January 2012

Monthly Archive

Thu 5 Jan 2012

1. INQUIRY: From Bill Pronzini: Just for the heck of it, here’s a quiz question for you and M*F readers: Can you name at least one mystery novel narrated by a chauffeur, or in which a chauffeur is the investigating detective? I can supply the title and author of one and am wondering if there are others.

2. A New OTR Website. It might not be correct to call the CBS RADIO MYSTERY THEATER “Old Time Radio,” but given that the program ran for eight years beginning in 1974, it means that it’s been nearly 30 years since its last broadcast. There is a website that not only lists all 1399 episodes, but it also includes cross-listings for all of the performers and writers. And not only that, you can download or listen to each and every one. How many months would that take, if you did it non-stop? Pull out your calculators! Check it out at http://www.cbsrmt.com/

3. Pulp fiction writer Charles Boeckman is 91 and no longer writing, but his jazz band is still going strong. Check out a photo gallery of his latest gig here.

4. Headline in a local paper: Police were called to a day care center where a three-year-old was resisting a rest.

UPDATE. 01-06-12. My description of Charles Boeckman as a pulp fiction writer was challenged on a Yahoo group where I also posted the link to the photo gallery above. I was advised that Boeckman was a writer of hard-boiled fiction but not published in pulp magazines.

I shouldn’t have been so short and brief in my post there, nor in the one above. I should (and could) have supplied more of a résumé for Boeckman, and I’m sorry I didn’t.

It was Walker Martin who came to my rescue on that Yahoo list, and I hope he doesn’t mind my repeating some of the credentials for Boeckman I should have provided:

“Charles Boeckman under the name Charles A. Beckman started writing for the Popular Publication line of pulps in the late 1940’s and continued until the pulps bit the dust. Such titles as Fifteen Western Tales and Detective Tales carried much of his short fiction. He also made the switch to the digests. I recently noticed his name in Manhunt.”

Boeckman is one of the very few authors who wrote for the pulps still living — a survivor — and he should be recognized as such. I’m wondering whether he might be a suitable guest for one of the two annual pulp conventions sometime soon. Playing in a jazz band at the age of 91 seems to suggest that his health may be good enough to attend.

Thu 5 Jan 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

As a novice widower I find myself thinking of three other mystery writers who lost wives to Mister Death. The first name that springs to mind in this connection is Raymond Chandler (1888-1959), who was so devastated by the death of his wife Cissie that he tried to shoot himself in his bathroom.

Being blind drunk at the time, he missed his target. “She was the music heard faintly at the edge of sound…†he said of Cissie. “She was the light of my life, my whole ambition. Anything else I did was just the fire for her to warm her hands at.â€

Next comes Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), whom I never met but have been associated with for most of my life. He married the former Hazel Goodwin in 1919 and they were together until she died of cancer in May 1960.

During the months of her final illness and after her death he was unable to write fiction, but he continued sending out his off-the-wall “Walter Keyhole†newsletters to just about everyone whose address he had.

He called them polychromatic or multitinctorial cartularies since each page was printed on paper of a different color. We who have lived into the computer age recognize them as the functional equivalent of a blog. It cost him as much as $50 to have each installment prepared by a professional typing service and mailed out en masse.

I have originals or photocopies of 188 of these, which a few years ago I organized and offered to a panting public as The Keeler Keyhole Companion (2005). Among the hundreds of topics he touched on was his life as a lonely widower in his early seventies, “a guy who lives on canned Campbell’s soups and canned Sultana pork and beans.â€

Here’s his account of the “long lonely Thanksgiving holiday†in 1962. “We [he often uses the royal we in these cartularies] had our choice of having 3 soft-boiled eggs (only thing we can cook) as a dinner, then seeing the Three Stooges conk each other over the heads [at the local movie house], or of having 3 soft-boiled eggs as a dinner and re-reading Keyser’s Mathematical Philosophy. You guess!â€

I now feel closer to that genuine mad genius than ever before. He was only a year or two older at his wife’s death than I at Patty’s. He sold the old house they had lived in for decades and moved into an apartment hotel, while I’ve recently bought a condo and put my own Toad Hall on the market. I’m no better at cheffery than Harry was but have the advantage of living in the age of that fantastic contraption known as the microwave.

