paul Sloane; producer Cecil B. DeMille. Shown at Cinevent 42, Columbus OH, May 2010.

This is the perfect Saturday matinee movie, with a climax in an island castle where the heroine (Jetta Goudal) is imprisoned by her villainous husband Ramón Garcia (Noah Beery) in a basement rapidly filling with water.

With a Russian Princess and a noted portrait painter (the hero’s uncle) figuring in the cast, and a ’20s jet set crew of party-loving characters, there’s ample reason to crowd the screen with lavish sets and fantastic costumes, especially when an important scene takes place during a joyous carnival.

The hero is naive but persistent, the heroine beautiful and constantly in peril, and the smirking villain doing everything but twirl his nonexistent moustache.

There are touches of humor throughout, with some witty satire, the sharpest of which is the portrayal of two French policiers as consummate bureaucrats, stopping every other minute as they lead the “chase” into Garcia’s lair to take notes of the information they’re being given.

This is a matinee film for adults, but the kid in the fun-loving viewer will have a grand time, too.

Editorial Comment: This film is available on DVD, but be aware that two of the three reviewers on Amazon disagree noticeably as to the quality of the print.

Mon 8 Nov 2010

Posted by Steve under

General[3] Comments

A NOTE ON THE WORD “DETECTIVE” by Victor A. Berch

It has often been surmised by the critics and historians of detective fiction that had the word “detective†been in use in 1841 when Poe’s “The Murders In the Rue Morgue†appeared in the April issue of Graham’s Magazine, Poe might have used that word to describe his character, G. Auguste Dupin.

In fact, John Ball in his essay “Murder At Large†in The Mystery Story (Del Mar, CA., 1976) states the following:

“In 1843/44, Sir James Graham, the British Home Secretary, added a new and pungent word to the English language. He selected a few of the most capable and intelligent officers of the London Police, formed them into a special unit and called them the detective police. It is regrettable that the word “detective†had not been coined a little sooner, as Poe could have made good use of it.â€

This concept had probably been fostered by the fact that the earliest recorded use of the word cited by the Oxford English Dictionary places it in Chamber’s Edinburgh Journal, vol. XII, p.54 of the March 4, 1843 issue

However, the use of the word “detective†can be documented to have appeared in print before the example given by the Oxford English Dictionary. I first encountered an earlier use in The Examiner #1787 (April 30, 1842), pp. 283-284, which is hereby produced in part:

“EFFICIENCY OF THE METROPOLITAN POLICE…. Now that the preliminary investigation into the facts of the murder at Roehampton(*) have been brought to a close by the committal for trial of the supposed murderer and other persons alleged to be implicated in the tragic affair, public attention has become directed to the circumstances of the case, as most materially affecting the important question, whether or not, the metropolitan police are at all effective as a detective police.

“It has long been manifest to persons acquainted with the principles upon which the government of the metropolitan force is directed, that the officers, although most useful as a preventive force, are most inefficient as a detective police….â€

The article goes on to expound the inefficiencies of the metropolitan police in the handling of this case, and towards the end states that “we think quite enough has been given to prove that the existing system of police is not a detective one, and that unless some most important alterations are made by the appointment of a detective police, or an improvement in the system, the perpetrators of crimes, however horrid and revolting in their nature, will in nine cases out of ten, escape the hands of justice.â€

Although this use of the word detective only pushed the date back by not quite a year, it was not enough to warrant a claim that Poe could have used the word.

My next encounter with the word would prove that it could have been used by Poe. It is in the form of a letter to the editor of The Times (London), May 30, 1840, p. 6; and the entire letter is hereby reproduced because of its importance not only to show that the word was in existence at this early time, but it lays the groundwork for the formation of a “detective police†force:

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES

“Sir, — I observed with much pleasure, in the leading article of your excellent journal a few days back some most able, judicious and temperate remarks on the efficiency of the metropolitan police as a preventive force, and upon its total and unequivocal failure as a “detective policeâ€; the last proposition having been so clearly, but unfortunately too truly demonstrated by the recent dreadful murders and extensive robberies which still remain undiscovered.

