August 2011

Monthly Archive

Sun 14 Aug 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[14] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

FREDRIC BROWN – Night of the Jabberwock. E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1950. Paperback editions include: Bantam #990, April 1952; Morrow-Quill, 1984. British edition: T. V. Boardman, hc, 1951.

Based on two pulp stories: “The Gibbering Night†(Detective Tales, July 1944) and “The Jabberwock Murders†(Thrilling Mystery, Summer 1944).

I recently took a couple days to re-read the greatest book ever written in the English Language, Fredric Brown’s Night of the Jabberwock, which can’t be beat in terms of structure, action, characterization, or much of anything else for that matter.

The tale is of a night in the life of “Doc” Stoeger, middle-aged editor of a small-town weekly newspaper — the kind of publication now put out by a syndicate if it exists at all, in a town that nowadays has become a suburb or a fiefdom of Wal-Mart.

But back in 1950, the small town and its paper were vibrant, charming bits of Americana, just like Brown’s novel, which starts off with Doc putting his sleepy little paper to bed, sadly looking at the front-page news of a church rummage sale and wishing he could somehow just once break a major story.

What follows is a night of wonderland-style adventures and reverses, as a mysterious visitor initiates him into The Vorpal Blades, a select club devoted to serious study of Lewis Carroll, major stories fly into his lap like scattered playing cards, he becomes a small-town hero, a hunted fugitive, kidnap victim and kidnapper himself.

All this is tossed off with the deceptively easy style only Fredric Brown could do so well. And speaking of Tossed Off, someone should go through this book with a calculator and see how much Doc drinks during the course of an evening; every chapter is punctuated by him having two or three drinks, then sobering up, then drinking again, drinking more, sobering… at some point it gets a bit ridiculous, but somehow the humor only adds to the charm of this witty and elegant adventure through a looking-glass.

By the way, this sent me back to re-reading Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, books I hadn’t seen since childhood. And I have to say their charm was sadly lost on me.

There’s some excellent doggerel there, perhaps up to the level of Edward Lear, but in their hurry to get from one scene to another, the stories never seem to get anyplace; colorful characters never do anything interesting, and conversations all consist merely of people contradicting Alice.

Or am I missing something?

Sat 13 Aug 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE SMILING GHOST. Warner Brothers, 1941. Wayne Morris, Brenda Marshall, Alexis Smith, Alan Hale, Lee Patrick, David Bruce, Helen Westley, Willie Best. Screenplay by Kenneth Garnet and Stuart Palmer, based on a story by Stuart Palmer. Director: Lewis Seiler.

I saw this spooky comic mystery on its initial release, when I was still in short pants, and for years the image of the Ghost, glowing eerily in the dark, haunted my dreams. A recent screening by Turner didn’t, perhaps, chill me in the way the original release did, but it’s still an engaging Old House mystery, with the requisite dose of sliding panels and screams in the night.

When out-of-work Alexander “Lucky” Dowling (Wayne Morris), besieged by debt collectors, is hired to play the role of the fiancé of heiress Elinor Bentley (Alexis Smith) for a month, he accepts the job without realizing previous suitors have been severely injured in a suspicious car crash and poisoned by the bite of a venomous snake.

Accompanied by his valet Clarence (Willie Best), Lucky moves into the Bentley house (it’s a bit too small to be called a mansion) where very quickly an attempt is made on his life and he realizes the job is a potentially lethal one.

Lucky is slower on the uptake than Clarence but he quickly buys into the fiction that Elinor truly loves him, a fiction that is eventually dispelled by the more clear-headed perspective of reporter Lil Barstow (Brenda Marshall), but not before his devotion is put to the ultimate test, which could be either marriage to the predatory Elinor or murder at the hands of the Ghost.

The household is crowded with members of the Bentley clan, headed by matriarch Helen Westley, with Charles Hulton giving an indelible portrait of a professor whose hobby is not only collecting shrunken heads but actually producing them in his laboratory. Alan Hale bumbles around as a general factotum and security detail, and Lee Patrick sizes up the situation with her usual wry humor.

Willie Best, in these supposedly enlightened times, gives probably the most controversial performance, with the most offensive (and, dare I say it, funniest) moment taking place when he conceals himself in a coal bin in the basement.