The third author in whose moccasins I now walk became a widower not once but twice. Fred Dannay (1905-1982), better known as Ellery Queen, married the former Mary Beck in 1926. She died of cancer on July 4, 1945, leaving Fred with two small children to raise.

In 1947 he married the former Hilda Wiesenthal, who was ten or eleven years younger than he and was the daughter of a cousin of Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. She died in 1972, also of cancer.

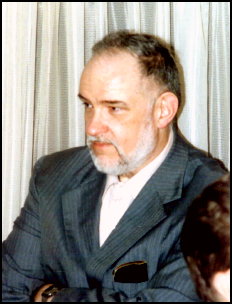

By that time I had come to know Fred well and he had become the closest thing to a grandfather I had ever known. I went through this awful period of his life with him. There’s a photograph of him taken at this time which shows the empty devastated face of a man waiting for the dark to claim him.

Just as Keeler had married again a few years after Hazel’s death, so did Fred a few years after Hilda’s. I got to know Thelma Keeler well and am convinced that she saved her husband’s life. I also have no doubt that Fred’s third marriage, to the former Rose Koppel, saved his. Will I luck out in my final years as they did?

I apologize for devoting so much of this column to death but I really don’t have much choice at the moment. Less than a week before Christmas I learned that I’d lost one of my closest mystery-loving friends.

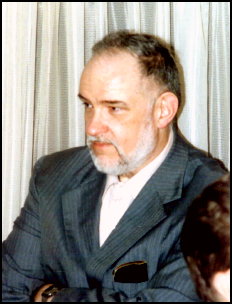

Bob Briney was something of a universal genius. Physically he evoked Orson Welles or Nero Wolfe but was soft-spoken and totally without their irascibility and moved with a certain gingerliness as if he were afraid he’d crush something if his movements were more forceful.

He was born near Benton Harbor, Michigan in December 1933 and spent most of his academic career in Massachusetts, at Salem State University. He earned a Ph.D. in mathematics and recovered from the ordeals of his dissertation and orals, so he told me, by reading most of the novels of John Dickson Carr in less than a month.

Like the clever men of Oxford in The Wind in the Willows, he “knew all that was to be knowed‗about mystery fiction, fantasy, s-f, horror, Westerns, just about every form of popular fiction you can name, plus ballet and opera and movies and classical music and so much more.

His ability to keep prodigious masses of data in perfectly organized form would have shamed many a computer. He wrote prolifically and with dry wit about books and authors, assiduously collected works in the genres he loved — every room in his large house including the bathroom was a library first and foremost — and corresponded with Sax Rohmer, P.G. Wodehouse, John Creasey and countless other authors.

It was pure pleasure to read his commentary or listen to his conversation. We started corresponding in the late Sixties, thanks mainly to Al Hubin and The Armchair Detective, and met for the first time in 1970 when I took a bus from New Jersey to a science fiction convention in Manhattan that he was attending.

Beginning in 1980 he followed in Keeler’s footsteps by putting out the pre-computer equivalent of a blog, which he called Contact Is Not a Verb (a famous line from one of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novels) and kept going until September 2006, a grand total of 149 issues, of a copy of every one of which I am a proud possessor.

Bob developed diabetes and in the fall of 1990, when I was a visiting professor in New Jersey, had to have some of his toes amputated. Unable to climb the stairs of his own house, he was sleeping in a hospital bed installed on the ground floor. I traveled to Salem by Amtrak and spent a long weekend playing housekeeper: schlepping cartons around so he could access the classical music he loved, taking his clothes to the laundry, even cooking us a few meals (for whose quality I will not vouch).

Until a few years ago we would rendezvous every summer at the Pulpcon in Dayton, Ohio. Then unaccountably this shy but gregarious man dropped out of sight. Almost no one heard a word from him or knew anything about his health.

