February 2011

Monthly Archive

Wed 9 Feb 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS (Crime & Mystery Television)

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

It is hardly surprising, perhaps, that one of the main reasons why so little has been written about the TV crime and mystery genre is that while everyone knows what constitutes as crime drama, no one has been able to define quite what it is. As has often noted before, the general consensus is that the crime and mystery, at its core, is a puzzle.

Essentially, when not a Whodunit (identifying the criminal) it is a Whydunit (the reasons for the crime). While the puzzle factor does indeed lie at the heart of the genre, the shape and structure of the puzzle may adopt a myriad of forms.

Certain basic characteristics can be deduced from the presentations themselves. It is more often than not contemporary. It has an urban setting (the city). It involves a crime of some nature (murder and robbery being among the foremost).

But these, of course, are not the mandatory hallmarks of a TV Crime & Mystery. The Western, for instance, has lawmen and outlaws, gunfighters and hold-ups, but they are hardly crime and mystery. Although in keeping with the TV vein here, the 1870s investigations of gunfighter/private eye for-hire Shotgun Slade (syndicated, 1959-61) and the police procedurals of Denver police detective Whispering Smith (NBC, 1961) may well be the cause for some constructive argument. And not forgetting Richard Boone’s early forensics in NBC’s Hec Ramsey (1972-74).

It has been expressed before that realism rather than stylization, a sense of authenticity and not outright adventure are the keynotes. The settings, the look, the narrative, and the procedure are all intended to be realistic. Or at least plausible. Content may often appear to be ritualized and behaviour somewhat stereotyped, but the characters are (in the majority of cases, at least) individuals rather than archetypes.

In this view, the TV genre is at times variably flexible and tends to be audience-led. It often bows to contemporary flavours and fashions. Its richest moments, however, offer access to a world not normally afforded the ordinary citizen, the slightly sinister world of the dogged detective or the cynical street cop, the nocturnal prowling of the private eye or the ice-cold operation of a secret agent.

The spirit of the genre is that law and order must be maintained at all costs, or, from the flip side of the coin, outwitted, outsmarted, and even defeated.

It can take the form of the pursuit: quiet and observational (as in Maigret [BBC, 1960-63], Agatha Christie’s Poirot [ITV, 1989-93; 1995]) or physically fast and furious (The Sweeney [ITV, 1975-76; 1978], Starsky and Hutch [ABC, 1975-79]), or even the long-form (The Fugitive [ABC, 1963-67]). It can be a psychological chess game (Cracker [ITV, 1993-96]), a medical examination (Quincy ME [NBC, 1976-83]), or a forensic probe (CSI: Crime Scene Investigation [CBS, 2000-present]).

The setting can range from Miss Marple’s cozy English village of St. Mary Mead to the dangerous night-time streets of The Wire’s Baltimore. Then there’s the milieu, the occupational routine of the sleuth. Or the social and/or professional world they inhabit. The hospital/medical milieu (Diagnosis Murder [CBS, 1993-2001]). The clerical milieu (Father Dowling Mysteries [NBC, 1989; ABC, 1990-91]). Wealthy eccentrics (Burke’s Law [ABC, 1963-65]). Horse racing (The Racing Game [ITV, 1979-80]). Et cetera, et cetera…

Because it contains so many elements and facets related to crime, engaging the viewer from a variety of directions, the TV genre can not be defined precisely.

The basic story-telling characteristics are an extrapolation of the forms and formats of, in one-part, the literary genre, one-part the radio drama and one-part the cinema. The TV form (not unlike the literary form) can embrace almost any genre, and can pursue any narrative strand. It can be set in the past or in the present. It can select as its point of narrative focus the law enforcer, the criminal, or the innocent bystander. It can be a TV play, a TV film, a miniseries/limited serial, an episodic series, or a series of self-contained episodes or thematic episodes (the anthology).

The detective or sleuth character is usually the leading figure in the narrative. Leading the path that the viewer is obliged to take, they follow the pattern of the investigation. It is the sleuth’s particular application to the details of the crime that provides the dramatic interest or action (whether the gung-ho tactics of a Lt. Frank Ballinger of M Squad [NBC, 1957-60] or the careful scrutiny of a Hercule Poirot).

The sleuth may have an assistant (Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson) or a partner (Inspector Morse and Sergeant Lewis). Or may consist of the a team (Ironside [NBC, 1967-75]) or a specialised squad (the cold cases unit of Waking the Dead [BBC, 2000-present]).

The subgenre of the private detective provides, usually, the loner (Peter Gunn [NBC, 1958-60; ABC, 1960-61], Shoestring [BBC, 1979-80]). Among the subdivisions are the amateur sleuths (Hettie Bainbridge Investigates [BBC, 1996-98], Kate Loves a Mystery [NBC, 1979]) and the sleuth couple (The Thin Man [NBC, 1957-59], Hart to Hart [ABC, 1979-84], Wilde Alliance [ITV, 1978]).

They can belong to established organisations (The FBI, Scotland Yard, MI5, the CIA, the French Sûreté, Interpol) or carry out their assignments on behalf of made-up agencies (U.N.C.L.E., C.O.N.T.R.O.L., Nemesis, CI5).

The most popular, and the most associated with the TV genre, has been the police drama. Mainly the Police Detective (Columbo [NBC, 1971-77; ABC, 1989-93], Inspector Morse [ITV, 1987-2000]) but also the Police Officer (Dixon of Dock Green [BBC, 1955-76], Joe Forrester [NBC, 1975-76]).