This is probably not quite in the league of Paramount’s Old House classics, The Cat and the Canary and The Ghost Breakers, but it kept breaking me up and occasionally produced a hint of the chills that captivated me at a long-ago Saturday matinee. And noting the name of a noted concoctor of comic mysteries as a co-author of the script, I suspect that he’s responsible for the more delightful comic notes in the screenplay.

Sat 13 Aug 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

HILARY BURLEIGH – Murder at Maison Manche. Hurst & Blackett Ltd., UK, hardcover; date not stated but known to be 1948.

Another one-shot detective novel from an all-but-unknown author today, but not a book, in my opinion, that’s nearly as successful as David Burnham’s Last Act in Bermuda [reviewed here ]. To begin with, to set the scene, so to speak, let me quote from early on in the affair, from page 13:

The salon at Pierre Manche’s was never crowded. His clientèle was too carefully chosen for that. One could say with truth that it was chosen, for in these days the distinction of being dressed by Mache is so eagerly sought that it is more often the case of Manche choosing whom he would dress than of Manche seeking clients. To have admission to his dress parades was a distinction. Tickets took the form of invitations to an exclusive function, and men and women came as guests to that beautiful room, where they were personally welcomed by the little fat man at the head of the stairs and regaled with cocktails or sherry of undoubted vintage, as a prelude to the display of fashion.

So all right, then. Both of the ingredients for a successful Golden Age Mystery are present, as touched upon in my comments on the Burnham book. Essential ingredient number one: A house (or even better, a manor) full of glitzy people, or an exclusive business establishment of some sort, or some other meeting place of the rich and famous.

Essential setting ingredient number two: When Gleba, Mache’s most beautiful mannequin (model) is found murdered immediately after a showing of a wedding dress (page 18) there has been only limited access to the salon and the dressing rooms behind. Only the people on the premises can be presumed to have been the killer.

One difference between this book and the Burnham’s is how early on the victim’s death occurs. Here it seems almost too soon, only eighteen pages in, and there has been no time to know anything about the girl, except that she wears clothes well. Thus there has been no time for the reader to react properly and have any feeling about such minor matters such as rationale, reason and motive.

In Murder at Maison Manche, matters like these are left to be revealed only gradually, but the major one (as far as I will reveal it to you) is that the wedding dress Gleba had been wearing just before she was killed was that of a woman in the audience with whose fiancé she (Gleba) recently had had an affair.

The detective from Scotland Yard who is quickly called to scene is Chief Inspector Tellit. He is described in detail on page 74 as a thick-set man dressed in well-cut and utterly uninspired clothes, ugly hands, far from good-looking but with an often kindly look in his deep blue eyes. In general, however, “he was considered a hard man†as far as crime and criminals are concerned.

This is far from his first brush with a mysterious death, you may also be interested in knowing, since on page 48, his assistant, Det. Sgt. Fry feels “content that he was once again with Tellit on a murder case.â€

Tellit is a man for keeping track of details, gathering together scraps of information and putting them together like pieces of a jigsaw, as we are told on page 101. Every so often the author (in the guise of Inspector Tellit) feels the need for a recap and a provisional summing up, a device that seems worn-out today, but it is one which this reader, at least, almost always finds welcome.

If this is not as gripping a detective yarn as David Burnham’s one was, it is for two reasons, the first being the huge amount of coincidence that is involved to put all of the actors on the scene at precisely the right moment, with the right means (a mysterious snake venom manufactured only in one lab in South America), the right motive and the right opportunity.

Secondly the pacing is oddly off. In particular, the book also seems to “end†at page 180, with 27 more pages to go, and another character, previously relegated to the background is needed to emerge to set up the “real†solution. One more coincidence, and usually for a suspension of disbelief, all that an author is usually allowed is one, or no more than two.

The right ingredients are present, in other words, but they get themselves muddled up a bit at the hands of an author whom I will call an amateur – without knowing anything else about her – in the finest sense of the word.

Sat 13 Aug 2011

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

KATE ROSS – Cut to the Quick. Viking, hardcover, 1993. Penguin, paperback, 1994.