Finally, just a few days before Christmas, I learned he’d been found dead in his house late in November. He had no immediate family. As of this writing I don’t know the cause, or what will happen to the vast library he had accumulated over the decades. All I know is that he was one of the most brilliant and memorable people in my life.

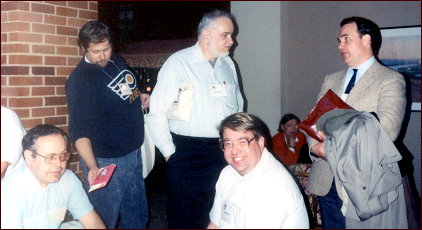

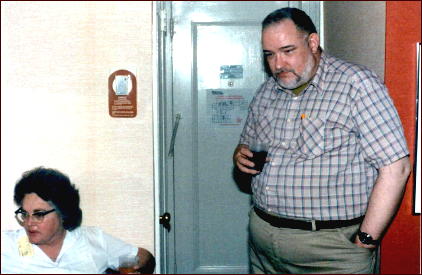

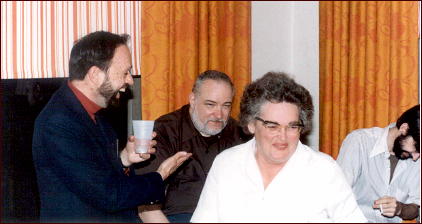

Bouchercon, Philadelphia, 1989. Me (Steve Lewis), Art Scott, Bob Briney, George Kelley, and Mike Nevins. Photo taken by Ellen Nehr.

Bouchercon, New York, 1983. Ellen Nehr and Bob Briney.

Bouchercon, Chicago, 1984. Marv Lachman, Bob Briney, Ellen Nehr and Steve Stilwell.

Many thanks to Art Scott for providing the photos above.

Wed 4 Jan 2012

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

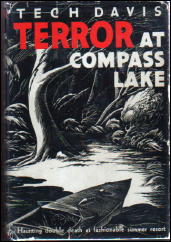

TECH DAVIS – Terror at Compass Lake. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1935.

Occasionally when I am on the fringes of a group of diehard mystery fans — which is about as close as they’ll let me get — the name Tech Davis is mentioned. Then when I am spotted, the subject is immediately changed.

Why this happens I do not know. Oh, I know why I’m allowed only on the fringes; it’s their not wanting me to hear about Davis that baffles me. While Davis is not a good author; he isn’t an exceptionally bad one.

His prose doesn’t elevate, indeed may be said to enervate. His detective, Aubrey Nash, is so bland that I wish he’d been given the one or two idiosyncrasies that I usually deplore in other fictional detectives whose creators can’t seem to make come alive. But he does plot well.

In this novel, the first of three by Davis, Aubrey Nash is asked to come to the wilds of upstate New York to investigate the apparent suicide of a chauffeur — it must be suicide since everyone has a perfect alibi — and the later stabbing death of his employer in a locked room. Nash isn’t interested until he receives a telegram telling him the crime is insoluble and he shouldn’t waste his time with it.

Recommended for locked-room fanciers, and other problem solvers.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 4, Fall 1990.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Mystery fiction by TECH DAVIS, pen name of Edgar Davis (1890-1974). Series character: Aubrey Nash in all.

Terror at Compass Lake. Doubleday, 1935.

Full Fare for a Corpse. Doubleday, 1937.

Murder on Alternate Tuesdays. Doubleday, 1938.

Editorial Comment: Just in case anyone is tempted by Bill’s last line into putting together a complete set of all three Tech Davis mysteries, there are five copies of his books currently listed on ABE. Four of them are of Compass Lake, available at $75 and up, and there’s one of Full Fare, the latter having an asking price of a fairly solid $250.

And not a single copy of Alternate Tuesdays.

UPDATE. 01-08-12. Thanks to Bill Pronzini, I can now show you cover images for all three Tech Davis mysteries, in jacket.