Among the subdivisions here are the undercover cop (Wiseguy [CBS, 1987-90], Murphy’s Law [BBC, 2001-2007]), the internal affairs/investigations cop (Between the Lines [BBC, 1992-94]), as well as the mobile cop (Z Cars [BBC, 1962-78], Highway Patrol [syndicated, 1955-59], CHiPs [NBC, 1977-83]).

The Adventurer. Thrill seeker; often on the lookout for dangerous and exciting experiences. Perhaps a round-up of the expected suspects along these lines would include Roger Moore’s The Saint (ITV, 1962-69), Robert Beatty’s Bulldog Drummond (in “The Ludlow Affair” pilot [ITV, 1958] for Douglas Fairbanks Jr Presents), The Agatha Christie Hour (with “The Case of the Discontented Soldier” [ITV, 1982]), Raffles (ITV, 1977), Josephine Tey’s Brat Farrar (BBC/A&E, 1986), Modesty Blaise (pilot; ABC, 1982), The Lone Wolf (syndicated, 1954), Jason King (ITV, 1971-72), The Baron (ITV, 1966-67) and, since this type of programming seems to have the greatest appeal to casual TV viewers, the countless others that we could all name.

The Private Detective (or Private Eye) has had a long and popular run in the TV genre. In the traditional American sense (77 Sunset Strip [ABC, 1958-64] as team, The Rockford Files [NBC, 1974-80] as loner) as well as the more British tradition of the ‘consulting detective’ (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes [ITV, 1984-85], Agatha Christie’s Partners in Crime [ITV, 1983-84]), along with the occasional UK leanings toward the American style (Public Eye [ITV, 1965-75]).

The Hard-Boiled sleuth (Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer [syndicated, 1957-59]) comes into this category. Also the amateur sleuthings of The Snoop Sisters (NBC, 1973-74) and The Beiderbecke Affair (ITV, 1985), either by design (a sense of over-curiosity) or by accident.

Perhaps as a footnote to the private detective division is the insurance investigator (John Ireland in The Cheaters [ITV, 1962-63]) or investigator for the diamond industry (Broderick Crawford in King of Diamonds [syndicated, 1961]).

The Lawyer sleuth and the Legal Procedural offer stories combining both private investigation and courtroom drama (Perry Mason [CBS, 1957-66], Sam Benedict [NBC, 1962-63]), and in more recent times the format has been used for corporate as well as constitutional enquiry (L.A. Law [NBC, 1986-94], Judge John Deed [BBC, 2001-2007]).

Spies, government agents and espionage have been in the literary genre almost as long as the crime and mystery genre itself. However, for the most part, their activities on both the printed page and the small screen have been popular for as long as there has been established political enemies to fight – which means, the genre was popular for most of the last century and remains (with the threat of terrorism), unfortunately, popular today.

The television espionage genre has presented the spy (the Anglo-U.S. side, of course) as either a lone crusader (during the communist witch-hunt early 1950s; I Led Three Lives [syndicated, 1953-56]) or as part of a secret, highly organised corporation, an element that reached its peak of popularity (quite often as parody) during the 1960s (The Avengers [ITV, 1961-69], The Man from U.N.C.L.E. [NBC, 1964-68]).

Later, Callan (ITV, 1967; 1969-72) returned the genre to a more serious track, culminating in John le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy in 1979. The highly popular Spooks (BBC, 2002-present; in U.S. as MI-5), for instance, features a youthful team of operatives involved in anti-terrorist activities. And so it goes…

The Period Sleuth has been popular on UK television since the early 1970s. A winning combination of costume drama and detective fiction, the works of such authors as Christie, Conan Doyle, Dorothy L. Sayers, G.K. Chesterton, and others, have produced the sagas of Lord Peter Wimsey (BBC, 1972-75), Father Brown (ITV, 1974), Campion (BBC, 1989), the ITV Sherlock Homes series (with Jeremy Brett; 1984 to 1994), Agatha Christie’s Poirot (ITV, 1989-93; 1995) and The Mrs Bradley Mysteries (BBC, 1998-99). The fascinating Canadian series Murdoch Mysteries (Citytv, 2008-present) continues to fascinate.

Occasionally, there are observations on contemporary life from the distant viewpoint of ancient Rome and Medieval England (the Falco and Brother Cadfael stories, respectively). The most popular period, it seems, is the fairly recent past, roughly the late Victorian era of Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper to the ‘nostalgic’ decade of the 1960s with Crime Story (NBC, 1986-88) and Heartbeat (ITV, 1992-2010).

A small note on the future and/or fantasy as ‘setting’: Isaac Asimov’s Caves of Steel (BBC, 1964); The Outer Limits (ABC) episodes “The Invisibles” and “Controlled Experiment” (both from 1964); The X Files (Fox, 1993-2002); Star Cops (BBC, 1987).

The Scientific Sleuth has surfaced intermittently over the decades (The Hidden Truth [ITV, 1964], The Expert [BBC, 1968-69; 1971; 1976]) until 2000 when CSI blazed a trail that brought the work of forensics experts to the fore.

Weapons and ballistics experts have featured in past stories, and currently Dexter (Showtime, 2006-present) has amassed an unexpectedly popular following by portraying the work of a blood splatter specialist (alongside his alter ego as a serial killer). The criminal psychologist has also gained a following over the years, especially with the success of Cracker in 1993 (Profiler [NBC, 1996-2000], Wire in the Blood [ITV, 2002-2008]).