Genre: Historical mystery. Leading character: Julian Kestrel (1st in series). Setting: England/Regency era, 1824.

First Sentence: Mark Craddock paced slowly, deliberately, back and forth behind the desk in his study.

After Regency dandy and detective Julian Kestral rescues young Hugh Fontclair from embarrassment at a gambling hall, he is, in turn, asked to serve as best man for Hugh’s forced marriage to Maud Craddock.

Kestral, along with his man Dipper, travels to the Fontclair country home for a weekend with both families. The last thing he expected was to find the body of an unknown murdered woman in his bed or having to provide Dipper innocent of the act.

For those of us who love period mysteries, Ross is one of the best. She captures the period with exquisite detail from dress, manners, speech. Her characters are wonderfully drawn portraying all levels of society.

Kestrel is the character at center stage. He is the personification of the Regency dandy, exhibiting droll cynicism and detachment. Upon meeting Hugh’s young sisters, he comments: “I rather like making friends with women before they’re old enough to be dangerous.”

However, under the veneer is a consideration for others, an admiration for goodness, awareness of people’s natures and a determination for justice. Although there are quite a number of characters in the story, each is so well drawn as never become confused.

The plot is very strong. It’s not a locked-room mystery as the key is on the hall table. It is very much a case of who is the victim, how did she get there and what was her relationship to the people in the house. It’s a step-by-step investigation with plenty of twists and turns along the way. Best of all, I certainly did not predict the killer.

While sadly, Kate Ross only published four books before her death in 1998, this, as are all of her books, is very well worth reading, and reading again.

Rating: Very Good Plus.

The Julian Kestrel series —

Cut to the Quick (1993)

A Broken Vessel (1994)

Whom the Gods Love (1995)

The Devil in Music (1997)

Fri 12 Aug 2011

DRAMATIC SCHOOL. MGM, 1938. Luise Rainer, Paulette Goddard, Alan Marshal, Lana Turner, Genevieve Tobin, John Hubbard, Henry Stephenson, Gale Sondergaard, Erik Rhodes, Virginia Grey, Ann Rutherford, Hans Conried. Director: Robert B. Sinclair.

A lengthy as the credits list is above, the cast is in fact much larger than this. If this makes sense, and I hope it does, Dramatic School is an A-production with B-picture sensibilities, with lots of young players in the cast whose names were not yet known at the time. A big budget movie, relatively speaking, in other words, without a lot of pretense or hype.

And I thoroughly enjoyed it. One reason is the presence of Luise Rainer in this film, even though it was shown on TCM last week during all-day salute to the second-in-command, Paulette Goddard. Luise Rainer had a short but sweet career in Hollywood, but with two Oscar wins in only two tries, there can’t be many other actors or actresses who can beat that.

The two Oscar winners? The Great Ziegfeld (1936) and The Good Earth (1937). After making Dramatic School, Luise Rainer appeared in one movie in 1943, then nothing till 1949 and the TV era. Why? Run-ins with studio bosses, marrying, and not much caring about life and a career in Hollywood.

She’s a joy to watch in Dramatic School, however, as she plays an aspiring star of the French theatre in truly romantic fashion: her eyes to the sky and not always watching where her feet are leading her.

By night, a worker in a assembly plant making gas meters (I believe), by day a young student in a Parisian dramatic school, where the fanciful tales she tells about herself are the subject of doubt and at times near-derision by the other students.

Even one of her teachers (Gale Sondergaard) has taken a dislike to her, in spite of her talent. An obvious case of jealousy — one of several cases of cliché-like moments in Dramatic School, but like this one, they’re always skirted but never quite fallen into. (Well, most of them.)

Sometimes dreams do come true, and once in a while they (miraculously) do come true for Mme. Louise Mauban. And (as twists in the plot begin to unfold) when they don’t, when she takes a tumble, well, watch and see. Unless you’re deeply cynical about stories like this one – and to tell you the truth, I can see why – you will be as enchanted as I.

Fri 12 Aug 2011

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

JACK IAMS – A Shot of Murder. William Morrow, hardcover, 1950. Dell #722, paperback, 1953.