“It will hardly be necessary for me to say how fully I accord with every sentence contained in that important article as the public, I believe, have with one voice agreed to its truth and justice, and in the necessity of some immediate remedy. And, further, I am induced to think that the authorities at the Home-office are fully aware that some alteration must take place.

“No one, I think, can for a moment doubt but they must see, however reluctant they might be to admit the fact, that they have most unadvisedly and hastily destroyed a system of detective police, which I may almost say, I am old enough to have witnessed the program from the crude and imperfect system originated by Sir John Fielding, down to the time of that active and able chief magistrate, Sir Frederick Roe, and which system was so much indebted to the great talents and judicious arrangements of the late much-lamented and highly respected, John Stafford, that I may say it had, with the limited force then under his control, reached almost perfection in the meaning of detecting the most artful, extensive and desperate offenders.

“I now, Sir, at once proceed to offer, for the consideration of the Secretary of State, the only means to retrace the unfortunate steps which have induced all classes of society to feel that no means now remain of detecting great offenders, and that their lives and property are no longer safe, with similar with similar and that sooner or later the plan I now suggest, or something like it, must be adopted. The public will demand it.

“I would suggest that 25 or 30 of the officers of the metropolitan police be selected with the greatest care and attention to their activity, talent and integrity, to form a detective force only, and that it would be advisable that to this body some few of the most active, able and respectable of the unemployed police-officers should be added, who might by their great skill and local knowledge render most important information and assistance.

“This detective force should, of course, be under the direction of the Secretary of State and the Commissioner of Police. They should not wear a uniform unless it was thought necessary for them to do upon state occasions or Royal processions. They should report their proceedings to the Secretary of State or the Commissioners of Police only, and that they should have power to call in the assistance of any other part of the force, when necessary, upon their own responsibility.

“The pay of these men should be the same, as the inspectors now have, with similar emoluments when employed to what the officers of Bow-street formerly received under the sanction of the Secretary of State. The first ten of them, as the most efficient, should be first employed on all important occasions either in town or country; the remainder would be employed as circumstances might require, and as vacancies might occur by death or removal.

“This part of the force would always be looked up to as a desirable promotion and reward for men of talent and integrity; these men should not be required to do any of the ordinary patrol duty of the other part of the force, but be allowed to employ their time in the investigation and detection of offences according to their discretion. Making their daily report of what business they are engaged in when in London, in a book to be kept by the chief clerk, for the information of the Commissioners or Secretary of State only.

“I fear these remarks have run into some length, or I should have gone into detail upon many other points, was I not aware that the moment such a plan is adopted .it will speak for itself. Trusting that the importance of this subject will be a sufficient apology for my requesting its insertion in your columns.”

I remain sir, your obedient servant,

DETECTOR

Thus, it is evident that the word detective did exist in print prior to 1841 and may well have been used in everyday parlance prior to the example given above.

(*) This is in reference to the David Good case (1842), details of which can be found in Martin Fido’s Murder Guide to London (Chicago, 1990), as well as in Colin Wilson’s Encyclopedia of Murder (New York, 1962).

© November 8, 2010, by Victor A. Berch

Sun 7 Nov 2010

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

PETE HAUTMAN – Drawing Dead. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1993. Paperback reprint: Pocket, 1997.

Joe Crow is an ex-cop, and an ex-coke head, and an ex-husband, too. Matter of fact, most of his life is ex-; he’s sort of at loose ends professionally and financially, not doing much of anything but playing poker and drifting along.

He’s got sort of a relationship with another ex-coke head, an entertainment agent. Joey Cadillac, down in Chicago, doesn’t have any identity problems — he’s a minor league wiseguy, with a car dealership selling cars mostly to people who need to launder cash.

