December 2010

Monthly Archive

Thu 16 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.

… Carroll & Graf has also reprinted John Dickson Carr’s historical mystery, The Demoniacs (1962). This is not top-class Carr; the murder method is unconvincing, and there are too few suspects. Also, many characters are given the annoying habit of answering questions with questions.

Still, London in 1757 comes remarkably alive, and we learn a great deal about the famous mercenary thief-takers of the time, through the hero, Jeffrey Wynne, “the only honest Bow St. Runner.” Also interesting is Carr’s description of a massage parlor, written a few years before they became so popular in the sleazy areas of our cities.

Proof of Carr’s popularity is that two other publishers are also reprinting his work. Harper’s Perennial Library has just issued four books, and only one is in any way weak.

The Four False Weapons (1937) is the last and weakest of Carr’s Henri Bencolin series, and it could have used a less muddled solution, as well as a diagram of the hard-to-picture murder house. The characters and their emotional responses are so implausible they prove distracting.

However, Carr is at or close to his best in the three Gideon Fell books from Perennial. The Mad Hatter Mystery (1933) is chronologically the second Fell book, and who can resist its bizarre plot, with top hats being stolen all over London?

One hat turns up on the head of a corpse found in the Tower of London, a building whose physical aspects are important to the plot. The book is also about an unknown Poe manuscript which supposedly predates “Murders in the Rue Morgue.”

Carr even provides this poignant description of the unhappy Poe: “Never in his life would that dark man have anything, but dreams to exchange at last for the cold coin of an immortal name.”

Long ago in these pages (Vol. 2, No.3, May 1978), I wrote an article about Carr in which I described how he usually had a character who embodied much of his own history and traits and acted as Watson to Dr. Fell’s Holmes.

Christopher Kent in another Perennial reprint, To Wake the Dead (1938), is one of Carr’s most appealing of these secondary players, a mystery writer who finds a corpse in a London hotel who turns out to be his cousin’s wife. So strong are Carr’s narrative powers in this book that we accept coincidences we might not take from lesser suspense writers.

The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941) is one of the three best Fell books, high praise indeed. (The very best of the Fells, The Crooked Hinge [1938], was reprinted by Perennial in the summer of 1989 and is still available.)

Constant Suicide’s hero is, like Carr, an American in the British Isles. Alan Campbell’s train journey to Scotland, in which he meets an attractive, mysterious woman (also named Campbell), is a near perfect beginning. The setting, a castle in the Highlands, and the intricate murder puzzle also could hardly be improved upon.

IPL has no fewer than twenty Carrs in print, including nine as Carter Dickson, and I am tempted to take the easy road and merely recommend all of them. Well, I do recommend them all, but I will select some favorites among them:

Seldom have atmosphere and puzzle been more happily married in a mystery than in Hag’s Nook (1933), the first and one of my three favorite Fells. The Three Coffins (1935) is arguably Carr’s most famous book, and because of its famous lecture chapter is probably the seminal work on locked rooms. Though Barzun and Taylor detested it, the exotic Below Suspicion (1949) is one of the best of the “later” Carrs.

It may be sacrilege, but in general I prefer the books Carr wrote as Dickson. The puzzles were as good, and Carr wrote some hilarious scenes of slapstick, usually for the entrance upon the scene of the “Old Man,” as his detective, Sir Henry Merrivale, calls himself.

In He Wouldn’t Kill Patience (1944), my favorite of all Carr’s seventy-plus books, we meet him being chased around the reptile house by a large tropical lizard. This ingenious “locked zoo” mystery is enhanced by a cast of magicians — and the background of London blacked out in the “blitz.”

In The Reader Is Warned (1939) Merrivale solves a murder with impossible elements, though not in a locked room. We also have Merrivale driving a train and hitting a cow. Why is HM driving a train and how did the beast get on the tracks? That’s a bonus to the mystery, if you read the book.

The Gilded Man (1942) is one of the most enjoyable weekend-house-party mysteries ever written. Besides a wild and wickedly clever puzzle, there is Merrivale, as a substitute magician and mixing axioms. “The cat’s been at the spilt milk. There’s none left to weep over.”

One more Carr from IPL must be mentioned, a non-series entry, the justly famous The Burning Court (1937). Ordinarily, when an author introduces elements of the supernatural into a mystery, I shout “Cop-out” and throw the book aside. Carr not only does it in this book, along with some non-science-fictional time travel, but he had me eating out of his literary hand and loving it.