Needless to say, there is more to the TV Crime & Mystery than just the above basic descriptions. In time, I intend to discuss aspects of the TV Gaslight Era drama, the Underworld, the Psychological Thriller, and other related TV forms.

In Part Two of PRIME TIME SUSPECTS, I will trace early examples of the genre (from 1930s/1940s TV works by Christie, Edgar Wallace, G.K. Chesterton, Patrick Hamilton and Edgar Allan Poe, among others), leading up to the episodic series of the late 1940s (such as The Plainclothesman, 1949-54).

Note: The introduction to this series of columns on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here.

Wed 9 Feb 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY CURT J. EVANS:

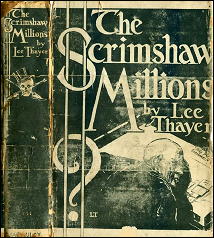

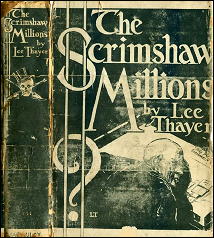

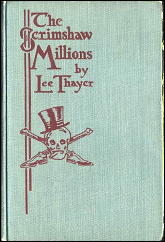

LEE THAYER – The Scrimshaw Millions. Sears & Co., hardcover, 1932. Hardcover reprint: The Macaulay Company, no date.

There are five killings in the tale, yet The Scrimshaw Millions is not remotely exciting. What should have been a gripping family extermination murder story on the order of S. S. Van Dine’s grandly baroque The Greene Murder Case (1928), instead is a snoozer the reader has to drive himself to finish.

But finish it I did, dear readers! It takes a lot to stop this fellah from plowing through to the end of a Golden Age whodunit, even a fourth- or fifth-tier one. Heck, I’ve read a dozen mysteries by Carolyn Wells!

In The Scrimshaw Millions someone is fatally poisoning the members of the Scrimshaw family one by one. A fortune is at stake — who will survive to inherit? And how long will it take for you to cease caring one iota?

To be fair, The Scrimshaw Millions struck me as superior to the books described earlier on this blog by Francis M. Nevins. The prose is serviceable, lacking those purple passages quoted by Nevins (at least until the cosmic retribution denouement Nevins has noted as a common feature of her books).

The characters, while sticks, are not irritating (except when meant to be — though perhaps we could have done without the Italian houseservant/blackmailer, regrettably named Guido). Generally speaking, you can believe this tale is taking place in the 1930s rather than a half-century earlier, unlike Carolyn Wells’ mysteries from the same decade.

Moreover, the clueing is respectable. And the murder means used in the five killings is…. Well, while it’s not original to Thayer (and John Rhode used it in a detective novel three years later, though only for a murder attempt late in the book), it’s kind of cute, in Golden Age Baroque fashion.

However, fatal weaknesses in The Scrimshaw Millions are its slack narrative, its sometimes careless writing and its lack of credible police procedure and scientific detail.

I have read the claim that the hugely prolific thriller writer Edgar Wallace, who boasted of being able to compose novels over weekends, in the course of one tale managed to change the name of his heroine (i.e., she starts off as Janet, say, and becomes Betty). Yet I had never come across such a phenomenon myself in an Edgar Wallace shocker, or, indeed, in a mystery tale by any other author — until I read Lee Thayer.

In The Scrimshaw Millions the secretary of that late, unlamented miser, Simon Scrimshaw, is introduced on page 51 as “Evangeline Osgood.” Yet five pages later her surname has changed to “Ogden.”

And there’s more! Although we are told for most of the tale that Simon’s two spinster sisters — thought at first to have died from heart failure–were both poisoned by “aconite” (I think “aconotine” was meant), late in the book the poison abruptly becomes arsenic.

All in all, I think it’s fair to say Lee Thayer was playing fast and loose with poisons, as well as with police procedure, in The Scrimshaw Millions. For no credible reason whatsover, three different poisons are used to slay in the tale, all by the same individual murderer: the alchemical aconite/aconotine/arsenic concoction, nicotine and cyanide (the last is later called hydrocyanic acid).

One might have thought this might have made the police suspicious of the character we are told works in a chemical factory, but, nope! It doesn’t seem to occur to anyone even to cock an eyebrow.

You might also think the murderer would have had to have been mad to adopt such an approach to attaining an inheritance. Well, hold on to your hats, it looks like he was:

“It’s too late now!” The exultant light of madness [shone in his eyes]. [p. 299]

Nearly forty years ago, Julian Symons labeled certain formerly quite popular and highly regarded detective novelists like John Rhode (a peudonym of Cecil John Charles Street) as “humdrums.” Other, more recent, mystery genre survey authors like P.D. James have followed suit, adopting Symons’ disparaging tone toward these writers.

Yet, compared to Lee Thayer, I say please, Lord, give me more “humdrums” like John Rhode. The use Rhode makes of science in his tales often is quite fascinating, ingenious, adroit and credible. In The Scrimshaw Millions none of those adjectives can be applied to Thayer’s (mis)use of science.

Traditionalist American mystery writers of the Golden Age of detection like Lee Thayer and Carolyn Wells often aped, as much they could, the form and milieu of detective novels of superior British counterparts.

Thayer, for example, clearly seems to have deliberately copied Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter/Bunter master-servant relationship with her own series detective, red-haired Peter Clancy, and his impeccable English manservant, Wiggar (the latter character was introduced by Thayer in 1929, ten years after she had debuted Clancy and six years after Sayers gave the world Lord Peter and Bunter). But Thayer and Wells are but pale shadows of far more substantial authors (and to be sure, there were many first-rate American traditionalists as well).