When a young American woman, Nita Romaine — a night club singer — disappears in Eastern Europe, recently married reporter “Rocky” Rockwell of the Riverside, Ohio Record manages to talk his editor into sending him and his bride to Europe in order to look for her — the missing woman’s fiancé being a local man.

It isn’t long before Rocky realizes that someone doesn’t want him to be successful. A man mistaken for him is thrown over the side of the ocean liner transporting them, and efforts are made in Paris to get him entangled with the French police.

Rocky is helped in Paris by Mrs. Pickett, the paper’s society columnist but is forced to go to Poland alone (though an attractive French woman with reasons of her own for going to Poland attaches herself to him) and continue his search.

From reading the dust jacket, I gather that this was the third book in a series in which Mrs. Pickett was the lead character. Mrs. Pickett is something of a Rosalind Russell type. In this book, however, Rocky is definitely the major character.

If I were to compare this with another series I would say it was entertaining in the same way that Manning Coles’ Tommy Hambledon novels are entertaining. Lightweight fluff, that is, a pleasant read, but about as realistic as a three dollar bill.

One wonders how big a city Riverside, Ohio, is and how a local paper can afford to pay to send a reporter and his wife gallivanting through Europe.

— Reprinted from The Hound of Dr. Johnson #9, March 1992.

Bibliography: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin]

JACK IAMS, 1910-1990.

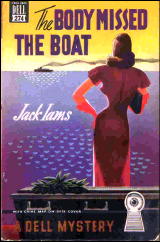

The Body Missed the Boat (n.) Morrow 1947.

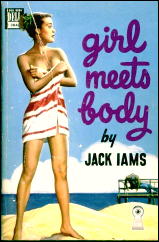

Girl Meets Body (n.) Morrow 1947.

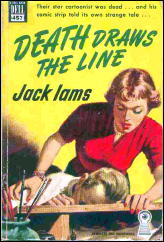

Death Draws the Line (n.) Morrow 1949.

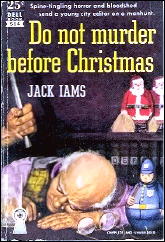

Do Not Murder Before Christmas (n.) Morrow 1949 [Rocky Rockwell; Amelia Pickett]

What Rhymes with Murder? (n.) Morrow 1950 [Rocky Rockwell; Amelia Pickett]

A Shot of Murder (n.) Morrow 1950 [Rocky Rockwell]

Into Thin Air (n.) Morrow 1952.

A Corpse of the Old School (n.) Gollancz 1955 [Amelia Pickett]

Editorial Comments: Al seems to have missed Amelia Pickett as a character in A Shot of Murder. Perhaps her role was small, but I’ll still send him a note to make sure he knows. It’s interesting to see that Iams’ last book, another Amelia Pickett novel, was never published here in the US.

Thu 11 Aug 2011

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

TIMOTHY HALLINAN – The Man with No Time. Simeon Grist #5. Morrow, hardcover, 1993. Avon, paperback, May 1995.

I have enjoyed previous tales of over-educated LA private detective Simeon Grist considerably. I enjoyed this one much less. Much less.

Grist finds himself in the middle of the LA Asian gang scene, as the twin children if his Asian ladylove are kidnapped; seemingly by an old friend of the family from mainland China, who aided them in escaping from there many years ago.

It quickly becomes apparent that the old “friend” is being pursued by an LA ganglord, and Grist is quickly up to his neck in gangsters of various Asian persuasions, all suitably villainous.

This isn’t a poorly written book. It also isn’t a private detective book. It’s a well-done kick-ass type fairy tale of the Parker/Crais variety, though Hallinan isn’t quite in their league as prose stylist. Grist is assisted by a black semi-legal, and six black brothers who are his friends, and by a youthful Vietnamese gang member who he has co-opted; all entertaining characters.

The storytelling is fine. It’s a bloody action-packed heroes-against-bad-guys tale with in-depth characterization not a major concern. But it isn’t the book I wanted to read, nor one I expected him to write. I’d have bought an “Executioner” if I wanted to read one.

Pfui. Color me disappointed.

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #8, July 1993.