Wed 4 Jan 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

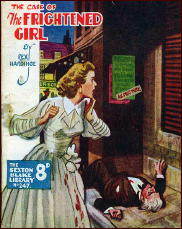

REX HARDINGE – The Case of the Frightened Girl. Sexton Blake Library #247. Paperback original. [Amalgamated Press, UK, 3rd series, September 1951.]

The basic premise of this short novel, 64 pages of small type in a double-column format, was promising – in fact, more than promising, if “impossible crimes†are meat if not potatoes in your regular diet of detective fiction reading.

The girl in the title is Moira Leonard, a girl with a fabulous singing voice, but with a overbearing Svengali of a manager and singing instructor. After her public vocal debut, she cracks under the strain she’s been under and flees the music hall. Max Rosen follows her, argues with her, and ends up dead, stabbed in the back, with plenty of witnesses to say there she was the only one near their final (and fatal) confrontation.

But when the body is examined there is no murder weapon to be found. The girl must have done it and taken the knife with her. Sexton Blake does not believe she did the deed, however, nor does his young assistant Tinker, especially the latter, even though she has disappeared, and into literal thin air.

This takes us through the first eight or nine pages. We also learn that Ron Pearce, a would-be lover of Moira – they grew up together in the same orphanage – would have also had a motive, but the absence of the weapon clears him.

So as I say, a promising premise, but once we learn that Pearce is the one responsible for kidnapping Moira, there is little more I need to tell you about the story.

Rather than a detective story – until the end when the “how†is revealed – this is a thriller novel, and not a very good one. There is too much padding, too much recapitulation of the plot, and too much chase and too little suspense to give me little reason to recommend this to you, unless you’re curious about knowing what a Sexton Blake novel was like in the early 1950s. Or at least what this one was like, as I was.

And oh, as for the “impossible crime†aspect? Totally mundane and not very believable at that. [See Comment #1 for more!]

Tue 3 Jan 2012

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

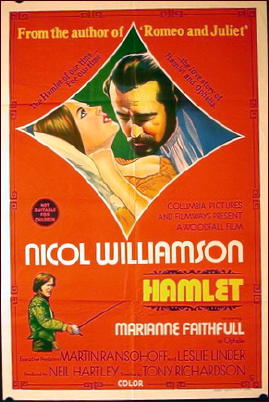

HAMLET. Columbia, 1969. Nicol Williamson (Hamlet), Judy Parfitt (Gertrude), Anthony Hopkins (Claudius), Marianne Faithfull (Ophelia), Mark Dignam, Michael Pennington, Gordon Jackson, Ben Aris, Clive Graham. Based on the play by William Shakespeare. Director: Tony Richardson.

I also recently saw Nicol Williamson’s 1969 film of Hamlet, directed by Tony Richardson, made on the heels of Zeffirelli’s surprise Romeo & Juliet hit. Didn’t care much for it, but I was prejudiced two-score years ago by the film’s banal ad campaign, which billed it as “The story of Hamlet’s immortal love for Ophelia!”

Now Hamlet is about a lot of things, but it ain’t about Hamlet’s love for Ophelia, and this slant on the film, intentional or not, put me off on it right from the outset, no doubt clouding my judgement somewhat.

Williamson plays Hamlet as a bookish Grad Student, Weak rather than Vulnerable and Pedantic instead of Poetic. It’s a valid interpretation, but not much fun to watch for two hours.

Likewise Judy Parfitt’s portrayal of Queen Gertrude as Lady MacBeth. Marianne Faithfull is okay as Ophelia, but an incredibly young Anthony Hopkins, looking like a kid in a false beard, is woefully out of his depth as the King.

This is very much a late-60s film, with the kids in revolt against corrupt and complacent authority figures, which again is a valid interpretation, but robs the play of some of the depth and complexity it gets when characters like Polonious, Claudius and Gertrude are developed as rounded characters.

Finally, there are no sets to speak of (this looks to have been shot in the back of UCLA’s Theatre Department Building) and Richardson tries hard to hide this by concentrating on close-ups and restricting physical movement, which works but stifles the action.

— Reprinted from A Shropshire Sleuth #52, March 1992.