Joey’s just been ripped off on an old comic book scam, and he’s pissed. He sends a legbreaker to Minneapolis on the trail of the two scammers, who have another deal working with a stockbroker there who happens to play poker with Crow. They know his wife, too, a pheromone-emitting lady named Catfish. Yep. Then they all begin to converge.

This is a jim-dandy first novel. It reminds me of Leonard and Westlake, and maybe just a little of Hiaasen. Hautman has a good ear for dialogue, and a good eye for the kind of people who have been knocked around somewhat.

He tells the story from a number of different viewpoints, and keeps it moving right along. Crow is an interesting lead, competent enough to like but no superman. There is a lot of good stuff about poker and comics, and it’s credible for a change.

This is my kind of book.

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #10, November 1993.

Editorial Comment: Pete Hautman’s book The Prop (2006) was profiled on this blog when it was nominated for Best Private Eye Paperback Original of the Year in 2007.

While Joe Crow did not appear in The Prop, a list of his appearances since his debut in Drawing Dead can be found in this previous post.

Sun 7 Nov 2010

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

STEPHEN PAUL COHEN – Island of Steel. Morrow, hardcover, 1988. Paperback reprint: Avon, 1989.

Stephen Paul Cohen, a real estate lawyer now living in Minneapolis, introduced Eddie Margolis in Heartless, not read by me. Eddie now returns in Island of Steel.

Here he’s working for the Charles Murphy Detective Agency, even though he has no experience in investigation and his boss is almost never around. To top this, he’s assigned to find a real estate lawyer who’s missing from the prestigious New York firm of Fenner, Covington & Pine.

Why would an upwardly mobile attorney go out for cough drops one afternoon and never return? Could it be fatal to find out?

Nicely peopled, nicely plotted, nicely tensioned, a pleasure to read.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 2, Spring 1989.

Bibliographic Data: There were, as it happens, only the two adventures of Eddie Margolis. In terms of crime fiction, Cohen later co-authored a near-future thriller, Night Launch (Morrow, 1989), with then Senator Jake Garn, and on his own, a paperback novel entitled Jungle White, published only in Thailand.

Mike Grost has a short section on Cohen on his Classic Mystery and Detection website. He says in part, “Cohen has considerable poetic skills of description. Both novels seem to be epic poems, an Iliad and Odyssey set in modern New York City.”

Sat 6 Nov 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

My recent experience with the first Continental Op story (related here ) took me on a sort of Hammett binge which brought me to the collection of his Lost Stories (Vince Emery Productions, 2005).

There are 21 tales in this book, but most of them don’t qualify as crime fiction, and those that do are familiar to many of us in the somewhat shorter versions published by Fred Dannay, first in various issues of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and then in the Hammett paperback collections he edited.

Seventeen of the 21 date from Hammett’s earliest years as a writer, 1922-25, when he hadn’t yet developed his distinctive style. Only in “Night Shade†and the non-criminous but fascinating Hollywood tale “This Little Pig†(Collier’s, March 24, 1934) do we find the Hammett we know from his five superb novels.

“Night Shade†first appeared in the debut issue (October 1933) of Mystery League, which was founded and edited by Fred Dannay and Manny Lee and folded after four months. But there are other links to Queen in these pages. The 21st and last of the Lost Stories is “The Thin Man and the Flack†(Click, December 1941), which almost certainly was not written by Hammett.

This throwaway is not so much a story as a stunt to promote the “Thin Man” radio series, with photographs of various actors pretending to re-enact key scenes. One suspect was played by a little-known actress named Kaye Brinker. A few months later, while appearing in an episode of the Ellery Queen radio series, she met and began dating Manny Lee. They married in July 1942 and the marriage lasted until Manny’s death in 1970.

A special plus of Lost Stories for Queenians is that we get to see her as she looked around the time she joined the Queen family. In 1948, during the Queen program’s last few months on the air, Brinker took over as Ellery’s secretary Nikki Porter, which makes her the last actress to play that role in any medium.

