March 2011

Monthly Archive

Thu 10 Mar 2011

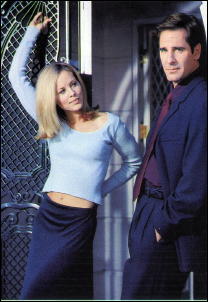

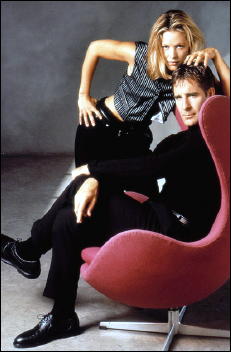

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

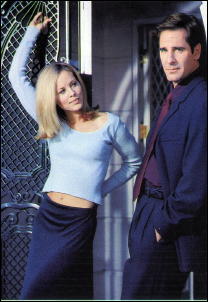

MR. & MRS. SMITH. CBS. September 20, 1996 through November 8, 1996. Cast: Mr. Smith: Scott Bakula, Mrs. Smith: Maria Bello, Mr. Big: Roy Dotrice, Rox: Aida Turturro (two episodes). Created by Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar.

Mr. & Mrs. Smith was a better than average mindless TV romantic comedy mystery.

Mr. and Mrs. Smith worked for The Factory, a worldwide private intelligence firm with the latest gadgets and unlimited resources. The company was run by a man known as Mr. Big. The Factory had a rule that no agent could know anything about another agent’s past. So, while off saving the world and solving crimes, the Smiths spent their free time trying to uncover the other’s secret past. Why they don’t even know the other’s name!

If this secret past bit sounds like Remington Steele doubled, it was not by accident. Creators Lenhart and Sakmar were on the writing staff of Remington Steele during the third and fourth seasons. Michael Gleason, co-creator and showrunner of Remington Steele, wrote the final episode of Mr. & Mrs. Smith.

The series had an interesting twist to the overdone “will they or won’t they” cliche. At times, she was willing to hop into bed with him, and he was tempted, but there was something in his past stopping him.

Mr. and Mrs. Smith were complete opposites, and on TV that makes them the perfect team. She was talkative and impulsive while he was quiet and deliberate. If one did not know something, the other was an expert on the subject.

The sexual attraction each had for the other was understandable. However, the two leads’ chemistry did not heat up the screen. Scott Bakula gave his usual performance, ranging from wooden to over the top. Maria Bello was a wonderful surprise, with an emotionally expressive face able to reveal Mrs. Smith’s damaged past without a word.

The writing was typical television, ranging from great fun to embarrassingly bad. The mysteries relied more on twists, but did feature an occasional obvious clue. The stories’ pace were fast enough, so if you turned off your brain, you did not care about the, at times, unbelievably stupid behavior of the characters.

The best clues were not for the mystery of the week, but for the arc story of the mystery of Mr. and Mrs. Smiths’ pasts. The characters and their relationship evolved each week as they learned more about each other.

Sadly, CBS aired only nine of the thirteen episodes, and at least two were noticeably out of order. In “The Grape Escape”, Mr. Smith goes through Mrs. Smith’s hidden trunk of past mementos. But it is a trunk the viewer and Mr. Smith did not know existed until “The Publishing Episode” that aired the week after.

Without the last four episodes, the viewers missed out on the satisfying ending to the central mystery of the characters’ pasts.

The final four episodes were aired sometime overseas. All thirteen episodes are available at You Tube. No DVD is currently legally available.

EPISODE INDEX

Pilot (9/20/96) Written: Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar. Directed: David S. Jackson. Mr. Smith meets the future Mrs. Smith while each, on opposite sides, attempt to find a missing scientist who had invented a new energy source.

The Suburban Episode (9/27/96) Written: Mitchell Burgess and Robin Green. Directed: Oz Scott. The Smiths move to the suburbs of St. Louis and pose as new neighbors to a man suspected of selling top-secret government codes.

The Second Episode (10/4/96) Written: Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar. Directed: Ralph Hemecker. Mr. and Mrs. Smith help a bumbling assistant stop his boss from selling arms to a terrorist.

The Poor Pitiful Put-Upon Singer Episode (10/11/96) Written: Del Shores. Directed: Nick Marck. The Smiths try to find out whom wants to kill the head of a small record label.

The Grape Escape (10/18/96) Written: Susan Cridland Wick. Directed: Daniel Attias. The Factory sends the Smiths on a mission to save the vineyards of Europe from a scientist’s bug bombs.

The Publishing Episode (10/25/96) Written: Douglas Steinberg. Directed: James Quinn. The Smiths have to stop the sale of a tell-all spy book written by a missing British spy named Steed. Each Smith wants to find the book first, so to read about the other’s past.

