January 2012

Monthly Archive

Thu 26 Jan 2012

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

MURDER BY CONTRACT. Columbia Pictures, 1958. Vince Edwards, Phillip Pine, Herschel Bernardi, Caprice Toriel, Michael Granger, Cathy Browne. Director: Irving Lerner.

Incredibly cheap, unbearably compelling, with Edwards an emotionless Hit Man who is gradually revealed as hopelessly hung up on the trivial details he thinks will become his undoing.

Story and dialogue are terse and to-the-point as a speeding bullet, and the whole thing is filmed by Lucien Ballard (the second-best Cheap Cameraman in Hollywood) with an eye for Garish Modern that seems unusually perceptive for its time but was probably merely a matter of having to work on Location.

This is cold, precise film-making at its very best and I recommend it highly.

Editorial Comment: Murder by Contract is easily available on DVD. It’s one of the films included in the recent box set Columbia Pictures Film Noir Classics, Vol. 1 (The Big Heat / 5 Against the House / The Lineup / Murder by Contract / The Sniper).

Thu 26 Jan 2012

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Thomas Baird

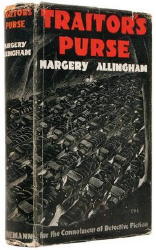

MARGERY ALLINGHAM – Traitor’s Purse. Doubleday Crime Club, US, hardcover, 1941. First published in the UK: Heinemann, hardcover, 1941. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback.

England is at war. The country is threatened by a catastrophic stroke, and time is desperately short. All lines of investigation have gone slack, and only one man knows the enormity of the situation. Only one man has the faintest clue to the heart of the conspiracy. As the story opens, Albert Campion awakes in a hospital bed with total amnesia from a blow to the head.

Hearing himself described as the killer of a policeman, he recklessly escapes and heads for the Bridge Institute, a research organization that is “a living brain factory.” The Masters of Bridge are a hereditary group who are the governors of the Institute, and Sir Henry Bull is one of the Senior Masters. When the secretary to the masters is killed, the police question Campion, who was the last man to see him alive.

Campion’s investigations are invested with the psychology of paranoia. He walks a tightrope, of sifting clues while trying to reestablish his memory. Stanislaus Oates, head of the CID, has disappeared, and Campion can’t confide his memory loss to his love interest, Amanda, because of her trust in him.

The only really practical help that comes his way is from his man, Magersfontein Lugg, who recognizes what a blow to the head can do and protects Campion from the police manhunt and from the gang of criminals on his track.

The search for the traitor weaves through the criminal conspiracy and the institute itself (and by extension into the government) and leads into the cavernous heart of Nag’s Head, the rocky headland that looms over the town of Bridge.

Many characters appear, disappear, and reappear throughout the saga, including friends and relations; the policemen Oates, Yeo, and Luke; and the spymaster L. C. Corkran.

This story is Campion’s trial by fire — afterward he is a changed man. Later in his career, he has less to do and becomes a sort of consultant.

After Allingham’s death, her husband continued the Campion adventures in three more novels. One novel that has received much critical approval, The Tiger in the Smoke (1952), in some ways seems overdrawn and overwritten.

Other recommended titles by Allingham are Mystery Mile (1930), Look to the Lady (1931), Sweet Danger (1933), and More Work for the Undertaker (1948). Inducements to read them include the memorable names of characters, both major and minor, and of the various settings. And if you’re a fan of that Golden Age staple, a proper plan or map of the scene, these provide cartographic delight.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 25 Jan 2012

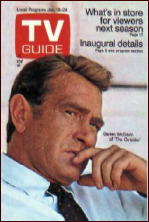

A TV Movie Review by Michael Shonk

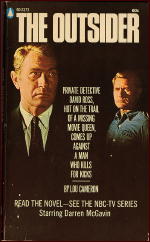

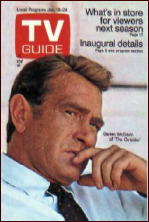

THE OUTSIDER. Made for TV “World Premiere” movie. NBC-TV/Huggins-Universal Productions, 21 November 1967. Cast: Darren McGavin as David Ross, Edmund O’Brien as Marvin Bishop, Sean Garrison as Collin Kenniston III, Shirley Knight as Peggy, Nancy Malone as Honora, Ann Sothern as Mrs. Kozzek, Joseph Wiseman as Ernest, Ossie Davis as Lt. Wagner. Music: Pete Rugolo. Director of Photography: Bud Thackery. Written and Produced by Roy Huggins. Directed by Michael Ritchie.