Wed 15 Dec 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

VALENTINE WILLIAMS – The Curiosity of Mr. Treadgold. Houghton Mifflin, US, hardcover, 1937; Grosset & Dunlap, US, hc reprint, no date stated. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hc, 1937, as Mr. Treadgold Cuts In.

Following up on his success in Quebec in investigating what were known as “the Saint Fiorentin murders,” chronicled in Williams’s Dead Man Manor, H. B. Treadgold, head of Bowl, Treadgold, and Flack, bespoke tailors of Savile Row, London, and East Fiftieth Street, New York, continues dabbling in crime investigation by solving ten cases of theft, blackmail, or murder.

“In

Tristram Shandy [from which Treadgold quotes on all occasions], as I’m sure you’ll recollect, it says that body and mind are like a jerkin and its lining: rumple one and you rumple the other. Ill-fitting clothes mean an ill-fitting mind: which is rather a roundabout way of saying that a tailor who takes any pride in his job has to be a bit of a psychologist.”

The cases here are not fair play, by any means, but that does not make them any the less enjoyable. Treadgold is a capable detective and an interesting character.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.

Editorial Comment: Bill’s review is too short, alas, to learn very much about the stories themselves, but it’s certainly long enough to be intriguing. There’s no question that Valentine Williams falls into the category of a Forgotten Writer, but if you’d like to know more, there’s a long essay about him on Mike Grost’s Classic Mystery and Detection website. Recommended!

The Mr. Horace B. Threadgold books —

Dead Man Manor. Hodder 1936. [novel]

Mr. Treadgold Cuts In. Hodder 1937; published in the US as The Curiosity of Mr. Treadgold. [story collection]

Skeleton Out of the Cupboard. Hodder 1946. [novel; no US edition]

Wed 15 Dec 2010

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

ARIANA FRANKLIN – A Murderous Procession. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hardcover, April 2010. Published in the UK as The Assassin’s Prayer: Bantam Press, hardcover, July 2010.

Genre: Historical mystery. Leading character: Adelia Aguilar; 4th in series. Setting: France/Italy; Middle Ages/1179.

First Sentence: Between the parishes of Shepfold and Martlake in Somerset existed an area of no-man’s-land and a lot of ill feeling.

Dr. Adelia Aguilar is thrilled to learn Henry II wants to send her to accompany his daughter Joanna’s wedding procession to her home of Sicily. Her feelings change to anger when she learns Henry is keeping Adelia’s daughter in England to ensure Adelia’s return.

With them, and well concealed, will be Arthur’s sword, Excalibur, as a gift to the bridegroom. Danger a rises from an old foe out to steal the sword and looking for revenge against Adelia.

There was a different feel to this book than those previous. Whereas before, Adelia seemed very much in control and strong, here she was in situations completely beyond her control and, at times, in great peril.

While some readers might not care for the change this wrought in the character, I liked that it showed her vulnerability and weaknesses, as well as the human failing that when the truth is too frightening to accept, it is denied.

There is a progression in the lives of the characters with each book, which is important to me. Some readers have criticized the coup de foudre felt by the Irish sea captain O’Donnell for Adelia. Having personally experienced it — although it didn’t last — I didn’t find it unrealistic. I did enjoy that we meet Adelia’s parents in this book.

As always with Franklin’s books, I learn so much history. Henry’s daughter, Joan, was known to me, but not in any detail nor her role in history. Of late, I’ve read more books that deal with the Cathers, and I find them fascinating. I certainly knew nothing of the history of Sicily and found it significant that she shows it to us at a turning point in its history.

Perhaps I’m obtuse, but I did not figure out the identity taken by the villain until it was revealed. What I did not like was the ending. It seems more authors are doing cliff-hanger endings and it’s a trend I dearly hope will end almost immediately. Write a good book, I promise to read the next one without being tricked into so doing.

I very much enjoyed the story and only the ending prevented my rating it as “excellent.†For readers new to the series, I recommend starting at the beginning. For me, I am ready for the next book.

Rating: Very Good Plus.

The “Mistress of the Art of Death” series: [Adelia Aguilar is the world’s first female anatomist/medical examiner.]