The Coma Episode (10/28/96) Written: Douglas Steinberg. Directed: Michael Zinberg. Mr. Smith plays doctor with Mrs. Smith taking the role as coma patient so they can get closed the a guarded coma victim that knows the plans of terrorists to attack a peace conference.

The Kidnapping Episode (11/1/96) Written: Mitchell Burgess and Robin Green. Directed: Sharron Miller. Before the Smiths can discover who is causing problems at a drug company, their client is kidnapped.

The Space Flight Episode (11/8/96) Written: Michael Cassutt. Directed: Lou Antonio. When an ex-astronaut hires The Factory to find a space prototype and his son, the trail leads the Smiths to Area 51.

The Big Easy Episode (never aired on CBS) Written: Del Shores. Directed: James Whitmore Jr. The Smiths visit New Orleans when The Factory is hired to clear a Senator’s mistress of a conviction for selling government secrets.

The Impossible Mission Episode (never aired on CBS) Teleplay: Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar. Story: Douglas Steinberg. Directed: Artie Mandelberg. The Smiths help fellow Factory agents, the Jones, trap some counterfeiters.

The Bob Episode (never aired on CBS) Written: Sanford Golden. Directed: Jonathan Sanger. Bob, a friend from Mr. Smith’s pre-spy days, gets caught in the middle between the Smiths and a terrorist with enough plutonium to make an atomic bomb.

The Sins of the Father (never aired on CBS) Written: Michael Gleason. Directed: Rob Thompson. Mr. Smith disappears while in mid-assignment when he is blackmailed with his past. While The Factory writes him off, Mrs. Smith rushes to his rescue, whether he wants her to or not.

Wed 9 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

HELEN REILLY – Death Demands an Audience. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1940. Hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1941. Paperback reprints: Popular Library #7, no date [1943]; Macfadden, 1967; Manor, 1974.

The paperback publisher [Macfadden] implies that this is a novel with some impossible or at least difficult crimes. “One victim was killed in a department store window. Another died before the startled eyes of a policeman on guard duty. The third breathed his last in a crowd of people coming out of a theater.”

The first victim was killed in a department-store-window display, all right, but the display was in the cellar at the time of the crime and was raised with corpse later. The next victim had locked the policeman in a basement, so the cop certainly didn’t see him die. The third death had nothing to do with a theater crowd or any other crowd.

Equally disappointing is the novel itself. The murderer is not only the least likely person but a most unlikely one. Inspector McKee traps the murderer by taking a picture as the fourth murder is attempted. He implies that he knew who it was all the time, but I don’t believe it. A fair mystery with a most unsatisfactory denouement.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.

Editorial Comments: A long profile of Helen Reilly’s work by Mike Grost can be found on the main Mystery*File website. (Follow the link.) Accompanying Mike’s article is a detailed bibliography I put together for her.

Previously reviewed (by me) on this blog:

The Canvas Dagger (1956) (very short)

The Silver Leopard (1946)

Wed 9 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Characters[6] Comments

As a followup the recent post that listed the Top Ten favorite mystery writers in 1941, it has belatedly occurred to me that there was a later similar poll taken, some 30 years later, one that already appears on this blog.

Repeating, if I may, the introduction of that previous post:

Back in the early 1970s, the country of Nicaragua asked Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (EQMM) “to set up a poll to establish the dozen greatest detectives of all time†in anticipation of that nation’s issuing a commemorative set of twelve postage stamps to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Interpol. This book [Masterpieces of Mystery: The Supersleuths, edited by Ellery Queen] is a result — or, perhaps, a by-product of that request.

“EQMM conducted three polls of mystery critics and editors, professional mystery writers, and mystery readers. It was from the last group that an unexpected (to Ellery Queen) result came:

“Only one fictional detective was voted for unanimously by mystery critics, mystery editors, and mystery writers — not surprisingly, Sherlock Holmes. But, surprisingly, the vote for Sherlock Holmes by mystery readers was not unanimous: no less than 64 readers out of 1,090 failed to rank Holmes as one of the 12 best and greatest. Surprising, indeed. (Surprising? Incredible!)â€

Here are the poll results, in order of popularity:

1-Sherlock Holmes

2-Hercule Poirot

3-Ellery Queen

4-Nero Wolfe

5-Perry Mason

6-Charlie Chan

7-Inspector Maigret

8-C. Auguste Dupin

9-Sam Spade

10-Father Brown

11-Lord Peter Wimsey

12-Philip Marlowe

13-Dr. Gideon Fell

14-Lew Archer

15-Albert Campion

16-George Gideon

17-Miss Jane Marple

18-Philo Vance

19-The Saint (Simon Templar)

20-Roderick Alleyn

21-Luis Mendoza

22-Sir Henry Merrivale

23-Mike Hammer

24-James Bond

25-Sergeant Cuff

26-Inspector Roger West

By my count and estimation, there are at least four who would not a make a dent in such a list if one were to be made today, and maybe even more than that.

