December 2011

Monthly Archive

Sat 17 Dec 2011

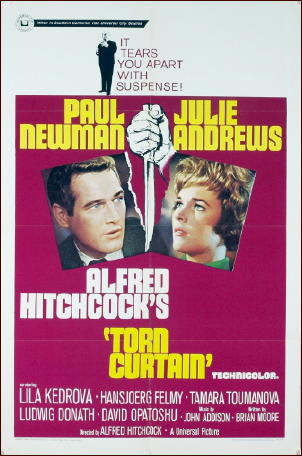

TORN CURTAIN. Universal, 1966. Paul Newman, Julie Andrews, Lila Kedrova, Tamara Toumanova, Wolfgang Kieling, Ludwig Donath, David Opatoshu, Gisela Fischer, Carolyn Conwell, Gloria Gorvin. Original music: John Addison. Director: Alfred Hitchcock.

This is generally considered to be one of director Hitchcock’s lesser successes, and I think I’d go along with that, but not necessarily for the same failures that other moviegoers (and critics) have seen.

My wife and I watched this the other evening on one of the Cinemax channels for the first time since it was first released. The funny thing is she didn’t remember it at all, and the scene I remembered, I only thought I did. This is the one in which Paul Newman (as a bogus turncoat physicist) is trying to obtain a secret formula from his counterpart in East Germany (Ludwig Donath) standing together at a blackboard in a deserted classroom.

You might call this dueling with chalk and erasers. At the time I thought the scene was hilarious, being a math student at the University of Michigan myself.

Erasing parts of equations and replacing them with bits and pieces of others: sines, cosines, vectors and tensors? It was fun to see at the time, and it was fun to see the other night.

What I didn’t remember was that this scene took place in such a small room. I remembered it happening in the large lecture room across the hall, and it’s funny what kind of tricks you mind plays on you. I have a feeling now that half the things that I remember happening to me over the years never happened the way I remember them, and it’s a eerie feeling, I can tell you.

Playing opposite Newman is another huge star at the time, Julie Andrews. She’s his assistant and bewildered fiancée who with great determination — and most definitely against his wishes — follows him on this grandly noble act of undercover academic espionage.

It is obvious that chaps like Newman who find themselves in capers like this really, really ought to tell their fiancées what it is that they’re doing. All that petty deceptions do — and the petty deceptions those deceptions require — is to make only bigger messes of everything, including escapes, when the time comes.

The script, then, it what I found to be the problem. Too much silly rigmarole in making contacts, et cetera, too little planning, too little communication, and I didn’t believe a word of it. Paul Newman is also too brooding – method acting? – and too self-centered.

If I were about to get married to someone who looked like Julie Andrews, I would do almost anything to make sure I didn’t mess it up. She acts like she cares for him; there’s no chemistry at all in return, no lights in his eyes the other way around.

Two big stars, then, not quite compatible, whose combined salaries left too little in the budget for a decent story, better matte shots, and less reliance on phony looking rear projection.

Which is not to say that Mr. Hitchcock lost his touch completely in making this film. Newman finds himself shocked at his first attempt at killing a man (Wolfgang Kieling, as the East German agent who discovers his double-dealing duplicity), a killing that is not at all easy – the scene that everyone agrees upon as being the standout, and the one most remembered, in the entire movie. It’s a dandy, all right, no doubt about it. This is the kind of scene you watch a Hitchcock movie for.

On the other hand, I liked Lila Kedrova’s performance as the expatriate Polish Countess Kuchinska even more, although a number of commenters on IMDB thought it one of the worst aspects of the film.

What dunderheads! (Figuratively speaking, of course.) Needing a sponsor to make her way out of East Germany and on to America, and having recognized Newman and Andrews as spies on the run, she is torn between coyly requesting and silently pleading for them to help — trying desperately to keep her emotions from showing on her face and not succeeding.

Newman (as is his wont throughout the movie) is stolidly not impressed by this small petty form of blackmail. It is Julie Andrews’ character who is won over. Good for her! This is the scene that I will remember now until the time I shall see the movie again.