Still, the patented Lee Thayer cosmic retribution denouement so aptly described by Mike Nevins is impressive in its own loopy way. In The Scrimshaw Millions the entire house of the murdered miser falls in on the investigators and suspects just after the killer, pressed by the intrepid detective Peter Clancy, makes his mad confession:

The terrible cry of repudiation rang out in the desolate house, and as if the awful horror in it had terrible power there came a strange, wild shudder, a trembling through all the ancient walls, a hideous splitting crash, and the ceiling above their heads sagged downward, ripped across, and fell. [pp. 299-300]

Top that if you can, Agatha Christie and Hercule Poirot! Don’t tell me you’ve never wanted the roof to collapse on one of those drawing room lectures David Suchet gives in every darn one of his TV productions.

Providentially, one might say, only the mad murderer is killed when the house collapses in The Scrimshaw Millions. The nice boy lives to marry the nice girl, the policemen survive to continue getting murder cases all wrong, and Wiggar escapes the wreckage to continue happily serving his mildly concussed master Peter Clancy in many another perhaps-something-less-than-entirely-enthralling Lee Thayer mystery.

Tue 8 Feb 2011

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

At the name of Lee Thayer, most mystery fans draw a blank, but in other quarters it’s still well remembered. Emma Redington Lee was born in Troy, Pa. on April 5, 1874, studied at New York City’s Cooper Union and Pratt Institute, and got a job as an interior decorator (which in those days meant a painter of murals for the homes of the wealthy) at New York’s Associated Artists in 1890.

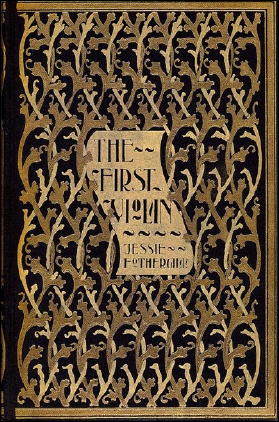

Some of her work was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 when she was still in her teens. Two years later she and Brooklyn architect Henry W. Thayer co-founded Decorative Designers, a firm which in the days before dust jackets produced binding designs, interior illustrations and the like for various New York book publishers. [An example of her work can be found at the end of this post.]

Lee and Thayer were married in 1909. The female partner is credited with having invented a method of using a split ink roller for printing color gradations on book bindings. Decorative Designs was first based in New York but migrated to Chatham, N.J. in 1921 and was dissolved, along with the partners’ marriage, eleven years later. Henry Thayer’s ex-wife called herself Lee Thayer for the rest of her life, probably because it was the byline on her detective novels.

Her first whodunit, The Mystery of the Thirteenth Floor, was published in 1919, when she was 45, and she continued turning out one or two books a year for well over four decades, a total of 61 titles.

All but one of them featured debonair red-thatched private sleuth Peter Clancy, who in Dead Man’s Shoes (1929) was joined by the intolerable imperturbable Wiggar, a Jeeves clone with an endless supply of scintillating bons mots like “Oh, Mr. Peter, sir!â€.

The union between master and valet lasted much longer than many marriages including Thayer’s own. She always thought of writing as a sort of sideline and kept her hand in as an artist by designing the dust jackets for all but the last three of her novels, several examples of which can be seen illustrating this column.

That she never became a household name is demonstrated by her only TV appearance. What’s My Line? was a popular CBS game show whose regular panelists (Arlene Francis, Dorothy Kilgallen and Bennett Cerf) were challenged to guess the occupations of various guests.

At the time of her appearance, May 11, 1958, she was 84 years old. Subsequently the program used her photograph in promotional ads: “This sweet little elderly lady writes blood-curdling murder mysteries!†Her last novel, Dusty Death, came out in 1966 when she was 92.

I know nothing about book design, but Thayer still seems to be highly regarded in that field. More than two dozen boxes of her Decorative Designs work are archived at UCLA, along with interviews taped very late in her life in which she reminisced about the firm’s work.

As a mystery writer she’s almost completely forgotten, and perhaps that’s the way it should be, because by ordinary standards there’s very little to recommend her. Feeble plots, clumsy writing, laughable characterizations, elephantine pace, zero fairness to the reader: you name the fault and Thayer’s books have it in spades.

Maybe it’s for this reason that I find in her what novelist and playwright Ira Levin told me he found in John Rhode: the perfect writer to take to bed. (Get that filthy thought out of your minds this instant!) But there are certain recurring elements in her novels that come close to qualifying her as an auteur.

One of these is the apocalyptic denouement. Whenever Peter Clancy has solved a murder to his own satisfaction but has no evidence that will stand up in court, God himself steps into the breach, striking the killer down from on high, while Thayer’s rhetoric swirls and squalls around and kicks up a furious storm.

In Accessory After the Fact (1943) it’s the founder of a quack religious cult who gets the treatment. The same furious deity strikes down totally secular villains in Out, Brief Candle! (1948) and Still No Answer (1958) and in who knows (I almost wrote God knows) how many Thayer novels I’ve never read.

Another Thayer hallmark is the off-the-wall crime method. Ransom Racket (1938) climaxes with Clancy’s reconstruction of a child-kidnapping: the gangsters drove a steam shovel up to the house, aligned the scoop with the baby’s upstairs bedroom window, stuffed the kid in the scoop and drove off undetected. (This is the book where Thayer writes “It was as dark as the inside of a cow†with a perfectly straight face.)