Wed 9 Mar 2011

The Tale of Mr. Fergus Hume and Mr. William Freeman

or, The Reviewer’s Comeuppance

by Curt J. Evans

Despite having produced over 130 mystery novels between 1886 and 1932, the year of his death, the English born, New Zealand raised author Fergus Hume (1859-1932) is known — to the extent he is known at all today — for one work, his debut murder tale, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab.

Accounts typically claim that over 500,000 copies of Hansom Cab were quickly placed into eager purchasers’ hands (some sources suggest up to as many as a million copies may have been sold), making the novel a landmark financial success within the mystery genre.

After relocating from New Zealand to Australia in the 1880s and finding employment as a barrister’s clerk, Fergus Hume soon manifested marked literary tendencies. He published a few stories and began writing plays, but the latter efforts went nowhere. Determining that what the public really desired was a murder tale, Hume pored over the celebrated mystery novels of the French author Emile Gaboriau (1832-1873). Then he produced his own crime story, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab.

Finding resistance among Australian publishers to this work as well, Hume was forced to the expedient of privately printing it. To everyone’s amazement the novel sold briskly. Hume then made the mistake of his life, for a pittance parting with the book’s copyright to an Australian publisher who soon had it flying off shelves not only in Australia but Great Britain and the United States. Apparently Hume never made a penny off the book again.

Undaunted by his ill turn of economic fortune, Hume determined to make his living as a novelist. By 1888 he had moved to England (where he would live the rest of his life) and had ditched his Australian publisher. The next year saw the publication of Hume’s first mystery novel set in England, The Piccadilly Puzzle.

A fascinating review of The Piccadilly Puzzle appeared in the inaugural issue of Zealandia, a short-lived New Zealand literary journal (it ran for twelve issues). The reviewer of Puzzle, William Freeman, was also the editor of Zealandia and a prominent New Zealand journalist of his day. His review of the tale is acute but also strikingly harsh in tone. However, if Hume was offended by this review, he soon enough had the last laugh on Freeman.

Before I get to the Zealandia review and the bizarre fate of the reviewer, however, some words about The Piccadilly Puzzle are necessary.

Clearly inspired by the recent Jack the Ripper murders (as was another Victorian mystery novel published at this time, Benjamin Farjeon’s Devlin the Barber), The Piccadilly Puzzle revolves around the mysterious murder of a woman on a foggy night in a major London thoroughfare.

The woman, initially thought to be a “streetwalker” (shades of the Whitechapel murders) soon is identified as a certain Miss Sarschine, the mistress of a prominent lord who, it seems, has just eloped to the Azores on his private yacht with another lord’s wife. The dead woman was not strangled or stabbed but, rather, poisoned — the poison apparently being one of those convenient tropical toxins utterly unknown to Western science, the use of which later would be much frowned upon in the Golden Age of the detective novel (roughly 1920 to 1939).

Perhaps not coincidentally, poor defunct Miss Sarschine, that lovely lady of easy virtue, had a pair of Malay kris, complete with fatally poisoned blades, hanging on a wall of her love nest (apparently deadly poisoned kris on the wall add just that right final touch to a romantic evening).

The London police put a private detective named Dowker entirely in charge of the case (something which struck me as rather odd). As a character this Mr. Dowker is not interesting at all, but, worse yet, he has a “colorful” Cockney sidekick, a street urchin named Flip, who speaks like this:

“ ’e gives me sumat to eat when I arsks it, so I goes h’up to cadge some wictuals, I gits cold meat, my h’eye, prime, an’ bread an’ beer, so when I ’ad copped the grub, I was a-gittin’ away h’out of the bar when a swell cove comes in — lor’ what a swell — fur coat an’ shiny ’at. Ses to the gal, ses ’e….”

As much as I admire Hume’s perseverance in typing so many apostrophe marks, I have to confess my eye flew past Flip’s speeches as fast as was possible. I have to wonder whether Hume was inspired to create Flip by Arthur Conan Doyle’s ragamuffin assistants to Sherlock Holmes, the Baker Street Irregulars, who had appeared in the premier Holmes tale, A Study in Scarlet (1887). I cannot recall the Irregulars speaking quite so irregularly as our friend Flip, but perhaps my memory is playing me false.

The mystery in The Piccadilly Puzzle is certainly as convoluted as Flip’s speech (in addition to untraceable poisons, Hume for good measure also throws twins — another Golden Age no-no — into the mix as an additional plot complication); but, alas, it is not really fair play, an overheard confession being necessary to accomplish the killer’s exposure.

Hume became known for having a consistent narrative construction in many of his mystery tales, whereby a series of individuals are suspected in turn, only to have Hume pull a “surprise” culprit out of his top hat.