Sat 17 Dec 2011

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

THURMAN WARRINER – Method in His Murder. Macmillan, US, hardcover, 1950. First published in the UK: Hodder & Stoughton, hardcover, 1950.

“Unquestionably, if Rhoda had been his wife, Mr. Ambo would have contemplated murder.” Ambo’s godson, John Wainfleet, who is married to Rhoda, contemplates nothing but a life of obedience to her demands.

Or so it seems, until he reveals to Ambo that, after producing a satirical crime novel that had a modest success and a play that was still going strong, and after being told by Rhoda that he would have to stick to being a solicitor, he has a secret life in which he lives, though perish the thought not in sin, with another woman two days a week and writes successful novels under a pseudonym.

Things are in this state temporarily, and then Rhoda’s brother ostensibly dies in an auto accident. The young doctor who examines the corpse believes death occurred before the accident, and apparently so do the police.

Wainfleet and another man who were with Rhoda’s brother before the accident have perfect alibis. Well, Wainfleet does until Ambo starts investigating and discovers more than he wants to.

This is the first novel featuring the investigations of Charles Ambo; Archdeacon Grantius Fauxlihough Toft, an unusual clergyman who believes in the Devil and burglary; and John Franklin Cornelius Scotter, private investigator. It is well worth discovering by those who enjoy humor, a fine prose style, and three engaging characters.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 4, Fall 1990.

Bibliographic Notes:

The Ambo, Toft & Scotter series —

Method in His Murder (n.) Hodder 1950.

Ducats in Her Coffin (n.) Hodder 1951.

Death’s Dateless Night (n.) Hodder 1952.

The Doors of Sleep (n.) Hodder 1955.

Death’s Bright Angel (n.) Hodder 1956.

She Died, Of Course (n.) Hodder 1958.

Heavenly Bodies (n.) Hodder 1960.

Only the first of these was published in the US. Warriner wrote one other mystery under his own name, another twelve as by Simon Troy, and one as John Kersey. Inspector Charles Smith appeared in all but one of the Troy books, the most well-known probably being Road to Rhuine (1952), and had a cross-over appearance in She Died, Of Course above.

Fri 16 Dec 2011

THE FRONTIER WHODUNIT THAT WASN’T

A Review by Mike Tooney

“The Accused.” An episode of Daniel Boone (1964-70). Season 2, Episode 27. First airdate: March 24, 1966. Fess Parker, Joanna Moore, Ed Ames, Ken Scott, Vaughn Taylor, E. J. Andre, George Savalas. Writer: David Duncan. Director: John Florea.

Daniel Boone (Parker) gets into real trouble when a man he has just been dickering with over the price of furs ends up being murdered.

Every bit of circumstantial evidence points to Daniel, but being a scrupulously honest individual, he allows himself to be jailed even after an inquest clinches his guilt. Things aren’t helped at all by the inflexible attitude taken by the local constable.

Of course, Daniel didn’t do it, as his Oxford-educated Cherokee friend Mingo (Ames) knows instinctively. Not being one to see injustice done, Mingo springs Daniel from the hoosegow and the two set out to find the real perpetrators.

…which they eventually do, but only after a lot of running and jumping and shooting of the sort you won’t find in a typical Perry Mason episode.

Which brings us to the chief defect of this particular show: that, with just a little rearranging, it would have made a grand whodunit, instead of the more prosaic how’s-he-gonna-clear-himself type of plot.

The viewer knows ab initio what happened, who did the crime, and how they attempted to cover it up — and this knowledge contributes nothing to the progression of the storyline.

If the producers had taken the first five tell-all minutes of the episode and simply moved them to the end, at the point when the perps have been apprehended and are explaining how and why they did the dirty deed, this commonplace action adventure show could have been elevated to a higher plane — a genuine whodunit.

By inserting closeups of more of the people with worried expressions at the inquest — Perry Mason-style — and snipping a scene or two later on, the mystery would have been sustained.