The Simeon Grist series —

1. The Four Last Things (1989)

2. Everything but the Squeal (1990)

3. Skin Deep (1991)

4. Incinerator (1992)

5. The Man with No Time (1993)

6. The Bone Polisher (1995)

The Poke Rafferty series —

1. A Nail Through the Heart (2007)

2. The Fourth Watcher (2008)

3. Breathing Water (2009)

4. The Queen of Patpong (2010)

Poke Rafferty is an ex-pat travel writer and sometime adventurer trying to settle down in Bangkok with his fiancee and their adopted daughter.

Thu 11 Aug 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

JUSTIN GUSTAINIS – Hard Spell. Angry Robot, US, paperback original, July 2011; UK, ppbk, June 2011.

Hard Spell, “an Occult Crimes Unit Investigation” novel, and the first in a projected series, is set in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Scranton, like the rest of the country, has been learning to deal with the “supernatural element” for some fifty years in the wake of the infiltration of returning World War II troops from Europe by various supernatural beings.

It’s not been an easy path and the dream of the day envisioned by Martin Luther King when “naturals and supernaturals” would live together in harmony is not yet realized.

Detective Stan Markowski is a member of the Scranton “Supe Squad,” housed in the basement of Police Headquarters, and works with his long-time partner, Paul di Napoli, on the night shift (and the implied pun is probably intended).

When di Napoli is killed by goblins in a negotiated situation that turns sour, he’s replaced by Karl Renfer, a “tall, gangly kid, all elbows and knees,” whose career came under a cloud after his former partner claimed he failed to come to his defense during a confrontation with a voodoo master raising corpses from the dead. Renfer was cleared by a Review Board, but Markowski is still wary of his younger, less experienced partner.

Both detectives are put to the test by a series of murders related to an ancient book of necromancy, the “Opus Mago,” that will give the possessor the power to awaken one of the Great Ones, powerful entities who predate man and, if they are resurrected, could have the power to supplant him.

Or, as the irreverent Renfer so colorfully puts it, the “Opus Mago” is a “recipe book for cooking up different kinds of Truly Bad Shit.”

This alternative history crossover nimbly maneuvers a narrow path through the minefield of the conflicting demands of the police procedural and the apocalyptic horror novel in a promising debut for the fledgling series.

Editorial Comments: A neat trailer for Hard Spell can be found here on YouTube. Number two in the series, Evil Dark, is on Angry Robot’s schedule for April 2012.

If this kind of crossover fiction is your kind of thing, here’s an anthology that’s chock full of them: Those Who Fight Monsters: Tales of Occult Detectives, edited by Justin Gustainis (Edge, 2011). I’ll list the contents (and detectives) as the first comment. (Some of these I already knew about, others I didn’t.)

Wed 10 Aug 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 5.2: Theatre of Crime (UK)

British television in the 1950s and 1960s seemed to be choking itself on claustrophobic, heavily-theatrical studio-based plays (often live, sometimes taped). The BBC seemed shackled to the home theatre approach while newcomer ITV (from late 1955) tended to favor young TV writers (the provocative Armchair Theatre, ITV, 1956-74, for example) alongside somewhat wild and adventurous themes (the early Honor Blackman period of The Avengers, ITV, 1961-69).

Themes or strands, usually explained by the title, such as The Villains (ITV, 1964-65), Blackmail (ITV, 1965-66) and Seven Deadly Sins (ITV, 1966) or by a general heading like Suspense (both ITV, 1960; and BBC, 1962-63) were very much in style during the 1960s, but I have disregarded many of these because they represent nothing more than simple crime-and-comeuppance yarns. It is sad to consider that over a decade later such predictable collections as the 1978 ITV series Scorpion Tales didn’t improve the British TV genre very much.

The mid-1960s even saw a brief fascination with the fogbound period of Gaslight Theatre (BBC, 1965) and Mystery and Imagination (ITV, 1966; 1968; 1970). At the same time reveling in the Victorian-era police procedurals of Sergeant Cork (ITV, 1963-64; 1966-68) or penetrating the pea-soupers of Sherlock Holmes (BBC, 1965).

Here I have focused on the more obvious or more interesting genre anthologies shown on UK television during the past half century. (Some of them may even be found on DVD via Amazon-UK or NetworkDVD.)