This keeps the story rolling along, but makes the wary reader immediately look for the culprit among the characters whom no one suspects. It’s the least likely suspect gambit famously associated with Agatha Christie, but Hume lacks the Golden Age Crime Queen’s uncanny finesse.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about The Piccadilly Puzzle is the sexual immorality (or amorality) of the characters, which is portrayed with striking casualness by the author.

One would conclude from this tale that the English aristocracy in 1889 was hopelessly debauched. One lord seduces a young woman, sets her up in a London love nest, then commences an affair with a woman married to another lord (in an exceedingly odd twist, this woman turns out to be the identical twin sister of his aforementioned mistress).

Additionally, we learn that the straying wife had already had a sexual affair with another, younger man, before breaking with this man to marry the lord (she was ambitious for a title). After learning of his wife’s wayward ways the lord she married regrets that he impulsively wed the hussy rather than simply make her his mistress, as the other lord did with the other sister.

“Sounds like the second act of a French play,” remarks one character. Indeed!

It is perhaps worth noting that Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray was published a year after The Piccadilly Puzzle. Wilde’s famous short novel incurred some considerable criticism that year as “nauseous,” “unclean,” “effeminate” and “contaminating.”

While Fergus Hume clearly had not attempted a work of literary ambition in The Piccadilly Puzzle, he nevertheless in the tale gave readers a whiff (whether fragrant or foul depending on the individual) of fin de siecle decadence.

Which brings us, finally, to William Freeman’s hostile piece on The Piccadilly Puzzle in the pages of Zealandia. Rarely have I encountered such a scathingly detailed review of a mystery novel. In Freeman’s eyes, the work was a failure on all counts, literary, technical and moral.

At the time Freeman wrote his condemnatory review of Hume’s fifth mystery tale, Hume was a New Zealand national celebrity, author of, as Freeman put it, “the most successful novel of the day.”

To be sure, Hume soon would be overtaken and surpassed by Arthur Conan Doyle (who had already published A Study in Scarlet in 1887 and would produce, in an explosion of creative genius, The Sign of Four and the dozen short stories comprising The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in 1890-1892).

Yet by producing mystery tales at an awesome rate — he was, along with the later Edgar Wallace and John Street, one of the most prolific producers in the history of the mystery genre — Hume managed to maintain a relatively successful writing career over the next quarter century or so.

Only after the outbreak of World War One, when he lost his American publisher, G. W. Dillingham, and the onset of the Golden Age, when his health declined and his books came to seem increasingly antiquated, did Hume find his financial prospects darkening. His last years were spent in a single rented room in a bungalow and he died in near poverty, only a couple years after his onetime rival Conan Doyle.

Yet those dark days were a long way off in 1889, when Hume was still big news and interest in his literary fate was high, especially in New Zealand, where he was the colonial who had astonished the writing world (even if he had not always impressed it: “What a swindle The Mystery of a Hansom Cab is,” wrote Arthur Conan Doyle bluntly in a letter at this time. “One of the weakest tales I have read, and simply sold by puffing.”).

Like Conan Doyle, William Freeman, a noted controversialist in his day, was not one to be intimidated by fame. Freeman himself had authored in 1889 a sensation tale (modeled on Charles Dickens) entitled, with unwitting prescience on his part, He Who Digged a Pit.

In the very opening lines of of his review of The Piccadilly Puzzle, Freeman made his poor opinion of Hume’s latest crime novel brutally plain. The book, he wrote damningly–

“…is not a tale: it is a bald bare plot, with nothing good and pleasing to recommend it. It has absolutely none of the touches of poetic descriptive, pathos and humor which explain the popularity of [Hume’s] earlier books. There is not a fine sentiment in it from cover to cover; no tender chords are stirred by a single passage; there is no delicate shading, no touch of an artists’ hand; nothing new–no anything but a sombre, highly sensational plot, and an unadorned description of an impossible detective’s unavailing efforts to unravel the tangled clues of a crime, the original of which is clearly one of the Whitechapel murders.”

In addition to finding The Piccadilly Puzzle poorly written — its prose lacked the “beauties which hid the repulsiveness of the plots in [two of Hume’s earlier tales, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab and Madame Midas]” — Freeman damned the book as well for essentially failing to adhere to what some thirty years later, in the Golden Age of the detective novel, would be called the fair play standard.

In Freeman’s eyes Fergus Hume did not play fair with his readers but, rather, with out-of-bounds mendacity led them down the garden path:

“The most remarkable feature about the characters is that very nearly all of them (the hero included) scatter about a reckless profusion of lies, introduced not at all because they are necessary but solely to mystify the reader. The author leads the way himself in this deception, for at the very outset he deliberately misleads the reader as to the thoughts of the murderer (pp. 5 and 7) and throws suspicion on the hero by making him start at hearing mentioned the name of the street in which the murder is committed (p. 6), though at the time he had no idea that any murder had been perpetrated and there was no reason he should attach more importance to a mention of Jermyn Street than any other street in the city. It is permissible in fiction to so relate actions as to infer [sic] that an innocent man is guilty, but surely both the above artifices are unjustifiable.”