But by not doing so, the writer and the director missed a golden opportunity to give us a real rara avis indeed, a buckskin whodunit. Thus, the best moments in the show must remain the final few funny minutes when Daniel and Mingo are stranded literally up a tree.

We’ve already discussed Joanna Moore in a couple of previous Mystery*File entries here and here, as well as Fess Parker here.

If writer David Duncan’s IMDb filmography is complete, the notion of writing a mystery was foreign to him.

And, yes, that’s Telly Savalas’s younger brother George (1924-85) playing the warden. Usually billed as “Demosthenes” (his middle name), he appeared in 114 episodes of Kojak.

Thu 15 Dec 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

ANDREW GARVE – The Ascent of D-13. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1969; Harper, US, hardcover, 1969. Reprint paperbacks include: Popular Library, 1968; Perennial Library, 1986.

— Two If By Sea. Harper, US, hardcover, 1949; first published in the UK as Came the Dawn, Hutchinson, hardcover, 1949, both as by Roger Bax. Reprint paperback: Perennial Library, US, 1986, as by Andrew Garve writing as Roger Bax. Film: MGM, 1953, as Never Let Me Go (with Clark Gable & Gene Tierney).

It’s good to see Garve being reprinted, and, these two books, published almost two decades apart, will serve as a splendid introduction to a writer who wrote more than thirty novels, no two of which seem cut from the same pattern.

The only similarity in these two, books is that both are about the Cold War and both are genuinely exciting and suspenseful. In The Ascent of D-13, rival Western and Russian mountain climbers “race” up a rugged peak on the Turkish-Armenian border to recapture, a secret weapon on a plane which has crashed.

Two If By Sea, which Garve originally published in 1949 as by Roger Bax, grabs the reader quickly with its tale of a British correspondent’s efforts to rescue his Russian wife from behind the Iron Curtain. Garve’s effective use of a sailing background is a bonus.

NICHOLAS GUILD – Chain Reaction. St. Martin’s, hardcover, 1983. Berkley, paperback, 1986.

Forget you know the results of World War II. This is one of those books in which the author wants you to guess whether Herman Goering will throw out the first ball at the 1946 World Series.

Actually, it starts out well enough as in January 1944, an anti-Nazi, but loyal, German officer is landed in New England on a mission which can possibly save Hitler’s beleaguered War effort.

The early chapters are quite good, but then evidence of careless writing and poor research (frequent anachronisms) creep in. There is a switch in character focus midway which weakens things even further, so that by the end we really don’t care how the book will end.

Incidentally, this was a book with eleven swastikas on the cover. That, alone, should have deterred me from reading it.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 8, No. 4, July-Aug 1986.

Thu 15 Dec 2011

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Within five months, five deaths: my wife, my youngest brother, my longtime agent, my editorial partner on the “Mystery Makers” series, and the secretary without whose gentle mentoring I’d still be batting out words on a manual typewriter. I’ll never remember this year fondly. But before it closes, and before next January 6 when I collide with my 69th birthday, I’d like to begin writing again.

In a column that dates back to before any of those deaths, I mentioned that some of the music Bernard Herrmann wrote for the earliest episodes of the CBS Adventures of Ellery Queen radio series could be seen on the Herrmann Society website. Now it can be heard too. If you go to www.filmscorerundowns.net and then click on “CBS Audio Clips,†you’ll be able to listen to 21 Herrmann excerpts, most of them unavailable elsewhere.

Two of the three earliest come from the 60-minute Ellery Queen episode “The Last Man Club†(June 25, 1939) and the third from “The Impossible Crime†(July 16, 1939), all three performed on a synthesizer by David Ledsam. Even without the original instrumentation, the 31-second Cue 1 from “The Last Man Club†is instantly recognizable as Herrmann, although the other two lack the uniquely ominous sound that he became famous for.

But it’s hauntingly present in the vast majority of these 21 audio clips, and anyone who listens to all of them will perhaps understand why I’ve called Herrmann the Cornell Woolrich of music.