Not that many readers of this column are likely to read Chinese, but a small publisher from that country recently contracted with me to issue a modest-sized book called Ellery and Queen containing a number of my essays on EQ.

This volume will include a few paragraphs I’ve written directly for translation into Chinese, discussing the 11-book series of mysteries that was aimed at a juvenile audience and published as by “Ellery Queen, Jr.†All except the ninth and tenth featured Djuna, the houseboy character from the early Queen novels, and share a title pattern — The (Color) (Animal) Mystery — derived from the pattern Fred and Manny had used from The Roman Hat Mystery (1929) through The Spanish Cape Mystery (1935). All eleven were ghost-written. Fred had nothing to do with them but Manny seems to have edited and supervised them.

The first eight titles in the series were The Black Dog Mystery (1941), The Golden Eagle Mystery (1942), The Green Turtle Mystery(1944), The Red Chipmunk Mystery (1946), The Brown Fox Mystery (1948), The White Elephant Mystery (1950), The Yellow Cat Mystery (1952) and The Blue Herring Mystery (1954).

All of these except Golden Eagle and Green Turtle were written by Samuel Duff McCoy (1882-1964), a well-known journalist of the early 20th century whose papers are archived at his alma mater, Princeton University, and include many documents related to his work as “Ellery Queen, Jr.â€

As Samuel Duff he was the author of “The Bow-Street Runner†(EQMM, November 1942), a historical whodunit—narrated in first person by a Cockney — which was one of the earliest original stories to appear in the magazine Fred had founded in 1941.

The author of Golden Eagle and Green Turtle was Frank Belknap Long (1901-1994), a specialist in pulp horror fiction, whose correspondence with fellow horror maven August Derleth includes statements that he wrote two of the series, although he doesn’t mention the titles.

After an eight-year hiatus in “Ellery Queen, Jr.†titles, Golden Press issued The Mystery of the Merry Magician (1961) and The Mystery of the Vanished Victim (1962), both featuring Ellery’s nephew Gulliver Queen as youthful sleuth.

These and the eleventh and final entry, The Purple Bird Mystery (1966), were apparently written by James Holding (1907-1997), an advertising executive who turned to writing mystery novels for juveniles after the tragic death of his son. But on at least one occasion Holding seems to have employed a second-order ghost to do the work for him, and Manny Lee went livid when he found out.

Among adult readers Holding is best known for two series of short stories in EQMM, one (1962-70) featuring professional assassin Manuel Andradas, known as The Photographer, the other (1960-72) following two mystery writers, the creators of fictional sleuth Leroy King, as they solve “real†crimes while on a world tour. The titles of these tales, from “The Norwegian Apple Mystery†to “The Borneo Snapshot Mystery,†employ the familiar pattern of the early Ellery Queen novels.

By the time The Purple Bird Mystery came out, Pocket Books was publishing the last of the 15 original paperback novels signed as by Ellery Queen but, as has long been known, ghosted by others under Manny Lee’s supervision.

During those years Pocket was also using another Dannay-Lee byline, Barnaby Ross, for six historical novels beginning with Quintin Chivas (1961) and ending with The Passionate Queen (1966).

All six were written by Don Tracy (1905-1976), the author of a number of thrillers and historicals under his own name, including several published by Pocket Books. Whether Manny Lee supervised these as he had all the ghosted Queen books is uncertain. He and Fred must have received some money under this arrangement.

But why did the publisher bother to pay them anything? It can’t be coincidence that, during the same years Pocket was issuing ghosted paperbacks as by Ellery Queen, it was also putting out another line of softcovers under another Dannay-Lee byline.

As far as I can tell, Pocket never made the slightest attempt to lure potential readers into identifying the byline on these six historicals with the byline on the four Drury Lane detective novels of 1932-33. What would have been the point?