1. The Mistress of the Art of Death (2007)

2. The Serpent’s Tale (2008) aka The Death Maze

3. Relics of the Dead (2009) aka Grave Goods

4. A Murderous Procession (2010) aka The Assassin’s Prayer

Tue 14 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

REVIEWED BY TINA KARELSON:

JOHN DICKSON CARR – He Who Whispers. Harper & Brothers, US, hardcover, 1946. UK edition: Hamish Hamilton, hc, 1946. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including International Polygonics, 1986. (Cover art: Roger Roth.)

Gideon Fell is amusingly absent-minded in this eerily atmospheric novel set in London in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War:

“Waterloo, its curving acre of iron-girdered roof still darkened over except where a few patches of glass remained after the shake of bombs, had got over most of the Saturday rush to Bournemouth.”

This description of the iconic London railway station is the height of the book’s achievement. The solution to the murder, which took place in pre-war France, is also very clever, and there’s a well-made philosophical point to the story about how easily facts can be interpreted differently depending on how one wants — or has been influenced — to see them.

Unfortunately, melodrama and coincidence dominate these finer points. And the psychological point of view is so absurd it must have been ridiculed even when in vogue. A ladylike female character’s fate is tragic because she “had to have men.”

This continues on page 136 with, “In women so constituted — there are not a great number of them, but they do appear in consulting rooms —the result does not always end in actual disaster…” The murderer is neurotic and weak, dominated by his father, and at the same time terribly clever and cruel.

Whatever the clinical facts of nymphomania and neurosis, they’re overblown here to a degree that undermines the narrative.

Tue 14 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

GREGORY MCDONALD – Confess, Fletch. Avon, paperback original, November 1976. Reprinted several times since, in both hardcover and soft. Reviewed in Kindle format.

Fletch arrives in Boston in search of some missing paintings, only to find a naked murdered woman in his newly borrowed apartment. His attempt to find the paintings is complicated by two crazy, manipulative women, and Inspector Flynn who has a habit of showing up at the worst possible moment to ask Fletch if he is ready to confess to murder.

Much like his characters, Gregory Mcdonald was fond of defying convention. When Mcdonald rejected releasing Confess, Fletch first in hardcover, and instead had it released as a paperback, many worried he was devaluing the mystery genre. His reported response was “I like to be read by people.”

Confess, Fletch would win the 1977 Edgar award for Best Paperback Original. It would be the only time the first book of a series (Fletch) and its sequel won back-to-back Edgar awards.

Most books in a series follow the characters in chronological order. Mcdonald ignored Fletch chronology. Confess, Fletch was the second book published in the series, but the sixth in Fletch time lime.

Mcdonald’s fast, almost screenplay-like style, with its smart-ass humor and cynical characters was a perfect reflection of its time. Fletch existed in the time of Robert B. Parker’s Spenser and TV’s Jim Rockford, when characters were more the focus than the mystery and the twists more important than clues.

The book’s greatest virtues are the characters of Irwin Maurice (aka Peter) Fletcher and Inspector Francis Xavier Flynn. With his laid back, irresponsible exterior hiding a strong moral center, Fletch was the stuff heroes were made of in that era. The brilliant, self-effacing sarcastic cop, Flynn was a delightful change from the average fictional cop.

Mcdonald’s well deserved critically praised dialog with its natural shortness drives the pace of the story. Funny, real, misleading at times, Mcdonald often expects the reader to understand the true meaning hidden under what is said. This is especially true when Flynn and Fletch are together.

Locations are described with just the minimum needed to set the scene and keep the story moving. Mcdonald avoids the details of mundane reality and speeds us along focused more on the characters than the mystery. Plot holes pass by like billboards on the freeway. Even should you notice them, you never care enough to slow down to consider them.

Confess, Fletch was not meant to be a masterpiece of deduction, no trip to some exotic location, no dark noir, but instead it is a masterpiece of light mystery set in the world with characters you will never want to leave.

A primary research source for this review was the website ThrillingDetective.com.

Mon 13 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE SINGING FOOL. Warner Brothers, 1928. Al Jolson, Betty Bronson, Josephine Dunn, Arthur Housman, Reed Howes, Davey Lee. Director: Lloyd Bacon. Shown at Cinefest 28, Syracuse NY, March 2008.

This enormous success (and Jolson’s second partially-talking film) is said to have been the biggest box-office grosser until Gone with the Wind, with a worldwide take of almost six million dollars.

The song “Sonny Boy,” written by Jolson’s character for his son, was one of the performer’s major hits and there’s no gainsaying the fact that the song is tremendously effective in the film.