You can listen to dozens more audio excerpts, many from legendary TV series like Perry Mason and Have Gun Will Travel and Gunsmoke, if you visit www.bernardherrmann.org and then click on “Herrmann CBS Legacy.†Both of these centenary tributes to perhaps the greatest of all film composers were prepared and arranged by Herrmann authority Bill Wrobel.

As chance would have it, Herrmann and Queen interfaced again almost a quarter century after the Queen radio show debuted. “Terror in Northfield†(October 11, 1963), one of 17 episodes of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour with original Herrmann scores, was based on a non-series novelet by Queen.

Herrmann’s music for that and eight other episodes of the series is available on three CDs in the recently released Varese Sarabande set The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, Volume Two, which I recommend highly.

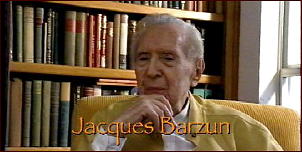

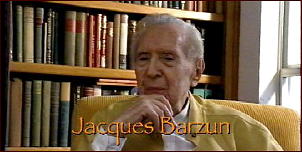

November 30 of this year marked the 104th birthday of the world-renowned historian of ideas Jacques Barzun, who in the early 1920s was a classmate of Woolrich at Columbia University and to whom we owe everything that is known about the young manhood of the Hitchcock of the written word.

My first contact with Barzun was in the late Sixties when I arranged for his essay “Detection and the Literary Art†to be reprinted in my anthology The Mystery Writer’s Art.

We met in 1970 when I was living in New Jersey and working on the Woolrich collection Nightwebs. Barzun invited me to his office in Columbia’s Low Library and spent the better part of an afternoon describing for me what the university was like in the years immediately after World War I and also, of course, what the young Woolrich was like.

The factor that seems to have brought the two together was that they were the only members of their class who had spent most of their lives outside the United States, Barzun in France and Woolrich in Mexico with his father.

Their friendship came to an end when Woolrich sold his first novel to a major publisher while in junior year and quit Columbia under the delusion that he was about to become the next F. Scott Fitzgerald. He wound up one of the founders and the supreme practitioner of the dark suspense genre we now call noir.

Woolrich’s brand of desperate anguish was not Barzun’s cup of tea. His mammoth Catalogue of Crime (2nd ed. 1989) makes it clear that he much preferred humdrum English authors like John Rhode.

I had read some Rhode and also another humdrum Brit signing himself Miles Burton, and had noticed something very strange about both sets of books. Whenever a character asks a question of another, the verb following the second character’s line of dialogue is always the same. Always.

Hundreds of times in each book, hundreds of thousands of times in the complete works. “ABC?†asked Inspector Boothbridge. “XYZ,†Lord Wychthorpe replied. “One two three?†Dr. Coxcroft inquired. “Eight nine ten,†Mrs. Hornbeam replied.

The obvious conclusion is that Rhode and Burton were the same man, but apparently no one had mentioned it before me (in The Armchair Detective for October 1968). At any rate Barzun in Catalogue of Crime credited me with the discovery.

Among those who weren’t aware of the Rhode-Burton identity was Anthony Boucher. He thought most of the Rhode books dull but usually reviewed them soberly, while the Burton novels he ridiculed and detested. Here’s his complete review of Death at Ash House from the San Francisco Chronicle for December 6, 1942:

“Inspector Arnold plods through the problem of the bashed secretary and at last catches up with the reader. Relentlessly painstaking — and giving.â€

Here’s what he had to say about Accidents Do Happen in the Chronicle for February 10, 1946:

“A famous editor [I suspect he means Simon & Schuster’s Lee Wright] once said, ‘No American mystery can be so dull as a dull British, and no British as bad as a bad American.’ Mr. Burton gives her the lie. Not only is his latest dull, endless and snobbish; its ending (one can hardly say solution) provides the most incompetent detecting … of the past decade — bad enough to make the brashest American quickie seem well plotted.â€

These and three more snarky reviews of Burton can be found in The Anthony Boucher Chronicles (2001). Burton’s American publisher dropped him before Boucher took over as mystery critic of the New York Times but they continued to appear in England until 1960.