If there was no point, why not just publish all six as historical adventures by Don Tracy, without the Barnaby Ross byline and without having to pay Fred and Manny for its use? Perhaps someday the business correspondence dealing with these books will be unearthed and allow us to understand a sequence of events which on its face makes no sense.

Many years ago I made myself read one of those historicals. One was quite enough. Never again!

Fri 5 Nov 2010

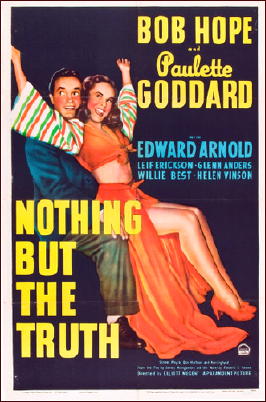

NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH. Paramount Pictures, 1941. Bob Hope, Paulette Goddard, Edward Arnold, Leif Erickson, Helen Vinson, Willie Best. Director: Elliott Nugent.

A funny movie needs a funny premise, I’d have to say and I hope you agree, but is a funny premise enough to make a funny movie?

Bob Hope, playing Steve Bennett, a new partner in an investment firm, is inveigled into making a $10,000 wager that he can tell the truth, and nothing but the truth, for the next 24 hours. The rest of the movie, given this rather belabored but still promising beginning, is unfortunately about as predictable as (in general) the rest of movies come.

The three men who are betting against Bob are not above low and mean-minded activities to protect their wager, as you might expect. On the other hand, the money Bob is putting up is not really his to bet, but that of Gwen Saunders (Paulette Goddard), or really the charity she is desperately trying to raise $40,000 for — and you can see how desperate she is, giving the money to someone like Bob Hope with a request to “double it for her overnight.”

As if this were not enough, a showgirl trying to raise money for her Broadway-bound play is also involved. And of course Bob and Paulette Goddard fall in love, even though she already has a strapping young boy friend, one of the idle rich, and one of the guys who made the bet with Bob.

But need I tell you more? I’ve already called the plot predictable, and from here on, you’re on your own. What kind of idiot situations could you think of? Most of them (I’ll wager) will be in here.

Is the movie funny? Bob Hope made me laugh, but between you and me, nobody else did, with the possible exception of Willie Best, who plays Bob’s personal valet in what’s really a rather demeaning role. (You could say that at least it was a role, which all too few blacks had in movies made in 1941, but it is highly unlikely that roles such as this did anything to improve the lives of blacks in this country.)

Paulette Goddard, however, is bright and spritely and sparkling in this movie, and if somebody can tell me why her career went downhill after this, and not onward and upward, I’d surely appreciate learning about it.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File #35, November 1993, revised but not substantially.

[UPDATE] 11-05-10. This movie was recently released on DVD in a box set called Bob Hope’s “Thanks for the Memories Collection,” and I’ve just put it into my Amazon shopping cart.

Arguing with myself on the merits of an old film I saw (and taped) on TV this many years ago is probably futile, but I have a feeling that if I watched again, I might enjoy it a lot more than I did this first time around. Comedy and humor are funny things (and you can quote me on that).

As for Paulette Goddard, I didn’t have the luxury of the Internet to help me out when I first wrote this review. Even so, while pointing out that she was nominated for Best Actress in a Supporting Role for So Proudly We Hail! in 1943, IMDB only says that “her star faded in the late 1940s […] and she was dropped by Paramount in 1949,” when she was still only 39.

Thu 4 Nov 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

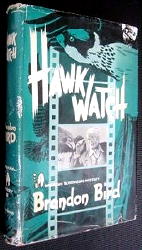

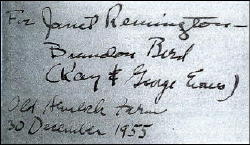

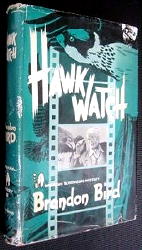

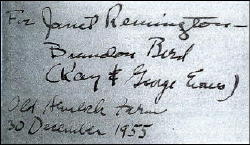

BRANDON BIRD – Hawk Watch. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1954. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, August 1954. UK edition: T. V. Boardman, hardcover, 1955 (shown).