Jolson’s over-the-top performance is a bit hard to take, with a sentimental plot (Jolson marries a gold-digger instead of the true-blue girl who loves him, and when his wife leaves him, taking their son with her, he falls apart) that has him on-screen for a recorded 106 minutes that somebody took the time to clock.

That’s a lot of anybody and for such an over-the-top performer as Jolson, too much for one sitting. Or even two or three.

Mon 13 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

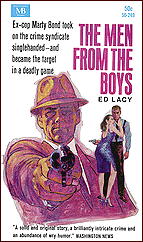

ED LACY – The Men from the Boys. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1956. Paperback reprints: Pocket #1152, 1957 (cover art by Lou Marchetti); Macfadden 50-249, 1967.

One of the chief pleasures of going to PulpFest (aside from observing the antics of Steve and Walter from a safe distance…) is finding something I saw on a bookstand years ago and didn’t get for some reason — probably because I was broke at the time. This year it was The Men from the Boys (the Macfadden paperback you see to the left) and I’m glad I finally got back to it.

This is the goods. Originally published in 1956, this fast, tough and faintly poetic tale is the first-person account of Marty Bond, a disgraced ex-cop living in a seedy hotel on his pension and whatever he can get as house detective, pimp, bouncer, and resident chiseler.

As the story starts, he’s visited by his stepson Larry, a cop-wanna-be and Citizen On Patrol who answered a call for help from a neighborhood butcher claiming he was just robbed of fifty thousand dollars. Only when Larry got back with a real cop, the butcher decided he hadn’t been robbed at all.

From this intriguing start, Lacy goes on to spin a tale of mobsters, prostitutes, patsies and fall guys, with an occasional mostly-honest cop and aspiring stripper thrown in, set against a backdrop of New York in a sweltering summer. And when Lacy swelter, you can feel your shirt stick to your back.

The action scenes are plentiful and well-handled, the characters vivid and memorable, and if the central puzzle turns into something disappointingly impossible, well, it’s easy to forgive in an ending that surprised me with its off-the-wall poetry.

I’ll be seeking out more by Lacy, and meantime, this one stays on my shelf for years to come.

Editorial Comment: For a long overview and profile of Ed Lacy and his career, check out Ed Lynskey’s article here on the main Mystery*File website. It’s followed by a complete bibliography of his book-length fiction.

Sun 12 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY J. F. NORRIS:

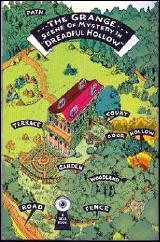

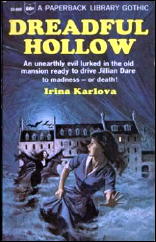

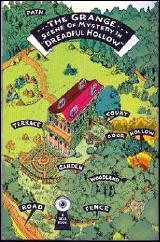

IRINA KARLOVA – Dreadful Hollow. Hurst & Blackett, UK, hardcover, 1942. Vanguard Press, US, hardcover, 1942. Reprint paperbacks include: Dell #125, 1946; Paperback Library 53-860, 1965; 2nd pr., 64-030, 1968.

This gothic supernatural novel with detective novel elements wavers between genuinely creepy and outrageous self-parody. At the time I was reading it I wondered if Karlova is a pseudonym for some better known writer. The name seems influenced by Universal horror movie characters and actors. I later learned that I was correct.

The author’s real name is Helen Mary Clamp (sometimes noted as H.M. Clamp), and she was extremely prolific throughout her lifetime. In addition to writing three supernatural novels using the Karlova pen name, she wrote over 60 novels from main stream to romance to adventure under her given name.

Using yet another pseudonym (Olivia Leigh) she wrote a few more romances and eleven literary biographies on historical figures such as Nell Gwynn, Charles II of Spain and Louis XV. Her writing career lasted from 1925 to 1970.

Dreadful Hollow seems to be influenced by those Universal monster movies I mentioned earlier. It certainly seems to be a bit of a coincidence that those films with all the Eastern European atmosphere and characters should share such a similarity with this book written several years after those films were popular.

It is peopled with Hungarian gypsies, a mysterious countess of either Czech or Hungarian descent, and a stuffed werewolf, and the dread vampire legend looms large over the story.

Although it does borrow a framework from the detective novel in that the two narrators do some digging up of clues and interview servants and neighbors, it really is nothing more than a pulpy, over-the-top horror novel with all the usual HIBK trappings of the neo-Gothic novel.