The Rhodes kept coming out on both sides of the Atlantic and Boucher reviewed all of them, perhaps because as a Catholic he thought he should do penance for his sins. I remember he called one of them “the dreariest Rhode I have yet traversed.†I can’t recall anything about the book of which he said it.

Wed 14 Dec 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

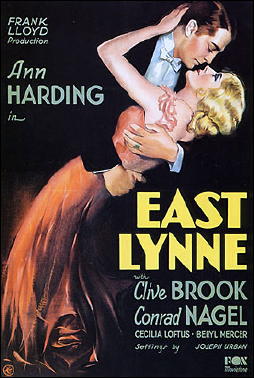

EAST LYNNE. Fox, 1931. Ann Harding, Conrad Nagel, Cecilia Loftus, Clive Brook, O. P. Heggie, Eric Mayne, Beryl Mercer, Flora Shefffield, David Torrence. Based on the play by Mary Elizabeth Braddon, and the novel by Mrs. Henry Wood. Art director: Joseph Urban; cinematographer: John F. Seitz. Director: Frank Lloyd. Shown at Cinecon 39, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2003.

A fairly sizable portion of the audience decamped after the McCarthy interview, but memories of an enjoyable silent version of East Lynne starring Theda Bara (1916) kept me in my seat for this sound remake.

The play on which both films were based was one of the most popular of Victorian melodramas. Ann Harding, as Lady Isabella, a London socialite, marries Nagel, a country solicitor.

When they arrive at Nagel’s estate, Harding finds the household managed by his sister Cornelia (chillingly played by Cecilia Loftus) and even after the birth of a daughter, the power still resides in the sister, with Harding an uncomfortable and unaccepted subordinate.

The arrival of an old friend (and former suitor) of Harding leads to her first display of opposition, an ill-advised move that results in her being sent from the house by her husband and eventually becoming the mistress of the former suitor (Clive Brook), with a life that spirals down into poverty.

The climax pulls out all the dramatic stops (blindness, a possibility fatally ill child, vindication, penance and death). I will discretely lower the curtain on the specific plot details.

Brook as the cad and Loftus as the possessive, vindictive sister gave performances that brought the film to intermittent life. Nagel’s profile was prominently featured.

I’ve always found Harding to be a very controlled actress who didn’t inspire much feeling in me about her performances. That probably worked to the film’s advantage since it reined in some of the excesses of the plot.

The film was handsomely staged (Joseph Urban was a notable production designer) and photographed. I still prefer the Bara version, but Victorian melodrama isn’t far from modern soapers, and a classy rendition still had the power to engage the sensibilities of at least some members of the audience.

Editorial Comment: This movie version of East Lynne was nominated for an Oscar as Best Picture of the Year.

Tue 13 Dec 2011

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

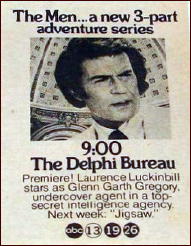

THE DELPHI BUREAU: THE MERCHANT OF DEATH ASSIGNMENT. TV-Movie Pilot for the ABC-TV series The Delphi Bureau. March 6, 1972. Warner Brothers. Two hours. CAST: Laurence Luckinbill as Glenn Garth Gregory, Celeste Holm as Sybil, Cameron Mitchell as Stokely, Joanna Pettet as April, Bob Crane as Charlie, Dean Jagger as Keller, Bradford Dillman as Jamison. Written and Produced by Sam Rolfe. Directed by Paul Wendkos.

When surplus fighter planes begin to disappear, the President asks the top secret Delphi Bureau to find them. The Bureau is so secret it has no office, no record of existing, and, as far as its agent Glenn Garth Gregory knows, it has only two employees, him and his boss, Sybil, a Washington DC society hostess.