Freeman also takes Hume to task at length for the numerous improbabilities the author scattered throughout his tale, ending by asserting, “to solely construct a whole plot out of nothing else [but improbabilities] is straining the credulity of readers too far.”

Having disposed of Fergus Hume’s writing and plotting to his own evident satisfaction, Freeman then proceeded to blast The Piccadilly Puzzle for sundry moral transgressions. This line of argument was to prove ironic in the face of Freeman’s own subsequent behavior.

“The worst feature of the book,” thundered Freeman righteously, “is its moral tone.” In Freeman’s horrified eyes, the characters of The Piccadilly Puzzle wallowed “in a seething mass of moral corruption which the author cynically disdains to hide behind the slightest shadow of the veil of decency.”

Indeed, Hume seemed “to consider it natural that everybody should be immoral.” He portrayed this immorality “with a coarse fidelity” that Freman found “positively repulsive.”

Freeman closed his resoundingly minatory review article by expressing his “emphatic condemnation” of other New Zealand writers embarking on such a “dangerous” literary course as Fergus Hume had. Hume now represented New Zealand before the eyes of the world, Freeman noted. Sadly, he had shirked his duty as an author to stand with that “which is clean, wholesome and pure-minded.”

I personally would love to know what Fergus Hume made of Freeman’s review of The Piccadilly Puzzle.

Or of the sudden and surprising downward turn in Freeman’s own personal fortunes:

Zealandia soon went defunct and in 1890 Freeman (whose full name was William Freeman Kitchen) had become the editor of the Dunedin Globe. A year later he resigned from the paper, amid great controversy. (The paper under his management made what were later determined by government investigation to be baseless charges against the Seacliff Lunatic Asylum, its offices were subjected to arson and Freeman was found to have lied about the amount of money the paper was losing each month.)

By 1893 Freeman had moved to Australia, where it was announced in a newspaper that he had died, leaving behind his wife and two children in New Zealand. Yet that same year Freeman was discovered in the flesh, very much alive and in the company of a female correspondent. He had, it seems, falsely announced his own death. He was arrested and tried for desertion and bigamy. Ultimately he committed suicide in 1897, at the age of 34.

Truly, a turn of events almost (if not quite) as odd as those in The Piccadilly Puzzle! As far as I know, however, no twins and no tropical poisons unknown to science were involved in the real life William Freeman Kitchen mystery.

Fergus Hume would go on for about another three decades to write an unbroken string of nearly one hundred more mystery tales–though his name tenuously survives in genre history only as the author of The Mystery of a Hansom Cab. While Hume’s The Picadilly Puzzle may be justly forgotten, William Freeman’s review of the novel deserves to be remembered.

Tue 8 Mar 2011

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

TELL NO TALES. MGM, 1939. Melvyn Douglas, Louise Platt, Douglass Dumbrille, Gene Lockhart, Zeffie Tilbury, Sara Haden, Florence George. Screenplay: Lionel Houser. Director: Leslie Fenton.

Terrific two-fisted programmer from MGM that moves like an express and has a surprising amount of heart as well as brains. Douglas is Michael Cassidy, the editor of the Evening Standard, a big city newspaper about to be shut down by publisher Matt Cooper (Douglass Dumbrille) in favor of the tabloid rag he uses as his mouthpiece.

When Cassidy stumbles on the story of the century, a hundred dollar bill that was part of a kidnap ransom shows up in his hands, he plans for the Standard to go out in a blaze of glory. Setting out to follow the trail of the wandering hundred dollar bill, he enlists the help of the only witness to the kidnapping, a feisty school teacher sick of being kept virtual prisoner by the police (Louise Platt).

Cassidy follows the trail of the bill from a mousy jeweler about to be married; to a society doctor and his cheating wife; to a the wake of a black boxer possibly killed for his involvement with the kidnappers; to an attractive singer at a police benefit (with half the cops in town looking for him), a surprising source; and finally a casino owned by Gene Lockhart who leads him to the kidnappers, but for deadly reasons of his own.

At each turn the screenplay is better than it needs to be, and the individual stories well drawn and handsomely shot, from the grieving widow of the boxer (the Alley Kid); to the frightened look on the doctor’s wife’s face when cornered about her lie; to a nicely sinister bit by Lockhart as the casino owner. Zeffie Tilbury is particularly good as a tough old lady copy editor who has been with the paper fifty years and known Cassidy since he was a copy boy.