One of the earliest was Tales from Soho (BBC, 1956), Berkeley Mather’s less-than-serious take on the notorious central London area. A curious point of interest to emerge from this lightweight collection, however, was one Chief Detective Inspector Charlesworth (played by John Welsh) who went on to his own series. Now featuring Wensley Pithey as Scotland Yard Detective Superintendent Charlesworth, the series was called Big Guns (BBC, 1958). Mather followed up with Charlesworth at Large (BBC, 1958) and Charlesworth (BBC, 1959).

Something of an unexpected pleasure, Hour of Mystery (ITV, 1957) was hosted by the fearsome Donald Wolfit. Among the episodes were “The Man in Half Moon Street” (with Anton Diffring), “The Woman in White”, Emlyn Williams’ “Night Must Fall” and “A Murder Has Been Arranged”, and Ivan Goff & Ben Roberts’s “Portrait in Black” (filmed in 1960 by Universal).

Armchair Mystery Theatre (ITV, 1960; 1964-65) was the summertime replacement for the long-running Armchair Theatre and featured stories by Michael Gilbert (“The Blackmailing of Mr. S.”, 1964), Julian Symons (“The Finishing Touch”, 1965) and Mary Belloc Lowndes (“The Lodger” (1965).

British-made (at MGM British Studios) for producer Herbert Brodkin’s Plautus Productions (US), the filmed anthology Espionage (NBC/US and ITV/UK, 1963-64) was one of the more intelligent contributions to the then-raging 1960s spy cycle. The Larry Cohen-scripted “Medal for a Turned Coat” (starring Fritz Weaver) remains a particular favorite with this writer.

BBC’s mid-1960s anthology Detective (BBC, 1964; 1968-69) has in the eyes of fans achieved almost legendary status, perhaps due in great part to this 45-episode series being “missing believed wiped.” For now, I’ll list just a few episodes that gave rise to some fascinating series:

The episode “The Drawing” (1964), scripted by Gil North [Geoffrey Horne], featured North-country Detective Sergeant Cluff (played by Leslie Sands) and soon became the rather leisurely but enjoyable Cluff (BBC, 1964-65). The episode “The Speckled Band” (1964), needless to say, went on to become Sherlock Holmes (BBC, 1965) with Douglas Wilmer as Holmes and Nigel Stock as Watson; Peter Cushing took over as Holmes for a 1968 revival of the series. A third episode to spin-off from the anthology was “The Case of Oscar Brodski” (1964), from the works by R. Austin Freeman, and became the series Thorndyke (BBC, 1964) with Peter Copley as the methodical Doctor Thorndyke; this series, too, appears to be “missing believed wiped.”

Even while the legendary anthology Detective was enchanting grateful viewers, BBC’s Story Parade (1964-65) was lurking in the background with Ira Levin’s “A Kiss Before Dying” (1964) and, more importantly, Isaac Asimov’s “The Caves of Steel” (1964). This latter story featured the fascinating detective partnership of Elijah Baley (Peter Cushing) and the robot R. Daneel Olivaw (John Carson); depressingly, the original episode is said to no longer exist.

Outside of the 1960-63 Maigret series, BBC’s other celebration of Georges Simenon was captured in the non-Maigret collection Thirteen Against Fate (BBC, 1966). The collection was a stately-paced human condition drama, focusing on an individual in an unusual predicament; mercifully, the majority of these episodes have recently been rediscovered.

Leaning more on the horror and supernatural element, ITV’s very atmospheric Mystery and Imagination during the mid-1960s also found time to feature, among other dark mystery tales, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1966), Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Body Snatcher” (1966) and “The Suicide Club” (1970), and Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Uncle Silas” (1968).

Non-Sherlock Holmes stories made up Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (aka The Short Stories of Conan Doyle; BBC, 1967), a 13-part collection of stories ranging from the horror-fantasy of “Lot 249” to “The Mystery of Cader Ifan”. For the most part, the stories were dramatized by TV writer John Hawkesworth, who went on to immortalize Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock Holmes in the 1980s.