The major difference is that whereas most of those books are pale imitations of a Gothic novel, Karlova’s book is indeed a true Gothic. She does very well with all the Radcliffian elements – emphasis on dreary landscapes and decaying households, a real femme fatale, a ninny of a heroine who suspects she is losing her mind, and genuine supernatural beings and activity.

As I read I also noted that the structure of the novel was probably inspired by Stoker’s Dracula, with the first person narrative journal entries of young Dr. Clyde (who seems to have escaped from the pages of a pulp magazine like Speed Detective — he speaks in an entirely American wiseacre slang) interspersed with the third person limited sections focusing on Jillian Dare, the young girl hired to act as a companion to an ancient crone.

The book is unintentionally funny and the mystery is, sadly, to a modern reader, rather obvious from the opening chapters. When young Countess Vera arrives on the scene, any reader who hasn’t instantly figured out the mystery has probably never seen a vampire movie in his or her lifetime.

That isn’t to say the book is not without its deliciously gruesome surprises. There is a disappearance of a young boy that isn’t fully explained until the final pages, for instance. I have to confess that I was alternately raising my eyebrows, gasping and laughing in the final pages which really do get rather wild and bizarre for a book of this era.

I am sure that even most jaded contemporary reader will find something thrilling in Dreadful Hollow. They certainly don’t write them like this anymore.

A side note: Some additional research turned up several articles on the internet which mention the fairly recent discovery of William Faulkner’s screen adaptation of Dreadful Hollow.

Apparently the find happened sometime in 2001 by his daughter who turned the script over to Lee Caplin, Faulkner’s literary executor. Caplin also happens to be a film producer and was toying with the idea of making the movie. Here’s a link to the news story I found from 2007.

And there is also some mention of the discovery of the script in a article back in the March 2009 issue of The Faulkner Journal: “The Unsleeping Cabal: Faulkner’s fevered vampires and the other South.”

But now in 2010 it seems the whole thing as been scrapped. There is no info on the movie on Lee Caplin’s website for his Picture Entertainment outfit and nothing noted on his page at IMDB — a source I find generally reliable about films in pre- and post-production.

Irina Karlova’s supernatural mysteries:

Dreadful Hollow. Hurst & Blackett, 1942.

The Empty House. Hurst & Blackett, 1944.

Broomstick. Hurst & Blackett, 1946.

Sun 12 Dec 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

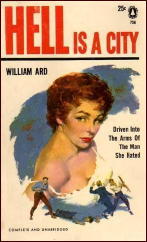

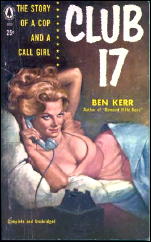

Something unusual happened to me on Thanksgiving morning and I’m thankful that it did. Browsing the Web for something entirely different (and apparently nowhere to be found), I stumbled upon a truly excellent website devoted to that unjustly forgotten Fifties hardboiled author William Ard, who managed to write something like three dozen novels before dying of cancer at age 37. With permission from website proprietor Dennis Miller, I hereby offer a link.

Decades ago, when I was writing the essays about Ard for The Armchair Detective that earlier this year I reorganized into a chapter for my book Cornucopia of Crime, I had had some correspondence and phone conversations with his widow and son.

Mrs. Ard, nee Eileen Kovara, was tremendously helpful, even loaning me her copy of one Ard novel I had never been able to locate on my own and have never seen since.

I learned from Dennis Miller’s website that both had died since I was last in touch with them, but he and I began emailing and I soon had the cyber-address of Ard’s daughter and got in touch with her.

Her father died destitute, she told me, and her mother had a hard time of it for many years, trying to support herself and two children on a secretary’s salary.

I now know a lot more about the Ard estate than I knew before Thanksgiving, and I’m hoping to persuade a publisher I know who loves hardboiled and noir novels from the Fifties to reissue a few of Ard’s, especially Hell Is a City (1955) and Club 17 (1957, as by Ben Kerr). As they say in the news biz, more details later.

In my last column I described how Fred Dannay, reprinting Dashiell Hammett’s first Continental Op story in EQMM decades after its first publication in 1922, tried to make it seem less like a period piece by inflating all the cash amounts and substituting common or garden variety bonds for the original version’s Liberty bonds, which the U.S. had sold to finance its entry into World War I.

This seems to have been a recurring editorial habit of Fred’s, and not even Ellery Queen stories were exempt from its reach. In EQMM for March 1959 he reprinted “Long Shot,†a Queen short story first published twenty years earlier, but changed the names of most of the movie stars who attend the big horse race.