The finale is a bang up escape from the two kidnappers by Douglas and Platt, and a nicely rounded up ending, that, if a bit more upbeat and happy than the rest of the film would suggest, still leaves you more than well satisfied.

I first heard about this from William Everson’s The Detective Film, and it is every bit as good as promised: a mix of tough guy dialogue, two fisted journalism, solid detective work, and sentiment that is just the right combination of schmaltz and cynicism that might have come out of Black Mask or Dime Detective, and the kind of stories about two-fisted reporters that Nebel, Sale, Babcock, and Coxe specialized in.

Next time this shows up on TCM, be sure and catch it. It’s as slick as any A-film, and packs as much in sixty nine minutes as most A-films did in films half again as long.

Tremendous pace, sharp crackling dialogue, affecting vignettes by great character actors, and a pretty good mystery that unfolds on the run, this one can hold its own against many a bigger picture that doesn’t have half its heart or head.

Tue 8 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Authors[34] Comments

As posted today on Elizabeth Foxwell’s The Bunburyist blog:

The Top Ten favorite mystery writers of 1941, as reported by the New York Times on April 18, 1941, based on a survey conducted by Columbia University:

1. Dorothy L. Sayers

2. Agatha Christie

3. Arthur Conan Doyle

4. Ngaio Marsh

5. Erle Stanley Gardner

6. Rex Stout

7. Ellery Queen

8. Margery Allingham

9. Dashiell Hammett

10. Georges Simenon

Follow the link above for more information, including who was considered “Best Detective.”

Any surprises? Based on recent discussion on this blog, any comments?

Tue 8 Mar 2011

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

MAIGRET. Granada TV, UK. Second series: six 60-min episodes. 14 March through 18 April 1993. Michael Gambon (Chief Inspector Jules Maigret), Geoffrey Hutchings (Sgt. Lucas), Jack Galloway (Inspector Janvier), James Larkin (Inspector LaPointe).

— Reprinted from

Caddish Thoughts #42, May 1993.

A second six part series of Maigret has recently been and gone. I watched with extra vigilance after the adverse comments about the first series in Mystery & Detective Monthly. I enjoyed this series. It’s steady and reliable without being flashy or exciting and adapts the stories well into a 50-minute format.

The difficulty of adapting stories from a long series of books to screen is to achieve a uniformity of time and character. The decision to shoot exterior scenes in Budapest, since it was easier to recreate 1950’s (the time period chosen for the series) Paris there rather than in the Paris of 1993 seemed reasonable, although exterior scenes were kept to a minimum anyway.

I do not subscribe to the theory that English actors speaking English portraying Frenchman speaking French should adopt the accent of a Frenchman speaking English badly (as, say, Poirot — although, of course, he’s Belgian). The producers, correctly in my opinion, used the appropriate English accent to portray the rank or position of the speaker, so a doctor would speak with a polished accent where a labourer would adopt a rougher less educated one. A foreign sounding accent was only used for characters who were not French and could be assumed to be speaking French with a foreign accent.

I thought an article in the current issue of Armchair Detective rather silly. It seems we should have had a French actor playing the part, although it isn’t made it clear if the actor should be speaking in French or English.

If English, I suppose we’d be looking for a French actor who speaks English but not well. If they ever make a series of Lindsey Davis’s books I wonder how they’re going to cast Falco? Perhaps they’ll be able to dig up an ancient Roman from somewhere.

The author of the article also says: “If we wanted an Englishman playing the part, we’d watch a repeat of the dreadful American TV movie starring Richard Harris.”

I’m quite at a loss as how to evaluate this statement. Apart from the fact that Harris is not English anyway, is he saying that once an actor has portrayed a character, even if badly, he would watch it repeatedly rather that watch an actor from the same country play the same role?

Anyway for the record the six stories were: “Maigret And The Night Club Bouncer,” “Maigret And The Hotel Majestic,” “Maigret On The Defensive,” “Maigret’s Boyhood Friend,” “Maigret And The Minister,” and “Maigret And The Maid.”

Mon 7 Mar 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

HOME AT SEVEN. British Lion Film Corp., 1952. Released in the US as Murder on Monday, 1953. Ralph Richardson, Margaret Leighton, Jack Hawkins, Campbell Singer, Michael Shepley, Margaret Withers. Based on a play by R.C. Sherriff. Director: Ralph Richardson.

[Before reading the review that follows, you may wish to go back to Dan’s earlier comments on

Interrupted Journey, reviewed

here. —Steve.]

That scene toward the end of Interrupted Journey came strongly to mind as I watched another British Film, Home at Seven, the only film ever directed by Sir Ralph Richardson, and a pleasant surprise from start to finish.