The series called Armchair Thriller (ITV, 1967) lasted a relatively short time but in its slight existence did manage to present Jack Trevor Story’s “In the Name of the Law” among its mere five outings. However, a more notable series under the same title (ITV, 1978; 1980) presented the six-part “A Dog’s Ransom” (1978) from the book by Patricia Highsmith, and the six-part “Quiet as a Nun” (1978) based on a book by Antonia Fraser (the first of a series of books that was spun-off as the 1983 series Jemima Shore Investigates for ITV). A six-part serial of Lionel Davidson’s “The Chelsea Murders” was also produced but not shown on UK TV until an edited version (condensed to 104 minutes) was broadcast in 1981. The Davidson novel was published in the U.S. in 1978 as Murder Games.

Starting off as a small series of plays under the ITV Playhouse: Rogues’ Gallery banner in 1968, including the wonderfully bawdy “The Lives and Crimes of Jonathan Wild and Jack Sheppard,” a six-part series called simply Rogues’ Gallery evolved in 1969 (ITV), featuring doom-laden tales of highwaymen and Newgate Prison.

Being recorded on icy-cold videotape didn’t somehow diminish the fascination of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (ITV, 1971; 1973). Among the compelling dramas were William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki in “The Horse of the Invisible” (1971), Baroness Orczy’s Lady Molly of Scotland Yard in “The Woman in the Big Hat” (1971) and Jacques Futrelle’s Van Dusen in “Cell 13” (1973). This series represented one of the most interesting and enjoyable collections to appear on UK television.

Alternating between the woman-in-jeopardy story and the supernatural-fantasy, Brian Clemens’ Thriller (ITV, 1973-76) was a passable series of 65- and 75-minute mini-movies (albeit videotaped). Moments of enjoyment could be had in edge-of-the-seat dramas such as the would-be pilots “K is for Killing” (US: “Color Him Dead”; 1974), with Gayle Hunnicutt and Stephen Rea as a couple of amateur sleuths, and “An Echo of Theresa” (US: “Anatomy of Terror”; 1973) and “The Next Scream You Hear” (US: “Not Guilty”; 1974), the latter two with Dinsdale Landen as the likeable but overly confident private investigator Matthew Earp.

Anglia Television in association with 20th Century Fox Television produced Orson Welles’ Great Mysteries (ITV, 1974-75), with the slouch-hat-and-caped one hosting some intriguing presentations of Conan Doyle’s “The Leather Funnel” (1974), Wilkie Collins’s “A Terribly Strange Bed” (1974), and Dorothy L. Sayers’ “The Inspiration of Mr. Budd” (1975). The series was curiously reminiscent of Hammer Films’ teaming with 20th Century Fox in 1968 for the collection Journey to the Unknown which, in the latter instance, was resolutely geared to scare the living daylights out of the viewer.

The 13-part thriller anthology with stories connected by the theme of the telephone, Dial M for Murder (BBC/Warner Bros, 1974), was invested with more imagination (by producer Jordan Lawrence) than most contemporary thriller series. While some presentations were indeed tedious, most of the stories were simply dripping with suspense. One of them, Julian Symons’s “Whatever’s Peter Playing At?,” attracted the attention as being just a notch above the average.

Somehow you knew that when Tales of the Unexpected (ITV, 1979-86; 1988) was shown as Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected during its early years it was inevitable that “Man from the South,” “Mrs. Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat” and “Lamb to the Slaughter” would be included.

Thankfully, the series also drew on stories by Stanley Ellin, Bill Pronzini, John Collier, Henry Slesar, Ruth Rendell, Helen Nielsen, Peter Lovesey and Patricia McGerr among many others. Even so, the general feeling was that it had all been done much better before in Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Some of the stories in The Agatha Christie Hour (ITV, 1982) were just plain silly and embarrassingly dated but most, when taken on their own level, were unexpectedly rewarding. The stories featuring the delightful Maurice Denham as Parker Pyne who runs a sort of dream-fulfilment agency are among some of the best. One of these Pyne stories was “The Case of the Discontented Soldier,” about William Gaunt’s retired-but-restless military major who is given his own Bulldog Drummond adventure; Lally Bowers also appeared in this story as Mrs. Ariadne Oliver.