Kay Harris and George Bird Evans wrote four mysteries under the Brandon Bird pseudonym, but this was the first of their books I had encountered. I bought it for two reasons: it was cheap and it was signed by the authors.

Charles Gratton, a professional photographer, is on assignment in the West Virginia mountains to capture the hawk in flight. The hawk proves an elusive subject but a predatory Golden Eagle that attacks and kills a dog belonging to his local guide, and a mysterious figure Gratton catches watching him through binoculars, bring him into a situation far more daunting — and dangerous — than his hawk assignment.

This entertaining mystery makes good use of the remote rural setting, a captivating heroine, and a reclusive, canny, murderous antagonist.

Hubin lists three other mysteries by Bird, Downbeat for a Dirge, Never Wake a Dead Man, and Death in Four Colors. All three feature Hampton Hume, his wife Carmela, and Ruff, their their “faithful” English setter, Ruff.

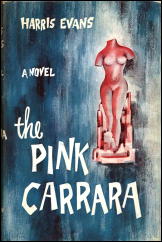

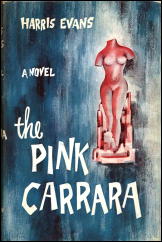

The last recorded appearance in Hubin for the Evans’ novels is for The Pink Carrara, written under the nom de plume of Harris Evans, and published in 1960 by Dodd Mead.

My enjoyment of Hawk Watch and the intriguing titles of the three other Bird titles led me to do a bit of sleuthing on the Internet, where I came up with a number of hits for George Bird Evans.

He was born in Uniontown, Pennsylvania (a town not far from Pittsburgh) in 1906 and studied art at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon) in Pittsburgh, where he met his future wife and co-author, Kay Harris of Wheeling, West Virginia.

After studying at the prestigious Chicago Art Institute, George (now married to Kay) moved to New York City, where he had a successful career in magazine illustration, eventually landing a contract to illustrate mystery fiction for Cosmopolitan Magazine.

In 1939, the couple left Manhattan and moved to a farm they had bought in Preston County, West Virginia, a pre-Revolutionary building they immediately began to renovate. George continued to do magazine illustrations until the 1950s, when the two, both voracious readers, began publishing their pseudonymous mysteries.

Although I’ve not been able to consult a copy of The Pink Carrera, I found a listing on ABE that described it as “a novel about a portrait sculptrist and his need to do art to support his pink carrara.” (Carrara is a city in Northern Italy famous for the white marble that was favored by Italian Renaissance sculptors.)

A signed, limited edition of all five of their novels was published as “The Old Hemlock Mysteries” in 1995. This omnibus suggests that the crime elements in The Pink Cararra are stronger than described above.

George Evans, an avid sportsman from childhood, became nationally known as a breeder of bird dogs and was a frequent contributor to Field & Stream and Pennsylvania Game News.

Late in his life, Evans apparently came to regret his contribution to overhunting that had led to a substantial decline in the numbers of native game birds, and began to lobby against the practice. After George’s death in 1998 and Kay’s in 2007, the Old Hemlock Foundation was established on their West Virginia farm with a number of objectives that include environmental protection, support of the local Humane Society, and the awarding of scholarships to the WVU Medical School.

[UPDATE] 11-07-10. Jamie Sturgeon has kindly sent me a cover image for the British edition of The Pink Carrara, along with a full description of the story, taken from the inside flap of the dust jacket:

“This is the story of a man and a woman who loved not wisely but too well. It begins in a sculptor’s studio in New York where a great conductor, Joseph Matulka, has sent his young wife Leslie for a series of sittings.

“Leslie, a brilliant opera singer; Matulka, the musical genius to whom she is married; and Paul Greer, the sculptor, are the three key figures in this situation, filled with tragedy or happiness. As the author develops his story from three points of view, the action progresses.