The Outsider is a story suitable for Black Mask magazine, a noirish tale of a loser PI on a simple case that spins out of control with a lying client, violence, betrayal, drugs, seedy L.A. music club life, a femme fatale, and doomed characters.

The story opens (as will the later series episodes) with David Ross narrating over an action scene that takes place later in the story. Ross is in a car driven off a cliff. He survives and the narration says, “My name is David Ross, and you may be wondering how I got into a situation like this.â€

Flashback to the beginning. Rich business manager Marvin Bishop hires PI David Ross to find out if one of his employees, Carol is stealing from him.

After spending the night trailing Carol, Ross is woken early by his client. Bishop is less than impressed by Ross. But Ross makes no apologies for his rundown apartment, that he is broke, never finished high school, has no office or secretary, and drives an old car.

He tells Bishop about trailing Carol to a jazz club where she met her boyfriend Collin. Collin has no past beyond a few years ago when the cops caught him shaking down homosexuals.

That night Ross walks into a trap. Collin uses a garrote on him and tries to learn why Ross is tailing them. Carol panics, spoils the trap, and the two run. Shortly after, Ross finds Carol dead in her bedroom. After he calls the cops, the phone rings, it is Collin.

Ross picks up his rich girlfriend Honora, an expert in L.A. club scene. Honora knows Ross will never marry, that would mean joining the world and Ross will always be an outsider. They search for Collin and find him at a Rock music club. Ross and Collin fight. Ross leaves the unconscious Collin for the cops and heads to question his client.

Bishop is unhappily married, and was having an affair with Carol. He had really hired Ross to learn if she was cheating on him. Bishop claims he did not kill Carol.

Cops question Ross. Collin has an alibi. The cops then discover Ross had served six years in prison for killing a man. Ross explains he was 19 and riding freight trains when a yard bull caught him and started to beat him with a nightstick. Ross hit him once killing the man. He had received a full pardon.

Ross has no idea what Collin is up to or who killed Carol. But Collin is equally curious about Ross. Ross finds Collin while Collin and the femme fatale are in the middle of an LSD trip supervised by Ernest the drug guru while Collin’s Mom watches TV game shows. But once available, Collin refuses to answer Ross’ questions.

Frustrated, Ross returns home. Bishop arrives and tells Ross to drop the case. Ross refuses. Bishop leaves and is shot at the bottom of the stairs.

The cops question Ross, but after a phone call, let him go.

Ross returns home knowing Collin is waiting inside, when Ross outsmarts Collin, the femme fatale knocks Ross out from behind. They think he is dying and panic. They take him to the cliff for the scene from the opening as they send Ross and car over the cliff.

There is a short gunfight. Ross then drives away with the femme fatale. He promises to help her escape if she tells him everything. She does. What she and Collin were doing had nothing to do with Carol’s murder and Bishop’s shooting. Ross hears on the car radio the cops have caught the killer. Ross takes the femme fatale to the cops. She reminds him of his promise to let her go. To which he happily replied, “I lied.â€

Roy Huggins (Maverick, Run for Your Life) was at his best here as writer and producer. His dialog was as hardboiled as Philip Marlowe and the handling of the club scenes and drug use was less melodramatic than usual for TV. The Outsider also featured many examples of Huggins odd humor, such as Ross keeping his telephone in the refrigerator.

Director Michael Ritchie (Prime Cut, Fletch) captured the noir style with a mix of 60’s b&w psychedelic style. He was nominated for a DGA award for this TV Movie.

Darren McGavin (Mike Hammer, Kolchak: The Night Stalker) carried this movie as the admirable loser PI David Ross, a character without ego and comfortable with his limitations.

The Outsider TV Movie was part of an experiment by Universal and NBC looking for better ways to find TV series. Universal’s “World Premiere†movies were a test for the 100-minute (plus commercials and stuff) format as a pilot. It resulted in three new series for NBC’s 1968 fall schedule, Dragnet 1967, Ironside, and The Outsider.