Mon 2 Jan 2012

A THREE STOOGES Movie Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“Punchy Cowpunchers” (1950). A Three Stooges short. Running time: 17 minutes. Shemp Howard, Larry Fine, Moe Howard, Jock O’Mahoney (Elmer), Christine McIntyre (Nell), Kenneth MacDonald (Dillon), Dick Wessel (Mullins), Vernon Dent (Colonel), Emil Sitka (Daley), George Chesebro (Jeff, uncredited). Written and directed by Edward Bernds.

The Three Stooges are definitely not for all tastes, so if you don’t like slapstick comedy just skip this review.

“Punchy Cowpunchers†spoofs just about every cliche hitherto found in Western films: the outlaw gang looting the town; the stalwart, jut-jawed, guitar-playing, “aw shucks!” hero; the virginal love interest for the hero; and the U.S. Cavalry ready to ride in on a moment’s notice and save the day.

Only the outlaws (“The Killer Dillons”) aren’t too bright — and neither is our hero (Elmer), a total klutz who can’t stay on his horse, constantly collides with objects and people (“I hurt mah knee agin”), forgets to load his guns (and when he does remember can’t shoot straight), and, let’s face it, doesn’t play his “geetar” very well.

As for his “gal” (“Nell honey”), she’s far from being the “poor, defenseless woman” she claims to be. When one gang member after another tries to kidnap her (for nefarious purposes, no doubt), she decks them all and then each time demurely passes out — but not until she’s found something soft to land on.

And forget the cavalry — they just got paid, and as the colonel says, “Well, you know, boys will be boys.”

“Punchy Cowpunchers†takes the best of Stooges slapstick and distills it into less than twenty minutes of fast-paced nonsense. The only other short feature I really liked from these guys was “Dutiful But Dumb” (1941), a political satire featuring Curly’s epic battle with his supper, a bowl of chowder inhabited by a very rude clam (a masterpiece of timing and film editing).

The klutzy “hero” was played by Jock Mahoney (1919-89), a former stunt man double for Errol Flynn, Gregory Peck, and John Wayne. Mahoney went on to appear many times in films and TV, including 77 episodes of The Range Rider (1951-53), 34 episodes as Yancy Derringer (1958-59), and several appearances in Tarzan films, sometimes as the villain and sometimes as the vine swinger himself. For a more intellectual Mahoney, see the sci-fi snoozer The Land Unknown (1957).

“Nell honey” was played by Christine McIntyre (1911-84), who possessed an operatic-level singing voice (not employed in “Punchy Cowpunchersâ€). She spent most of her film career working in short features, many of them with The Three Stooges. She even appeared several times in Mahoney’s Western series, The Range Rider.

Kenneth MacDonald (1901-72) frequently showed up in Stooges shorts as a bad guy. He went on to play the judge 32 times in the Perry Mason series, starting with the second show and finishing up with the very last episode.

Mention should also be made of George Chesebro (1888-1959), whose film career started in 1915. Chesebro often appeared as a henchman (usually the third one through the door) or a cop. The IMDb credits him with over 400 titles.

You can watch “Punchy Cowpunchers“ in two segments on YouTube: Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

Sun 1 Jan 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

WILLIAM CAMPBELL GAULT – Night Lady. Crest 260, paperback original, 1958. T.V.Boardman, UK, hardcover, American Bloodhound Mystery #307, 1960. Never reprinted in the US.

William Campbell Gault got his start writing for the pulp magazines, beginning around 1940, maybe earlier, producing not only mystery stories and crime fiction, but doing a slew of sports stories as well. When the pulps faded away and paperbacks came along, he, as did many others, went with the flow. His first Joe Puma novel, Shakedown, was written under the name of Roney Scott as half an Ace Double in 1953.

Then after a short hiatus came five Puma adventures in three years from Crest, then a hardcover novel, The Hundred-Dollar Girl, from Dutton in 1961. Gault switched to writing boys’ adventure fiction after that, and Joe Puma disappeared until The Cana Diversion was published in 1980 – about which more in a moment.