When Great Actors turn to Directing Fillums, they often get a bit mannered. Sometimes unbearably so. I’m reminded of Laurence Harvey’s awful The Ceremony and John Wayne’s ponderous The Alamo. Even films I rather enjoy, such as Olivier’s Hamlet and Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks suffer from a certain amount of self-conscious narcissism.

Which is why I was so charmed by Home at Seven’s unpretentious spontaneity. From start to finish, it’s a quiet, workmanlike job of entertainment never flashy — boasting fine performances from Richardson (always a delight to watch) Margaret Leighton and Jack Hawkins.

I can tell a little about the plot this time: Richardson plays a Bank Clerk who returns home from work one night — carrying the evening paper; promptly at Seven as usual — to find his wife in tears. His first impulse is to soothe her, of course, and when she tells him he’s been missing for the last 24 hours, he poohpoohs the notion, pointing out that he’s clean, shaved, his clothes not slept in, and carrying the Monday Paper: Hardly the appearance of a man who’s lost a day.

Surely, he tells her, it must have been a dream she had while napping. Must stop working so hard, and all that. At which point he discovers that it’s Tuesday’s Paper he’s holding.

It’s an intriguing notion to start a film with, and it gets better as Richardson discovers that money he was responsible for is missing and a close associate is dead. Very swiftly, the film becomes another paranoid nightmare, on the order of Interrupted Journey, but done with just a touch more realism and consideration to character.

Unlike the characters in most thrillers, everyone in Home at Seven seems perfectly real and very likable: Richardson’s Average-Guy Hero, his fretful wife, Jack Hawkins’ sympathetic Doctor and even someone named Campbell Singer as an apologetic but insistent Police Inspector. One gets a real sense of ordinary people who’ve had some awful intrusion into their lives and can’t figure how to cope with it.

There is a stunningly effective scene in Home at Seven where Richardson and his wife are at home and he thinks the Police are coming to arrest him for Murder. Sound familiar? I thought so too. But wait; Feeling the Long Arm of The Law at his back, Richardson sits down with his wife at the kitchen table and quietly begins to explain to her how to do the Accounts.

It’s a moment all the more touching for its restraint with both of them trying hard not to cry as they deal with the commonplace aspects of a nightmare, and it shows a sensitivity and intelligence that are just too rare in the Film Thriller.

Sun 6 Mar 2011

THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

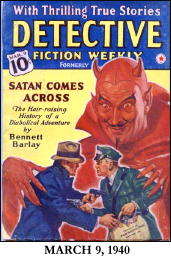

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by MONTE HERRIDGE

#2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

The Happy McGonigle stories by Paul Allenby was a short series of at least eight stories published in Detective Fiction Weekly from 1940 through 1941. The stories are about the misadventures of petty criminal Happy McGonigle and his partner in crime, Blackie Roberts.

The stories are narrated in first person by Blackie Roberts, who tries to explain the problems of trying to plan and commit crimes with a person like Happy McGonigle. In the first story Roberts explains very briefly what McGonigle is like:

“He is not a gent who is looking for trouble all the time. Oh, no! Happy is the simplest, dumbest boob that ever turned a dishonest penny. From the top of his mop-like blond hair to his 13-D feet, he is plain uncut, yokel.†(“A Cockeyed Wiggley”)

Roberts notes that he has trained Happy over a ten year period, and that Happy is handy with burglar tools and in fights, but often makes him sorry he knows him. Blackie explains that he is the brains of the duo, and Happy is the brawn. Trying to plan crimes with help like Happy is difficult. He has to be careful to explain the crime plans very carefully to Happy, who is often not paying close attention.

Happy is happiest when he is involved with his latest hobby. He has been through many hobbies, and in the first story in the series, “A Cockeyed Wiggley,†his hobby is collecting matchbook covers. This hobby causes problems with their crime plan for this story, but somehow everything turns out all right, though they don’t make any money from their crime.

The next story, “Red, White and Very Blue,†finds the two criminals on their way back from gambling on horse racing at Pimlico, stopping off in Washington, D.C. for some rest and relaxation. Happy turns into a typical tourist, going to see all the sites and spending a lot of money on fancy clothes.

They run into trouble when they encounter a group of spies. The spies con the two out of all of their money, and also con them into stealing airplane plans from a house. Fortunately for them, they realize what is going on and hand the plans back to the U.S. Government, and wind up making themselves look like heroes in the process.

As shown in the story, Black Roberts can be just about as gullible and naïve as Happy McGonigle. So Blackie’s comments about his partner need to be taken with a grain or two of salt.

In the story “In the Bag,†the two are planning a jewel robbery, but another of Happy’s hobbies interferes with the plans. Happy has started taking dancing lessons in order to be an “adagio†dancer.

Blackie thinks this is ridiculous and tries to get Happy to work with him on the robbery. But Happy has promised to deliver a suitcase for the dance teacher. The title refers to the fact that three new identical leather suitcases become involved in the plot and the guys try to keep straight which contains what.