In the book TV Creators: Conversations with America’s Top Producers of Television Drama by James L. Longworth (Syracuse University Press, 2002), Huggins discussed why he refused to be involved with The Outsider TV series:

“After I shot the film, we had so much trouble editing out the “s†factor. That was short for “shit†factor … and although I really liked our star, Darren McGavin, he’s a nice guy, I just didn’t want to go through that. So I not only never had anything to do with

The Outsider, but I never even saw it.â€

The “shit†factor was most likely the growing concern over violence on television. Huggins was wise to avoid the headaches that Gene Levitt would experience when he produced The Outsider series.

Next time, we will examine The Outsider TV series.

Wed 25 Jan 2012

TIM MYERS – Room for Murder. Berkley, paperback original, September 2003.

If you haven’t read any of the previous ones in the series — and this is the fourth so far — Alex Winston is an innkeeper, and he helps solve mysteries. What’s unusual about the inn is that it’s next to an exact replica of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, but snugly nestled in the scenic Blue Ridge Mountains, way over on the other end of the state.

North Carolina, that is. It’s a terrific location to set the stage for some fine detective work, but as fine as the camaraderie between Alex and the local townspeople is; as fascinating as the busted romances between Mor and Emma, and Alex and Elise, are; and watching them getting patched up again — or do they? — and as interesting as being shown the vicissitudes of running a modern-day hostelry establishment is, there’s not a heck of a lot of time left in not too many pages to solve a murder or two.

Emma’s ex is the first body to be found, followed by one of the two candidates for mayor of Elkton Falls, but the election must go on, and since it’s now a matter of husband running against wife (Tracy Shook vs. Connor Shook), the campaign is getting nastier and nastier, and that’s what’s on everyone’s mind.

Which is all well and good, but perhaps you know what I’m thinking, and you might be right. The solution to the murders boils down to (a) a slip of the tongue on the part of the guilty party, (b) a wild leap in logic on the part of Alex, and (c) an unconvincing change of character on the part of the party in part (a).

Nor is there anything fancy about Myers’ level of writing, pitched at, say, advanced middle school students. Which makes it sound terrible when it isn’t, but you shouldn’t read this book and expect to find much worth quoting to anyone sitting in the same room with you.

And the book is entertaining, don’t mistake me there either. It’s just that as a mystery, it has awfully weak legs.

— September 2003

The Alex Winston “Lighthouse Inn” series:

1. Innkeeping With Murder (2001) [Agatha Award nominee, Best First Novel]

2. Reservations for Murder (2002)

3. Murder Checks Inn (2003)

4. Room For Murder (2003)

5. Booked for Murder (2004)

6. Key to Murder (2010)

7. Ring for Murder (2011)

Tue 24 Jan 2012

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

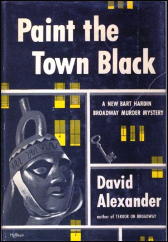

DAVID ALEXANDER – Paint the Town Black. Random House, hardcover, 1954. Bantam 1534, paperback, 1956.

Bart Hardin, managing editor of the Broadway Times, is in urgent need of $500. On the recommendation of an old friend, television commentator Mike Ainslie, he applies for a press-agent job with the Latin American Trade Alliance.

Hired for the position, Hardin returns to his apartment over Bromberg’s Flea Circus and finds Ainslie’s tortured body in front of his fireplace. Hardin’s problems are compounded by the fact that he must break the news to Ainslie’s wife, Dorothy, with whom he is in love.

The newspaperman’s personal involvement with both the murder and the trade alliance — which urgently wants to recover a fake pre-Columbian jug that Ainslie reportedly had in his possession prior to his death — leads him into encounters with a strange curio-shop owner, a psychologist who collects art, a strongman named Andes, and a chinless man with a penchant for sadism.

Hardin is an engaging character: a denizen of Broadway who sports embroidered vests and a cynicism that is undermined by his ability (which he would term a flaw) to care deeply — be it for a murdered friend or his old blind dog.

David Alexander’s portrayal of the people of Broadway gives full rein to their eccentricities, but stops short of being unbelievable. The plot is intricate, and all elements tie off neatly at the conclusion.