In many ways Joe Puma is your standard medium-boiled kind of private eye. His bailiwick is Los Angeles and immediate environs, mostly the seedier side of town, mixing it up with former small-time hoods, chiselers, grifters and big-time mobsters, along with a wide assortment of women. Night Lady is Puma’s third appearance, and while I can recommend it to almost any devout fan of private eye fiction, I have some serious reservations about it, and it’s highly unlikely that any publisher would consider reprinting it today.

I may totally wrong about this, but in terms of his writing, Gault seems to have been somewhat of a maverick, refusing to go along with the conventional, and veering off on occasion into strange, unusual ground.

Take the following excerpt from the first couple of paragraphs from Night Lady, as a mild example. As any good pulp writer should know, the first few lines are the most crucial in sucking the reader into the story. They have to be good, clear, and picturesque. Not this time. Here’s Gault’s take on professional wrestling and the wrestlers themselves:

It’s a trade that appeal [sic] to the narcissist. And from self-admiration it’s only a step to love of like for like.

And love of like for like can lead a man into something as socially responsible as Rotary or something as socially repugnant as homosexuality.

What is “love of like for like� It stumped me the first time I read it, and the second and third time, too. The words were there, but they didn’t make sense.

You’re probably way ahead of me in knowing what Gault was saying, but to me, it was like running a race with hurdles, and suddenly the hurdles are too close together, you trip, and you knock down the next one, and suddenly you’re cartwheeling down the track, arms and legs swinging out in all different directions, thud, thud, thud – and it stopped me cold.

And at the least, I wasn’t expecting this particular variety of deeply felt philosophy (page 23) to be expressed so abruptly and succinctly, not in the first paragraph. It caught me by surprise. I wasn’t an English major in college, and I avoided all of the English courses that I could, so don’t give me a letter grade on any of what I’m saying, but in any case, I think I flunked the first page.

You’ve also noticed the reference to homosexuality. In terms of either political correctness or just plain good taste, there are some references to gays in this book that probably would cause some fuss if they appeared in most fiction today: lavender lads (page 9), weirdies (page 11), a pansy bed (page 14), homo (page 29) and the old stand-by, queer (page 49). The word “gay†itself is not used.

Sometimes it’s Puma talking, sometimes it’s the people he’s talking to, without any particular rancor, other than the choice of words, but they’re there and they can’t be ignored. Someone else will have to finish this doctoral dissertation from this observation onward, however, not me.

You’re still waiting for me to say more about The Cana Diversion, perhaps. I haven’t forgotten, but let me first take care of those people who want to know more about the case Puma is working on in this book. He’s hired by a successful show-business wrestler named Adonis Devine to find his business manager, who’s been missing for two days. The business manager, male, also lives with Adonis, which means calling in the police may cause some problems.

When the missing man is found dead, the police do have to be called in, but since Puma does his best to stay on the good side of the law, he not only manages to keep a lid on things best kept hushed up, but he’s allowed to keep working on the case.

Which he does, and not only that, he obtains a new client, a rich girl who Puma thinks is seriously slumming, given her previous relationship to the dead man, his connection with the crooked (well, fake) wrestling entertainment business, and his “double-gaited†life style.

There is another girl involved as well, an eye witness to the killer’s departure, who is nice and who naturally needs Joe Puma’s protection. He’s kind of prickly about it, though. He’s a very class-conscious sort of individual. The women in this case, especially his new client and her friends, are high class group of people. Joe is lower middle class, and he quietly resents it. There is a chip on his shoulder throughout the book, not a nasty one, but a noticeable one.

Unusual. It gives the story some oomph that lesser accomplished private eye writers wouldn’t include, an edge that Gault has that other authors don’t. As for the mystery itself, Puma does a lot of detective work, but on page 128, with less than 30 to go, he himself has to admit that he has no more leads to follow or suspects to interrogate.

Then with some inspired guesswork and a curious slip on the part of the killer – there’s little the armchair detective at home could do to contribute – the case is solved, with still almost ten pages to go.