In Accident, Manslaughter or Murder? (1945) the victim is skating across a frozen lake on a moonless night, followed by the murderer in an iceboat which apparently makes no noise. Murderer maneuvers boat behind victim, swats him across the butt with an oar and propels him into a thin patch where the poor schmuck breaks through and drowns.

The novel I chose to concentrate on in my Thayer entry for 1001 Midnights was Out, Brief Candle!, which like Christie’s Death in the Air (1935) is about a murder on an airliner in flight.

It’s twice as long as it need have been, but the solution is passably clever, and I considered this the best Thayer I had read up to the time I wrote the entry. Later I discovered a copy of Evil Root (1949), which brings Clancy to a luxurious retirement home with stiff and unrefundable entrance fees and a suspiciously high death rate among recent residents. This was mystery writer/critic Jon L. Breen’s favorite Thayer, and after I’d read it I found I had to agree with him.

The Second Bullet (1934) has always had a special cachet for me because it’s set in the mountains of northern New Jersey, the state where I grew up. Thayer sets the scene as only she can: “[T]he strong autumn sun warmed the hollows with mists of purple and gold. The color of the woods sang like a great organ. The sky was that thrilling cobalt that seems as if it must be fragrant. Great clouds piled into the zenith. The air was warm and full-flavored like … claret properly unchilled.â€

An auto mishap brings Clancy and Wiggar to the remote mansion of a famous “psychic-analyst†where they discover that he seems to have shot himself to death shortly before their arrival. Concluding that the local cops are idiots who know nothing about detective work and speak in Texas cracker accents to boot (“Meet Captain Tom Joyce, inspector for this here countyâ€), Clancy decides to conceal crucial evidence, invite himself and Wiggar as house guests and stay on to investigate what he has quickly concluded is murder.

In due course he exposes yet another off-the-wall crime method. The murderer and an accomplice drove up to the victim’s isolated house in a utility truck with a long ladder. When the ladder was aligned with the victim’s second-story window, the killer climbed it and, like a demented Paladin, challenged the guy inside to a gun duel!

After twenty years as a northern Californian and resident of Berkeley, Thayer moved to the southern tip of the state and was living with relatives in Coronado in the fall of 1970 when she was interviewed by Jon Breen. At 96, Jon reported, she was still in relatively decent health and able to read with the aid of a combination lamp and magnifying glass.

She was extremely modest about her many mystery novels, saying only that “some are worse than others.†A year or so later there was an exhibition of some of her artwork at the UCLA library. She died on November 18, 1973, just a few months short of her 100th birthday.

The First Violin, by Jessie Fothergill, 1896. Cover design attributed to Lee Thayer.

Tue 8 Feb 2011

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

RAINES. NBC-TV, March 15 thru April 27 2007. Created by Graham Yost. Cast: Detective Michael Raines: Jeff Goldblum, Captain Lewis: Matt Craven, Carolyn : Nicole Sullivan, Lance: Linda Park, Boyer: Dov Davidoff. Recurring Characters: Dr. Kohl: Madeline Stowe, Charlie: Malik Yoba.

Raines is a rare example of a creative television series with a premise so different even the seasoned TV mystery fan will be pleasantly surprised.

Detective Michael Raines is a failed writer turned homicide detective who needs to talk out the crime with someone. When he loses his partner, and no one else will partner with him because they think he is a weird jerk, Raines turns to the dead victims.

Raines is not Topper meets Sherlock Holmes. The dead victims are not ghosts but figments of Raines’ own imagination. Because of this, the victims can not tell Raines anything he does not know. In “Fifth Step,” the victim’s head had been shot off by a shotgun blast. Raines sees the headless victim walking around until he sees a picture of her.

In each episode we watch how the victim changes as Raines learns more about the dead person. In the pilot, Raines imagines the dead girl as a young innocent woman. As he learns more that image changes. When he learns she may have had an affair with a married man, Raines’ image of her changes to resemble Kathleen Turner in Body Heat, complete with the film’s theme song playing on the soundtrack.

As Raines and the viewer learn more about the dead body the character of the victim becomes more developed. No longer is the victim just a body to start the mystery. He or she becomes more and more real to the viewer, so much so we mourn the loss and tragedy of the victim’s death.

Raines is eager to solve the case and get the victim out of his head. When he does solve the mystery, we have grown close enough to the victim to share Raines’ relief and sadness of closure.

The humor is dark, sarcastic, and at times can be laugh out loud funny. With the dead victim hovering around Raines waiting for answers, we feel the anger that fuels such humor. As a result the humor in this series has substance that is rare outside Raymond Chandler.

Jeff Goldblum is perfect as Raines, a man who lives with the terror he might be insane, yet driven to help find closure for the dead victims and those close to them.

Award winning showrunner Graham Yost (Justified, The Pacific) enjoys twisting the normal roles and rules of the mystery genre. In “Meet Juan Doe,” the police artist wants to do “graphic novels” and his sketch of a badly disfigured Mexican looks like Eric Erstrada.

Perhaps the best genre description of Raines is Victim Noir. Everything including the plot is centered around the victim. In “Stone Dead”, the plot begins as a story about a racist’s revenge against a judge, but as we learn more about the victim the crime changes. Often the backdrop of the crime challenges Raines’ perspective regarding social issues such as the homeless, addiction, and illegal immigration.

Raines is a series no TV mystery fan should miss.

All seven filmed episodes can be seen at Hulu.com.