Other notable Bart Hardin titles are Terror on Broadway (1954), Die, Little Goose (1956), Shoot a Sitting Duck (1957), and Dead, Man, Dead (1959).

Alexander also created two other series of two books each. The first features the detective duo of Tommy Twotoes, an eccentric penguin fancier, and private eye Terry Rooke (Most Men Don’t Kill and Murder in Black and White, 1951); the second stars Broadway lawyer Marty Land, who also appears in the Hardin series (The Death of Daddy-O, 1960, and Bloodstain, 1961).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 24 Jan 2012

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller & Bill Pronzini

DAVID ALEXANDER – The Madhouse in Washington Square. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1958. Collier 113, paperback, 1961.

The Madhouse in Washington Square is a tavern frequented by a regular group of social misfits, one of whom is John Cossack, “a painter of barber poles … a barroom porter, a manufacturer of bombs, and something of a philosopher.”

It is Cossack who finds failed writer Carley Dane beaten to death in Dane’s Greenwich Village cold-water flat. Any number of people had reason to kill the despicable writer, including most of the habitues of the Madhouse.

Cossack doesn’t wish to see any of these people, his friends, behind bars. Besides, reporting the murder will interfere with preparations for his grand and compassionate scheme to blow up the tavern with one of his homemade bombs, thus putting its largely unhappy patrons — himself included — out of their collective misery.

As Cossack’s scheme unfolds (and as circumstances force him to reluctantly assume the role of sleuth), Alexander introduces the reader to each habitue: Manley Ferguson, a frustrated artist; Helen Landers, a model who, when in her cups, suffers an overwhelming urge to do an impromptu striptease; wasted Peter Dotter, once rich and now a hopeless and pitiful alcoholic; Major Trevor, eighty-year-old veteran of the Boer War and World War 1, who supports himself by playing small character roles on the stage and on television; bitter old Martha Appleby, whose driving force for close to twenty years has been her hatred of Carley Dane.

Other suspects include Bruno Madegliani, owner of the Madhouse, who loathes and mistrusts his customers and whose secret passion is to find the long-lost idol of his youth, a champion cyclist named the Great Goldoni; Penny Caldwell, a sensitive young poet who fancies herself another Emily Dickinson; and George Dabney Sturgis, a recently discharged soldier who came to New York just to meet Dane and received a rude welcome.

Events set in motion in each of these characters’ lives during this crucial day are neatly resolved in the final pages; and Cossack reveals the identity of Dane’s murderer. As for his bomb … well, you’ll have to read the novel to find out whether or not the climax is literally an explosive one.

In A Catalogue of Crime, Barzun and Taylor called The Madhouse in Washington Square “close to unreadable”; Barzun and Taylor obviously have no patience with eccentric prose styles and no empathy for eccentric characters.

The fact is, the novel is not only readable but quite moving, owing in large part to David Alexander’s ability to sympathetically portray individuals whose lives and actions are far beyond the limits of rational human behavior. His treatment of these misfits is compassionate and gently humorous — and Madhouse is a kind of poignant tribute to all misfits, everywhere.

Alexander’s other non-series novels are Murder Points a Finger (1953) and Pennies from Hell (1960). The latter, a tale of menace and persecution reminiscent of Hugo’s Les Miserables, is particularly good.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 22 Jan 2012

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

SALLY, IRENE AND MARY. MGM, 1925. Constance Bennett, Joan Crawford, Sally O’Neill, William Haines, Henry Kolker, Douglas Gilmore. Based on a play by Eddie Dowling. Director: Edmund Goulding. Shown at Cinecon 39, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2003.

I have fond, if vague, memories of the 1938 remake of this silent film that featured Alice Faye, Tony Martin, Fred Allen, Joan Davis, Jimmy Durante, and Gypsy Rose Lee (quite a cast!), but I had never seen the original film.

Constance Bennett (Sally), Joan Crawford (Irene), and Sally O’Neill (Mary) are showgirls, with Sally the older and wiser gal who’s seen it all but is happy with her older lover who keeps her in luxury, and Irene and Mary the recent recruits, childhood friends from the same tenement background.