More of Gault’s maverick writing nature at work. Instead of cleaning up the loose ends, as he easily could have, Puma takes the time instead to fight a grudge match with his original client, Adonis Devine, the wrestler. Over five pages worth.

He also ends up in bed, just before that, with one of the two women in the case. I leave it to you to decide which one, or read the book for yourself. Given the caveats I’ve already expressed, Gault was a writer who always had something to say, and here as well, he’s definitely worth reading.

Now. If you’ve never read The Cana Diversion, and you think you might want to, you might also want to stop here. It’s common knowledge, though, so it’s not as though I’m releasing the Pentagon papers.

Gault’s other private eye detective was Brock “The Rock†Callahan, and when Gault starting writing mysteries again in the 1980s, he brought them together in the same book, The Cana Diversion.

Unfortunately, what he did was make Puma the murder victim, leaving Callahan the task of tracking down his killer. No other author has ever done this, before or since. I don’t know about you, but the idea has always seemed awfully creepy to me, and I’ve never read the book. (That’s a purely personal reaction, and if I were to try to explain further, it would probably tell you more about me than either you or I would want to know.)

And I realize, of course, that this leaves me open to widescale expressions of surprise and disdain, if not derison and dismay. In 1983 The Cana Diversion did nothing less than win the Private Eye Writers of America award for the Best Paperback Original of the Year. Sometimes it pays to go your own way.

Note: Thanks to Bill Crider, Richard Moore and Bill Pronzini for some insightful commentary they made on some preliminary versions of this review. The opinions as expressed above, however, remain as always, mine alone.

Sun 1 Jan 2012

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE TURMOIL. Universal-Jewel, 1924. Emmett Corrigan, George Hackathorne, Edward Hearn, Theodore von Fitz, Eileen Percy, Pauline Garon, Eleanor Boardman, Winter Hall. Based on the novel (1915) by Booth Tarkington. Director: Hobart Henley. Shown at Cinecon 39, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2003.

It’s probably difficult to appreciate the appeal Booth Tarkington had for earlier generations (which include mine). He’s probably best remembered as the novelist who provided the inspiration for Welles’ Magnificent Ambersons, but even earlier I read and reread his Penrod series, the story of an imaginative, adventuresome boy who did all the things that I, a dull, unimaginative, tradition-bound kid, never dared to do.

The Turmoil, however, is more in the vein of the Ambersons and is the story of a successful father who tries to direct the lives of his three sons, with disastrous results for two of them.

It’s a dark film that lacks the kind of riveting detail that a William deMille might have brought to it, but somehow manages to focus poignantly on the difficult road to manhood travelled by the third son, with a particularly fine performance by Eleanor Boardman as the young woman whose love he eventually returns.

NOTE: The cover shown is that of the Grosset & Dunlap “Photoplay” edition, 1924.

Sun 1 Jan 2012

MIGNON G. EBERHART – Murder in Waltz Time. Short novel; first published in The American Magazine, May 1953.

This small gem of a detective story was reprinted in two of Mignon Eberhart’s later story collections, Deadly Is the Diamond (Random House, hc, 1958) and Best Mystery Stories (Warner, pb, 1988), and calling it a “short novel” is stretching it a bit, at best. Without resorting to counting words, I’d say it would run 60 to 100 pages in an ordinary paperback, depending on the size of type.

As I’m sure you know, many of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe tales first appeared in this same format and in this same magazine and were collected later in hardcover in groupings of three or four.

The American Magazine was always a favorite of mine as a youngster. I liked the cartoons, the photos, and the ads. Today I’m attracted to the same things, but now I like the stories and the artwork as well, plus the tidbits of interest about the movies, and items worth noting about radio and television stars and programs.

As for Eberhart’s story, it’s a solid detective tale, necessarily boiled down to its pure essentials because of its length. No time for but the briefest characterization, and the motivations barely more. It takes place in a Florida resort where the dancing team of Fran Allen and Steve Greene are the featured attraction, and it’s Fran who finds the body of elderly Miss Flora Halsey.

And as the investigation goes on, besides her nephew who was staying with her, more and more of the guests staying at the Montego House are found to have known Miss Halsey in the past, making Captain Scott’s job all the more difficult.