Mon 7 Feb 2011

THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by MONTE HERRIDGE

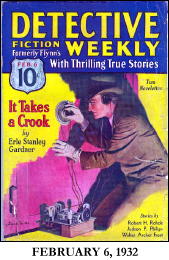

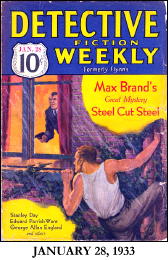

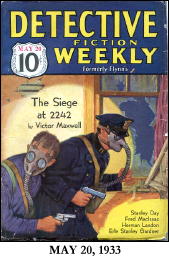

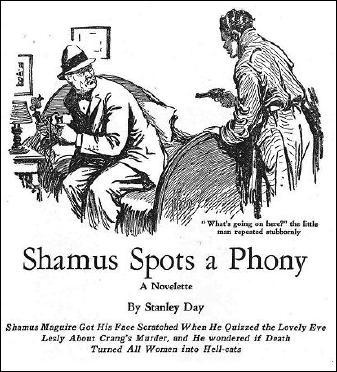

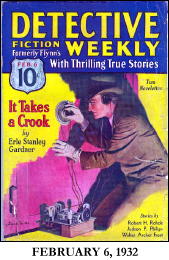

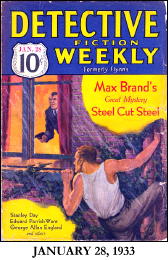

#1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

The “Shamus Maguire” stories by Stanley Day were a short series of eleven stories (some short stories and some novelette length) published in Detective Fiction Weekly from 1932 to 1934. There may be more.

The series involves the exploits of a hotel detective of indeterminate age, although he is noted as being a former policeman of 30 years service. Maguire retired on a pension four years before (according to his statement in the last story in the series) and became a hotel detective in the super-exclusive Hotel Paragon “to preserve himself from boredom.â€

His service time “had given him an air of authority that was no respecter of persons.†(The Glass Eye of the Corpse) He weighs 240 pounds (260 in some stories), a bit overweight, and smokes Little Policeman cigars. He lives in a house elsewhere, and doesn’t room in the hotel.

Hank Shaw is the assistant manager of the hotel, and gives orders to Maguire. He also likes to play jokes on Maguire, but in one case this backfired on him when a murder took place.

Maguire wasn’t concerned with the reputation of the hotel or whether the guests would flee if a scandal broke out. “He was concerned entirely with wrongdoing. And he possessed an unshakable belief that crime in the Hotel Paragon was his affair and his only.†(The Glass Eye of the Corpse)

When the city police got involved in the hotel on investigations, Maguire would interfere and if possible mislead them. Maguire’s “contention that he was capable of doing the hotel’s police work single-handed had a firm basis in fact.†(The Glass Eye of the Corpse)

Flynn and Schultz, two police detective-sergeants, also appear in the stories whenever a police investigation is called for. Maguire usually outsmarts them easily. Each story, it seems, is a ready-made conflict between Maguire and the police, and a kind of race to see who will solves the crime or crimes.

“Error in Time†is the first story in the series, and Shamus Maguire is actively involved in working on a case of kidnapping. One of the wealthy guests in the hotel has gone missing, and Maguire was assaulted by the kidnappers seeking his hotel keys. He recognizes one of the kidnappers, and sets out to track them down. His broken wristwatch provides the key clue.

“The Glass Eye of the Corpse,†the second story in the series, involves the murder of a guest in the hotel lobby. No one saw the murder, but the victim had recently told the assistant manager he thought he had seen a murder victim upstairs in one of the rooms. It takes a bit of work for Maguire to piece together what really happened and have the police arrest the guilty.

“Murder by the Window†is the third story. This involves a series of supposed suicides from the hotel windows by guests who have plenty of money. Maguire and the police are certain it is murder, but are not sure how the crimes were arranged. Maguire figures out the solution and puts it to the test with a fake guest and some money. As usual, Flynn and Schultz of the police are on hand for the investigation.

“Shamus Adds Them Up†is an interesting story. Thirty-seven pairs of pants have been stolen from occupants of the fifteenth floor of the hotel, and Shamus Maguire is puzzled as to the reasons. Money and valuables were left behind. Maguire suspects that the real reason may have something to do with the British lord and his relatives, and finally figures out the motive behind the crimes.

“Kindergarten Stuff†is a simple case for Shamus Maguire. A millionaire in the hotel seems to have been seriously injured by a fall. He is taken to the hospital where he later dies. His secretary seems to have been first on the scene with Maguire opening the hotel room door to discover the injured man. Maguire spends the rest of the story manipulating the secretary and the situation until he gets the secretary to sign a confession that he injured the millionaire. The title comes from Maguire’s statement to the secretary at the end: “It was simple as hell — kindergarten stuff for any cop.â€

“Dead Man’s Eyes†is another good entry in the series. Shamus Maguire investigates a supposed suicide by hanging in one of the hotel rooms, and decides it was really murder. He is generous enough to tell the police detectives his idea, which they take in another direction guaranteed not to solve the case. Meanwhile, Maguire figures out the reason for the murder and who the victim really is.

“Shamus Spots a Phony†is a better than usual entry in the Shamus Maguire series. This particular story is a good example of the kind of puzzling mysteries Maguire runs across, and it takes him a long time to figure out the solution. As usual in this series, he has to solve the crime despite the interference of two of the local police detectives.

“Other People’s Business†is a story that keeps Maguire on his toes, trying to get the better of a well-known professional criminal named Harry the Boss. An expensive oil painting is at stake here. It is on exhibition in the hotel, and Flynn and Schultz as usual are on the scene. When the painting is stolen, Maguire enjoys the discomfiture of the two policemen. However, Maguire figures out where the painting is hidden and prevents the criminals from escaping the hotel with it.