“A magnificent block of pink Carrara marble, which in the sculptor’s hand takes on a significance he has not realised, gradually becomes the focal point of the story and begins this serious and distinguished novel, with its suspenseful theme, to a dramatic close.”

Other than the phrase “suspenseful theme,” there is not much here to indicate that this is indeed a crime novel. We shall assume that it is, however, unless I can impose even further on Jamie to skim through the book until such time he can definitively say yea or nay.

[UPDATE #2.] 11-08-10. Here’s Jamie’s reply:

“Looking through the book there are 310 pages — the death, an accident, takes place on 276. The musical genius Matulka goes to the sculptor’s studio (with a gun) to have it out with the sculptor about the sculptor and Matulka’s wife. They have a fight and Matulka gets crushed by the pink carrara. There is some business afterwards about hiding the gun but I would say marginal at best.”

Bill Pronzini, in a separate email, has concurred. He had the book at one time and has since swapped it away. “Only marginally a crime novel,” he says, “and for my taste not half as well done as any of the Brandon Bird mysteries.”

The opinions above were duly reported to Al Hubin, who replies: “It certainly looks like it merits a dash [as having only marginal crime content] at least, if not deletion.”

His final decision on the matter will undoubtedly appear in the next installment to the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV.

[UPDATE #3.] 11-09-10. No need to keep you waiting. He’s decided on the dash.

Wed 3 Nov 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

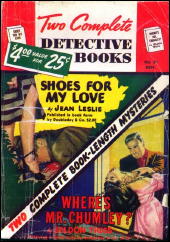

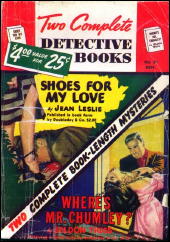

SELDON TRUSS – Where’s Mr. Chumley? Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1948. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1949. Reprinted in Two Complete Detective Books, No. 59, November 1949.

Where indeed is the Reverend Mr. Chumley, curate at Charwell? The police suspect that he is off with an illicit lover, but those who know the good man are dubious, perhaps incredulous. As well they might be, for the unfinished letter to his “lover” turns out to be a forgery.

Under the guise of a commercial gentleman, Chief Inspector Gidleigh, C.I.D., takes charge of the investigation into Chumley’s disappearance and has also to contend with a possible abortionist, a seeming suicide, and the odious Mr. Twigg. Nobody’s fool, Gidleigh gets part of it right.

While Truss is not in the top rank of mystery writers, he (she?) is certainly high in the second tier. Humor, interesting and sympathetic characters, if one does not count the child Maisie of the marbly eyes, and a splendid plot make this novel, as well as others by Truss, worth trying to find.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.

Bio-Bibliographic Data: If (Leslie) Seldon Truss (1892-1990) is not male, I hope someone will leave a comment to let us know. His (I am presuming) writing career extended from 1928 to 1969, and included some 40 crime novels, including one written as by George Selmark.

Inspector Gidleigh appeared in 22 or 23 of these (when one non-Gidleigh book was reprinted, Gidleigh showed up in it as the detective in charge), while Detective Inspector Shane appeared in six and Inspector Bass in yet another three.

[UPDATE] 11-07-10. From Victor Berch comes the following note about Seldon Truss:

“Here is what I’ve managed to gather from a variety of records: Leslie Seldon Truss was the son of George Marquand, an agent for a produce company, and Ann Blanch (Seldon) Truss on August 21, 1892 in Wallington, Surrey, England.

“According to his enlistment record in WW I, he had previously been a film producer for Gaumont Film Co. On the record dated Oct 8, 1915, he lists his age as 23 years and 2 months. He served with the 2nd Scots Guard during WW I.

“He died Feb 5, 1990 at Hastings and Rother, East Sussex, England. He was a member of the Society of Authors and the Crime Writers Association. I think this should clear up his sex gender once and for all.”

« Previous Page — Next Page »