Here’s a paragraph that appears toward the end of the tale. It doesn’t reveal the killer in any way, but *WARNING* it might tell you more of the plot that you’d rather know, but I think it’s entirely indicative of the kind of story it is.

“Oh, yes, you know about that. Well, Scott’s men had picked up Jenkins at a bus stop. Abernathy recognized him; he’s the steward, all right. Abernathy had been trying to find Henry; he thought Henry was asking for murder, blackmailing the Senator, intending to use Abernathy as a threat, a witness, and put the screws on. Abernathy was too late; Henry had already acted and was murdered. We’ve told them about the Barselius. Bude admits to the lifeboat affair. Admits his sister knew about Henry’s attempts to blackmail him. Admits he had a gun. They can’t find the gun, and he admits his sister may have taken it, but — What’s the matter?”

“Nothing — nothing. Go on.”

Don’t get me wrong. As a mystery writer, Eberhart was a pro, through and through, and while I feel I might be admitting something you may find a little strange, I found this story to be much, much more than minimally entertaining.

AND IN THE SAME ISSUE:

FRANCES MALM – The Woman Involved. Short novel; first published in The American Magazine, May 1953.

There is no mention of Frances Malm in the current edition of Hubin’s bibliography of crime fiction, so unless she wrote tons of short fiction, I doubt that many readers today have ever heard of her. But since there’s more than one crime involved in this novella (my description) I’m reporting on it anyway — as I’m sure you’ve already noticed.

In length “The Woman Involved” is somewhat longer than the one by Mignon Eberhart, or at least that’s my impression. Once again I didn’t count words.

When a young woman, Dana Wallace, goes back home to settle her stepfather’s estate she finds, unexpectedly, both a mystery and a romance. A large sum of money is missing from Judge Poole’s checking account, and (with no apparent connection) a brash young man, on his way up and resented by the old guard residents of Middleford for doing so, offers to buy the property where the judge’s home is located.

Dana does a more-than-decent job of detective work, discovering a number things she did not know about her stepfather, but the emphasis here is rather more with the battle of rich vs. poor in matters of status in small town America, and Frances Malm puts her finger precisely on a number of the sore spots that can arise as a result.

A minor work, I’d have to truthfully say, and one that in all likelihood has never been reprinted. There’s no doubt that it’s mystery fiction, though, and it’s definitely worth reading.

PostScript. Frances had a sister named Dorothea Malm, who wrote a handful of novels published as gothic romance mysteries in the 1960s.

The only “real” novel that Frances wrote that I’ve been able to uncover is World Cruise (Doubleday, hardcover, 1960; Cardinal, paperback, 1961). Here’s the cover description of the book, the Cardinal edition: “The compelling story of a beautiful divorcee seeking love and fulfillment on a luxury cruise.”

— September 2003.

UPDATE. 01-01-12. My copy of this magazine has gone into hiding, and I’ve not been able to come up with a cover image, much less any of the interior art. Doing a Google search online, I did find a long partial description of the contents, however:

The American Magazine, May 1953. Vol CIV, No. 5. 144 pages. COVER: What’s Ahead for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor? Painting by Al Brule Articles include: AMERICA’S GLAMOROUS GODMOTHER Oveta Culp Hobby — the little woman who holds one of the biggest jobs in the US. A determined Texan, she looks out for the personal health and welfare of every one of us as US Secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. by Clarence Woodbury; COVER ARTICLE: What’s Ahead for the Windsors? The Coronation next month may mean a new career for England’s jobless ex-King. By Roul Tunley. 5 page article; FUN TIME IN THE ROCKIES Canada beckons summer vacationists to its fabulous wonderland. By Richard Neuberg; A PEEK AT THE MOVIES of the MONTH; “Nature Girl” a short story by Elizabeth Stowe; “The Lie” a short story by Cynthia Hope and Frances Ancker; “Murder in Waltz Time” by Mignon G. Eberhart.

Or in other words, a small time capsule of what life was like in May, 1953.

« Previous Page