Gregory is a researcher with a photographic memory and a dislike for danger. So he is quite upset when, after he discovers how the planes were taken, a fake cop tries to kill him. Sybil is less than sympathetic, and once they figure out where the planes may be hidden, she sends Gregory there, a large experimental farm outside a small town in Kansas.

But first, Sybil tosses a party so Gregory, posing as an agricultural expert from the Department of Agriculture, can meet the prime suspect, Matthew Keller. Keller is a former arms merchant now an invalid and obsessed with farming and feeding the hungry, and surrounded by a mixed group of people. There is beautiful April who tries to warn Gregory away, the friendly therapist, terrified Jamison, and Stokely, a killer so cool he winks at Gregory when Gregory recognizes him.

“That chauffeur is the fake cop that tried to kill me!” a panicked Gregory tells Sybil.

“He didn’t do a very good job, did he?” she replies.

“He’ll know I’m not an agricultural expert.”

“Well, that’s only fair. You know he’s not a cop.”

Writer-producer Sam Rolfe (Have Gun Will Travel, Man from U.N.C.L.E.) deserves to be better remembered for his work in television. Rolfe’s Glenn Garth Gregory did to the spy genre what James Rockford did to the PI genre. Both series enjoyed twisting almost mocking the tropes of the genre.

Gregory was no dashing James Bond nor satirical Flint nor comedic Maxwell Smart. Glenn Garth Gregory was just a researcher. Granted a researcher with a photographic memory that gave him an encyclopedia in his head and the ability to escape traps that would rival MacGyver.

The plot was played basically straight but with Rolfe’s usual touches of humor in the dialog and characters. There was a better than average TV mystery solved by Gregory advancing through twist after twist, discovering clues along the way, and falling into and escaping trap after trap.

Luckinbill was convincing as the researcher forced to play spy to keep his job and its many rich benefits. Celeste Holm makes you believe her flighty society hostess character was also a tough spymaster as heartless as Bond’s M. Even the bad guys were fun, especially Cameron Mitchell’s remorseless killer Stokely and Brad Dillman’s neurotic Jamison.

Perhaps the most unusual part of the show was a running limerick that bridged commercial breaks, one line at a time until the end when the limerick would be completed.

From the capital came a young man…

To uncover some worms in a can…

So they con him – they frame him…

For murder they blame him…

In turn – he eludes them…

Pursues – then eschews them…

’Till he holds all the strings to the plan…

The end – more or less, Delphian!

The Merchant of Death Assignment would lead to the series The Delphi Bureau which premiered in October 1972 and shared a time slot with Assignment: Vienna and Jigsaw under the umbrella title of The Men.

The Delphi Bureau lasted only eight one-hour TV episodes. It was then, and remains today, one of my favorite TV series.

Neither the pilot nor the series is currently available on DVD or online. A very poor quality video of the opening sequence of the series can be found here on YouTube, while a two-minute segment from the pilot was posted there by Laurence Luckinbill a couple of years ago.

One can only hope Warner Archives, that has blessed us with Made On Demand DVDs of the TV-Movie pilots Probe (Search) and Smile Jenny, You’re Dead (Harry O) will do the same for The Merchant of Death Assignment (The Delphi Bureau).

Tue 13 Dec 2011

Reviewed by RICHARD & KAREN LA PORTE:

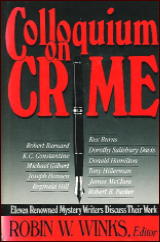

ROBIN W. WINKS, Editor – Colloquium on Crime: Eleven Renowned Mystery Writers Discuss Their Work. Scribner’s, hardcover, 1986; softcover, August 1987.

Col-lo-qui-um: an informal conference or group discussion.

Mr. Winks, who goes by the resounding title of “Randolph W. Townsend, Jr.” at Yale, wrote to his fifteen favorite living authors, and eleven replied with short commentaries on their journeys into the realm of crime fiction.