“A Doctor in the House†involves a kidnapping and a murder, as well as various goings on that seem to mystify the two police detectives. Shamus Maguire soon gets a handle on the entire affair and very quickly the crooks are behind bars.

“Social Error” involves a jewel theft and a murder which seems like it could be a suicide. The jewel theft is of the least valuable piece of jewelry in the ball-room full of rich people at the Hotel Paragon. Shamus Maguire solves the problem and makes the two detectives look especially foolish.

“Cold Blood†is the last story in the series, and is of novelette length. Maguire becomes an involuntary witness to a murder in the hotel, and sets out to discover the real story behind it. Maguire sees certain discrepancies in the murder scene, and this sets him off on his investigation. He is assisted in this case by an insurance investigator named Culver, who winds up saving Maguire’s life during the investigation. A better story than some of the others in the series.

This is an above average series, with very good stories. There is an element of humor in the stories, with Shamus Maguire and his interactions with the two police detective-sergeants. There were many series in DFW of similar attraction to the Shamus Maguire series, and these series gave the magazine its distinctive personality.

The Shamus Maguire series by Stanley Day:

Error in Time February 6, 1932

The Glass Eye of the Corpse March 12, 1932

Murder by the Window December 24, 1932

Shamus Adds Them Up January 28, 1933

Kindergarten Stuff February 18, 1933

Dead Man’s Eyes April 15, 1933

Shamus Spots a Phony May 20, 1933

Other People’s Business September 2, 1933

A Doctor in the House December 30, 1933

“Social Error” January 20, 1934

Cold Blood October 6, 1934

Sun 6 Feb 2011

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

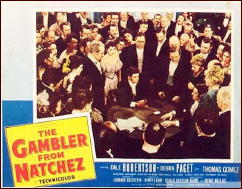

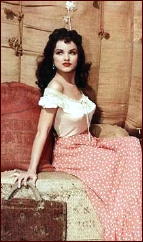

THE GAMBLER FROM NATCHEZ. 20th Century Fox, 1954. Dale Robertson, Debra Paget, Thomas Gomez, Kevin McCarthy, Lisa Douglas, Douglas Dick, Jay Novello, Woody Strode, John Wengraf, Donald Randolph, Henry Leontal, Parley Baer, Peter Mamakos. Screenplay by Gerald Drayson Adams & Irving Wallace, based on a story by the former. Director: Henry Levin.

A Southern swashbuckler rather than a Western, this entertaining outing is a canny variation on The Count of Monte Cristo.

Robertson is Captain Vance Colby, of the Louisiana Volunteers, returning in the early 1840’s to New Orleans after four years serving under Sam Houston in Texas. The son of a well known gambler, he returns to encounter social prejudice from dilettante Andre Rivage (Kevin McCarthy) after aiding Rivage’s beautiful sister Yvette (Lisa Douglas) with her carriage.

As Colby rides to meet his father after leaving his cold reception at Rivage’s plantation Araby, he is wounded when ambushed by Rivage’s man Etienne (Peter Mamakos), but escapes to the river where he is rescued by Melanie Barbee (Debra Paget) and her riverboat captain father (Thomas Gomez) whom he met earlier, and their man Josh (Woody Strode).

Recovering from his wound he returns to New Orleans to find his father murdered by Rivage, accused of cheating, with three witnesses; Claud St. Germaine (Douglas Dick), the weak fiancee of Yvette; Nicholas Cadiz (John Wengraf), the owner of the casino the Saint Cyr where his father was killed; and Jay Novello, the waiter serving that night.

With the police (in the person of the Commissioner played by Henry Leontal) on the side of the city’s Creole elite and the wealthy Cadiz, Colby must discover why his father was set up and murdered and avenge himself on the three men who committed the crime after having lost their new riverboat to Colby’s father in a game of 21, but in such a way the police can’t touch him.

The day he came home from Texas Colby pocketed a playing card, the three of spades, now he has written the names of his father’s murders on it and sets out to destroy them one by one.

The film is handsomely shot, with fine sets and costumes, and Robertson makes a dashing hero — even doing his own blade work in the final sword fight with McCarthy and handling it quite well.

The theme of the three of spades runs throughout the film, with the neat touch that in the final confrontation with McCarthy in a game of 21, it is the three of spades that puts McCarthy over 21 and loses the game for him, taking both the riverboat, and Araby, his family estate.

A well handled plot well written by Adams and Wallace, capable direction, and a handsome cast all combine to insure this one delivers everything it promises and more. Robertson is steadfast and dashing, Paget gorgeous, Gomez up to his usual scene stealing, and McCarthy a fine villain, by turns arrogant, snide, scheming, cowardly, and ruthless.

There are no surprises here, save perhaps for how well it all plays, and how good this little film really is. Dumas himself would have been proud to have inspired it.

Sun 6 Feb 2011

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

SHELDON SIEGEL – Judgment Day. MacAdam/Cage, hardcover, June 2008; trade paperback: June 2010.

Genre: Legal thriller. Leading characters: Mike Daley & Rosie Fernandez; 6th in series. Setting: San Francisco/Bay Area.

First Sentence: The oldest man on death row is eying me from his wheelchair.

Attorney Mike Daley, in spite of a promise to his ex-wife and law partner Rosie Fernandez, takes on a death-row appeals case. Former powerhouse-attorney Nate Fineman, is due to die in eight days. He was convicted of killing three men in a Chinatown restaurant shooting, but he claims he is innocent and the gun was planted by the police.