The film alternates between the giddy, dangerous after hours parties and the tenement apartments where families fear they are losing their daughters to a sinful show business world. The adventure will end tragically for one of the tenement girls while the other will return to her childhood sweetheart.

The scenes in which the showgirls talk and gossip among themselves are striking in their mixture of dreams and occasional rueful incursions of reality. Crawford is the standout, although Bennett is almost as fine in her “mother hen” portrayal.

Sun 22 Jan 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

JEAN HAGER – The Grandfather Medicine. St. Martin’s Press, 1989. Worldwide Mystery, paperback, November 1990.

There is nothing like a murder to get your mind off your own troubles, and that is exactly how Buckskin’s Chief of Police Mitch Bushyhead feels when the body of full-blooded Joe Pigeon is found. Mitch’s wife has recently died, and he is still feeling the gap in his life, especially when it comes to raising their only daughter Emily without her.

Buckskin is in Oklahoma, by the way. While Bushyhead himself is only half-Cherokee, he was brought up by his white mother, and is far from being any kind of authority on Cherokee ceremonies and traditions. However, no one else knows of any reason why two fingers are missing from the dead man’s hand either.

On the face of it, this is a police procedural, but it’s one of the Bill Crider/Sheriff Dan Rhodes variety, in which the people in a small town quickly become long-time friends of the reader. And since the police force consists only of the Chief and a few well-chosen officers, a case of murder becomes essentially a one-man job, nothing at all like the cases that the 87th Precinct, for example, has to deal with.

If you gather I liked the book, you’d be right. I also thought the culture and background of the Nighthawk Keetoowahs, a secret society of a few full Cherokees, fighting for their identity in a white man’s world, was perfectly done. And last but not least, the mystery that has to be solved is wrapped as neatly as any I’ve read in the past few months.

In other words, here’s a book to be looking for.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 32, July 1991 (very slightly revised).

Editorial Comment: The Grandfather Medicine was Jean Hager’s first mystery novel. She was the author of three different series over her mystery-writing career; lists of all three can be found in my review of Sew Deadly (1998), in which Tess Darcy, a bed-and-breakfast owner, is the detective of record.

Fri 20 Jan 2012

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

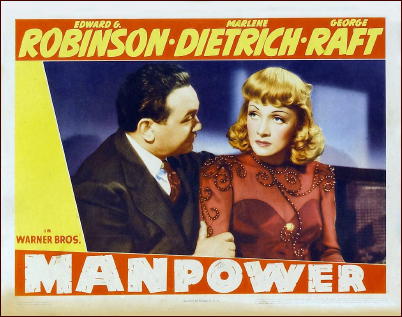

MANPOWER. Warner Brothers, 1941. Edward G. Robinson, Marlene Dietrich, George Raft, Alan Hale, Frank McHugh, Eve Arden, Barton MacLane, Ward Bond, Walter Catlett, Joyce Compton. Director: Raoul Walsh.

I’ve often said that Raoul Walsh and Michael Curtiz were the two most artistic directors ever to come out of Hollywood, and the next time someone doubts it, I’ll show them this film.

Back in the early 30s, Howard Hawks made a film called Tiger Shark, with Edward G. Robinson, Richard Arlen and Zita Johann, about two fishermen-buddies drawn to the same woman, and what happens when she marries the wrong one.

It made a lot of money for Warner Brothers, so the Studio Heads, with the wisdom of their breed, used to dust off the script, every other year or so, change the profession to Well Drilling, Stunt Flying or what-have-you, and make it again with a different cast and director. No wonder the Warners’ Script Department was known as Echo Valley!

By 1941, Edward G. Robinson had again rotated into the Chump role, with George Raft and Marlene Dietrich as his friends and lovers. The profession this time was Power Line Repairmen, and the director was Raoul Walsh.

The result is Hollywood Filmmaking at its Absolute Apex. The whole idea of making a film about a vast, outdoorsy job like Power Line Work entirely on Studio Sets seems audacious when you think about it, but it probably never occurred to Walsh or Warners to do it any other way.

The studio “exteriors” are beautifully constructed, and Walsh moves his craning camera through them with an easy grace that recalls the best of Fred Astaire.