Robert Barnard talks of detective stories as a form of entertainment and has a prejudice for their being “well plotted, fast and ingenious.” Rex Burns comments that “mystery writing is the paradox of an art form that, while working within its own strict formal requirements, attempts to recreate the effect and appearance of contemporary life with its everyday formlessness.”

K. C. Constantine says “I started writing crime fiction because I’d had no success selling anything else I’d written.” He certainly had to go on from there as his small town cop Mario Balzic is classic. After him comes Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Michael Gilbert and Donald Hamilton, whose essay is entitled “Shut Up and Write.”

Joseph Hansen explains why he chose a gay investigator in the “uptight” insurance field as his series detective. Tony Hillerman discusses the fine art of mixing anthropology with the arcane procedures of the Navaho Tribal Police. Reginald Hill talks about how he develops the scenes of his stories from his own experiences.

James McClure says “Discovery is a vital part of writing for me.” He once plotted and outlined himself into a writer’s block. And finally… Robert B. Parker is quoted as being “an Apostle of the possible.”

The one thing that is very evident from these essays and from Mr. Winks’s commentary on them is that writers read. They read heavily, thirstily and, most of all, with perception, enjoyment and understanding. We hope all of our readers will follow their leadership.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 7, No. 1, Fall-Winter 1987.

Tue 13 Dec 2011

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“Back for Christmas.” An episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Season 1, Episode 23. First airdate: March 4, 1956. John Williams (Herbert), Isabel Elsom (Hermione). Teleplay: Francis M. Cockrell, based on the story by John Collier (The New Yorker, 1939). Director: Alfred Hitchcock.

While there are eleven speaking parts in this teleplay, only two really matter: Herbert, the put-upon, repressed husband (masterfully underplayed by quintessential British actor John Williams), and his officious wife Hermione (Elsom).

Our first impression is aural: the sound of someone digging. It’s Herbert, ostensibly excavating an area for a wine cellar.

When Hermione comes down to check on him, the camera pans and lingers over her in a subjective POV shot from Herbert’s point of view. Later, Hitchcock will give us another long, lingering POV shot of Hermione as the couple are entertaining friends. In both instances, Herbert’s face all but telegraphs his intentions — but no one, especially Hermione, seems to notice.

Once Herbert hefts an iron pipe, looks sideways at his wife, and — when she has gone back upstairs — checks his passport to confirm how tall she is compared to the hole he’s digging, the audience member who hasn’t caught on by now to what he’s planning really should be ashamed of himself.

Like anyone who has carefully planned to commit a crime, Herbert has been meticulous almost to a fault — but also like most premeditating criminals, Herbert fails to allow for the unexpected….

Not to be confused with the American music composer of the same name, John Williams (1903-83) was one of Alfred Hitchcock’s favorite actors. He appeared ten times on Alfred Hitchcock Presents from 1955-59.

Prior to that, he had won a Broadway Tony Award for playing Chief Inspector Hubbard in Dial M for Murder (1953), a role he would reprise for Hitchcock’s film version (1954), in which he delivers the memorable line: “They talk about flat-footed policemen. May the saints protect us from the gifted amateur.”

Williams also had a substantial supporting part in To Catch a Thief (1955), dogging jewel thief Cary Grant for most of the film. And he was a pivotal character in the Thriller series adaptation of Robert Bloch’s “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” (1961), ironically an episode directed by Ray Milland, the killer he brought down in Dial M for Murder.

No suprise that he would be cast as William Shakespeare in a Twilight Zone episode (1963), frequently and ostentatiously quoting … himself.

John Collier (1901-80) has 27 credits on the IMDb, including seven Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1956-61), one Alfred Hitchcock Hour (1964), and six Tales of the Unexpected (1980-85), among them a remake of “Back for Christmas.”

The original “Back for Christmas” can be viewed on Hulu here. A fairly detailed discussion of this episode can be found at Senses of Cinema here.