Now Mike has not only to prove Nate’s innocence, but to find and identify the killer in order to prevent Nate’s execution. There is one slight conflict; Mike’s late father was one of the officers at the scene of the shooting.

Living in the Bay Area, I do love books set here and it is delightful to read of places I know or have been and people whose names are iconic with the area. But it is also nice that Siegel gets the geographic and atmosphere right as well.

Siegal has a great voice, writes realistic dialoque and uses humor well, but it’s his characters I particularly like. His people are … people; not over-the-top or infallible. Mike and his ex-wife Rosie work together, are occasionally intimate but can’t life together yet they make it work so they are both involved in their children’s lives.

The contrast between Mike and his ex-cop brother, Pete, is a study in contrasts and adds dimension to both characters. The story is very well plotted.

The element of time counting down is always effective and, although I don’t know how realistic they may be, I do particularly like the courtroom scenes. [An attorney friend tells me the courtroom scenes are very well done.]

Siegel is a writer whose books I very much enjoy and was pleased to learn there is a new book on its way.

Rating: Very Good.

The Mike Daley & Rosie Fernandez series —

1. Special Circumstances (2000)

2. Incriminating Evidence (2001)

3. Criminal Intent (2002)

4. Final Verdict (2003)

5. The Confession (2004)

6. Judgment Day (2008)

7. Perfect Alibi (2009)

Sun 6 Feb 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

ELAINE VIETS – Killer Cuts. Obsidian, paperback original, May 2009.

Viets, returning to her “Dead-End Job” series after what was apparently a successful recovery from a stroke, has her protagonist Helen Hawthorne working in a high-end hair salon, with a marriage to her boyfriend, Phil, finally in the planning stages.

When Helen’s boss becomes a prime suspect in a murder case, the business at the salon bottoms out overnight, and Helen’s job and her marriage are both threatened.

Helen’s still living in an apartment at the Coronado Tropic Apartments, with an engaging, eccentric landlady, and still wondering if her ex-husband will once again turn up to threaten her precariously grounded existence.

Of course, the reader can be certain that the murder plot will be resolved, but that Helen’s long-term problems will linger into the succeeding novels in the series. And, as long as Viets’ light touch is as secure as it still in this eighth entry, that should be just fine with her faithful readers.

Editorial Comments: For a list of the novels in all three mystery series that Elaine has written, along with covers with most, follow this link to the Fantastic Fiction website. The three series: “St. Louis journalist-sleuth Francesca Vierling,” “Dead End Jobs,” and “Josie Marcus, Mystery Shopper.”

An interview that Pamela James did with Elaine Viets appears on the main Mystery*File website. It was conducted in December, 2004, which was quite a few books ago, but it’s not entirely out of date and (in my opinion) still interesting.

Sat 5 Feb 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

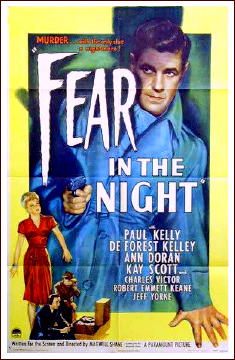

FEAR IN THE NIGHT. Paramount Pictures, 1947. Paul Kelly, DeForest Kelley, Ann Doran, Kay Scott, Charles Victor, Robert Emmett Keane. Screenplay: Maxwell Shane, based on the short story “Nightmare” by William Irish (Cornell Woolrich). Director: Maxwell Shane.

A nicely-done ”B” with some good atmospherics buoying up so-so characterizations and an indifferent script, wrapped around a fine, dream-like plot.

DeForest, haunted by nightmares that he’s killed someone in a make-believe room, confides in his Cop Brother-in-Law Paul, then finds that the room really exists and the murder actually occurred.

With a little sharper writing, this could’ve been a much better film, but as it is, it just misses the mark. DeForest is written as a trepidant weakling, and Paul as a Tough Cop, and the two of them never manage to break out of the cardboard confines of their cliche’d characters (he alliterated.)

Worse, writer/director Maxwell Shane seems perfectly content not to develop DeForest’s character, as if he never realized the Dramatic Potential in the story of a man trying to convince the World and himself that he’s not a Killer.

Well, it’s at least noir-ish enough to keep it interesting.

Editorial Comment: The movie in its entirety can be watched online here. (Follow the link.)

Sat 5 Feb 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

KINGSLEY AMIS – The Crime of the Century. Mysterious Press, US, hardcover, 1989; reprint paperback, October 1990. UK edition: J. M. Dent, trade paperback, 1989.

In London, three women are found stabbed to death within a few days, each with a similar “clue” planted on the Body. So the Police have a Serial Killer on their hands, and to quiet growing unrest, the Under-Secretary, with the wisdom of his breed, forms a Committee to deal with the problem.

But as the murders continue, it becomes obvious to one of the Committee-Men that the Killer must be one of his fellow-members.

Crime of the Century was originally a serial in the Sunday London Times in 1975, and like most serials it’s passably entertaining but ponderously lightweight. Amis fills the Committee (read Suspect list) with every modem “type” he or I could imagine, and rings in some rather banal Red Herrings, such as the Terrorist Group extorting money and the Nice Guy who suffers Mysterious Blackouts.

After the Fifth Installment in the Times, readers were invited to submit their own endings, and the winner is reprinted here, along with Amis’ own finish. I hate to say it, but the Winner’s solution was a bit better.

« Previous Page — Next Page »