He gets real excitement from shots of men clinging to icy towers, in no way diminished by their obvious fakiness, and he manages to break down George Raft’s usual reticence almost completely; there’s a strong sense of Feeling in the scenes between Raft and Robinson, and startling, genuine sexual tension between Raft and Dietrich.

Best of all, despite the fact that this plot had been done to death by the time he got to it, Walsh makes it seem almost spontaneous. As the characters move on their predestined routes towards Betrayal and Murder, there’s never the sense of Fatalism that could so easily suffuse a worn-out storyline like this.

Of course, Walsh does all this and a lot more with a quiet professionalism that entirely eludes most critics, but a careful look at his camerawork, pacing, and feel for the material show a director who deserves to be taken a lot more seriously than many of his better-known contemporaries. Maybe someday he will be.

— Reprinted from A Shropshire Sleuth #51, September 1991.

Fri 20 Jan 2012

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

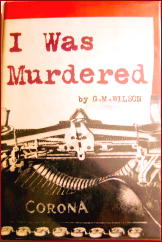

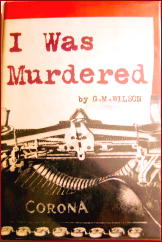

G. M. WILSON – I Was Murdered. Robert Hale, UK, hardcover. Walker, US, hardcover, 1961.

Unlike one person who shall remain nameless, I have no objection to the supernatural in mystery stories as long as the author presents the occult persuasively. Wilson’s spook fits that demand, even unto the spirit’s shedding of good sense along with the removal of its physical shell.

Miss Purdy, maiden lady in her mid-50s, has been writing detective stories for 30 years. Seeking an out-of-the-way country place in which to begin her new novel, she ends up at Waterside Cottage in Norfolk.

Unfortunately, it is already occupied — by the ghost of Lilian Kemp, seemingly accidentally drowned in Liddon broad behind the cottage. The ghost takes over Miss Purdy’s mind temporarily and dictates, “I was murdered.”

In her attempts to see that justice is done so that Kemp’s spirit may be put at rest, Miss Purdy stirs up things. Another drowning in the broad occurs, this time definitely murder.

While the haunt is persuasive, the author’s characterization of Miss Purdy won’t fool you: Miss Purdy has never written a detective story, nor seemingly read one. As proof, the murderer is evident to anyone with merely a minuscule knowledge of the genre, but Miss Purdy has no suspicions.

Worse, the murderer calls Miss Purdy and tells her that there has been a dramatic development in the case and that she should meet the caller at dead of night in a deserted spot without letting anyone know of the meeting. With no hesitation she proceeds to do so. Now, I ask you: Would that be the behavior of an experienced mystery novelist? That is to say, other than James Corbett?

Wilson, I gather, wrote additional novels with a supernatural background, most of them featuring Inspector Lovick, who stolidly does not believe in the occult and, since he also does not spot the murderer, is obviously inept.

While Wilson doesn’t construct a tenable plot, she does write well and holds one’s attention.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 4, Fall 1990.

Editorial Comments: (1) I do not know whom Bill was referring to in the first paragraph. It might have been any number of people at the time, including myself. I’m not as much of a purist as I used to be, but a lot of attempts to mix the paranormal with the detective story fall as flat to me as the proverbial flapjack.

(2) As Bill hints at and so stated by one blogger, G. M. Wilson may have been one of the first mystery writers to have combined the Mystery Story with Ghosts. Since her first book was published in 1948 (a non-Lovick), the claim seems unlikely, but if you’re so inclined, it does suggest her books may be worth tracking down.

(3) James Corbett was a particularly inept mystery writer whose work Bill was particularly fond of. But sentences like this one ought to be sign of genius, rather than a lack of skill with pen to paper, shouldn’t it? “She was visibly excited, yet not a vestige of her features betrayed her.” Follow this link for more of Deeck on Corbett.

(4) The author’s initials stood for the rather prosaic Gertrude Mary. I Was Murdered was the only one of her two dozen mysteries to be published in the US. Inspector Lovick appeared in 21 of them, and of those, Miss Purdy was on hand in twelve. Bill didn’t make much mention of Lovick, and then only disparagingly. Nonetheless, I’d like to try my hand at one, and if possible, sooner rather than later.

« Previous Page — Next Page »