When the newspaper reports that the dance studio staff has been arrested for drug smuggling, the bag situation gets more complicated.

In “Gone With the McGonigle,†Happy’s newest hobby is to become a writer. So he buys a lot of paper, a filing cabinet, a portable table, and a typewriter. After spending all of this money he thinks he is ready to become a writer.

However, he finds being a writer is not all it is cracked up to be. Happy finally goes on a destructive rampage through his editor’s house, which he and Blackie are burglarizing.

In “McGonigle the Great,†Happy is struck with the wish to be a professional magician. He learns a number of magic tricks while he and Blackie are staying at a large hotel. Unfortunately, he makes so many mistakes that people laugh at his act.

Even though the audiences enjoy the mistakes, Happy does not like being laughed at. Blackie notes that Happy is somewhat deficient in a sense of humor. While all of this is going on, Blackie Roberts and a newspaper reporter (who is teaching Happy magic tricks) are searching the hotel for an absconding bank teller who has stolen a hundred thousand dollars. The magic act plus the search make for a situation that is sure to get out of hand quickly.

“McGonigle Makes a Bid†finds the duo trying to take a vacation and behave in a law-abiding manner. They head off to the wilds in a car, but wind up stranded at a large house occupied by a crazy man. Unknown to them, the grounds are also the hiding place of three criminals who don’t like the interruption of Happy and Blackie.

In “Bombs Tick Once Too Oftenâ€, Happy and Blackie are visiting the World’s Fair and trying to enjoy themselves. However, Happy thinks that someone is trying to plant a bomb at the Fair. Their first move is to follow two suspicious acting characters (who are carrying a suitcase) around the Fair. Later, when Happy discovers a bag that is ticking and whirring, he is positive he has found a bomb. Altogether, a very stressful day for Blackie and Happy.

“The Skeleton of Danny Force†is atypical of the other stories in the series. Happy McGonigle does not play the primary focus of the story. Blackie Roberts is more the focus of this story, as he and Happy go out to a rural town to help one of Happy’s friends in his dealings with the local Scrooge-like banker. A skeleton is dug up by a local, and this provides the means by which Blackie can counter the banker and get the better of him.

The final story, “In Union There Is McGonigle,†The two guys get into union activity, primarily because they think they can make some money in it. Definitely not in it for the benefit of the workers of pretzel salters industry, which is their working area.

As usual, they run into numerous complications in the process, and only Blackie’s planning gets them out of the situation and with a profit for a change. Also as usual, it was Happy’s doing that they got into union activity in the first place. He doesn’t appear to ever think through the consequences of his actions.

As you no doubt can tell from the above story descriptions, this series is meant to be a light comedy series of stories. No seriousness invades the stories, and the cast bumbles their way along the story lines without any serious damage or landing in jail.

The series is not really that funny, however, though it aims to be. It is okay as a mildly humorous look at two bumbling criminals.

There were other humorous series in DFW in the past, including two (Fluffy McGoff , 1931-37, and Murray Magimple, 1935-37) by Milo Ray Phelps, who died in 1937. Not having read much of the various humorous series, I can’t say which ones are the best or succeed at being funny.

The Happy McGonigle series by Paul Allenby:

A Cockeyed Wiggley March 9, 1940

Red, White and Very Blue March 30, 1940

* Grand Marshal McGonigle June 1, 1940

In the Bag June 15, 1940

Gone With the McGonigle June 29, 1940

McGonigle the Great August 3, 1940

McGonigle Makes a Bid August 17, 1940

Bombs Tick Once Too Often October 19, 1940

* Insurance for Sale November 23, 1940

The Skeleton of Danny Force January 18, 1941

In Union There Is McGonigle April 26, 1941

* It’s All in the Angle May 31, 1941

(*) These three were added after the list was first posted. Thanks to Phil Stephensen-Payne for pointing them out as likely possibilities in the comments, and for Walker Martin for confirming that they are indeed McGonigle stories.

Previously on this blog: #1. Shamus Maguire by Stanley Day.

Sun 6 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Authors1 Comment

Several days ago I posted a notice of author Lou Cameron’s death last October. As it turns out, this was in error. I received an email from his daughter this morning saying that while his health is not the best, he is definitely still with us.

The Louis J. Cameron who died had the same date of birth as given in Contemporary Authors for Lou Cameron the author. This suggests that either CA is in error, which is a good possibility, or that what happened was just another of life’s many mysterious coincidences.

I apologized to his daughter for the mistake and asked her to accept the page and the comments that were left as a tribute to her father, which I’m happy to say that she has. To that end, I will rework the page into a brief biography to go along with the previous cover gallery of many of the books he wrote, but this time without a mention of his non-existent passing.

« Previous Page — Next Page »