Joan Crawford and Greta Garbo are fused into Sophia Loren, Al Jolson is replaced by Bob Hope, Bob Burns by Rock Hudson, Joan Crawford the second time by Marilyn Monroe, and Carole Lombard by Jayne Mansfield.

The only star who appears in both versions of the story is Clark Gable.

If I hang onto life and health long enough, one of the books I’d love to do is a volume of The Wit and Wisdom of Anthony Boucher.

Here’s a prime candidate for inclusion, from a letter of his to Manfred B. Lee of the Ellery Queen partnership, dated February 9, 1951.

As the Forties segued into the Fifties and network radio fell before the juggernaut of television, Boucher tried for months and perhaps years to establish a foothold in the new medium comparable to what he’d enjoyed in the middle and late Forties when he made hundreds of dollars a week (huge money in those days) providing plot synopses for Manny to expand into Queen radio scripts.

He got nowhere, but his frustration led to a memorable one-liner. “TV is to radio as radio is to films as films are to theater as theater is to publishing as publishing is to rational behavior.â€

Boucher once remarked that readers either love Gladys Mitchell or can’t stand her. I haven’t read enough of her dozens of novels to identify myself with either camp, but recently I tackled her second, The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop (1930).

Perhaps a better title would have been one Harry Stephen Keeler used a few years later, The Riddle of the Traveling Skull (1934), since much of the plot concerns a dead man’s sconce that keeps disappearing and reappearing in different places.

Mitchell’s sleuth, the spectacularly ugly Mrs. Lestrange Bradley, is a professional psychoanalyst who, like her forerunner Philo Vance, eschews physical clues and favors those stemming from the psychology of the murderer.

For some unaccountable reason the excellent sketch of the crime scene isn’t printed until page 305, so that no reader could know it was there when it might have been helpful. At the center of events is an old Druid sacrificial altar surrounded by a perfect circle of tall pine trees. “There it crouched, a loathsome toad-like thing, larger than ever in the semi-darkness.â€

Add Mitchell to the toad-haters of the world! I wonder why Mrs. Bradley, who’s often described as looking like a crocodile or a pterodactyl, is never compared to that sweet-singing and useful amphibian known to biology as bufo bufo.

Sun 12 Dec 2010

THE BLACK DAKOTAS. Columbia Pictures, 1954. Gary Merrill, Wanda Hendrix, John Bromfield, Noah Beery Jr., Howard Wendel, Robert Simon, Richard Webb, Peter Whitney, Jay Silverheels. Story & co-screenwriter: Ray Buffum. Director: Ray Nazarro.

One of the uncredited players of this rather short but compact technicolor western was Clayton Moore, marking The Black Dakotas one of the few movie team-ups between Moore and Jay Silverheels – other than as the Lone Ranger and Tonto, of course. (I didn’t include Moore in the credits above for one big reason: I never spotted him.)

History being one of my poorer subjects in high school, I don’t know how valid the premise of this movie is, but it’s one I don’t remember reading about or seeing in a western movie before. During the War Between the States, the opening narrative reads, the South sent men to the west to provoke uprisings by the Indians, forcing the North to send troops there – and away from the war – to protect the settlers.

Brock Marsh, who impersonates Zachary Paige in this movie as an emissary sent directly to the Dakota Territory, as played by Gary Merrill, is really the bad guy (through and through), and he definitely deserves the top billing.

Wanda Hendryx plays the fiery daughter of a Southern sympathizer who is hanged early on, while John Bromfield, the owner of the local stage line and the man who loves her, sides with the North, as do most of the local townspeople, excluding Noah Beery, Jr., who’s Merrill’s local contact.

All of the above is made clear within the first five minutes of the movie. (I always do my best not to reveal more than you’d want to know.) The rest of the 65 minutes running time is filled with lots and lots of accusations, high-riding action, double crosses, a kidnapping, multiple deaths from gunfire, and at stake, a fortune in gold ready for the taking.

The movie’s relatively hard to find on DVD, but it exists – I copied my copy on VHS from TNT back in 1991 — and you can even download a video of it from Amazon. If you were to ask me, though, you shouldn’t spend a lot of money to do so. It’s a perfectly adequate western movie — and maybe even more than that, given Merrill’s better than average performance as a bad guy — but an hour later even that’s as forgettable as the rest of the film.

« Previous Page — Next Page »