Based on the works by the title author, The Ruth Rendell Mysteries (ITV, 1987-2000) consisted of some of the author’s crime thriller tales as well as her Detective Inspector Wexford stories (the latter series starring George Baker). Among the non-Wexford episodes the series presented the three-part “Vanity Dies Hard” (1995), in which a lonely woman investigates the disappearance of her friend, the two-part “The Secret House of Death” (1996), where a woman becomes involved in the sudden death of the neighboring couple, and “Thornapple” (1997), featuring a young boy embroiled in poisonings and inheritance.

Rating as something of a disappointment was the nevertheless interesting-sounding Frederick Forsythe Presents (ITV, 1989-90), a short-run espionage drama based on stories by the title author. While all the components seemed in order with some fine directors (Tom Clegg, Lawrence Gordon Clark, Ian Sharp) and top-notch players (Beau Bridges, Brian Dennehy, Lauren Bacall, Tony Lo Bianco) the anthology suffered from the “too many chefs” syndrome of having too many producers and co-production companies.

A similar fate befell another interesting collection, Mistress of Suspense (ITV, 1990; 1992), based on six (hour-long) stories by Patricia Highsmith. Something to enjoy and savor became instead a jumbled concoction due to its myriad producers and co-production companies.

Murder in Mind (BBC, 2001-2003) was a diverting anthology of psychological crime dramas written by the brilliant Anthony Horowitz. The series turned out to be one of the true delights of genre TV. Horowitz composed such spellbinding stories as “Motive,” where a married couple believe they have committed the perfect murder; “Flashback,” in which a barrister “defends” the man he has framed for murder; and “Echoes,” where a woman investigates the past when a centuries-old body is found in her garden. Told from the detailed perspective of the hunted (the criminal) rather than the hunter (police), Murder in Mind may very well have been one of the high points of British television crime drama.

Although I’m sure there are many interesting anthologies that I’ve overlooked or have simply forgotten, the previous Parts and the above should be regarded simply as a general overview.

The next Crime & Mystery Part intends to survey The Black Mask Style, the late 1950s private eye phase of 77 Sunset Strip, Richard Diamond, Mike Hammer and Peter Gunn.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

Part 5.0: Theatre of Crime (US).

Part 5.1: Theatre of Crime (Hours of Suspense Revisited).

Tue 9 Aug 2011

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

ROGER EAST – Murder Rehearsal. Knopf, hardcover, 1934. First published in the UK: Collins, hardcover, 1933.

When several “accidental” but suspicious deaths occur following the plot of Colin Knowles’s detective novel in progress, and one of those deaths could be advantageous to him in regaining his lost love, is Knowles turning art into reality? But why, then, the additional deaths?

Superintendent Simmonds of Scotland Yard is called in to investigate the first death and, later, with the help of Knowles’s unfinished novel, makes the connection with the other deaths in a book that combines the thriller and the detective story. If nothing else, this novel gives the reader the chance to re-encounter the greatly cherished delayed revenge motif, despite the necessity to swallow some large coincidences.

In the Manchester Evening Chronicle, Dr. Watson — frankly, I doubt that this was our Dr. Watson — said East “seems likely to become one of the small band of really first-class detective-story writers.” The promise is here, but it’s only a promise.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 3, Summer 1990.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

EAST, ROGER. Pseudonym of Roger Burford, 1904- ; other pseudonym: Simon.

The Mystery of the Monkey-Gland Cocktail (n.) Putnam 1932.

Murder Rehearsal (n.) Collins 1933 [Colin Knowles; Supt. Simmonds]

The Bell Is Answered (n.) Collins 1934.

Candidate for Lilies (n.) Collins 1934.

Twenty-Five Sanitary Inspectors (n.) Collins 1935 [Supt. Simmonds]

Detectives in Gum Boots (n.) Collins 1936 [Colin Knowles]

The Pearl Choker (n.) Collins 1954.

Kingston Black (n.) Collins 1960.

The Pin Men (n.) Hodder 1963.

SIMON. Pseudonym of Roger Burford & Henry Joseph Hasslacher.

Murder Among Friends (n.) Wishart 1933 [Insp. (Supt.) Deering]

Death on the Swim (n.) Wishart 1934 [Insp. (Supt.) Deering]

The Cat with the Moustache (n.) Wishart 1935 [Insp. (Supt.) Deering]

« Previous Page — Next Page »