Sun 11 Dec 2011

ADVENTURES IN COLLECTING:

Is Completism Fatal?

by Walker Martin

Dear Walker:

My own collection is all but complete — meaning that I’ve almost acquired all of the items on my want list. Of course I’ll always be out there keeping my eye open for serendipitous books and magazines, but I only have a very few more such items that I’m actually looking for. Once I find those I’m essentially done. Then I’ll just give them all away to the Salvation Army thrift store and start over… Your advice, please!

— C.P.

Dear C.P.

You have touched on a dangerous subject that all serious collectors must beware. I’ve seen many collectors fall into the dreaded trap of completing their collection. Usually once the collection is completed then many collectors lose interest and start thinking what next?

This results in the selling off of many collections because the enthusiasm of the chase and the drive to collect is now finished. Collectors that limit themselves to a favorite author or magazine are prone to losing interest once their goal of completion has been achieved.

Since collecting can be so much fun, how do we avoid falling into the abyss and losing interest in our collections after completion? The answer I have found is very simple, you do not allow yourself to complete your collection. You have to keep expanding your interests.

For instance, in your case, if you are close to completing your SF wants, then you have to develop an interest in another genre, another subject, other magazines. Maybe detective fiction or adventure pulps or original art to go along with your SF collection. Something else!

For instance in my own case, I started off in 1956, at the age of 13 collecting SF. This continued for around 10 years until I discovered detective pulps thanks to Ron Goulart’s Hardboiled Dicks anthology. This led me to collecting all sorts of mystery fiction like Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Ross Macdonald. It led me to completing sets of such great magazines like Black Mask and Dime Detective.

But then around 1980, I was faced again with the horrifying realization that I was nearing completion of the detective and mystery wants. I quickly expanded to adventure and western fiction and started to work on extensive sets of Western Story, West, Short Stories, Adventure, All Story, Argosy, Blue Book, Popular, Sea Stories and many others.

As I started to complete these magazines and run out of reading matter, I decided my job was taking up too much of my time and interfering with my reading and collecting activities. So in 2000 I retired to concentrate on building up what may be the world’s largest collection of literary magazines.

I’ve yet to meet another collector that is interested in these artifacts, but I love them, and I can fall into a trance looking and smelling the scent of rows and rows of literary quarterlies like the Hudson Review, The Criterion, Scrutiny, The London Magazine, Kenyon Review, Paris Review, and The Virginia Quarterly. I could go on and on forever but I’m sure you are all disgusted and fatigued reading about someone else’s collecting addictions. Hell, I actually read these things.

But the end may be near, even for me. I’ve mentioned before about almost being crushed by the collapsing of one of my basement bookcases due to overloading. Then a year or so later several bookcases fell on top of me and my son. Then last month a bookcase of literary magazines showered me with more than a hundred issues of the Sewanee Review.

It was heavenly. I just stood there as the magazines rained down on me and I felt at peace. Then I had to go to work picking them up off the floor and stacking them before my wife came to investigate the noise. She’s heard the sound of collapsing shelves and stacks falling, so she never asked me until a couple days later about the crashing noise that she chose to ignore.

Probably, she was hoping that I had tempted fate once too often and had been pounded flat as a pancake by the old magazines that she now hates with a passion. But no, I survived once again, just like some pulp super hero!

So I say to you, C.P., don’t stop collecting. There are unknown fields still to conquer. Don’t spend all your salary on your bills, your family, college fees for your children. You work hard for your money; spend some of it on collecting!

Now I have to go back to a discussion I’ve been having with myself for 50 years. What is the greatest fiction magazine ever? Is it Adventure in the 1920’s, All Story in the teens, Black Mask and Weird Tales in the 1930’s, Astounding and Unknown in the 1940’s, Galaxy in the 1950’s and 1960’s?

How about The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which has to fit somewhere. How about the SF fiction in Playboy and Omni, or the mystery fiction in Manhunt or EQMM?

Maybe I better fix up these bookcases so they don’t collapse; I need answers to the above questions!

Previously in this series: Collecting Manhunt.

« Previous Page — Next Page »